14.2 The Genetic Code

Elizabeth Dahlhoff

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Explain more specific details of the “central dogma” of information flow.

- Describe the genetic code and how the nucleotide sequence prescribes the amino acid and the protein sequence.

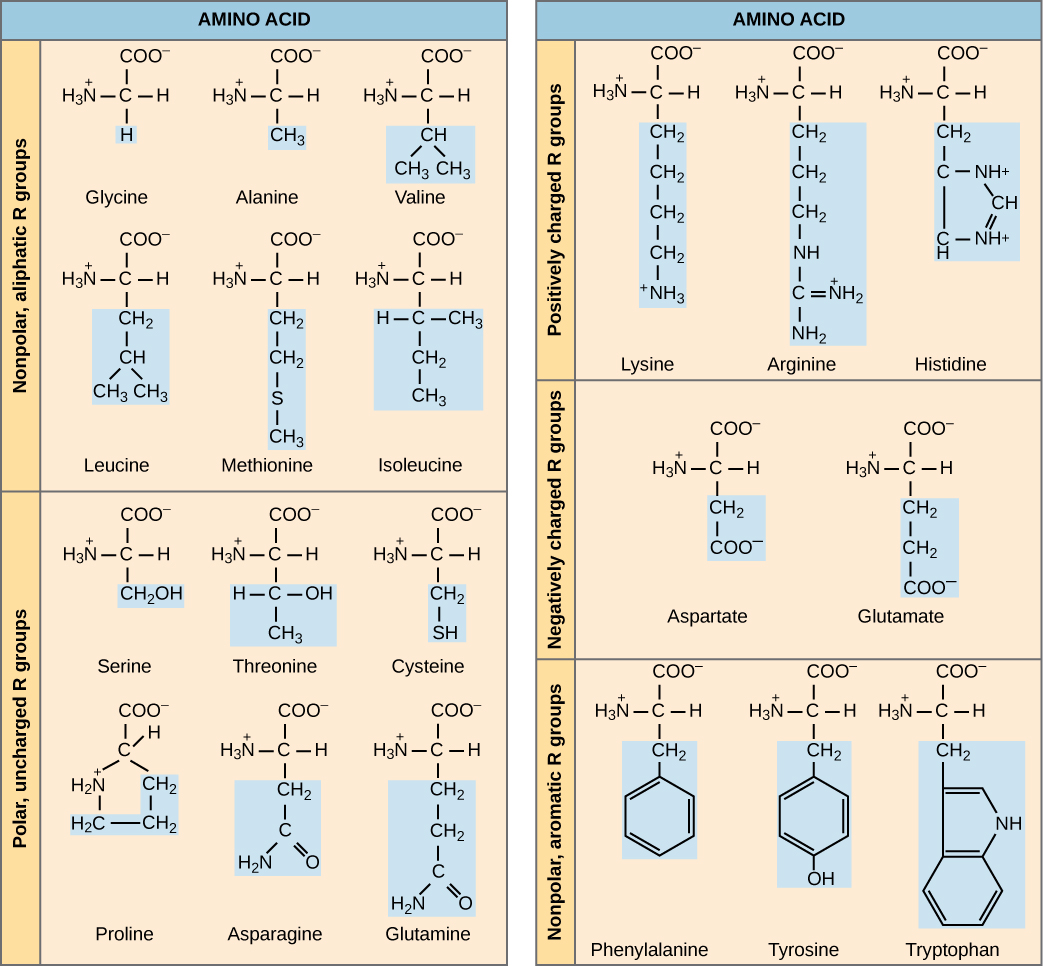

The Genetic Alphabet: Nucleotides, Codons, and Amino Acids

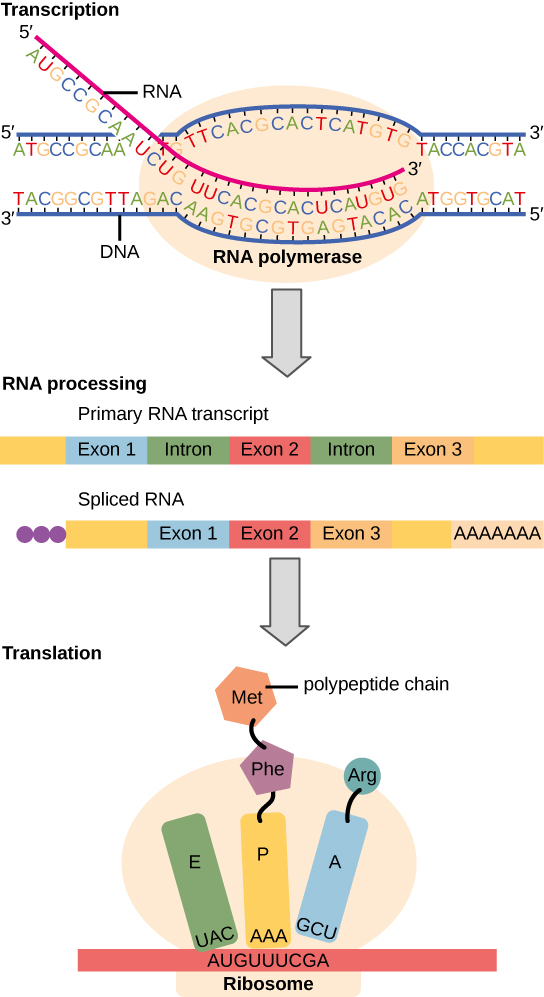

The cellular process of transcription generates messenger RNA (mRNA), a mobile molecular copy of one or more genes with an alphabet of A, C, G, and uracil (U), which substitutes for thymine (T) in RNA molecules. Translation of the mRNA template converts nucleotide-based genetic information into a protein product. Protein sequences consist of 20 commonly occurring amino acids; therefore, it can be said that the protein alphabet consists of 20 letters. Each amino acid is defined by a three-nucleotide sequence called the triplet codon. Different amino acids have different chemistries (such as acidic versus basic, or polar and nonpolar) and different structural constraints. Variation in amino acid sequence gives rise to enormous variation in protein structure and function.

The Central Dogma: DNA Encodes RNA; RNA Encodes Protein

The flow of genetic information in cells from DNA to mRNA to protein is described by the Central Dogma, which states that genes specify the sequence of mRNAs, which in turn specify the sequence of proteins. The decoding of one molecule to another is performed by specific proteins and RNAs. Instructions on DNA are transcribed onto messenger RNA. Ribosomes are able to read the genetic information inscribed on a strand of messenger RNA and use this information to string amino acids together into a protein. In prokaryotic organisms, mRNAs are translated directly into protein; in eukaryotes, mRNAs need to be translocated from the nucleus (where transcription occurs) into the cytosol, where protein synthesis occurs. Eukaryotic mRNA also needs to be processed and edited. This process is discussed in a later chapter.

The Genetic Code Is Degenerate and Universal

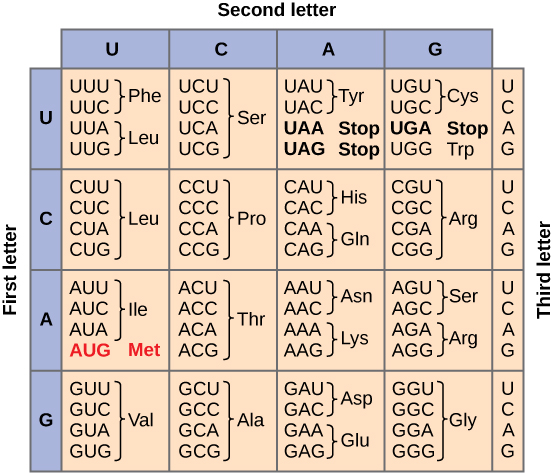

Given the different numbers of “letters” in the mRNA and protein “alphabets,” scientists theorized that combinations of nucleotides corresponded to single amino acids. Nucleotide doublets would not be sufficient to specify every amino acid because there are only 16 possible two-nucleotide combinations (42). In contrast, there are 64 possible nucleotide triplets (43), which is far more than the number of amino acids. Scientists theorized that amino acids were encoded by nucleotide triplets and that the genetic code was degenerate. In other words, a given amino acid could be encoded by more than one nucleotide triplet. This was later confirmed experimentally. This demonstrated that three nucleotides specify each amino acid. These nucleotide triplets are called codons. The insertion of one or two nucleotides completely changed the triplet reading frame, thereby altering the message for every subsequent amino acid. Though insertion of three nucleotides caused an extra amino acid to be inserted during translation, the integrity of the rest of the protein was maintained. Scientists painstakingly solved the genetic code by translating synthetic mRNAs in vitro and sequencing the proteins they specified. Figure 14.2.3 shows the genetic code for translating each nucleotide triplet in mRNA into an amino acid or a termination signal in a nascent protein.

In addition to instructing the addition of a specific amino acid to a polypeptide chain, three of the 64 codons terminate protein synthesis and release the polypeptide from the translation machinery. These triplets are called nonsense codons, or stop codons. Another codon, AUG, also has a special function. In addition to specifying the amino acid methionine, it also serves as the start codon to initiate translation. The reading frame for translation is set by the AUG start codon near the 5' end of the mRNA.

The genetic code is universal. With a few exceptions, virtually all species use the same genetic code for protein synthesis. Conservation of codons means that a purified mRNA encoding something like a globin protein in horses could be transferred to a tulip cell, and the tulip would synthesize horse globin. That there is only one genetic code is powerful evidence that all of life on Earth shares a common origin, especially considering that there are about 1084 possible combinations of 20 amino acids and 64 triplet codons.

Practice Translating a Gene

To get a feel for how this works, here is an exercise where you can transcribe a gene and translate it to protein using complementary pairing and the genetic code.

Degeneracy is believed to be a cellular mechanism to reduce the negative impact of random mutations. Codons that specify the same amino acid typically only differ by one nucleotide. In addition, amino acids with chemically similar side chains are encoded by similar codons. This nuance of the genetic code ensures that a single-nucleotide substitution mutation might either specify the same amino acid but have no effect or specify a similar amino acid, preventing the protein from being rendered completely nonfunctional. The role and impact of mutations is discussed in a later section.

Practice Questions

Section Summary

The genetic code refers to the DNA alphabet (A, T, C, G), the RNA alphabet (A, U, C, G), and the polypeptide alphabet (20 amino acids). The Central Dogma describes the flow of genetic information in the cell from genes to mRNA to proteins. Genes are used to make mRNA by the process of transcription; mRNA is used to synthesize proteins by the process of translation. The genetic code is degenerate because 64 triplet codons in mRNA specify only 20 amino acids and three nonsense codons. Almost every species on the planet uses the same genetic code.

Glossary

- codon

- three consecutive nucleotides in mRNA that specify the insertion of an amino acid or the release of a polypeptide chain during translation

- degeneracy

- (of the genetic code) describes that a given amino acid can be encoded by more than one nucleotide triplet; the code is degenerate, but not ambiguous

- nonsense (stop) codon

- one of the three mRNA codons that specifies termination of translation

- reading frame

- sequence of triplet codons in mRNA that specify a particular protein; a ribosome shift of one or two nucleotides in either direction completely abolishes synthesis of that protein

Figure Descriptions

Figure 14.2.1. This diagram shows the molecular structures of the 20 amino acids found in proteins, grouped by the chemical properties of their side chains (R groups). On the left, amino acids with nonpolar, aliphatic R groups (glycine, alanine, valine, leucine, methionine, and isoleucine) have hydrocarbon side chains that make them hydrophobic. Also on the left are polar, uncharged R groups, including serine, threonine, cysteine, proline, asparagine, and glutamine, which contain functional groups like hydroxyl, sulfhydryl, or amides that make them hydrophilic but uncharged. On the right, amino acids with positively charged R groups (lysine, arginine, and histidine) contain basic side chains that carry a positive charge at physiological pH, while negatively charged R groups, which are found in aspartate and glutamate, have acidic carboxyl side chains. At the bottom right, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan are categorized as having nonpolar, aromatic R groups due to their ring structures. Each amino acid is represented with a central carbon atom bonded to an amino group (H₃N⁺), a carboxyl group (COO⁻), a hydrogen atom, and a unique R group, which is highlighted in blue. [Return to Figure 14.2.1]

Figure 14.2.2. This diagram illustrates the process of gene expression from DNA to protein. At the top, transcription occurs as RNA polymerase reads the DNA strand to synthesize a complementary RNA strand. The DNA strand has base sequences with letters such as A, T, C, and G, while the RNA strand contains A, U, C, and G, demonstrating base pairing rules (A with U, T with A, C with G, and G with C). The primary RNA transcript includes both exons (colored blue, red, and orange) and introns (green), which are removed during RNA processing, resulting in a spliced RNA containing only the exons and a poly-A tail. In the final stage, translation occurs as the spliced RNA is read by a ribosome. Codons (AUG, UUU, CGA) are matched with tRNA anticodons (UAC, AAA, GCU), each carrying a specific amino acid. A polypeptide chain begins to form with methionine (Met), phenylalanine (Phe), and arginine (Arg) linked together. [Return to Figure 14.2.2]

Figure 14.2.3. This is a codon chart used to decode messenger RNA (mRNA) sequences into amino acids during translation. It is arranged as a table where the rows represent the first base of an RNA codon, the columns represent the second base, and the cells list the third base and the resulting amino acid. For example, the codon AUG is highlighted in red and codes for methionine (Met), which also serves as the start codon for protein synthesis. Other codons code for amino acids like leucine (Leu), proline (Pro), and glycine (Gly), depending on the combination of three RNA bases. Three codons (UAA, UAG, and UGA) are labeled as stop codons, signaling the end of translation. Each codon is made of a triplet of RNA bases (A, U, C, G), and each corresponds to a specific amino acid or signal. [Return to Figure 14.2.3]

Licenses and Attributions

This chapter, "The Genetic Code," by Elizabeth Dahlhoff, is adapted from "The Genetic Code" in Biology by Open Stax College (University of Hawaii) under a CC BY-NC 4.0 license. This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 license.