3.5 Lipid Structure and Function

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe the four major types of lipids.

- Explain the role of fats in storing energy.

- Differentiate between saturated and unsaturated fatty acids.

- Define the basic structure of a steroid and some steroid functions.

Lipids include a diverse group of compounds that are largely nonpolar in nature. This is because they are primarily composed of hydrocarbons that include mostly nonpolar carbon–carbon (C–C) or carbon–hydrogen (C–H) bonds. Non-polar molecules are hydrophobic (“water fearing”). Lipids perform many different functions in a cell. Cells store energy for long-term use in the form of fats. Lipids also provide insulation from the environment for plants and animals. For example, they help keep aquatic birds and mammals dry when forming a protective layer over fur or feathers because of their water-repellant hydrophobic nature. Lipids are also the building blocks of many hormones and are an important constituent of all cellular membranes. Lipids include fats, oils, waxes, phospholipids, and steroids.

Fats and Oils

A fat molecule consists of two main components—glycerol and fatty acids. Glycerol is an organic compound (alcohol) with three carbons, five hydrogens, and three hydroxyl (OH) groups. Fatty acids have a long chain of hydrocarbons to which a carboxyl group is attached, hence the name “fatty acid.” The number of carbons in the fatty acid may range from 4 to 36. The most common are those containing 12 to 18 carbons.

In a fat molecule, the fatty acids attach to each of the glycerol molecule’s three carbons.

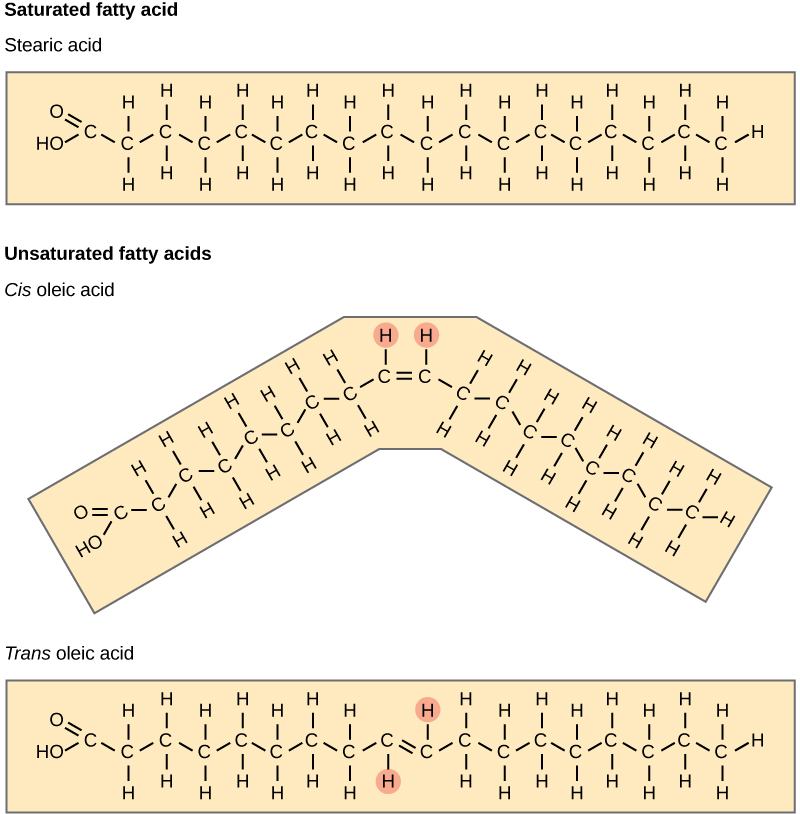

The three fatty acids in the triglyceride may be similar or dissimilar. Fatty acids may be saturated or unsaturated. In a fatty acid chain, if there are only single bonds between neighboring carbons in the hydrocarbon chain, the fatty acid is saturated. Saturated fatty acids are saturated with hydrogen. In other words, the number of hydrogen atoms attached to the carbon skeleton is maximized. When a fatty acid has no double bonds, it is a saturated fatty acid because it is not possible to add more hydrogen to the chain’s carbon atoms.

A fat may contain similar or different fatty acids attached to glycerol. Long straight fatty acids with single bonds generally pack tightly and are solid at room temperature. Animal fats with stearic acid and palmitic acid (common in meat) and the fat with butyric acid (common in butter) are examples of saturated fats. Mammals store fats in specialized cells, or adipocytes, where fat globules occupy most of the cell’s volume.

When the hydrocarbon chain contains a double bond, the fatty acid is unsaturated. Oleic acid is an example of an unsaturated fatty acid.

Most unsaturated fats are liquid at room temperature. We call these oils. If there is one double bond in the molecule, then it is a monounsaturated fat (e.g., olive oil), and if there is more than one double bond, then it is a polyunsaturated fat (e.g., canola oil).

Plants commonly store fat or oil in many seeds and use them as a source of energy during seedling development. Unsaturated fats or oils are usually of plant origin and contain cis unsaturated fatty acids. Cis and trans indicate the configuration of the molecule around the double bond. If hydrogens are present on the same side of the C-C bond, it is a cis fat. If the hydrogen atoms are on two different sides of the C-C bond, it is a trans fat. The cis double bond causes a bend or a “kink” that prevents the fatty acids from packing tightly, and from forming as many van der Waals interactions between them, keeping them liquid at room temperature. Olive oil, corn oil, canola oil, and cod liver oil are examples of unsaturated fats.

Trans Fats

The food industry artificially hydrogenates oils to make them semi-solid and of a consistency desirable for many processed food products. Simply speaking, hydrogen gas is bubbled through oils to solidify them. During this hydrogenation process, double bonds of the cis– conformation in the hydrocarbon chain may convert to double bonds in the trans– conformation.

Margarine, some types of peanut butter, and shortening are examples of artificially hydrogenated trans fats. Recent studies have shown that an increase in trans fats in the human diet may lead to higher levels of low-density lipoproteins (LDL), or “bad” cholesterol, which in turn may lead to plaque deposition in the arteries, resulting in heart disease. Many fast food restaurants have recently banned using trans fats, and food labels are required to display the trans fat content.

Waxes

Waxes are a type of single chain hydrocarbon lipid. Wax covers some aquatic birds’ feathers and some plants’ leaf surfaces. Because of waxes’ hydrophobic nature, they prevent water from sticking on the surface.

Phospholipids

Phospholipids are the major components of cell membranes. Like fats, most phospholipids are comprised of fatty acid chains attached to a glycerol backbone. However, instead of three fatty acids attached as in triglycerides, there are two fatty acids, and a modified phosphate group is attached to the glycerol’s third carbon.

A phospholipid is an amphipathic molecule, meaning it has a hydrophobic and ahydrophilic part. The fatty acid chains are hydrophobic and cannot interact with water; whereas, the phosphate-containing group is hydrophilic and interacts with water. You will have a chance to explore phospholipids in more details in Section 4.1 Plasma Membrane Structure and Components

Steroids

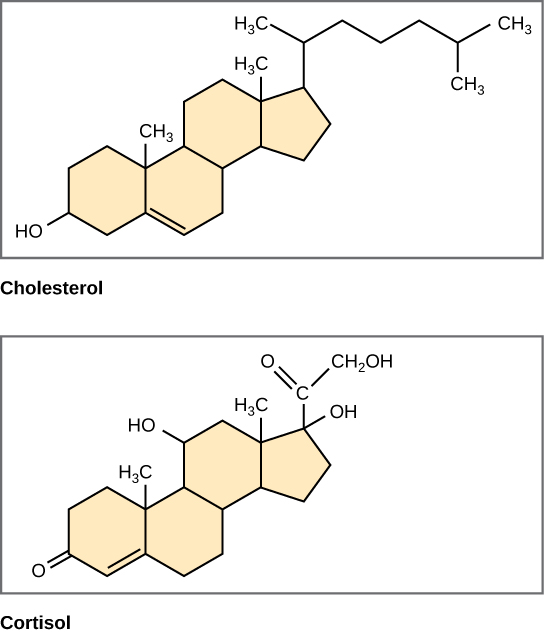

Unlike phospholipids and fats, steroids have a fused ring structure. Although they do not resemble the other lipids, scientists group them with them because they are also hydrophobic and insoluble in water. All steroids have four linked carbon rings and several of them, like cholesterol, have a short tail. Many steroids also have a hydroxyl group, which makes them alcohols (sterols).

Figure 3.5.8. Four fused hydrocarbon rings comprise steroids such as cholesterol and cortisol. [Image Description]

Cholesterol is the most common steroid. The liver synthesizes cholesterol. It is the precursor to many steroid hormones such as testosterone and estradiol, as well as Vitamin D, and bile salts. Cholesterol is absolutely necessary for the body’s proper functioning. Sterols (cholesterol in animal cells, phytosterol in plants) are components of the plasma membrane of cells and are found within the phospholipid bilayer.

Video 3.5.1. Biomolecules – The Lipids by Wisc-Online

Practice Questions

Glossary

phospholipid

cell membranes’ major constituent; comprised of two fatty acids and a phosphate-containing group attached to a glycerol backbone

triglyceride

fat molecule; consists of three fatty acids linked to a glycerol molecule

fatty acid

ong chain of hydrocarbons to which a carboxyl group is attached

glycerol

organic compound (alcohol) with three carbons, five hydrogens, and three hydroxyl (OH) groups

saturated fat

long-chain hydrocarbon with single covalent bonds in the carbon chain; the number of hydrogen atoms attached to the carbon skeleton is maximized

unsaturated fatty acid

long-chain hydrocarbon that has one or more double bonds in the hydrocarbon chain

steroid

type of lipid comprised of four fused hydrocarbon rings forming a planar structure. Cholesterol is a type of steroid.

Figure Descriptions

Figure 3.5.1. The image depicts a bird known as a great crested grebe floating on a calm body of blue water. The grebe has a pointed beak, red eyes, and distinctive plumage. Its head features a black crown and a reddish-brown ruff encircling the neck. The bird’s body is a mix of brown and white feathers with a streamlined form allowing it to glide smoothly on the water’s surface. Slight ripples around the bird suggest gentle movement. [Return to Figure 3.5.1]

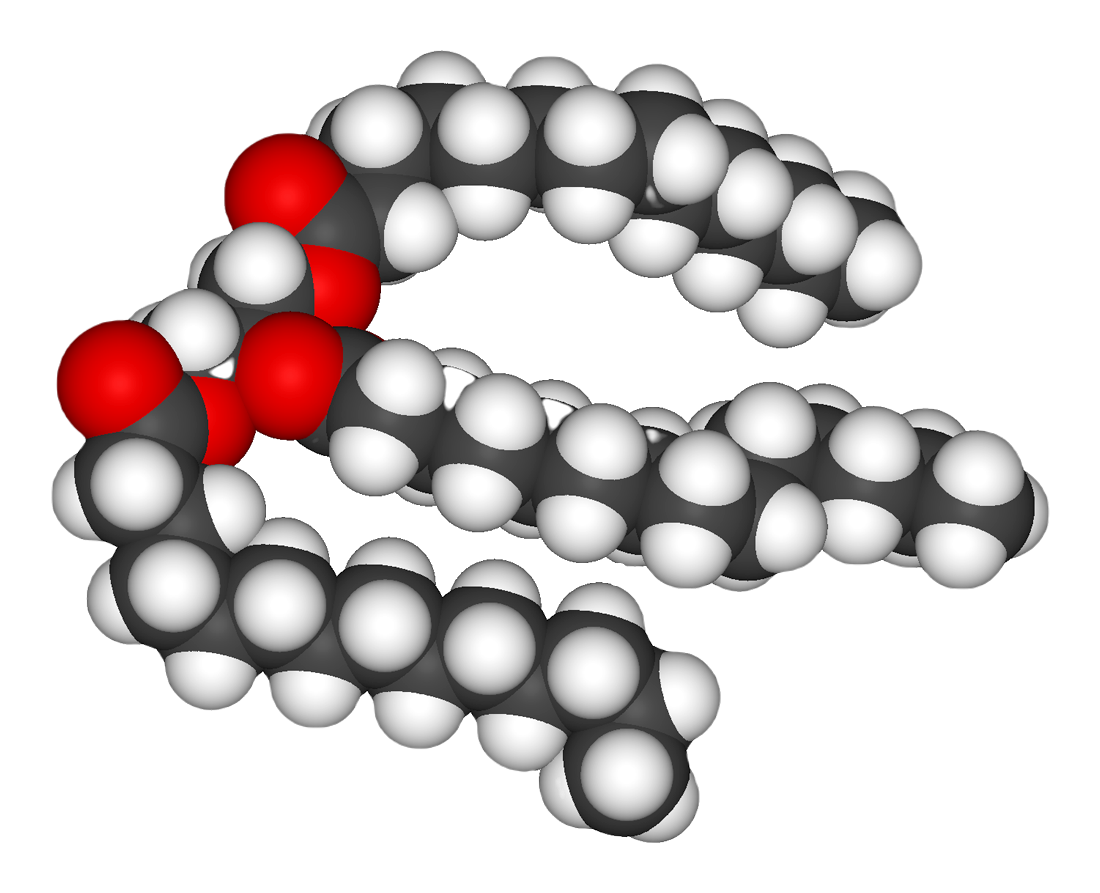

Figure 3.5.2. The image depicts a space-filling molecular model of a fat molecule. It consists of interconnected spheres representing atoms, with three distinct colors to differentiate each type. The red spheres symbolize oxygen atoms, the gray spheres are carbon atoms, and the white spheres represent hydrogen atoms. The arrangement forms a single large, curved chain, indicative of a fatty acid structure. The red spheres are clustered at one end, serving as a functional group in the molecule, while the intertwined gray and white spheres extend outwards, forming the hydrocarbon tail. [Return to Figure 3.5.2]

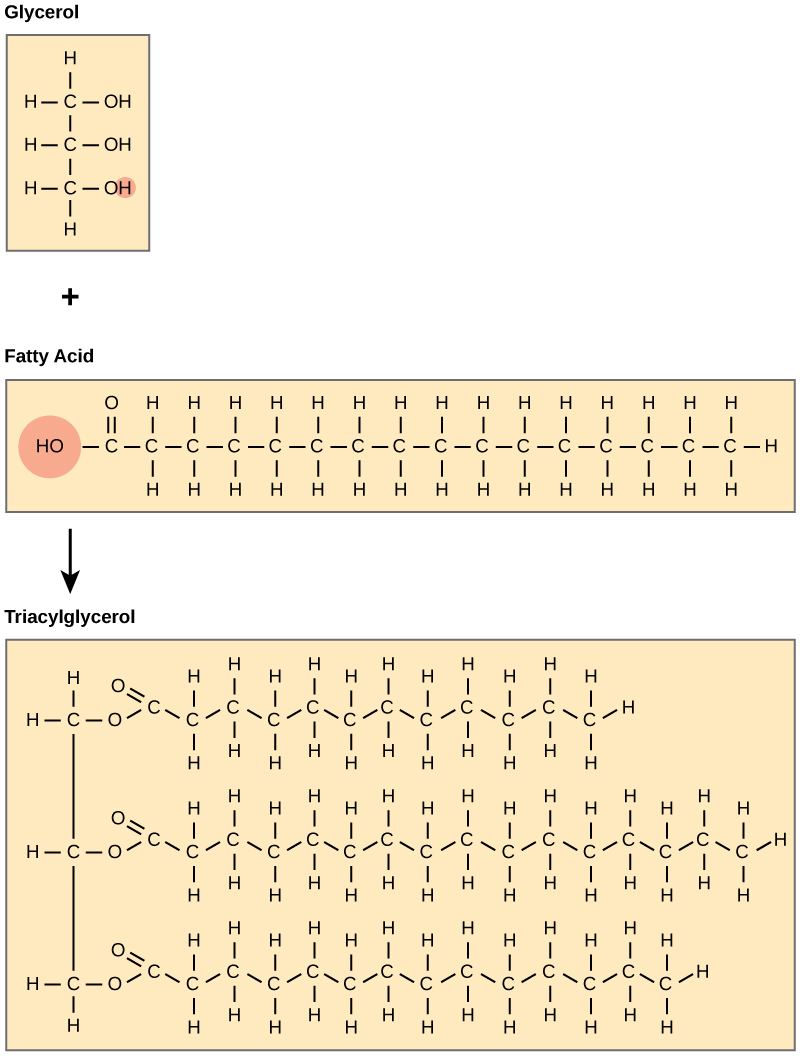

Figure 3.5.3. The figure illustrates the step-by-step assembly of a fat molecule. At the top left, a beige box shows glycerol, a three-carbon backbone with a hydroxyl (–OH) group on each carbon; one of these hydroxyls is circled to signal its reactivity. Beside it, a long beige rectangle depicts a fatty acid: a carboxyl group (HO–C=O) at the left end, its hydroxyl circled, followed by an extended zig-zag hydrocarbon chain of carbon and hydrogen atoms. A downward arrow leads to the larger bottom panel, labelled Triacylglycerol, where the glycerol and three identical fatty-acid chains have joined. Each former hydroxyl of glycerol is now linked to a fatty acid’s carbonyl carbon through an ester bond (highlighted in the drawing), and the three long hydrophobic tails hang parallel to one another. The layout visually explains that fat (triacylglycerol) forms via dehydration synthesis: glycerol’s three –OH groups and the –OH portions of three fatty-acid carboxyl groups lose water molecules and create three ester linkages, anchoring the fatty acids to the glycerol backbone. [Return to Figure 3.5.3]

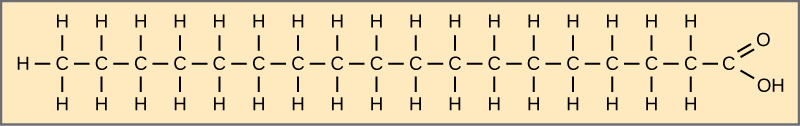

Figure 3.5.4. The diagram shows stearic acid as an extended zig-zag chain of eighteen carbon atoms drawn horizontally inside a beige rectangle. Each internal carbon is single-bonded to two hydrogens, while the leftmost carbon carries three hydrogens, illustrating complete saturation (no carbon–carbon double bonds). At the right end, the terminal carbon is double-bonded to an oxygen atom and single-bonded to a hydroxyl group (–OH), forming the molecule’s carboxyl (–COOH) head. This straight, fully hydrogenated chain exemplifies a common saturated fatty acid. [Return to Figure 3.5.4]

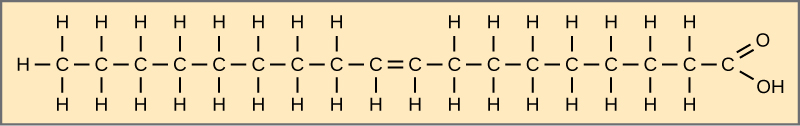

Figure 3.5.5. The figure depicts oleic acid as a horizontal zig-zag chain of eighteen carbon atoms inside a beige rectangle. Counting from the left, a single cis carbon–carbon double bond appears between carbons 9 and 10, introducing a slight bend; all other carbon–carbon links are single bonds. Each internal carbon bears two hydrogens, except the double-bonded pair, which each carry one hydrogen, while the leftmost carbon has three hydrogens. At the right end, the terminal carbon forms a carboxyl group (double-bonded to an oxygen and single-bonded to a hydroxyl group), creating the molecule’s hydrophilic head. This single double bond classifies oleic acid as a monounsaturated fatty acid, contrasting with fully saturated chains like stearic acid. [Return to Figure 3.5.5]

Figure 3.5.6. The figure stacks three beige panels to contrast fatty-acid geometries. The top panel shows stearic acid, an 18-carbon saturated chain with only single bonds and a linear, fully extended shape. The middle panel depicts cis-oleic acid, whose ninth–tenth carbon double bond places both highlighted hydrogens on the same side (marked by small pink circles), forcing the chain to kink at an angle. The bottom panel presents trans-oleic acid, identical in length and double-bond location but with the two highlighted hydrogens on opposite sides of the double bond, so the chain remains nearly straight. Together the images illustrate that saturated fatty acids lack double bonds, while unsaturated ones contain at least one; a cis double bond introduces a bend, whereas a trans double bond preserves a straight, stearic-acid-like conformation. [Return to Figure 3.5.6]

Figure 3.5.7. The image shows a close-up of a single elongated green leaf covered with water droplets. A small red ladybug with black spots is visible near the tip of the leaf on the right side. The green leaf is in sharp focus, emphasizing the texture of the surface and the smooth, spherical droplets of water. The background is a soft blur of green, suggesting more foliage in the surroundings, creating a serene, natural setting. [Return to Figure 3.5.7]

Figure 3.5.8. The illustration shows two steroid molecules, cholesterol on the left and cortisol on the right, each drawn as line-angle formulas on a beige background. Both share the hallmark steroid nucleus. a compact cluster of four fused hydrocarbon rings labeled A, B, C (three six-membered hexagons), and D (a five-membered pentagon). In cholesterol, the ring system bears a single hydroxyl (–OH) group at carbon 3, a small double bond between carbons 5 and 6, and an eight-carbon aliphatic tail extending from carbon 17 of ring D. Cortisol displays the same four-ring scaffold but is ornamented with multiple oxygen-containing groups: hydroxyls at carbons 11, 17, and 21, a carbonyl (=O) at carbon 3, and another carbonyl within a side chain at carbon 20. These additional polar moieties distinguish cortisol as a glucocorticoid hormone, whereas cholesterol remains largely non-polar, serving as a membrane component and precursor for other steroids. Together the two structures emphasize that all steroids consist of four fused hydrocarbon rings, with biological diversity arising from the functional groups attached around that common core. [Return to Figure 3.5.8]

Licenses and Attributions

“3.5 Lipid Structure Function” is adapted from “3.3 Lipids” by Mary Ann Clark, Matthew Douglas, and Jung Choi for OpenStax Biology 2e under CC-BY 4.0. “3.5 Lipid Structure Function” is licensed under CC-BY-NC 4.0.

Media Attributions

- Great Crested Grebe © Dr. Georg Wiestschorke is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- fat structure is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Stearic acid © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- oleic acid © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Trans fat © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Raindrops on a leaf © Denis Doukhan is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- steroids © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

macromolecules that is made up of fatty acids. Most lipids such as triglycerides are predominantly nonpolar and hydrophobic.

[latexpage]

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define species and describe how species are identified as different

- Describe genetic variables that lead to speciation

- Identify prezygotic and postzygotic reproductive barriers

- Explain allopatric and sympatric speciation

- Describe adaptive radiation

Although all life on earth shares various genetic similarities, only certain organisms combine genetic information by sexual reproduction and have offspring that can then successfully reproduce. Scientists call such organisms members of the same biological species.

Species and the Ability to Reproduce

A species is a group of individual organisms that interbreed and produce fertile, viable offspring. According to this definition, one species is distinguished from another when, in nature, it is not possible for matings between individuals from each species to produce fertile offspring.

Members of the same species share both external and internal characteristics, which develop from their DNA. The closer relationship two organisms share, the more DNA they have in common, just like people and their families. People’s DNA is likely to be more like their father or mother’s DNA than their cousin or grandparent’s DNA. Organisms of the same species have the highest level of DNA alignment and therefore share characteristics and behaviors that lead to successful reproduction.

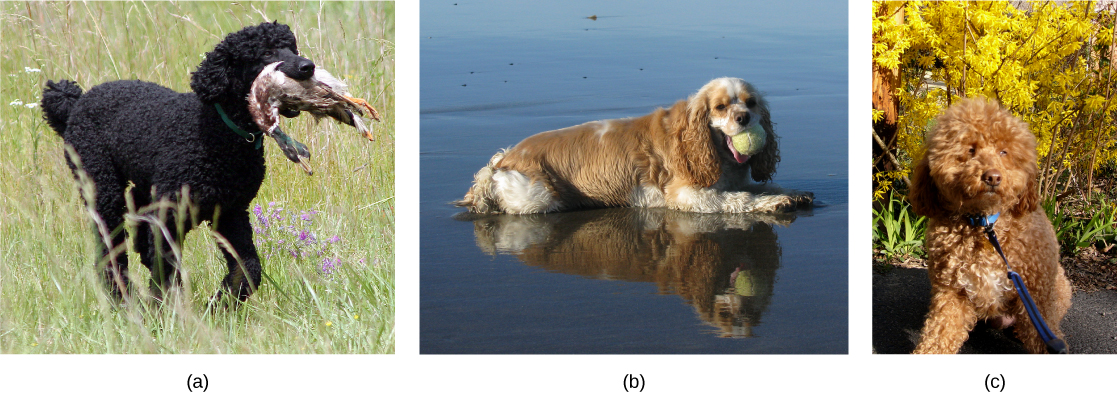

Species’ appearance can be misleading in suggesting an ability or inability to mate. For example, even though domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) display phenotypic differences, such as size, build, and coat, most dogs can interbreed and produce viable puppies that can mature and sexually reproduce ([link]).

In other cases, individuals may appear similar although they are not members of the same species. For example, even though bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and African fish eagles (Haliaeetus vocifer) are both birds and eagles, each belongs to a separate species group ([link]). If humans were to artificially intervene and fertilize the egg of a bald eagle with the sperm of an African fish eagle and a chick did hatch, that offspring, called a hybrid (a cross between two species), would probably be infertile—unable to successfully reproduce after it reached maturity. Different species may have different genes that are active in development; therefore, it may not be possible to develop a viable offspring with two different sets of directions. Thus, even though hybridization may take place, the two species still remain separate.

Populations of species share a gene pool: a collection of all the variants of genes in the species. Again, the basis to any changes in a group or population of organisms must be genetic for this is the only way to share and pass on traits. When variations occur within a species, they can only be passed to the next generation along two main pathways: asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction. The change will be passed on asexually simply if the reproducing cell possesses the changed trait. For the changed trait to be passed on by sexual reproduction, a gamete, such as a sperm or egg cell, must possess the changed trait. In other words, sexually-reproducing organisms can experience several genetic changes in their body cells, but if these changes do not occur in a sperm or egg cell, the changed trait will never reach the next generation. Only heritable traits can evolve. Therefore, reproduction plays a paramount role for genetic change to take root in a population or species. In short, organisms must be able to reproduce with each other to pass new traits to offspring.

Speciation

The biological definition of species, which works for sexually reproducing organisms, is a group of actually or potentially interbreeding individuals. There are exceptions to this rule. Many species are similar enough that hybrid offspring are possible and may often occur in nature, but for the majority of species this rule generally holds. In fact, the presence in nature of hybrids between similar species suggests that they may have descended from a single interbreeding species, and the speciation process may not yet be completed.

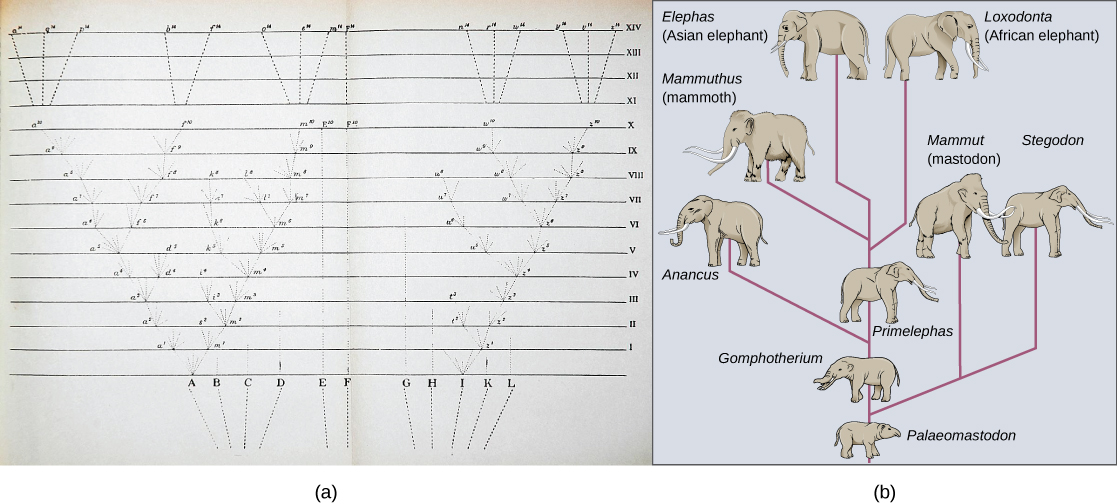

Given the extraordinary diversity of life on the planet there must be mechanisms for speciation: the formation of two species from one original species. Darwin envisioned this process as a branching event and diagrammed the process in the only illustration found in On the Origin of Species ([link]a). Compare this illustration to the diagram of elephant evolution ([link]b), which shows that as one species changes over time, it branches to form more than one new species, repeatedly, as long as the population survives or until the organism becomes extinct.

For speciation to occur, two new populations must be formed from one original population and they must evolve in such a way that it becomes impossible for individuals from the two new populations to interbreed. Biologists have proposed mechanisms by which this could occur that fall into two broad categories. Allopatric speciation (allo- = "other"; -patric = "homeland") involves geographic separation of populations from a parent species and subsequent evolution. Sympatric speciation (sym- = "same"; -patric = "homeland") involves speciation occurring within a parent species remaining in one location.

Biologists think of speciation events as the splitting of one ancestral species into two descendant species. There is no reason why there might not be more than two species formed at one time except that it is less likely and multiple events can be conceptualized as single splits occurring close in time.

Allopatric Speciation

A geographically continuous population has a gene pool that is relatively homogeneous. Gene flow, the movement of alleles across the range of the species, is relatively free because individuals can move and then mate with individuals in their new location. Thus, the frequency of an allele at one end of a distribution will be similar to the frequency of the allele at the other end. When populations become geographically discontinuous, that free-flow of alleles is prevented. When that separation lasts for a period of time, the two populations are able to evolve along different trajectories. Thus, their allele frequencies at numerous genetic loci gradually become more and more different as new alleles independently arise by mutation in each population. Typically, environmental conditions, such as climate, resources, predators, and competitors for the two populations will differ causing natural selection to favor divergent adaptations in each group.

Isolation of populations leading to allopatric speciation can occur in a variety of ways: a river forming a new branch, erosion forming a new valley, a group of organisms traveling to a new location without the ability to return, or seeds floating over the ocean to an island. The nature of the geographic separation necessary to isolate populations depends entirely on the biology of the organism and its potential for dispersal. If two flying insect populations took up residence in separate nearby valleys, chances are, individuals from each population would fly back and forth continuing gene flow. However, if two rodent populations became divided by the formation of a new lake, continued gene flow would be unlikely; therefore, speciation would be more likely.

Biologists group allopatric processes into two categories: dispersal and vicariance. Dispersal is when a few members of a species move to a new geographical area, and vicariance is when a natural situation arises to physically divide organisms.

Scientists have documented numerous cases of allopatric speciation taking place. For example, along the west coast of the United States, two separate sub-species of spotted owls exist. The northern spotted owl has genetic and phenotypic differences from its close relative: the Mexican spotted owl, which lives in the south ([link]).

Additionally, scientists have found that the further the distance between two groups that once were the same species, the more likely it is that speciation will occur. This seems logical because as the distance increases, the various environmental factors would likely have less in common than locations in close proximity. Consider the two owls: in the north, the climate is cooler than in the south; the types of organisms in each ecosystem differ, as do their behaviors and habits; also, the hunting habits and prey choices of the southern owls vary from the northern owls. These variances can lead to evolved differences in the owls, and speciation likely will occur.

Adaptive Radiation

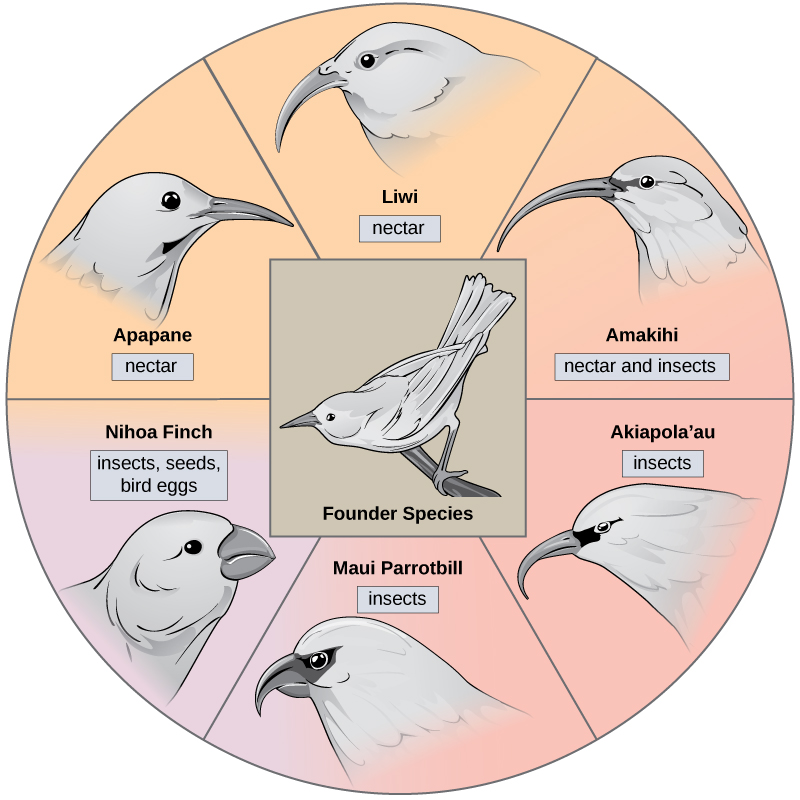

In some cases, a population of one species disperses throughout an area, and each finds a distinct niche or isolated habitat. Over time, the varied demands of their new lifestyles lead to multiple speciation events originating from a single species. This is called adaptive radiation because many adaptations evolve from a single point of origin; thus, causing the species to radiate into several new ones. Island archipelagos like the Hawaiian Islands provide an ideal context for adaptive radiation events because water surrounds each island which leads to geographical isolation for many organisms. The Hawaiian honeycreeper illustrates one example of adaptive radiation. From a single species, called the founder species, numerous species have evolved, including the six shown in [link].

Notice the differences in the species’ beaks in [link]. Evolution in response to natural selection based on specific food sources in each new habitat led to evolution of a different beak suited to the specific food source. The seed-eating bird has a thicker, stronger beak which is suited to break hard nuts. The nectar-eating birds have long beaks to dip into flowers to reach the nectar. The insect-eating birds have beaks like swords, appropriate for stabbing and impaling insects. Darwin’s finches are another example of adaptive radiation in an archipelago.

Click through this interactive site to see how island birds evolved in evolutionary increments from 5 million years ago to today.

Sympatric Speciation

Can divergence occur if no physical barriers are in place to separate individuals who continue to live and reproduce in the same habitat? The answer is yes. The process of speciation within the same space is called sympatric speciation; the prefix “sym” means same, so “sympatric” means “same homeland” in contrast to “allopatric” meaning “other homeland.” A number of mechanisms for sympatric speciation have been proposed and studied.

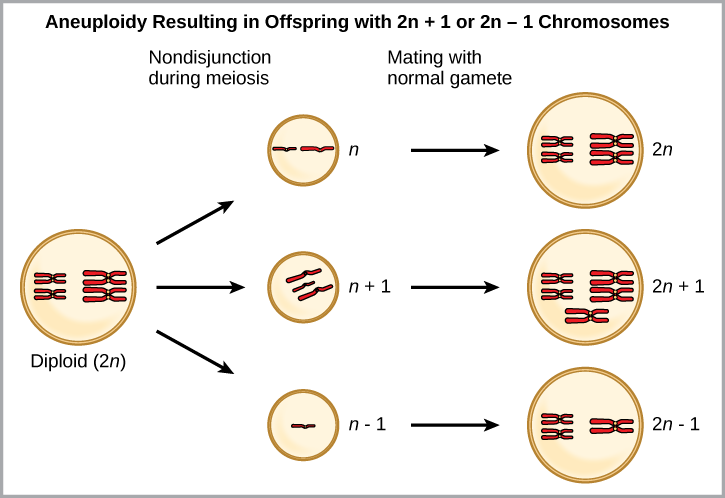

One form of sympatric speciation can begin with a serious chromosomal error during cell division. In a normal cell division event chromosomes replicate, pair up, and then separate so that each new cell has the same number of chromosomes. However, sometimes the pairs separate and the end cell product has too many or too few individual chromosomes in a condition called aneuploidy ([link]).

Which is most likely to survive, offspring with 2n+1 chromosomes or offspring with 2n-1 chromosomes?

<!--<para>Loss of genetic material is almost always lethal, so offspring with 2n+1 chromosomes are more likely to survive.-->

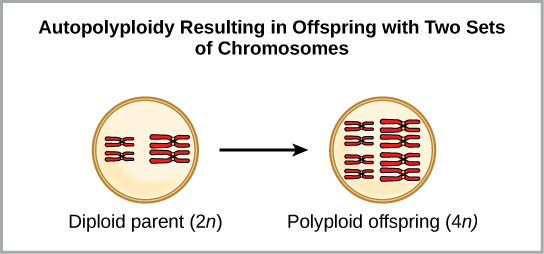

Polyploidy is a condition in which a cell or organism has an extra set, or sets, of chromosomes. Scientists have identified two main types of polyploidy that can lead to reproductive isolation of an individual in the polyploidy state. Reproductive isolation is the inability to interbreed. In some cases, a polyploid individual will have two or more complete sets of chromosomes from its own species in a condition called autopolyploidy ([link]). The prefix “auto-” means “self,” so the term means multiple chromosomes from one’s own species. Polyploidy results from an error in meiosis in which all of the chromosomes move into one cell instead of separating.

For example, if a plant species with 2n = 6 produces autopolyploid gametes that are also diploid (2n = 6, when they should be n = 3), the gametes now have twice as many chromosomes as they should have. These new gametes will be incompatible with the normal gametes produced by this plant species. However, they could either self-pollinate or reproduce with other autopolyploid plants with gametes having the same diploid number. In this way, sympatric speciation can occur quickly by forming offspring with 4n called a tetraploid. These individuals would immediately be able to reproduce only with those of this new kind and not those of the ancestral species.

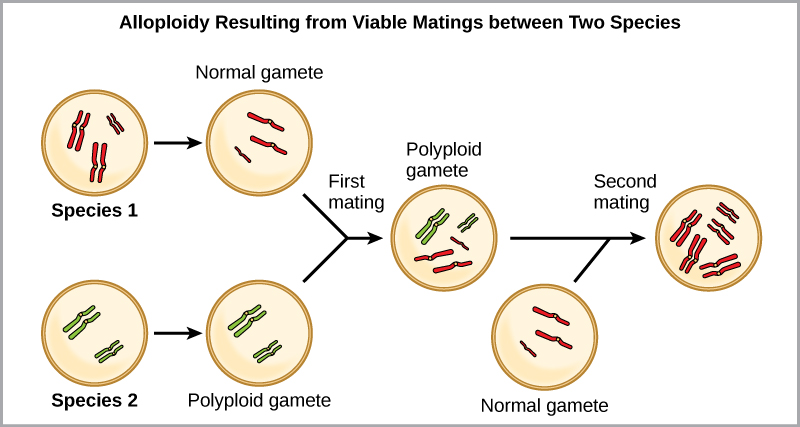

The other form of polyploidy occurs when individuals of two different species reproduce to form a viable offspring called an allopolyploid. The prefix “allo-” means “other” (recall from allopatric): therefore, an allopolyploid occurs when gametes from two different species combine. [link] illustrates one possible way an allopolyploid can form. Notice how it takes two generations, or two reproductive acts, before the viable fertile hybrid results.

The cultivated forms of wheat, cotton, and tobacco plants are all allopolyploids. Although polyploidy occurs occasionally in animals, it takes place most commonly in plants. (Animals with any of the types of chromosomal aberrations described here are unlikely to survive and produce normal offspring.) Scientists have discovered more than half of all plant species studied relate back to a species evolved through polyploidy. With such a high rate of polyploidy in plants, some scientists hypothesize that this mechanism takes place more as an adaptation than as an error.

Reproductive Isolation

Given enough time, the genetic and phenotypic divergence between populations will affect characters that influence reproduction: if individuals of the two populations were to be brought together, mating would be less likely, but if mating occurred, offspring would be non-viable or infertile. Many types of diverging characters may affect the reproductive isolation, the ability to interbreed, of the two populations.

Reproductive isolation can take place in a variety of ways. Scientists organize them into two groups: prezygotic barriers and postzygotic barriers. Recall that a zygote is a fertilized egg: the first cell of the development of an organism that reproduces sexually. Therefore, a prezygotic barrier is a mechanism that blocks reproduction from taking place; this includes barriers that prevent fertilization when organisms attempt reproduction. A postzygotic barrier occurs after zygote formation; this includes organisms that don’t survive the embryonic stage and those that are born sterile.

Some types of prezygotic barriers prevent reproduction entirely. Many organisms only reproduce at certain times of the year, often just annually. Differences in breeding schedules, called temporal isolation, can act as a form of reproductive isolation. For example, two species of frogs inhabit the same area, but one reproduces from January to March, whereas the other reproduces from March to May ([link]).

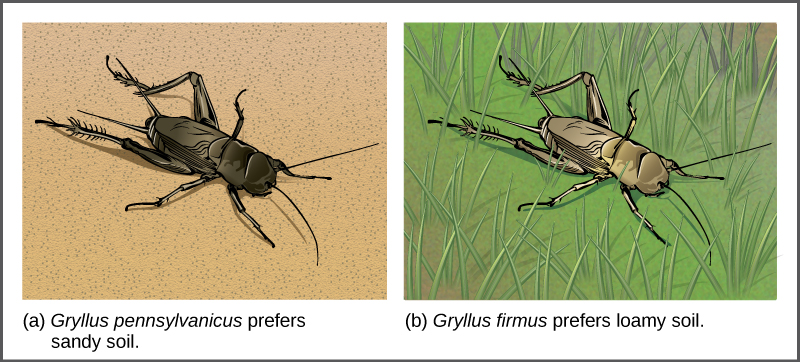

In some cases, populations of a species move or are moved to a new habitat and take up residence in a place that no longer overlaps with the other populations of the same species. This situation is called habitat isolation. Reproduction with the parent species ceases, and a new group exists that is now reproductively and genetically independent. For example, a cricket population that was divided after a flood could no longer interact with each other. Over time, the forces of natural selection, mutation, and genetic drift will likely result in the divergence of the two groups ([link]).

Behavioral isolation occurs when the presence or absence of a specific behavior prevents reproduction from taking place. For example, male fireflies use specific light patterns to attract females. Various species of fireflies display their lights differently. If a male of one species tried to attract the female of another, she would not recognize the light pattern and would not mate with the male.

Other prezygotic barriers work when differences in their gamete cells (eggs and sperm) prevent fertilization from taking place; this is called a gametic barrier. Similarly, in some cases closely related organisms try to mate, but their reproductive structures simply do not fit together. For example, damselfly males of different species have differently shaped reproductive organs. If one species tries to mate with the female of another, their body parts simply do not fit together. ([link]).

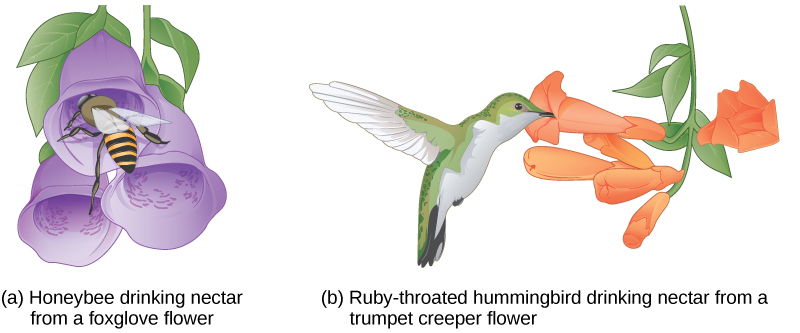

In plants, certain structures aimed to attract one type of pollinator simultaneously prevent a different pollinator from accessing the pollen. The tunnel through which an animal must access nectar can vary widely in length and diameter, which prevents the plant from being cross-pollinated with a different species ([link]).

When fertilization takes place and a zygote forms, postzygotic barriers can prevent reproduction. Hybrid individuals in many cases cannot form normally in the womb and simply do not survive past the embryonic stages. This is called hybrid inviability because the hybrid organisms simply are not viable. In another postzygotic situation, reproduction leads to the birth and growth of a hybrid that is sterile and unable to reproduce offspring of their own; this is called hybrid sterility.

Habitat Influence on Speciation

Sympatric speciation may also take place in ways other than polyploidy. For example, consider a species of fish that lives in a lake. As the population grows, competition for food also grows. Under pressure to find food, suppose that a group of these fish had the genetic flexibility to discover and feed off another resource that was unused by the other fish. What if this new food source was found at a different depth of the lake? Over time, those feeding on the second food source would interact more with each other than the other fish; therefore, they would breed together as well. Offspring of these fish would likely behave as their parents: feeding and living in the same area and keeping separate from the original population. If this group of fish continued to remain separate from the first population, eventually sympatric speciation might occur as more genetic differences accumulated between them.

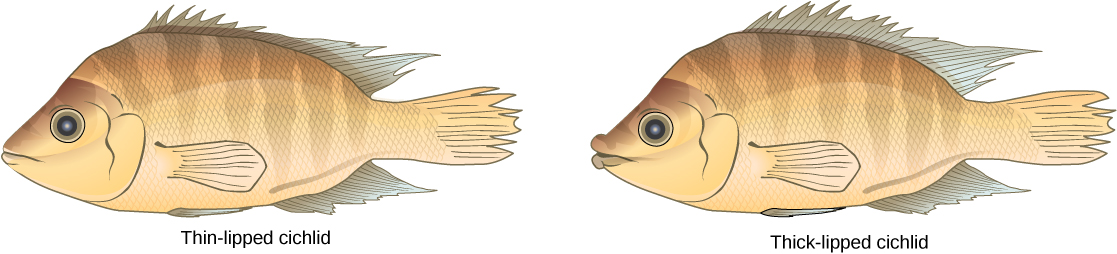

This scenario does play out in nature, as do others that lead to reproductive isolation. One such place is Lake Victoria in Africa, famous for its sympatric speciation of cichlid fish. Researchers have found hundreds of sympatric speciation events in these fish, which have not only happened in great number, but also over a short period of time. [link] shows this type of speciation among a cichlid fish population in Nicaragua. In this locale, two types of cichlids live in the same geographic location but have come to have different morphologies that allow them to eat various food sources.

Section Summary

Speciation occurs along two main pathways: geographic separation (allopatric speciation) and through mechanisms that occur within a shared habitat (sympatric speciation). Both pathways isolate a population reproductively in some form. Mechanisms of reproductive isolation act as barriers between closely related species, enabling them to diverge and exist as genetically independent species. Prezygotic barriers block reproduction prior to formation of a zygote, whereas postzygotic barriers block reproduction after fertilization occurs. For a new species to develop, something must cause a breach in the reproductive barriers. Sympatric speciation can occur through errors in meiosis that form gametes with extra chromosomes (polyploidy). Autopolyploidy occurs within a single species, whereas allopolyploidy occurs between closely related species.

Art Connections

Review Questions

Which situation would most likely lead to allopatric speciation?

- flood causes the formation of a new lake.

- A storm causes several large trees to fall down.

- A mutation causes a new trait to develop.

- An injury causes an organism to seek out a new food source.

A

What is the main difference between dispersal and vicariance?

- One leads to allopatric speciation, whereas the other leads to sympatric speciation.

- One involves the movement of the organism, and the other involves a change in the environment.

- One depends on a genetic mutation occurring, and the other does not.

- One involves closely related organisms, and the other involves only individuals of the same species.

B

Which variable increases the likelihood of allopatric speciation taking place more quickly?

- lower rate of mutation

- longer distance between divided groups

- increased instances of hybrid formation

- equivalent numbers of individuals in each population

B

What is the main difference between autopolyploid and allopolyploid?

- the number of chromosomes

- the functionality of the chromosomes

- the source of the extra chromosomes

- the number of mutations in the extra chromosomes

C

Which reproductive combination produces hybrids?

- when individuals of the same species in different geographical areas reproduce

- when any two individuals sharing the same habitat reproduce

- when members of closely related species reproduce

- when offspring of the same parents reproduce

C

Which condition is the basis for a species to be reproductively isolated from other members?

- It does not share its habitat with related species.

- It does not exist out of a single habitat.

- It does not exchange genetic information with other species.

- It does not undergo evolutionary changes for a significant period of time.

C

Which situation is not an example of a prezygotic barrier?

- Two species of turtles breed at different times of the year.

- Two species of flowers attract different pollinators.

- Two species of birds display different mating dances.

- Two species of insects produce infertile offspring.

D

Free Response

Why do island chains provide ideal conditions for adaptive radiation to occur?

Organisms of one species can arrive to an island together and then disperse throughout the chain, each settling into different niches and exploiting different food resources to reduce competition.

Two species of fish had recently undergone sympatric speciation. The males of each species had a different coloring through which the females could identify and choose a partner from her own species. After some time, pollution made the lake so cloudy that it was hard for females to distinguish colors. What might take place in this situation?

It is likely the two species would start to reproduce with each other. Depending on the viability of their offspring, they may fuse back into one species.

Why can polyploidy individuals lead to speciation fairly quickly?

The formation of gametes with new n numbers can occur in one generation. After a couple of generations, enough of these new hybrids can form to reproduce together as a new species.

Glossary

- adaptive radiation

- speciation when one species radiates out to form several other species

- allopatric speciation

- speciation that occurs via geographic separation

- allopolyploid

- polyploidy formed between two related, but separate species

- aneuploidy

- condition of a cell having an extra chromosome or missing a chromosome for its species

- autopolyploid

- polyploidy formed within a single species

- behavioral isolation

- type of reproductive isolation that occurs when a specific behavior or lack of one prevents reproduction from taking place

- dispersal

- allopatric speciation that occurs when a few members of a species move to a new geographical area

- gametic barrier

- prezygotic barrier occurring when closely related individuals of different species mate, but differences in their gamete cells (eggs and sperm) prevent fertilization from taking place

- habitat isolation

- reproductive isolation resulting when populations of a species move or are moved to a new habitat, taking up residence in a place that no longer overlaps with the other populations of the same species

- hybrid

- offspring of two closely related individuals, not of the same species

- postzygotic barrier

- reproductive isolation mechanism that occurs after zygote formation

- prezygotic barrier

- reproductive isolation mechanism that occurs before zygote formation

- reproductive isolation

- situation that occurs when a species is reproductively independent from other species; this may be brought about by behavior, location, or reproductive barriers

- speciation

- formation of a new species

- species

- group of populations that interbreed and produce fertile offspring

- sympatric speciation

- speciation that occurs in the same geographic space

- temporal isolation

- differences in breeding schedules that can act as a form of prezygotic barrier leading to reproductive isolation

- vicariance

- allopatric speciation that occurs when something in the environment separates organisms of the same species into separate groups

organic compound (alcohol) with three carbons, five hydrogens, and three hydroxyl (OH) groups

ong chain of hydrocarbons to which a carboxyl group is attached

the acidic functional group made of a carbon double-bonded to one oxygen and single-bonded to a hydroxyl (–OH), written –COOH in condensed form.

fat molecule; consists of three fatty acids linked to a glycerol molecule

long-chain hydrocarbon that has one or more double bonds in the hydrocarbon chain

fat formed artificially by hydrogenating oils, leading to a different arrangement of double bond(s) than those in naturally occurring lipids

cell membranes' major constituent; comprised of two fatty acids and a phosphate-containing group attached to a glycerol backbone

having both hydrophilic and hydrophobic parts.

molecule that does not have the ability to bond with water; “water-hating”

molecule with the ability to interact with water; “water-loving”

type of lipid comprised of four fused hydrocarbon rings forming a planar structure

a functional group “which consists of an –OH (oxygen-hydrogen) attached to a carbon chain” and is polar

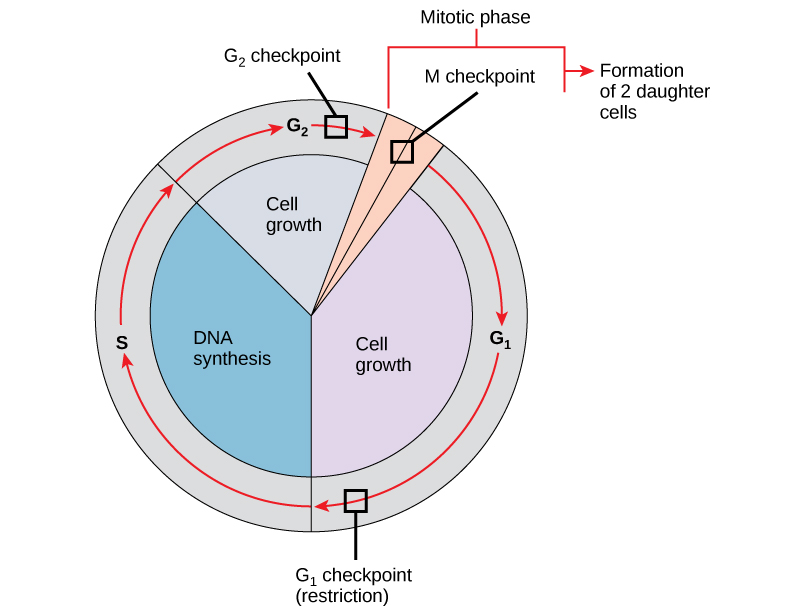

It is essential that daughter cells be exact duplicates of the parent cell. Mistakes in the duplication or distribution of the chromosomes lead to mutations that may be passed forward to every new cell produced from the abnormal cell. To prevent a compromised cell from continuing to divide, there are internal control mechanisms that operate at three main cell cycle checkpoints at which the cell cycle can be stopped until conditions are favorable.

The first checkpoint (G1) determines whether all conditions are favorable for cell division to proceed. This checkpoint is the point at which the cell irreversibly commits to the cell-division process. In addition to adequate reserves and cell size, there is a check for damage to the genomic DNA. A cell that does not meet all the requirements will not be released into the S phase.

The second checkpoint (G2) bars the entry to the mitotic phase if certain conditions are not met. The most important role of this checkpoint is to ensure that all of the chromosomes have been replicated and that the replicated DNA is not damaged.

The final checkpoint (M) occurs in the middle of mitosis. This checkpoint determines if all of the copied chromosomes are arranged appropriately to be separated to opposite sides of the cell. If this doesn’t happen correctly, incorrect numbers of chromosomes can be partitioned into each of the daughter cells, which would likely cause them to die.

Regulator Molecules of the Cell Cycle

In addition to the internally controlled checkpoints, there are two groups of intracellular molecules that regulate the cell cycle. These regulatory molecules either promote progress of the cell to the next phase (positive regulation) or halt the cycle (negative regulation). Regulator molecules may act individually, or they can influence the activity or production of other regulatory proteins. Therefore, it is possible that the failure of a single regulator may have almost no effect on the cell cycle, especially if more than one mechanism controls the same event. It is also possible that the effect of a deficient or non-functioning regulator can be wide-ranging and possibly fatal to the cell if multiple processes are affected.

Positive Regulation of the Cell Cycle

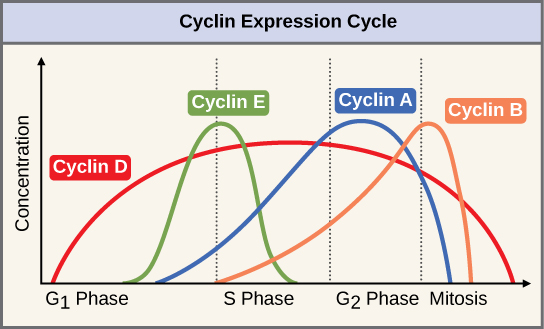

Two groups of proteins, called cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks), are responsible for the progress of the cell through the various checkpoints. The levels of the four cyclin proteins fluctuate throughout the cell cycle in a predictable pattern (Figure 2). Increases in the concentration of cyclin proteins are triggered by both external and internal signals. After the cell moves to the next stage of the cell cycle, the cyclins that were active in the previous stage are degraded.

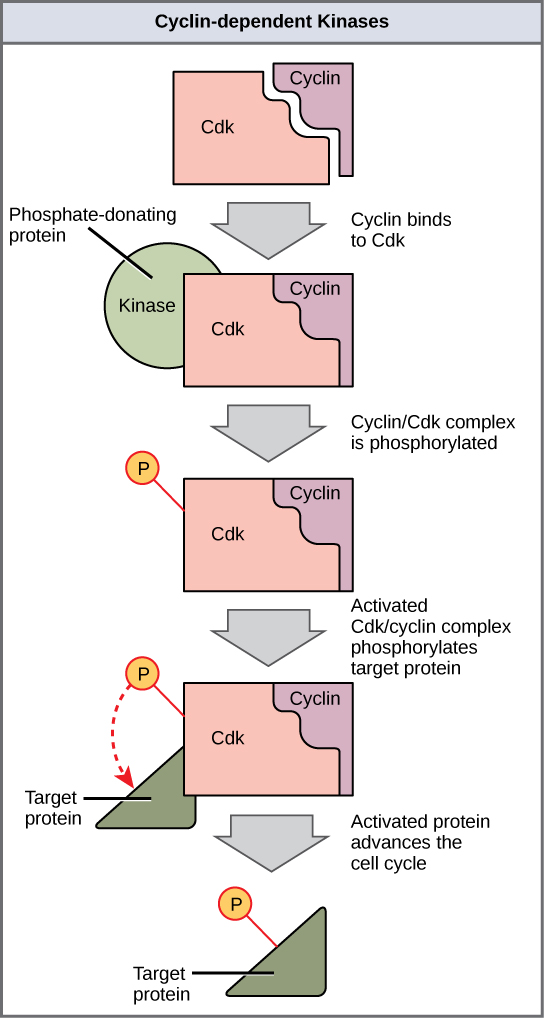

Cyclins regulate the cell cycle only when they are tightly bound to Cdks. To be fully active, the Cdk/cyclin complex must also be phosphorylated in specific locations. Like all kinases, Cdks are enzymes (kinases) that phosphorylate other proteins. Phosphorylation activates the protein by changing its shape. The proteins phosphorylated by Cdks are involved in advancing the cell to the next phase (Figure 3). The levels of Cdk proteins are relatively stable throughout the cell cycle; however, the concentrations of cyclin fluctuate and determine when Cdk/cyclin complexes form. The different cyclins and Cdks bind at specific points in the cell cycle and thus regulate different checkpoints.

Since the cyclic fluctuations of cyclin levels are based on the timing of the cell cycle and not on specific events, regulation of the cell cycle usually occurs by either the Cdk molecules alone or the Cdk/cyclin complexes. Without a specific concentration of fully activated cyclin/Cdk complexes, the cell cycle cannot proceed through the checkpoints.

Negative Regulation of the Cell Cycle

The second group of cell cycle regulatory molecules are negative regulators. In positive regulation, active molecules such as CDK/cyclin complexes cause the cell cycle to progress. In negative regulation, active molecules halt the cell cycle.

The best understood negative regulatory molecules are retinoblastoma protein (Rb), p53, and p21. Much of what is known about cell cycle regulation comes from research conducted with cells that have lost regulatory control. All three of these regulatory proteins were discovered to be damaged or non-functional in cells that had begun to replicate uncontrollably (became cancerous). In each case, the main cause of the unchecked progress through the cell cycle was a faulty copy of the regulatory protein. For this reason, Rb and other proteins that negatively regulate the cell cycle are sometimes called tumor suppressors.

Rb, p53, and p21 act primarily at the G1 checkpoint. p53 is a multi-functional protein that has a major impact on the commitment of a cell to division because it acts when there is damaged DNA in cells that are undergoing the preparatory processes during G1. If damaged DNA is detected, p53 halts the cell cycle and recruits enzymes to repair the DNA. If the DNA cannot be repaired, p53 can trigger apoptosis, or cell suicide, to prevent the duplication of damaged chromosomes. As p53 levels rise, the production of p21 is triggered. p21 enforces the halt in the cycle dictated by p53 by binding to and inhibiting the activity of the Cdk/cyclin complexes. As a cell is exposed to more stress, higher levels of p53 and p21 accumulate, making it less likely that the cell will move into the S phase.

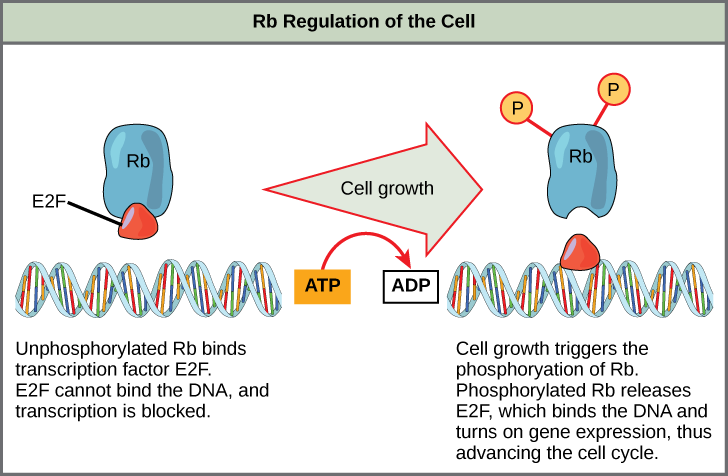

Rb exerts its regulatory influence on other positive regulator proteins. Chiefly, Rb monitors cell size. In the active, dephosphorylated state, Rb binds to proteins called transcription factors (Figure 4). Transcription factors “turn on” specific genes, allowing the production of proteins encoded by that gene. When Rb is bound to transcription factors, production of proteins necessary for the G1/S transition is blocked. As the cell increases in size, Rb is slowly phosphorylated until it becomes inactivated. Rb releases the transcription factors, which can now turn on the gene that produces the transition protein, and this particular block is removed. For the cell to move past each of the checkpoints, all positive regulators must be “turned on,” and all negative regulators must be “turned off.”

References

Unless otherwise noted, images on this page are licensed under CC-BY 4.0 by OpenStax.

OpenStax, Biology. OpenStax CNX. May 27, 2016 http://cnx.org/contents/s8Hh0oOc@9.10:Vbi92lHB@9/The-Cell-Cycle

OpenStax, Biology. OpenStax CNX. May 27, 2016 http://cnx.org/contents/s8Hh0oOc@9.10:LlKfCy5H@4/Prokaryotic-Cell-Division