14.7 Consequences of Altering DNA: Mutations

Hannah Nelson and Elizabeth Dahlhoff

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Identify the different types of mutations that can occur within genes.

- Explain how mutations in DNA alter (or do not alter) protein structure and function.

- Describe how a single base-pair mutation can radically affect the health of a person (sickle cell anemia).

Gene Mutations

A gene mutation is a permanent change in the coding region of DNA sequence of an organism. This alteration can occur spontaneously due to errors during DNA replication or be induced by external factors like radiation or chemicals (mutagens). Mutations are the raw material for evolution, as they introduce new genetic variations into a population. Gene mutations have varying effects on health, depending on where they occur and whether they alter the function of essential proteins.

DNA sequences in the coding region of a gene can be altered in a number of ways. The types of mutations include the following:

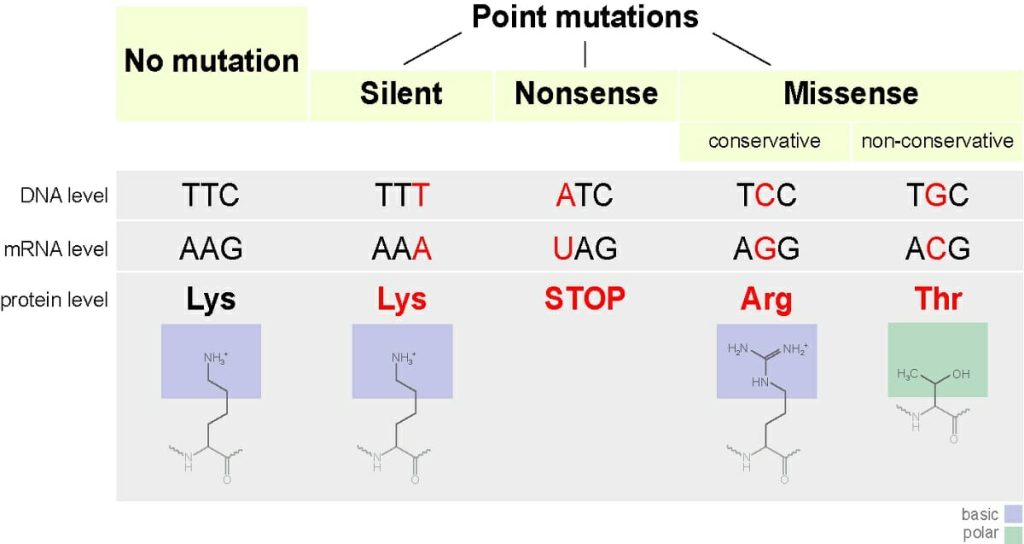

- Silent mutation: Silent mutations cause a change in the sequence of bases in a DNA molecule, but do not result in a change in the amino acid sequence of a protein (Figure 14.7.1).

- Missense mutation: This type of mutation is a change in one DNA base pair that results in the substitution of one amino acid for another in the protein made by a gene (Figure 14.7.1).

- Nonsense mutation: A nonsense mutation is also a change in one DNA base pair. Instead of substituting one amino acid for another, however, the altered DNA sequence prematurely signals the cell to stop building a protein (Figure 14.7.1). This type of mutation results in a shortened protein that may function improperly or not at all.

- Insertion or deletion: An insertion changes the number of DNA bases in a gene by adding a piece of DNA. A deletion removes a piece of DNA. Insertions or deletions may be small (one or a few base pairs within a gene) or large (an entire gene, several genes, or a large section of a chromosome). In any of these cases, the protein made by the gene may not function properly.

- Duplication: A duplication consists of a piece of DNA that is abnormally copied one or more times. This type of mutation may alter the function of the resulting protein.

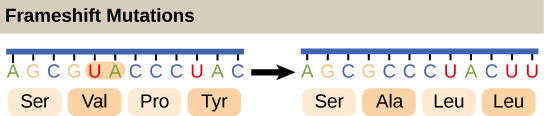

- Frameshift mutation: This type of mutation occurs when the addition or loss of DNA bases changes a gene’s reading frame. A reading frame consists of groups of 3 bases that each code for one amino acid. A frameshift mutation shifts the grouping of these bases and changes the code for amino acids. The resulting protein is usually nonfunctional. Insertions, deletions, and duplications can all be frameshift mutations.

- Repeat expansion: Nucleotide repeats are short DNA sequences that are repeated a number of times in a row. For example, a trinucleotide repeat is made up of 3-base-pair sequences, and a tetranucleotide repeat is made up of 4-base-pair sequences. A repeat expansion is a mutation that increases the number of times that the short DNA sequence is repeated. This type of mutation can cause the resulting protein to function in a completely different way than it would have originally.

Chromosomal Mutations

Chromosomal mutations are those that involve larger changes in chromosome structure. They include: deletions, where a portion of a chromosome is removed; Duplications, where a segment of a chromosome is copied, resulting in extra copies of genes; Inversions, in which a segment of a chromosome is reversed and reinserted; and translocations, where a segment of a chromosome is moved to a different chromosome.

Here is a summary video from the Amoeba sisters about gene and chromosomal mutations.

Video 14.7.1. Mutations (Updated) by Amoeba Sisters

Case Study in Mutations: Sickle Cell Anemia

Sickle cell anemia is a well-known example of a disease caused by a genetic mutation. It affects around 8 million people globally. The disease results from a missense mutation in the HBB gene, which encodes beta globin, a subunit of the hemoglobin protein responsible for carrying oxygen in red blood cells.

In individuals with sickle cell disease, the codon GAG (coding for glutamic acid) is mutated to GTG, which codes for valine. This single amino acid substitution, glutamic acid (a negatively charged, hydrophilic residue) replaced by valine (a non-polar, hydrophobic residue), significantly alters the folding of the hemoglobin protein in the aqueous cellular environment.

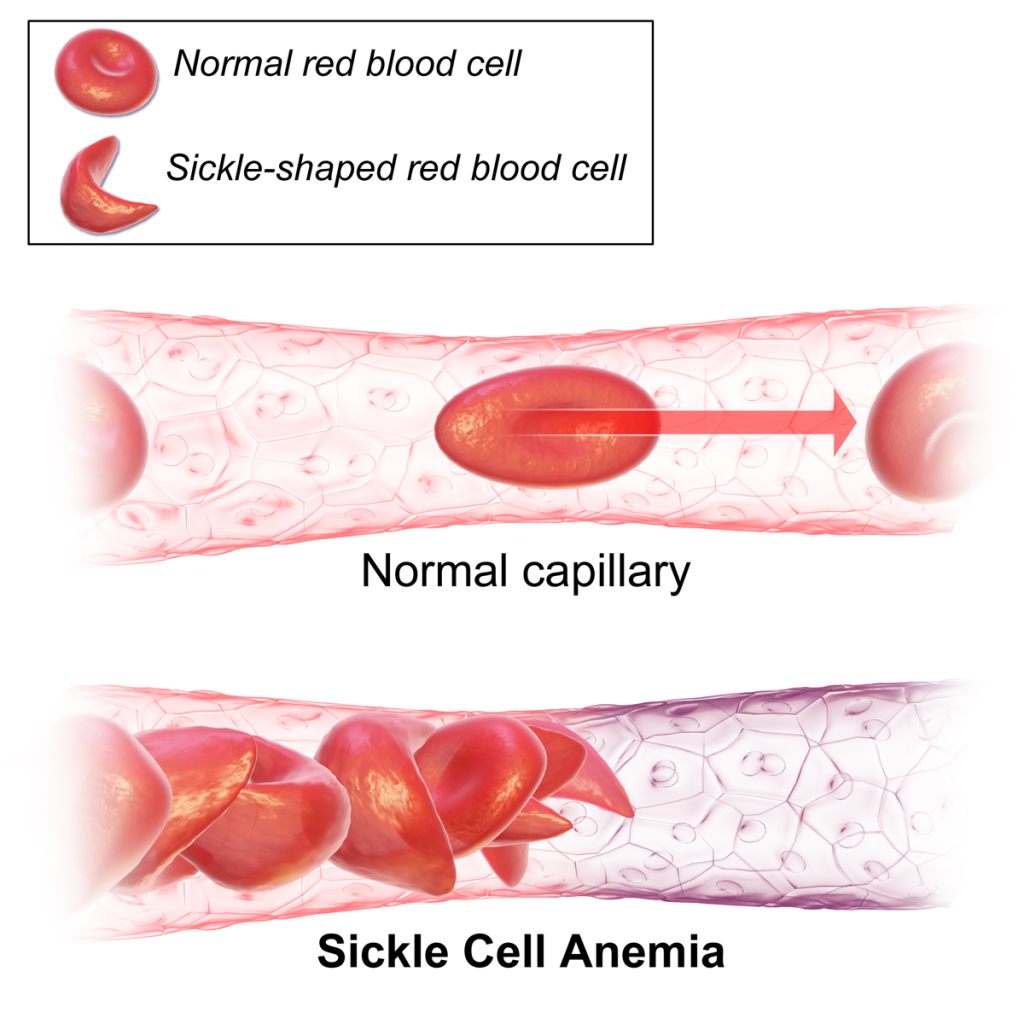

As a result, affected red blood cells adopt a crescent or “sickle” shape rather than the typical round form. These misshapen cells are more rigid and sticky, contributing to blockages in small blood vessels. This can lead to painful episodes, organ damage, and other serious complications due to restricted blood flow.

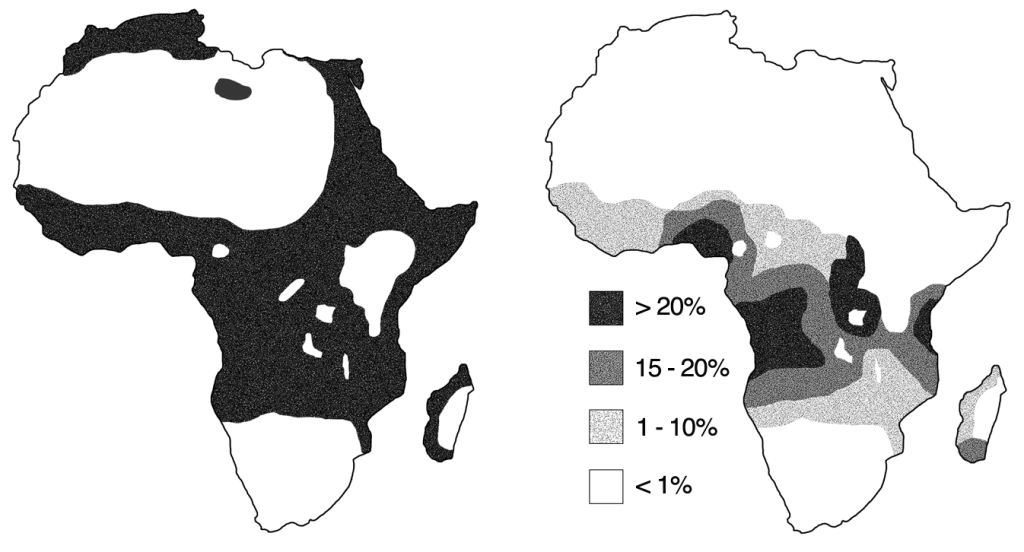

Sickle cell anemia is a genetic disorder, coded for by two HBB genes. A person with the disorder has the genotype SS, meaning they have two copies of the mutated HBB gene. A healthy individual has the genotype AA, with no mutated copies of the HBB gene.The genotype AS is referred to as sickle-cell trait possessing. An individual with this genotype is considered a carrier and will usually not experience complications from their genotype unless extreme conditions arise from altitude, intense exercise, or dehydration. Uniquely, this carrier has an advantage over both the homozygous genotypes. Heterozygous individuals are less likely to acquire malaria than either homozygous individual due to the sickle cell making it more difficult for the malaria parasite to grow.

Practice Questions

Section Summary

Gene mutations, which are changes in DNA sequences inside coding regions of genes, or in the regulatory regions upstream of the gene, can be broadly categorized into point mutations, insertions/deletions (indels). Point mutations involve a single base change, while indels involve the addition or removal of DNA segments. Point mutations may be: 1) substitutions, where one base is replaced by another; missense mutations, where the substitution results in a different amino acid being incorporated into the protein; nonsense mutations, where the substitution creates a premature stop codon, leading to a truncated and often nonfunctional protein; or silent mutations, in which the substitution does not change the amino acid sequence due to the redundancy of the genetic code. Insertions/Deletions (Indels) result in one or more nucleotides being inserted or deleted. Frameshift mutations occur when the number of inserted or deleted nucleotides is not a multiple of three, it shifts the reading frame of the gene, altering the amino acid sequence downstream of the mutation.

Sickle cell anemia is a well-studied example of how a single substitution missense mutation can have dire effects on the health of the affected individual.

Figure Descriptions

Figure 14.7.1. A diagram categorizes point mutations into silent, nonsense, and missense types, compared with a “no mutation” reference. For each type, the DNA codon, mRNA codon, and resulting protein change are shown. In the no-mutation example, the DNA sequence TTC transcribes to mRNA AAG, coding for lysine. A silent mutation changes DNA to TTT (mRNA AAA) but still codes for lysine. A nonsense mutation changes DNA to ATC (mRNA UAG), introducing a stop codon. A conservative missense mutation changes DNA to TCC (mRNA AGG), replacing lysine with arginine. A non-conservative missense mutation changes DNA to TGC (mRNA ACG), replacing lysine with threonine. The diagram also shows simplified structural formulas for the amino acids, with lysine and arginine labeled as basic and threonine as polar. [Return to Figure 14.7.1]

Figure 14.7.2. The diagram compares an original mRNA sequence to one altered by a frameshift mutation. In the original sequence, the codons AGC GUA CCU AC code for the amino acids serine, valine, proline, and tyrosine. After the mutation, the sequence is read as AGC GCC UAC UU, coding for serine, alanine, leucine, and leucine. The shift in codon grouping results in a completely different set of amino acids from the mutation point onward. [Return to Figure 14.7.2]

Figure 14.7.3. The top portion shows a normal capillary with smooth, round red blood cells moving freely, represented by an arrow pointing forward. An inset box depicts the shape of a healthy red blood cell (disc-shaped) and a sickle-shaped red blood cell (crescent-shaped) for comparison. The bottom portion shows a capillary affected by sickle cell anemia, where multiple sickle-shaped red blood cells are clustered and misshapen, obstructing blood flow. [Return to Figure 14.7.3]

Figure 14.7.4. The left map shows the distribution of malaria across Africa, with dark shading covering much of central, western, and parts of eastern Africa, and smaller regions in northern Africa, indicating malaria presence. The right map shows sickle-cell trait prevalence using four shaded ranges: >20% (darkest), 15–20%, 1–10%, and <1% (white). High prevalence of sickle-cell trait is concentrated in central Africa, overlapping significantly with malaria-endemic regions shown in the left map. [Return to Figure 14.7.4]

Licenses and Attributions

Media Attributions

- Point-mutations

- Sickle_Cell_Anemia

- Malaria_versus_sickle-cell_trait_distributions