6.1 Exponential and Logistic Population Growth

Dawn Hart

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Explain the characteristics of and differences between exponential and logistic growth patterns.

- Give examples of exponential and logistic growth in natural populations.

- Define carrying capacity (K) and determine if a change in carrying capacity has occurred in a population.

- Determine how competition might impact population growth.

Population ecologists make use of a variety of methods to model population dynamics mathematically. These models can be used to accurately describe changes occurring in a population and better predict future changes. Certain models that have been accepted for decades are now being modified or even abandoned due to their lack of predictive ability, and scholars strive to create effective new models. In this chapter we will introduce two seminal and relatively simplistic population growth models (e.g., exponential and logistic growth models) to get us started exploring how populations change over time.

Exponential Growth

Charles Darwin, in his theory of natural selection, was greatly influenced by the English clergyman Thomas Malthus. Malthus published a book in 1798 stating that populations with unlimited natural resources grow very rapidly, and then population growth decreases as resources become depleted. This accelerating pattern of increasing population size is called exponential growth.

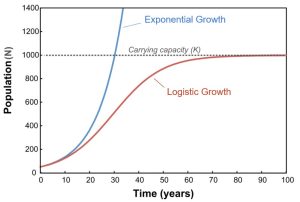

The best example of exponential growth is seen in bacteria. Bacteria are prokaryotes that reproduce by prokaryotic fission. This division takes about an hour for many bacterial species. If 1,000 bacteria are placed in a large flask with an unlimited supply of nutrients (so the nutrients will not become depleted), after an hour, there is one round of division and each organism divides, resulting in 2,000 organisms—an increase of 1,000. In another hour, each of the 2,000 organisms will double, producing 4,000, an increase of 2,000 organisms. After the third hour, there should be 8,000 bacteria in the flask, an increase of 4,000 organisms. The important concept of exponential growth is that the population growth rate—the number of organisms added in each reproductive generation—is accelerating; that is, it is increasing at a greater and greater rate. After 1 day and 24 of these cycles, the population would have increased from 1,000 to more than 16 billion. When the population size, N, is plotted over time, a J-shaped growth curve is produced (see the blue line on the graph in Figure 6.1.1).

The bacteria example is not representative of the real world where resources are limited. Furthermore, some bacteria will die during the experiment and thus not reproduce, lowering the growth rate. Therefore, when calculating the growth rate of a population, the death rate (D) (number organisms that die during a particular time interval) is subtracted from the birth rate (B) (number organisms that are born during that interval). This is shown in the following formula:

Change in the population growth rate = B (birth rate) - D (death rate)

The birth rate is usually expressed on a per capita (for each individual) basis. Thus, B (birth rate) = bN (the per capita birth rate “b” multiplied by the number of individuals “N”) and D (death rate) =dN (the per capita death rate “d” multiplied by the number of individuals “N”). Additionally, ecologists are interested in the population at a particular point in time, an infinitely small time interval. For this reason, the terminology of differential calculus is used to obtain the “instantaneous” growth rate, replacing the change in the population growth rate with an instant-specific measurement of number and time:

[latex]\frac{dN}{dt} = bN - dN = (b-d)N[/latex]

Notice that the “d” associated with the first term refers to the derivative (as the term is used in calculus) and is different from the death rate, also called “d.” The difference between birth (b) and death (d) rates is further simplified by substituting the term “r” (per capita growth rate) for the relationship between birth and death rates:

[latex]\frac{dN}{dt} = rN[/latex]

The value “r” can be positive, meaning the population is increasing in size; or negative, meaning the population is decreasing in size; or zero, where the population’s size is unchanging, a condition known as zero population growth.

When resources are unlimited, populations exhibit exponential growth, resulting in a J-shaped curve. Populations experiencing unlimited resources is very uncommon in nature. To account for the fact that most populations do experience resource limitation, the exponential growth equation can be modified. The resulting equation is known as the logistic growth equation.

When resources are limited, populations exhibit logistic growth. In logistic growth, population expansion decreases as resources become scarce, and it levels off when the carrying capacity of the environment is reached, resulting in an S-shaped curve (see the red line on the graph in Figure 6.1.1).

Logistic Growth

Exponential growth is possible only when infinite natural resources are available; this is not the case in the real world. Charles Darwin recognized this fact in his description of the “struggle for existence,” which states that individuals will compete (with members of their own or other species) for limited resources. The successful ones will survive to pass on their own characteristics and traits (which we know now are transferred by genes) to the next generation at a greater rate (natural selection). To model the reality of limited resources, population ecologists developed the logistic growth model.

Carrying Capacity and the Logistic Model

In the real world, with its limited resources, exponential growth cannot continue indefinitely. Exponential growth may occur in environments where there are few individuals and plentiful resources, but when the number of individuals gets large enough, resources will be depleted, slowing the growth rate. Eventually, the growth rate will plateau or level off. This population size, which represents the maximum population size that a particular environment can support, is called the carrying capacity, or K (see the black dotted line in Figure 6.1.1).

The formula we use to calculate logistic growth adds the carrying capacity as a moderating force in the growth rate. The expression “K – N” is indicative of how many individuals may be added to a population at a given stage, and “K – N” divided by “K” is the fraction of the carrying capacity available for further growth. Thus, the exponential growth model is restricted by this factor to generate the logistic growth equation:

[latex]\frac{dN}{dt} = rN\left(\frac{K - N}{K}\right)[/latex]

Notice that when N is very small, (K-N)/K becomes close to K/K or 1, and the right side of the equation reduces to rN, which means the population is growing exponentially and is not influenced by carrying capacity. On the other hand, when N is large, (K-N)/K come close to zero, which means that population growth will be slowed greatly or even stopped. Thus, population growth is greatly slowed in large populations by the carrying capacity K. This model also allows for the population of a negative population growth, or a population decline. This occurs when the number of individuals in the population exceeds the carrying capacity (because the value of (K-N)/K is negative).

A graph of this equation yields an S-shaped curve, and it is a more realistic model of population growth than exponential growth. There are three different sections to an S-shaped curve. Initially, growth is exponential because there are few individuals and ample resources available. Then, as resources begin to become limited, the growth rate decreases. Finally, growth levels off at the carrying capacity of the environment, with little change in population size over time.

Test Your Knowledge

Role of Intraspecific Competition

The logistic model assumes that every individual within a population will have equal access to resources and, thus, an equal chance for survival. For plants, the amount of water, sunlight, nutrients, and the space to grow are the important resources, whereas in animals, important resources include food, water, shelter, nesting space, and mates.

In the real world, phenotypic variation among individuals within a population means that some individuals will be better adapted to their environment than others. The resulting competition between population members of the same species for resources is termed intraspecific competition (intra- = “within”; -specific = “species”). Intraspecific competition for resources may not affect populations that are well below their carrying capacity—resources are plentiful and all individuals can obtain what they need. However, as population size increases, this competition intensifies and individuals in a population will find themselves with insufficient resources to sustain exponential growth within the population.

Examples of Logistic Growth

Yeast, a microscopic fungus used to make bread and alcoholic beverages, exhibits the classical S-shaped curve when grown in a test tube (Figure 6.1.2A). Its growth levels off as the population depletes the nutrients that are necessary for its growth. In the real world, however, there are variations to this idealized curve. In wild populations of harbor seals (Figure 6.1.2B) the population grows exponentially and then levels off at the carrying capacity, however, in this population there is much more scatter in the data. The population size exceeds the carrying capacity for short periods of time and then falls below the carrying capacity afterwards. This fluctuation in population size continues to occur as the population oscillates around its carrying capacity. Still, even with this oscillation, the logistic model is confirmed.

Practice Questions

-

Glossary

- birth rate (B)

- number of births within a population at a specific point in time

- carrying capacity (K)

- number of individuals of a species that can be supported by the amount of resources available in an environment

- death rate (D)

- number of deaths within a population at a specific point in time

- exponential growth

- accelerating growth pattern seen in species under conditions where resources are not limiting (resulting in a J-shaped curve on a graph)

- intraspecific competition

- competition between members of the same species

- logistic growth

- leveling off of exponential growth due to limiting resources (resulting in a S-shaped curve on a graph)

- population growth rate

- number of organisms added in each reproductive generation

- zero population growth

- steady population size where birth rates and death rates are equal

Figure Descriptions

Figure 6.1.1. Line graph with Time (years) on the x-axis (0–100) and Population (N) on the y-axis (0–1400). A dashed horizontal line labeled Carrying capacity (K) sits near N = 1000. The blue exponential curve starts low, rises slowly, then shoots steeply upward, crossing the line and continuing above it (a J-shape). The red logistic curve also starts low and rises, but its slope decreases as it approaches the dashed line, flattening just below it (an S-shape). The figure contrasts unbounded exponential growth with density-limited logistic growth that stabilizes near the carrying capacity. [Return to Figure 6.1.1]

Figure 6.1.2. The image is divided into two labeled sections, "A" and "B". Section A: On the left side, there is a grayscale micrograph showing three yeast cells of varying sizes. The cells are spherical and have a smooth texture. On the right side, there's a graph with a black background. It features orange data points connected by a blue curve, which rises steeply and then levels off as it approaches a horizontal red dashed line near the top. Section B: On the left, there is a color photograph of a spotted seal lying on a rock by the water. The background is blurry, suggesting a focus on the seal itself. On the right side, similar to section A, there's a graph with orange data points and a blue curve on a black background, displaying a similar trend as the graph in section A. A red dashed line appears near the top. [Return to Figure 6.1.2]

Licenses and Attributions

"6.1 Exponential and Logistic Population Growth" is adapted from "45.3 Environmental Limits to Population Growth" by Mary Ann Clark, Matthew Douglas, and Jung Choi for OpenStax Biology 2e under CC-BY 4.0. "6.1 Exponential and Logistic Population Growth" is licensed under CC-BY-NC 4.0.

Media Attributions

- population growth graph examples © Dawn Hart modified from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Population_growth.png is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- yeast and harbor seal population growth curves © Dawn Hart modified from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-ecology/chapter/environmental-limits-to-population-growth/ is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license