7.3 Photosynthesis: Light-Dependent Reactions

Christelle Sabatier

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Explain how plants absorb energy from sunlight.

- Describe how and where photosynthesis takes place within a plant.

How can light energy be used to make food? When a person turns on a lamp, electrical energy becomes light energy. Like all other forms of kinetic energy, light can travel, change form, and be harnessed to do work. In the case of photosynthesis, light energy is converted into chemical energy, which photoautotrophs use to build basic carbohydrate molecules.

Absorption of Light

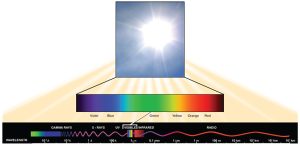

Visible light constitutes only one of many types of electromagnetic radiation emitted from the sun and other stars. Scientists differentiate the various types of radiant energy from the sun within the electromagnetic spectrum. The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of all possible frequencies of radiation (Figure 7.3.1). The difference between wavelengths relates to the amount of energy carried by them.

Each type of electromagnetic radiation travels at a particular wavelength. The longer the wavelength, the less energy it carries. Short, tight waves carry the most energy. This may seem illogical, but think of it in terms of a piece of moving heavy rope. It takes little effort by a person to move a rope in long, wide waves. To make a rope move in short, tight waves, a person would need to apply significantly more energy.

The electromagnetic spectrum (Figure 7.3.1) shows several types of electromagnetic radiation originating from the sun, including X-rays and ultraviolet (UV) rays. The higher-energy waves can penetrate tissues and damage cells and DNA, which explains why both X-rays and UV rays can be harmful to living organisms.

Light energy initiates the process of photosynthesis when pigments absorb specific wavelengths of visible light. Organic pigments, whether in the human retina or the chloroplast thylakoid, have a narrow range of energy levels that they can absorb. In plants, pigment molecules absorb only light in the wavelength range of 700 nm to 400 nm; plant physiologists refer to this range for plants as photosynthetically active radiation. Light energy can excite electrons. When a photon of light energy interacts with an electron, the electron may absorb the energy and jump from its lowest energy ground state to an excited state.

How Light-Dependent Reactions Work

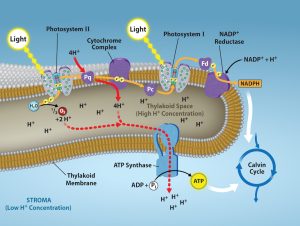

The overall function of light-dependent reactions is to convert solar energy into chemical energy in the form of NADPH and ATP. This chemical energy supports the light-independent reactions and fuels the assembly of sugar molecules. Protein complexes and pigment molecules work together to produce NADPH and ATP. The numbering of the photosystems is derived from the order in which they were discovered, not in the order of the transfer of electrons.

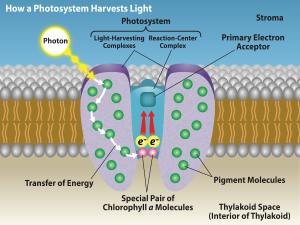

The actual step that converts light energy into chemical energy takes place in a multiprotein complex called a photosystem, two types of which are found embedded in the thylakoid membrane: photosystem II (PSII) and photosystem I (PSI) (Figure 7.3.2). The two complexes differ on the basis of what they oxidize (that is, the source of the low-energy electron supply) and what they reduce (the place to which they deliver their energized electrons).

Both photosystems have the same basic structure; a number of antenna proteins to which the chlorophyll molecules are bound surround the reaction center where the photochemistry takes place. Each photosystem is serviced by the light-harvesting complex, which passes energy from sunlight to the reaction center; it consists of multiple antenna proteins that contain a mixture of 300 to 400 chlorophyll a and b molecules as well as other pigments like carotenoids. The absorption of a single photon or distinct quantity or “packet” of light by any of the chlorophylls pushes that molecule into an excited state. In short, the light energy has now been captured by biological molecules but is not stored in any useful form yet. The energy is transferred from chlorophyll to chlorophyll until eventually (after about a millionth of a second), it is delivered to the reaction center. Up to this point, only energy has been transferred between molecules, not electrons.

Understanding Pigments

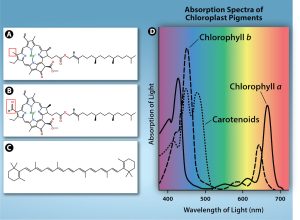

Different kinds of pigments exist, and each absorbs only specific wavelengths (colors) of visible light. Pigments reflect or transmit the wavelengths they cannot absorb, making them appear a mixture of the reflected or transmitted light colors.

Chlorophylls and carotenoids are the two major classes of photosynthetic pigments found in plants and algae; each class has multiple types of pigment molecules. There are five major chlorophylls: a, b, c, and d and a related molecule found in prokaryotes called bacteriochlorophyll. Chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b are found in higher plant chloroplasts.

In photosynthesis, carotenoids function as photosynthetic pigments that are very efficient molecules for the disposal of excess energy. When a leaf is exposed to full sun, the light-dependent reactions are required to process an enormous amount of energy; if that energy is not handled properly, it can do significant damage. Therefore, many carotenoids reside in the thylakoid membrane, absorb excess energy, and safely dissipate that energy as heat.

Each type of pigment can be identified by the specific pattern of wavelengths it absorbs from visible light: This is termed the absorption spectrum. The graph in Figure 7.3.3 shows the absorption spectra for chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and a type of carotenoid pigment called β-carotene (which absorbs blue and green light). Notice how each pigment has a distinct set of peaks and troughs, revealing a highly specific pattern of absorption. Chlorophyll a absorbs wavelengths from either end of the visible spectrum (blue and red), but not green. Because green is reflected or transmitted, chlorophyll appears green. Carotenoids absorb in the short-wavelength blue region, and reflect the longer yellow, red, and orange wavelengths.

The reaction center contains a pair of chlorophyll a molecules with a special property. Those two chlorophylls can undergo oxidation upon excitation; they can actually give up an electron. It is at this step in the reaction center during photosynthesis that light energy is converted into an excited electron. All of the subsequent steps involve getting that electron onto the energy carrier NADPH for delivery to the Calvin cycle where the electron is deposited onto carbon for long-term storage in the form of a carbohydrate. The cytochrome complex, an enzyme composed of two protein complexes, enables both the transfer of protons across the thylakoid membrane and the transfer of electrons from PSII to PSI.

The reaction center of PSII delivers its high-energy electrons, one at the time, to the primary electron acceptor, and through the electron transport chain to PSI (Figure 7.3.4). The reaction center’s missing electron is replaced by extracting a low-energy electron from water. Removing one electron from a water molecule, breaks one of the OH bonds and “splits” the water molecule into two H+ ions and an oxygen radical (oxygen with one electron). Splitting one H2O molecule releases two electrons (used to reduce PSII), two hydrogen atoms, and one atom of oxygen. However, splitting two molecules is required to form one molecule of diatomic O2 gas. In a typical leaf, about 10% of the oxygen is used by mitochondria in the leaf to support oxidative phosphorylation. The remainder escapes to the atmosphere where it is used by aerobic organisms to support respiration.

Generating Energy Carriers: ATP and NADPH

As electrons move through the proteins that reside between PSII and PSI, they lose energy. This energy is used to move hydrogen atoms from the stromal side of the membrane to the thylakoid lumen. Those hydrogen atoms, plus the ones produced by splitting water, accumulate in the thylakoid lumen and provide an electrochemical gradient that will be used to synthesize ATP in a later step. Because the electrons have lost energy prior to their arrival at PSI, they must be re-energized by another photon at PSI. That energy is relayed to the PSI reaction center, which is oxidized and sends a high-energy electron to NADP reductase, which reduces NADP+ to form NADPH. Thus, PSII captures the energy to create proton gradients to make ATP, and PSI captures the energy to reduce NADP+ into NADPH. The two photosystems work in concert, in part, to guarantee that the production of NADPH will roughly equal the production of ATP. Other mechanisms exist to fine-tune that ratio to exactly match the chloroplast’s constantly changing energy needs.

The buildup of hydrogen ions inside the thylakoid lumen creates a concentration gradient. The ions build up energy because of diffusion and because they all have the same electrical charge, repelling each other. The passive diffusion of hydrogen ions from high concentration (in the thylakoid lumen) to low concentration (in the stroma) is harnessed to create ATP, just as in the electron transport chain of cellular respiration.

To release this energy, hydrogen ions will rush through any opening, similar to water jetting through a hole in a dam. In the thylakoid, that opening is a passage through a specialized protein channel called the ATP synthase. The energy released by the hydrogen ion stream allows ATP synthase to attach a third phosphate group to ADP, which forms a molecule of ATP (Figure 7.3.4).

Practice Questions

Video 7.3.1. Photosynthesis: Part 5: Light Reactions | HHMI BioInteractive Video by biointeractive

Glossary

ATP synthase

membrane bound enzyme that uses the energy released by hydrogen ions flowing down their concentration gradient to catalyze the formation of ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate

NADP reductase

enzyme that is receives electrons from photosystem I and catalyzes the reduction of NADP+ to form NADPH

photosystem I

membrane bound protein complex that captures light and passes electrons to NADP reductase

photosystem II

membrane bound protein complex that captures light and oxidizes H2O to form O2 and passes the electrons released in the process to the electron transport chain in the thylakoid membrane.

Figure Descriptions

Figure 7.3.1. At the top, a bright photo of the sun is magnified into a horizontal rainbow bar labeled violet, blue, green, yellow, orange, red, representing visible light. Beneath it, a longer black band depicts the electromagnetic spectrum with a wavy red line whose crests spread farther apart from left to right, indicating increasing wavelength / decreasing energy. Labeled regions run left to right as gamma rays to X-rays to ultraviolet (UV) to visible light to infrared (IR) to microwaves to radio, showing that the slice of visible light occupies only a narrow band between UV and IR while the sun emits energy across many wavelengths. [Return to Figure 7.3.1]

Figure 7.3.2. The diagram titled “How a Photosystem Harvests Light” shows a Photosystem embedded in a thylakoid lipid bilayer, with the Stroma above and Thylakoid Space (Interior of Thylakoid) below. A yellow Photon strikes the outer Pigment Molecules that make up the Light-Harvesting Complexes; curved arrows labeled Transfer of Energy indicate excitation moving from pigment to pigment toward the central Reaction-Center Complex, where a Special Pair of Chlorophyll a Molecules sits at the base. From this pair, two red arrows point upward to the Primary Electron Acceptor, indicating that an electron excited by the transferred light energy is passed out of the reaction center and must be replaced for the photosystem to continue operating. [Return to Figure 7.3.2]

Figure 7.3.3. The figure compares common hydrophobic pigments in the thylakoid membrane. Panel (a) Chlorophyll a and (b) Chlorophyll b show nearly identical ring-and-tail structures; each has a red box highlighting the single difference between them. Panel (c) β-carotene is drawn as a long chain of alternating double bonds with no central ring like the chlorophylls; this pigment gives carrots their orange color. Panel (d) presents a graph of absorbance spectrum with wavelength along the x-axis and absorbance on the y-axis; three colored curves illustrate that each pigment absorbs light at different wavelengths (chlorophyll a and b strongly in the blue and red regions, and β-carotene primarily in the blue/blue-green) explaining green leaves and orange carrots. [Return to Figure 7.3.3]

Figure 7.3.4. The cutaway shows a Thylakoid Membrane separating Stroma (Low H⁺ Concentration) from Thylakoid Space (High H⁺ Concentration). At left, Light strikes Photosystem II, where H₂O is split to release O₂, H⁺, and electrons; the electrons move to Pq and through the Cytochrome Complex to Pc before reaching Photosystem I, which is hit by Light again. From PSI, electrons pass to Fd and then to NADP⁺ Reductase, reducing NADP⁺ + H⁺ → NADPH on the stromal side. Red dashed arrows indicate H⁺ being pumped into the lumen during electron flow, adding to the protons produced by water splitting, while formation of NADPH removes H⁺ from the stroma. together establishing the labeled high/low proton gradient. At center right, ATP Synthase uses this gradient as ADP + Pᵢ → ATP, and a curved arrow shows ATP (and NADPH) feeding the Calvin Cycle. [Return to Figure 7.3.4]

Licenses and Attributions

“7.3 Photosynthesis: Light-Dependent Reactions” is adapted from “8.2 The Light-Dependent Reactions of Photosynthesis” by Mary Ann Clark, Matthew Douglas, and Jung Choi for OpenStax Biology 2e under CC-BY 4.0. “7.3 Photosynthesis: Light-Dependent Reactions” is licensed under CC-BY-NC 4.0.

Media Attributions

- Wavelengths of Light

- Photosystem Harvests Light

- Light Absorbing pigments

- Light-dependent reactions diagram

membrane bound protein complex that captures light and oxidizes H2O to form O2 and passes the electrons released in the process to the electron transport chain in the thylakoid membrane.

membrane bound protein complex that captures light and passes electrons to NADP reductase

enzyme that is receives electrons from photosystem I and catalyzes the reduction of NADP+ to form NADPH

membrane bound enzyme that uses the energy released by hydrogen ions flowing down their concentration gradient to catalyze the formation of ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate