Chapter 2 Atoms, Molecules, and Ions

2.5 The Periodic Table

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- State the periodic law and explain the organization of elements in the periodic table

- Predict the general properties of elements based on their location within the periodic table

- Identify metals, nonmetals, and metalloids by their properties and/or location on the periodic table

As early chemists worked to purify ores and discovered more elements, they realized that various elements could be grouped together by their similar chemical behaviors. One such grouping includes lithium (Li), sodium (Na), and potassium (K): These elements are all shiny, conduct heat and electricity well, and have similar chemical properties. A second grouping includes calcium (Ca), strontium (Sr), and barium (Ba), which also are shiny, good conductors of heat and electricity, and have chemical properties in common. However, the specific properties of these two groupings are notably different from each other. For example: Li, Na, and K are much more reactive than are Ca, Sr, and Ba; Li, Na, and K form compounds with oxygen in a ratio of two of their atoms to one oxygen atom, whereas Ca, Sr, and Ba form compounds with one of their atoms to one oxygen atom. Fluorine (F), chlorine (Cl), bromine (Br), and iodine (I) also exhibit similar properties to each other, but these properties are drastically different from those of any of the elements above.

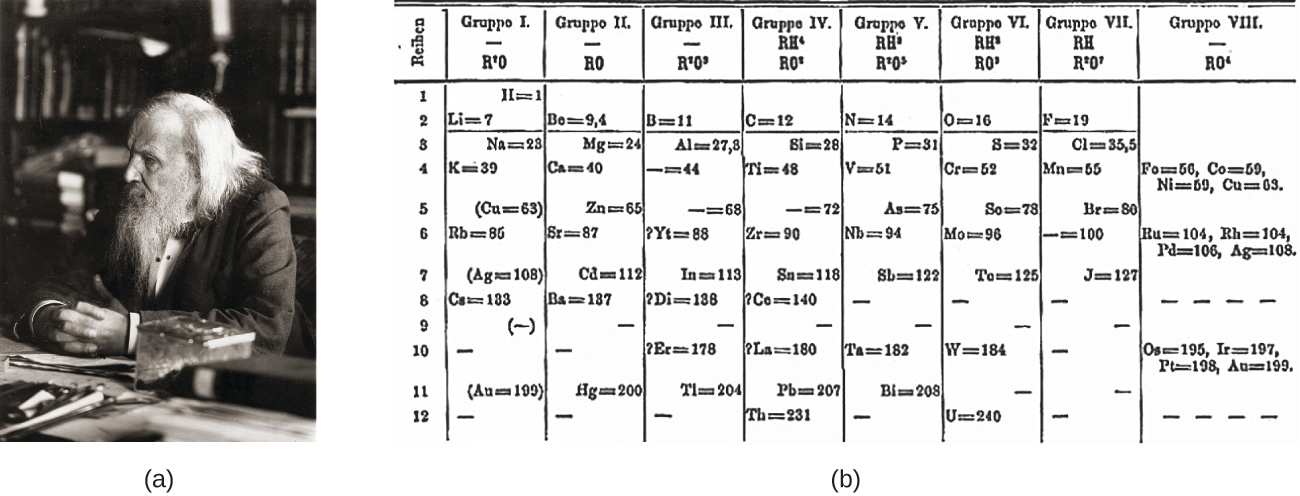

Dimitri Mendeleev in Russia (1869) and Lothar Meyer in Germany (1870) independently recognized that there was a periodic relationship among the properties of the elements known at that time. Both published tables with the elements arranged according to increasing atomic mass. But Mendeleev went one step further than Meyer: He used his table to predict the existence of elements that would have the properties similar to aluminum and silicon but were yet unknown. The discoveries of gallium (1875) and germanium (1886) provided great support for Mendeleev’s work. Although Mendeleev and Meyer had a long dispute over priority, Mendeleev’s contributions to the development of the periodic table are now more widely recognized (Figure 2.25).

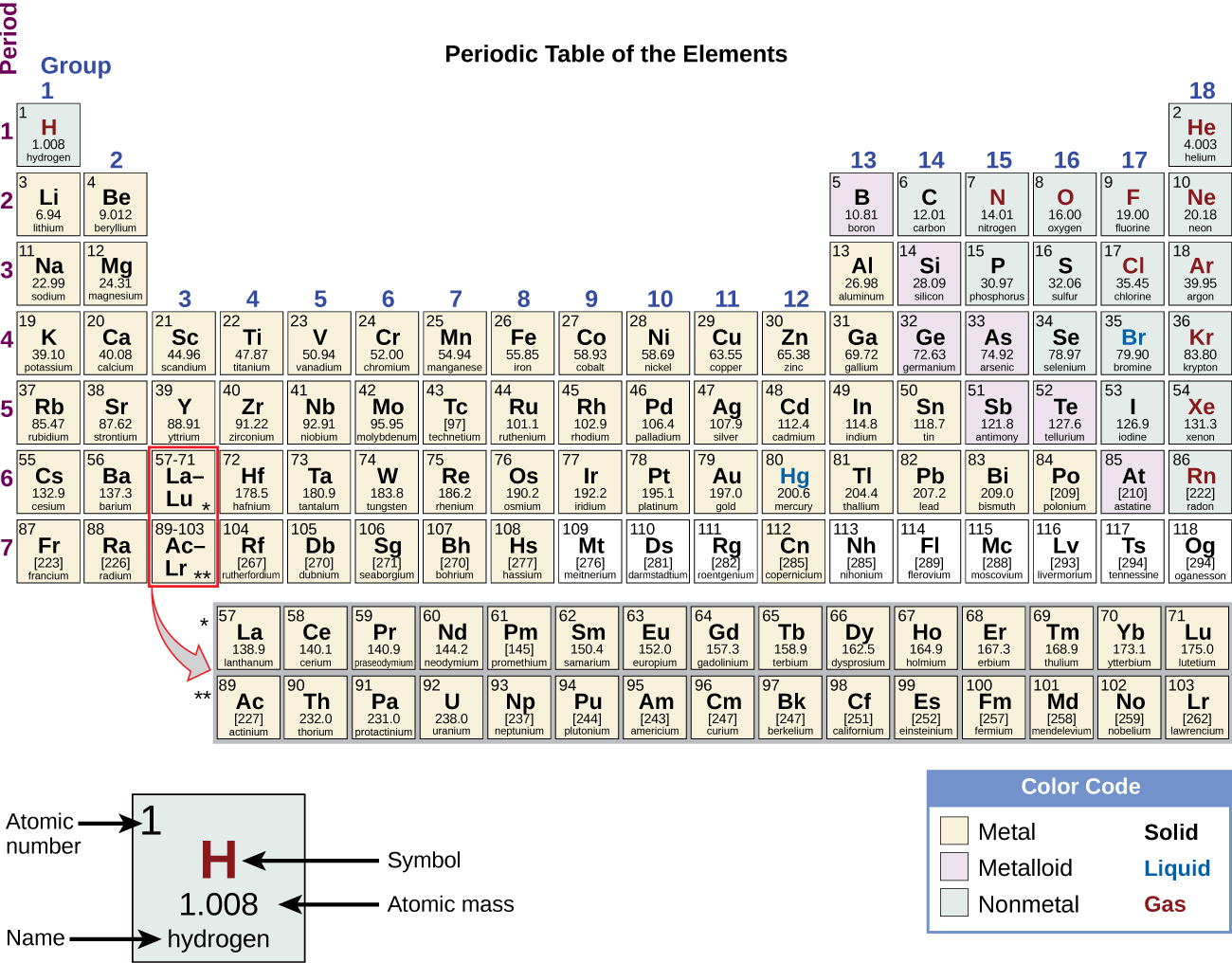

By the twentieth century, it became apparent that the periodic relationship involved atomic numbers rather than atomic masses. The modern statement of this relationship, the periodic law, is as follows: The properties of the elements are periodic functions of their atomic numbers. A modern periodic table arranges the elements in increasing order of their atomic numbers and groups atoms with similar properties in the same vertical column (Figure 2.26). Each box represents an element and contains its atomic number, symbol, average atomic mass, and (sometimes) name. The elements are arranged in seven horizontal rows, called periods or series, and 18 vertical columns, called groups. Groups are labeled at the top of each column. In the United States, the labels traditionally were numerals with capital letters. However, International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) recommends that the numbers 1 through 18 be used, and these labels are more common. For the table to fit on a single page, parts of two of the rows, a total of 14 columns, are usually written below the main body of the table.

Even after the periodic nature of elements and the table itself were widely accepted, gaps remained. Mendeleev had predicted, and others including Henry Moseley had later confirmed, that there should be elements below Manganese in Group 7. German chemists Ida Tacke and Walter Noddack set out to find the elements, a quest being pursued by scientists around the world. Their method was unique in that they did not only consider the properties of manganese, but also the elements horizontally adjacent to the missing elements 43 and 75 on the table. Thus, by investigating ores containing minerals of ruthenium (Ru), tungsten (W), osmium (Os), and so on, they were able to identify naturally occurring elements that helped complete the table. Rhenium, one of their discoveries, was one of the last natural elements to be discovered and is the last stable element to be discovered. (Francium, the last natural element to be discovered, was identified by Marguerite Perey in 1939.)

Many elements differ dramatically in their chemical and physical properties, but some elements are similar in their behaviors. For example, many elements appear shiny, are malleable (able to be deformed without breaking) and ductile (can be drawn into wires), and conduct heat and electricity well. Other elements are not shiny, malleable, or ductile, and are poor conductors of heat and electricity. We can sort the elements into large classes with common properties: metals (elements that are shiny, malleable, good conductors of heat and electricity—shaded yellow); nonmetals (elements that appear dull, poor conductors of heat and electricity—shaded green); and metalloids (elements that conduct heat and electricity moderately well, and possess some properties of metals and some properties of nonmetals—shaded purple).

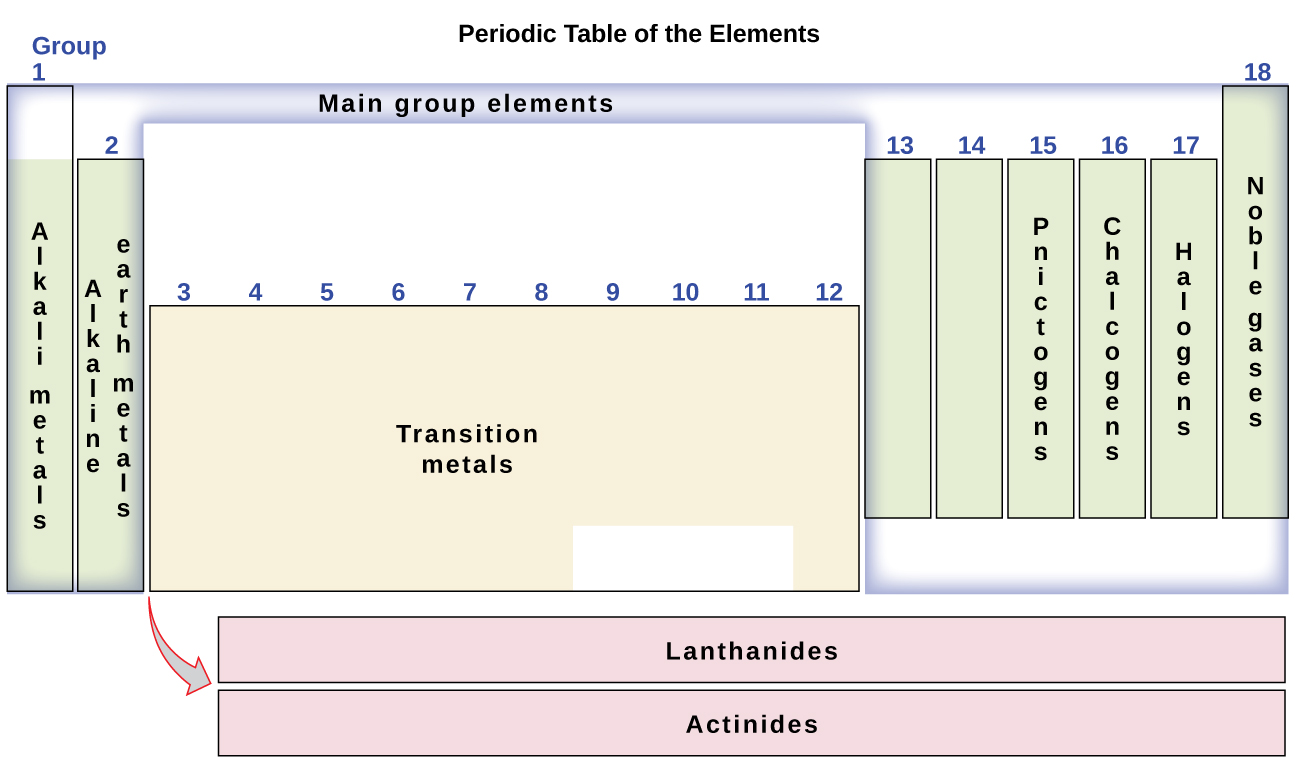

The elements can also be classified into the main-group elements (or representative elements) in the columns labeled 1, 2, and 13–18; the transition metals in the columns labeled 3–12; and inner transition metals in the two rows at the bottom of the table (the top-row elements are called lanthanides and the bottom-row elements are actinides; Figure 2.27). The lanthanides (starting with Lanthanium) plus Scandium (Z=21) and Yttrium (Z=39) are collectively called rare earth elements. “Rare” earth elements are not uncommon; they are just spread around the world such that large deposits are hard to find. You can thank these elements for making products energy efficient, lighter, and smaller; in fact, they play key roles in electric vehicles, aircraft engines, medical equipment, radar systems, flat screen TVs, and wind turbines.

The elements can be subdivided further by more specific properties, such as the composition of the compounds they form. For example, the elements in group 1 (the first column) form compounds that consist of one atom of the element and one atom of hydrogen. These elements (except hydrogen) are known as alkali metals, and they all have similar chemical properties. The elements in group 2 (the second column) form compounds consisting of one atom of the element and two atoms of hydrogen: These are called alkaline earth metals, with similar properties among members of that group. Other groups with specific names are the pnictogens (group 15), chalcogens (group 16), halogens (group 17), and the noble gases (group 18, also known as inert gases). The groups can also be referred to by the first element of the group: For example, the chalcogens can be called the oxygen group or oxygen family. Hydrogen is a unique, nonmetallic element with properties similar to both group 1 and group 17 elements. For that reason, hydrogen may either be shown at the top of both groups or by itself.

Per the IUPAC definition, group 12 elements are not transition metals, though they are often referred to as such. Additional details on this group’s elements are provided in a chapter on transition metals and coordination chemistry.

Figure 2.27.The periodic table organizes elements with similar properties into groups.

Link to Learning

Click on this link for an interactive periodic table, which you can use to explore the properties of the elements (includes podcasts and videos of each element). You may also want to try this one that shows photos of all the elements.

Example 2.7 − Naming Groups of Elements

Atoms of each of the following elements are essential for life. Give the group name for each element.

chlorine (Cl)

halogen

calcium (Ca)

alkaline earth metal

sodium (Na)

alkali metal

sulfur (S)

chalcogen

Check Your Learning

As you will learn in your further study of chemistry, elements in groups often behave in a somewhat similar manner. This is partly due to the number of electrons in their outer shell and their similar readiness to bond. These shared properties can have far-ranging implications in nature, science, and medicine. For example, when Gertrude Elion and George Hitchens were investigating ways to interrupt cell and virus replication to fight diseases, they utilized the similarity between sulfur and oxygen (both in Group 16) and their capacity to bond in similar ways. Elion focused on purines, which are key components of DNA and which contain oxygen. She found that by introducing sulfur-based compounds (called purine analogues) that mimic the structure of purines, molecules within DNA would bond to the analogues rather than the “regular” DNA purine. With the normal DNA bonding and structure altered, Elion successfully interrupted cell replication. At its core, the strategy worked because of the similarity between sulfur and oxygen. Her discovery led directly to important treatments for leukemia. Overall, Elion’s work with George Hitchens not only led to more treatments, but also changed the entire methodology of drug development. By using specific elements and compounds to target specific aspects of tumor cells, viruses, and bacteria, they laid the groundwork for many of today’s most common and important medicines, used to help millions of people each year. They were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1988.

In studying the periodic table, you might have noticed something about the atomic masses of some of the elements. Element 43 (technetium), element 61 (promethium), and most of the elements with atomic number 84 (polonium) and higher have their atomic mass given in square brackets. This is done for elements that consist entirely of unstable, radioactive isotopes (you will learn more about radioactivity in the nuclear chemistry chapter). An average atomic weight cannot be determined for these elements because their radioisotopes may vary significantly in relative abundance, depending on the source, or may not even exist in nature. The number in square brackets is the atomic mass number (an approximate atomic mass) of the most stable isotope of that element.

Portrait of a Chemist

Darleane C. Hoffman

Dr. Darleane Christian Hoffman is a pioneering American nuclear chemist renowned for her groundbreaking work in the discovery and characterization of heavy elements. Born in Terril, Iowa, in 1926, she initially pursued applied art at Iowa State College but switched to chemistry after being inspired by a female professor. She earned her BS in 1948 and PhD in 1951 in nuclear chemistry from Iowa State University.

Dr. Hoffman made significant contributions to the field of nuclear chemistry, including the discovery of seaborgium (element 106), the development of methods to study unstable transuranium elements, and the discovery of plutonium-244. Dr. Hoffman’s work has been instrumental in expanding the periodic table and deepening our understanding of the heaviest elements. Her research has implications for nuclear chemistry, environmental science, and our comprehension of atomic structure. In 1983, Dr. Hoffman became the first woman to receive the American Chemical Society’s Award for Nuclear Chemistry. She was also awarded the National Medal of Science in 1997 and the Priestley Medal in 2000, recognizing her outstanding contributions to the field.

Media Attributions

- Darleane C. Hoffman 2012 © Science History Institute is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license