4.2 Plasma Membrane Structure and Components

Christelle Sabatier

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe phospholipid, protein, and carbohydrate functions in membranes.

- Explain how membrane fluidity impacts cell function.

A cell’s plasma membrane defines the cell, outlines its borders, and determines the nature of its interaction with its environment. Cells exclude some substances, take in others, and excrete still others, all in controlled quantities. The plasma membrane must be very flexible to allow certain cells, such as red and white blood cells, to change shape as they pass through narrow capillaries. These are the more obvious plasma membrane functions. In addition, the plasma membrane’s surface carries markers that allow cells to recognize one another, which is vital for tissue and organ formation during early development, and which later plays a role in the immune response’s “self” versus “non-self” distinction.

Among the most sophisticated plasma membrane functions is the ability for complex, integral proteins, receptors to transmit signals. These proteins act both as extracellular input receivers and as intracellular processing activators. These membrane receptors provide extracellular attachment sites for effectors like hormones and growth factors, and they activate intracellular response cascades when their effectors are bound. Occasionally, viruses hijack receptors (HIV, human immunodeficiency virus, is one example) that use them to gain entry into cells, and at times, the genes encoding receptors become mutated, causing the signal transduction process to malfunction with disastrous consequences.

Fluid Mosaic Model

Scientists identified the plasma membrane in the 1890s, and its chemical components in 1915. The principal components they identified were lipids and proteins. In 1935, Hugh Davson and James Danielli proposed the plasma membrane’s structure. This was the first model that others in the scientific community widely accepted. It was based on the plasma membrane’s “railroad track” appearance in early electron micrographs. Davson and Danielli theorized that the plasma membrane’s structure resembles a sandwich. They made the analogy of proteins to bread, and lipids to the filling. In the 1950s, advances in microscopy, notably transmission electron microscopy (TEM), allowed researchers to see that the plasma membrane’s core consisted of a double, rather than a single, layer. In 1972, S. J. Singer and Garth L. Nicolson proposed a new model that provides microscopic observations and better explains plasma membrane function.

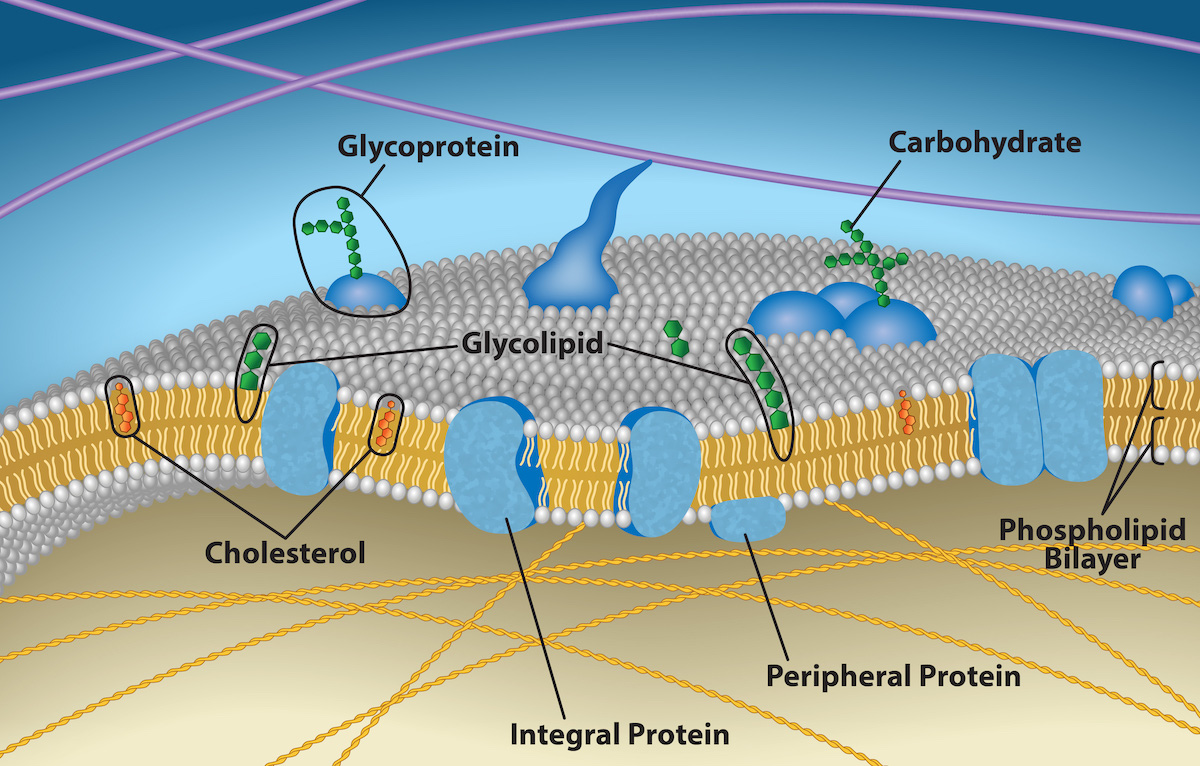

The explanation, the fluid mosaic model, has evolved somewhat over time, but it still best accounts for plasma membrane structure and function as we now understand them. The fluid mosaic model describes the plasma membrane structure as a mosaic of components—including phospholipids, cholesterol, proteins, and carbohydrates—that gives the membrane a fluid character. Plasma membranes range from 5 to 10 nm in thickness. For comparison, human red blood cells, visible via light microscopy, are approximately 8 µm wide, or approximately 1,000 times wider than a plasma membrane. The membrane does look a bit like a sandwich (Figure 4.2.1).

A plasma membrane’s principal components are lipids (phospholipids and cholesterol), proteins, and carbohydrates attached to some of the lipids and proteins. A phospholipid is a molecule consisting of glycerol, two fatty acids, and a phosphate-linked head group. Cholesterol, another lipid comprised of four fused carbon rings, is situated alongside the phospholipids in the membrane’s core.

The protein, lipid, and carbohydrate proportions in the plasma membrane vary with cell type, but for a typical human cell, protein accounts for about 50% of the composition by mass, lipids (of all types) account for about 40%, and carbohydrates comprise the remaining 10%. However, protein and lipid concentration varies with different cell membranes. For example, myelin, an outgrowth of specialized cells’ membrane that insulates the peripheral nerves’ axons, contains only 18% protein and 76% lipid. The mitochondrial inner membrane contains 76% protein and only 24% lipid. The plasma membrane of human red blood cells is 30% lipid. Carbohydrates are present only on the plasma membrane’s exterior surface and are attached to proteins, forming glycoproteins, or attached to lipids, forming glycolipids.

Phospholipids

The membrane’s main fabric comprises amphiphilic, phospholipid molecules. The hydrophilic or “water-loving” areas of these molecules (which look like a collection of balls in an artist’s rendition of the model) (Figure 4.2.1) are in contact with the aqueous fluid both inside and outside the cell. Hydrophobic, or water-hating molecules, tend to be non-polar. They interact with other non-polar molecules in chemical reactions, but generally do not interact with polar molecules. When placed in water, hydrophobic molecules tend to form a ball or cluster. The phospholipids’ hydrophilic regions form hydrogen bonds with water and other polar molecules on both the cell’s exterior and interior. Thus, the membrane surfaces that face the cell’s interior and exterior are hydrophilic. In contrast, the cell membrane’s interior is hydrophobic and will not interact with water. Therefore, phospholipids form an excellent two-layer cell membrane that separates fluid within the cell from the fluid outside the cell.

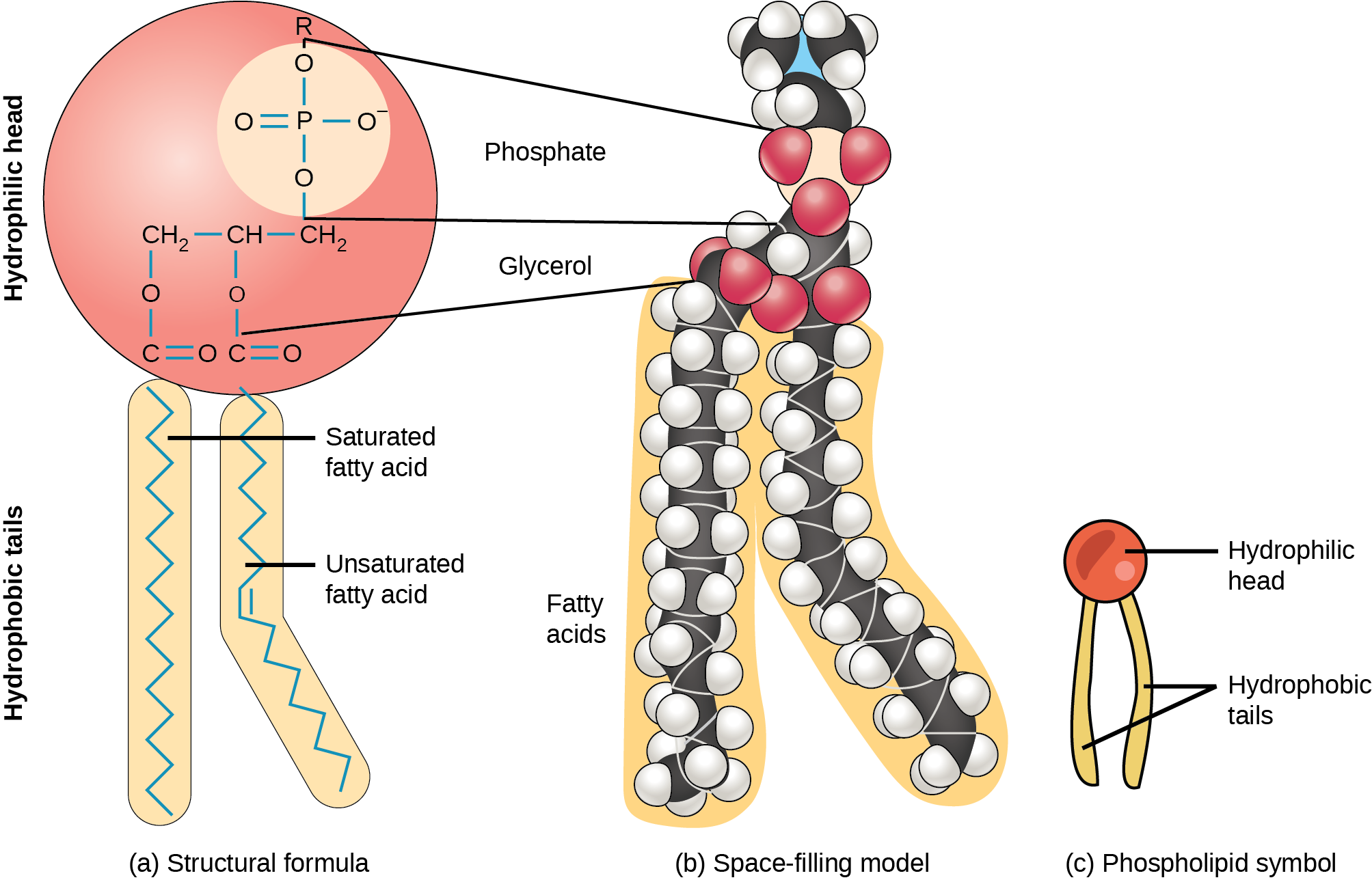

A phospholipid molecule (Figure 4.2.2) consists of a three-carbon glycerol backbone with two fatty acid molecules attached to carbons 1 and 2, and a phosphate-containing group attached to the third carbon. This arrangement gives the overall molecule a head area (the phosphate-containing group), which has a polar character or negative charge, and a tail area (the fatty acids), which has no charge. The head can form hydrogen bonds, but the tail cannot. Scientists call a molecule with a positively or negatively charged area and an uncharged, or non-polar, area amphiphilic or “dual-loving.”

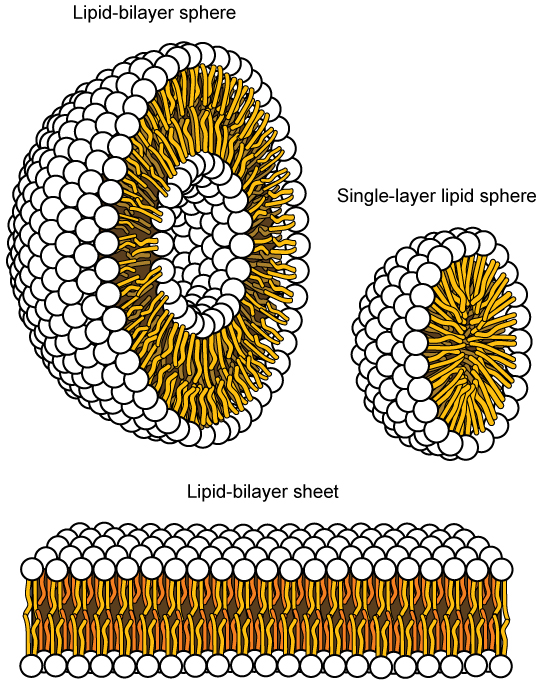

This characteristic is vital to the plasma membrane’s structure because, in water, phospholipids arrange themselves with their hydrophobic tails facing each other and their hydrophilic heads facing out. In this way, they form a phospholipid bilayer—a double-layered phospholipid barrier that separates the water and other materials on one side from the water and other materials on the other side. Phospholipids heated in an aqueous solution usually spontaneously form small spheres or droplets (micelles or liposomes), with their hydrophilic heads forming the exterior and their hydrophobic tails on the inside (Figure 4.2.3).

Proteins

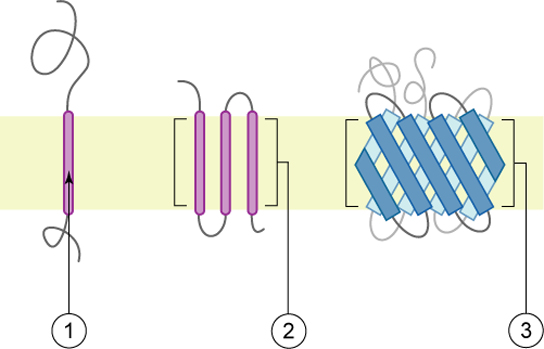

Proteins comprise the plasma membranes’ second major component. Integral proteins, or integrins, as their name suggests, integrate completely into the membrane structure, and their hydrophobic membrane-spanning regions interact with the phospholipid bilayer’s hydrophobic region (Figure 4.2.1). Single-pass integral membrane proteins usually have a hydrophobic transmembrane segment that consists of 20 to 25 amino acids. Some span only part of the membrane—associating with a single layer—while others stretch from one side to the other, and are exposed on either side. Up to 12 single protein segments comprise some complex proteins, which are extensively folded and embedded in the membrane (Figure 4.2.4). This protein type has a hydrophilic region or regions, and one or several mildly hydrophobic regions. This arrangement of protein regions orients the protein alongside the phospholipids, with the protein’s hydrophobic region adjacent to the phospholipids’ tails and the protein’s hydrophilic region or regions protruding from the membrane and in contact with the cytosol or extracellular fluid.

Peripheral proteins are on the membranes’ exterior and interior surfaces, attached either to integral proteins or to phospholipids. Peripheral proteins, along with integral proteins, may serve as enzymes, as structural attachments for the cytoskeleton’s fibers, or as part of the cell’s recognition sites.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are the third major plasma membrane component. They are always on the cells’ exterior surface and are bound either to proteins (forming glycoproteins) or to lipids (forming glycolipids) (Figure 4.2.1). These carbohydrate chains may consist of 2 to 60 monosaccharide units and can be either straight or branched. Along with peripheral proteins, carbohydrates form specialized sites on the cell surface that allow cells to recognize each other. These sites have unique patterns that allow for cell recognition, much the way that the facial features unique to each person allow individuals to recognize him or her. This recognition function is very important to cells, as it allows the immune system to differentiate between body cells (“self”) and foreign cells or tissues (“non-self”). Similar glycoprotein and glycolipid types are on the surfaces of viruses and may change frequently, preventing immune cells from recognizing and attacking them.

Due to the presence of these carbohydrates, the cell’s exterior surface is highly hydrophilic and attracts large amounts of water to the cell’s surface. This aids in the cell’s interaction with its watery environment and in the cell’s ability to obtain substances dissolved in the water.

Membrane Fluidity

The membrane’s mosaic characteristic helps to illustrate its nature. The integral proteins and lipids exist in the membrane as separate but loosely attached molecules. These resemble the separate, multicolored tiles of a mosaic picture, and they float, moving somewhat with respect to one another. The membrane is not like a balloon, however, that can expand and contract; rather, it is fairly rigid and can burst if penetrated or if a cell takes in too much water. However, because of its mosaic nature, a very fine needle can easily penetrate a plasma membrane without causing it to burst, and the membrane will flow and self-seal when one extracts the needle.

The membrane’s mosaic characteristics explain some but not all of its fluidity. There are two other factors that help maintain this fluid characteristic. One factor is the nature of the phospholipids themselves. In their saturated form, the fatty acids in phospholipid tails are saturated with bound hydrogen atoms. There are no double bonds between adjacent carbon atoms. This results in tails that are relatively straight. In contrast, unsaturated fatty acids do not contain a maximal number of hydrogen atoms, but they do contain some double bonds between adjacent carbon atoms. A double bond results in a bend in the carbon string of approximately 30 degrees (Figure 4.2.2).

Thus, if decreasing temperatures compress saturated fatty acids with their straight tails, they press in on each other, making a dense and fairly rigid membrane. If unsaturated fatty acids are compressed, the “kinks” in their tails elbow adjacent phospholipid molecules away, maintaining some space between the phospholipid molecules. This “elbow room” helps to maintain fluidity in the membrane at temperatures at which membranes with saturated fatty acid tails in their phospholipids would “freeze” or solidify. The membrane’s relative fluidity is particularly important in a cold environment. A cold environment usually compresses membranes comprised largely of saturated fatty acids, making them less fluid and more susceptible to rupturing. Many organisms (fish are one example) are capable of adapting to cold environments by changing the proportion of unsaturated fatty acids in their membranes in response to lower temperature.

Video 4.2.1. Fluid Mosaic Model of the Cell Membrane by Wesley McCammon

Animals have an additional membrane constituent that assists in maintaining fluidity. Cholesterol, which lies alongside the phospholipids in the membrane, tends to dampen temperature effects on the membrane. Thus, this lipid functions as a buffer, preventing lower temperatures from inhibiting fluidity and preventing increased temperatures from increasing fluidity too much. Thus, cholesterol extends, in both directions, the temperature range in which the membrane is appropriately fluid and consequently functional. Cholesterol also serves other functions, such as organizing clusters of transmembrane proteins into lipid rafts.

Practice Questions

Glossary

plasma membrane

protective membrane made of double-lipid layer that encloses all cells and contains specialized components (proteins, lipids, etc.) depending on the cell function

phospholipid bilayer

a two-layered arrangement of phospholipid molecules that form a thin membrane around and within cells, the hydrophobic fatty acid ends facing inward and the hydrophilic phosphate ends facing outward.

Figure Descriptions

Figure 4.2.1. The image is a detailed, schematic representation of a cell membrane, illustrating its various components. The membrane is depicted as a double layer of phospholipids, visible as two parallel lines composed of small, spherical molecules, forming the phospholipid bilayer. Within this bilayer, several other structures are labeled. Blue, globular proteins are embedded across the membrane, labeled as “Integral Protein.” Smaller blue proteins are attached externally to the membrane, marked as “Peripheral Protein.” Sprigs of carbohydrates extend outward from glycoproteins and glycolipids, which are integrated within the lipid bilayer. Green hexagonal shapes represent carbohydrate chains linked to these proteins and lipids. Cholesterol molecules, shown as orange rings, are interspersed within the lipid bilayer. The overall color palette includes shades of blue, green, orange, and white, set against a gradient background transitioning from light blue at the top to yellow at the bottom. [Return to Figure 4.2.1]

Figure 4.2.2. The image illustrates three representations of a phospholipid. On the left, part (a) labeled “Structural formula” shows a detailed chemical structure with a large red circle depicting the hydrophilic head containing a phosphate group, and two elongated beige shapes representing hydrophobic tails. One tail is straight, indicating a saturated fatty acid, while the other is kinked, indicating an unsaturated fatty acid. The central part (b) labeled “Space-filling model” depicts a 3D model with colorful spheres. Red spheres represent the polar head group while connected chains of black and white spheres depict the nonpolar tails. On the right, part (c) labeled “Phospholipid symbol” shows a simplified illustration with a red circle for the hydrophilic head and two beige lines extending downward as hydrophobic tails. [Return to Figure 4.2.2]

Figure 4.2.3. The image illustrates three structures of lipid arrangements. On the top left, there is a depiction of a “Lipid-bilayer sphere” showing a cross-section of a spherical shape composed of two layers. The outer layers consist of white spheres representing the hydrophilic (water-attracting) heads, and yellow lines indicating the hydrophobic (water-repelling) tails positioned in the middle. On the top right is a “Single-layer lipid sphere,” a smaller sphere with a single layer of lipids arranged similarly, with the heads outward and tails inward. At the bottom, a “Lipid-bilayer sheet” is shown, representing a cross-section of a flat bilayer. The arrangement is similar, with the white spheres on the outer sides and yellow tails facing each other in the center. [Return to Figure 4.2.3]

Figure 4.2.4. The image is an illustration of transmembrane protein structures within a cell membrane, depicted as a horizontal yellow-green band. There are three distinct structures labeled with numbered circles. Number 1 shows a single purple helix traversing the membrane and extending outward with a squiggly line. Number 2 features a cluster of four parallel purple helices crossing the membrane. Number 3 displays a series of blue, crisscrossed beta-pleated sheets forming a barrel-like structure. Gray, curly lines extend from all structures, representing the protein segments outside the membrane. [Return to Figure 4.2.4]

Licenses and Attributions

“4.2 Plasma Membrane Structure and Components” is adapted from “5.1 Components and Structure” by Mary Ann Clark, Matthew Douglas, and Jung Choi for OpenStax Biology 2e under CC-BY 4.0. “4.2 Plasma Membrane Structure and Components” is licensed under CC-BY-NC 4.0.

Media Attributions

- 5.5 Cell Membrane with Proteins-XYZZ © Rao, A., Ryan, K., Fletcher, S., Hawkins, A. and Tag, A. is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 1A.B.6 Phospholipids © OpenStax Biology 2e is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 1A.B.6 Phospholipid structures © Mariana Ruiz Villareal adapted by Modified by OpenStax Biology 2e is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 1A.B.6 Membrane Proteins © Foobar/Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

a molecule with hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions

a two-layered arrangement of phospholipid molecules that form a thin membrane around and within cells, the hydrophobic fatty acid ends facing inward and the hydrophilic phosphate ends facing outward.