14.4 mRNA Processing

Elizabeth Dahlhoff

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe the different steps in RNA processing.

- Explain the significance of exons, introns, and splicing.

mRNA Processing

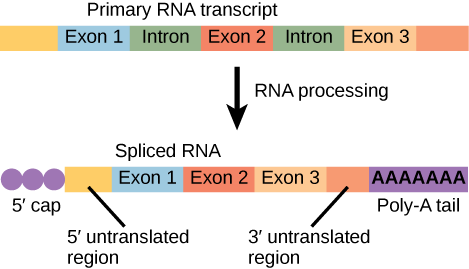

After transcription, eukaryotic pre-mRNA undergoes extensive processing before it is ready to be translated. Eukaryotic protein-coding sequences are not continuous, as they are in prokaryotes. The coding sequence exons are interrupted by noncoding introns, which must be removed to make a translatable mRNA. The additional steps involved in eukaryotic mRNA maturation also create a molecule with a much longer half-life than a prokaryotic mRNA. Eukaryotic mRNAs last for several hours, whereas the typical E. coli mRNA lasts no more than five seconds.

Pre-mRNAs are first coated in RNA-stabilizing proteins; these protect the pre-mRNA from degradation while it is processed and exported out of the nucleus. The three most important steps of pre-mRNA processing are the addition of stabilizing and signaling factors at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the molecule, and the removal of the introns.

5′ Capping

While the pre-mRNA is still being synthesized, a 7-methylguanosine cap, also called the 5' cap, is added to the 5′ end of the growing transcript by a phosphate linkage. This functional group protects the nascent mRNA from degradation. In addition, factors involved in protein synthesis recognize the cap to help initiate translation by ribosomes.

3′ Poly-A Tail

Once elongation is complete, the pre-mRNA is cleaved by an endonuclease between an AAUAAA consensus sequence and a GU-rich sequence, leaving the AAUAAA sequence on the pre-mRNA. An enzyme called poly-A polymerase then adds a string of approximately 200 A residues, called the poly-A tail. This modification further protects the pre-mRNA from degradation and is also the binding site for a protein necessary for exporting the processed mRNA to the cytoplasm.

RNA Editing in organelles

Other editing may occur in mRNA. Virtually all eukaryotes have organelles called mitochondria that supply the cell with chemical energy. Mitochondria are organelles that express their own DNA and are believed to be the remnants of a symbiotic relationship between a eukaryote and an engulfed prokaryote. Some genes in the mitochondrial genome encode 40- to 80-nucleotide guide RNAs. One or more of these molecules interacts by complementary base pairing with some of the nucleotides in the pre-mRNA transcript. However, the guide RNA has more A nucleotides than the pre-mRNA has U nucleotides to bind with. In these regions, the guide RNA loops out. The 3′ ends of guide RNAs have a long poly-U tail, and these U bases are inserted in regions of the pre-mRNA transcript at which the guide RNAs are looped. This process is entirely mediated by RNA molecules. That is, guide RNAs—rather than proteins—serve as the catalysts in RNA editing.

In the mitochondria of some plants, almost all pre-mRNAs are edited. RNA editing has also been identified in mammals such as rats, rabbits, and even humans. What could be the evolutionary reason for this additional step in pre-mRNA processing? One possibility is that the mitochondria, being remnants of ancient prokaryotes, have an equally ancient RNA-based method for regulating gene expression. In support of this hypothesis, edits made to pre-mRNAs differ depending on cellular conditions. Although speculative, the process of RNA editing may be a holdover from a primordial time when RNA molecules, instead of proteins, were responsible for catalyzing reactions.

Pre-mRNA Splicing

Eukaryotic genes are composed of exons, which correspond to protein-coding sequences (ex-on signifies that they are expressed), and intervening sequences called introns (int-ron denotes their intervening role), which may be involved in gene regulation but are removed from the pre-mRNA during processing. Intron sequences in mRNA do not encode functional proteins.

The discovery of introns came as a surprise to researchers in the 1970s who expected that pre-mRNAs would specify protein sequences without further processing, as they had observed in prokaryotes. The genes of higher eukaryotes very often contain one or more introns. These regions may correspond to regulatory sequences; however, the biological significance of having many introns or having very long introns in a gene is unclear. It is possible that introns slow down gene expression because it takes longer to transcribe pre-mRNAs with lots of introns. Alternatively, introns may be nonfunctional sequence remnants left over from the fusion of ancient genes throughout the course of evolution. This is supported by the fact that separate exons often encode separate protein subunits or domains. For the most part, the sequences of introns can be mutated without ultimately affecting the protein product.

All of a pre-mRNA’s introns must be completely and precisely removed before protein synthesis. If the process errs by even a single nucleotide, the reading frame of the rejoined exons would shift, and the resulting protein would be dysfunctional. The process of removing introns and reconnecting exons is called splicing. Introns are removed and degraded while the pre-mRNA is still in the nucleus. Splicing occurs by a sequence-specific mechanism that ensures introns will be removed and exons rejoined with the accuracy and precision of a single nucleotide. Although the intron itself is noncoding, the beginning and end of each intron is marked with specific nucleotides: GU at the 5′ end and AG at the 3′ end of the intron. The splicing of pre-mRNAs is conducted by complexes of proteins and RNA molecules called spliceosomes.

Note that more than 70 individual introns can be present, and each has to undergo the process of splicing—in addition to 5′ capping and the addition of a poly-A tail—just to generate a single, translatable mRNA molecule. RNA splicing is visualized nicely in the animation below (Video 14.4.1).

Video 14.4.1. RNA Splicing by DNA Learning Center

Practice Questions

Section Summary

Eukaryotic pre-mRNAs are modified with a 5′ methylguanosine cap and a poly-A tail. These structures protect the mature mRNA from degradation and help export it from the nucleus. Pre-mRNAs also undergo splicing, in which introns are removed and exons are reconnected with single-nucleotide accuracy. Only finished mRNAs that have undergone 5′ capping, 3′ polyadenylation, and intron splicing are exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Rarely, RNA editing is also performed to insert missing bases after an mRNA has been synthesized.

Glossary

- 7-methylguanosine cap

- modification added to the 5′ end of pre-mRNAs to protect mRNA from degradation and assist translation

- anticodon

- three-nucleotide sequence in a tRNA molecule that corresponds to an mRNA codon

- exon

- sequence present in protein-coding mRNA after completion of pre-mRNA splicing

- intron

- non–protein-coding intervening sequences that are spliced from mRNA during processing

- poly-A tail

- modification added to the 3′ end of pre-mRNAs to protect mRNA from degradation and assist mRNA export from the nucleus

- RNA editing

- direct alteration of one or more nucleotides in an mRNA that has already been synthesized

- splicing

- process of removing introns and reconnecting exons in a pre-mRNA

Figure Description

Figure 14.4.1. The image shows two stages of eukaryotic mRNA. The top illustrates a primary RNA transcript containing three exons (labeled Exon 1, Exon 2, Exon 3) separated by two introns. The bottom illustrates the mature mRNA after processing, with a 5′ cap on the left, the introns removed so the exons are joined together, and a long poly-A tail represented by repeated “A” symbols on the right end. [Return to Figure 14.4.1]

Licenses and Attributions

Media Attributions

- mrna processing © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

a methylated guanosine triphosphate (GTP) molecule that is attached to the 5' end of a messenger RNA to protect the end from degradation

modification added to the 3' end of pre-mRNAs to protect mRNA from degradation and assist mRNA export from the nucleus