Chapter 13 Fundamental Equilibrium Concepts

13.2 Equilibrium Constants

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Derive reaction quotients from chemical equations representing homogeneous and heterogeneous reactions

- Calculate values of reaction quotients and equilibrium constants, using concentrations and pressures

- Relate the magnitude of an equilibrium constant to properties of the chemical system

The status of a reversible reaction is conveniently assessed by evaluating its reaction quotient (Q). For a reversible reaction described by:

the reaction quotient is derived directly from the stoichiometry of the balanced equation as:

Note that the reaction quotient equations above are a simplification of more rigorous expressions that use relative values for concentrations and pressures rather than absolute values. These relative concentration and pressure values are dimensionless (they have no units); consequently, so are the reaction quotients. For purposes of this introductory text, it will suffice to use the simplified equations and to disregard units when computing Q. In most cases, this will introduce only modest errors in calculations involving reaction quotients.

Example 13.1 – Writing Reaction Quotient Expressions

Write the concentration-based reaction quotient expression for each of the following reactions:

(a) 3 O2(g) ⇌ 2 O3(g)

(b) N2(g) + 3 H2(g) ⇌ 2 NH3(g)

(c) 4 NH3(g) + 7 O2(g) ⇌ 4 NO2(g) + 6 H2O(g)

Solution

(a)

(b)

(c)

Check Your Learning

The numerical value of Q varies as a reaction proceeds towards equilibrium; therefore, it can serve as a useful indicator of the reaction’s status. To illustrate this point, consider the oxidation of sulfur dioxide:

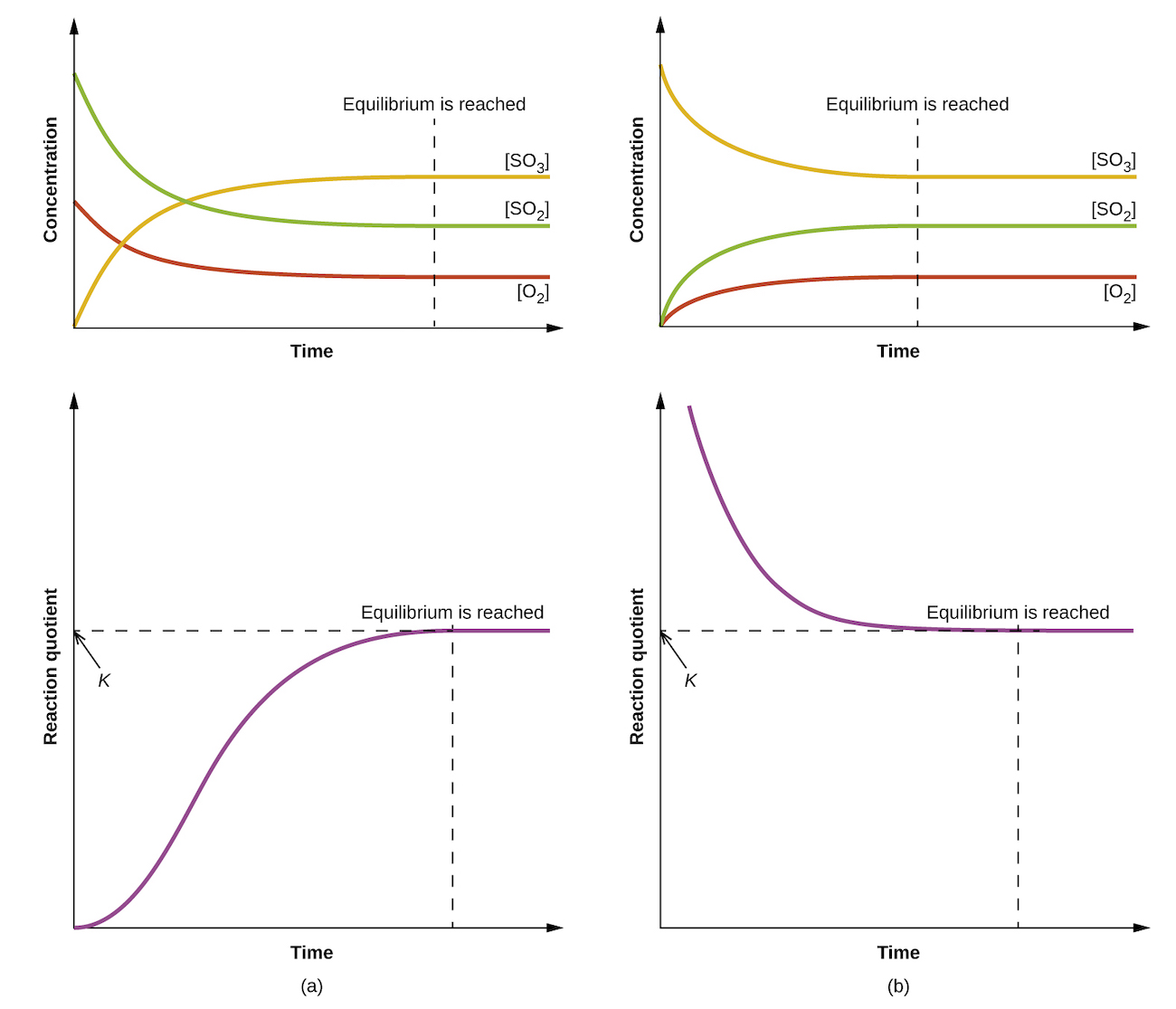

Two different experimental scenarios are depicted in Figure 13.5, one in which this reaction is initiated with a mixture of reactants only, SO2 and O2, and another that begins with only product, SO3. For the reaction that begins with a mixture of reactants only, Q is initially equal to zero:

As the reaction proceeds toward equilibrium in the forward direction, reactant concentrations decrease (as does the denominator of Qc), product concentration increases (as does the numerator of Qc), and the reaction quotient consequently increases. When equilibrium is achieved, the concentrations of reactants and product remain constant, as does the value of Qc.

If the reaction begins with only product present, the value of Qc is initially undefined (immeasurably large, or infinite):

In this case, the reaction proceeds toward equilibrium in the reverse direction. The product concentration and the numerator of Qc decrease with time, the reactant concentrations and the denominator of Qc increase, and the reaction quotient consequently decreases until it becomes constant at equilibrium.

The constant value of Q exhibited by a system at equilibrium is called the equilibrium constant, K:

Comparison of the data plots in Figure 13.5 shows that both experimental scenarios resulted in the same value for the equilibrium constant. This is a general observation for all equilibrium systems, known as the law of mass action: At a given temperature, the reaction quotient for a system at equilibrium is constant.

Gaseous nitrogen dioxide forms dinitrogen tetroxide according to this equation:

When 0.10 mol NO2 is added to a 1.0-L flask at 25°C, the concentration changes so that at equilibrium, [NO2] = 0.016 M and [N2O4] = 0.042 M.

(a) What is the value of the reaction quotient before any reaction occurs?

(b) What is the value of the equilibrium constant for the reaction?

Solution

As for all equilibrium calculations in this text, use the simplified equations for Q and K and disregard any concentration or pressure units, as noted previously in this section.

(a) Before any product is formed:

(b) At equilibrium:

The equilibrium constant is 1.6 × 102.

Check Your Learning

Click here to see this problem worked through!

The equilibrium constant expression for this reaction is:

Plugging in the provided concentrations and ignoring units gives us:

By its definition, the magnitude of an equilibrium constant explicitly reflects the composition of a reaction mixture at equilibrium, and it may be interpreted with regard to the extent of the forward reaction:

- A reaction with a large K reaches equilibrium when most of the reactant has been converted to product.

- A reaction with a small K reached equilibrium after very little reactant has been converted to products.

It’s important to keep in mind that the magnitude of K does not indicate how rapidly or slowly equilibrium will be reached. Some equilibria are established so quickly as to be nearly instantaneous, and others so slowly that no perceptible change is observed over the course of days, years, or longer.

The equilibrium constant for a reaction can be used to predict the behavior of mixtures containing its reactants and/or products. As demonstrated by the sulfur dioxide oxidation process described above, a chemical reaction will proceed in whatever direction is necessary to achieve equilibrium. Comparing Q to K for an equilibrium system of interest allows prediction of what reaction (forward or reverse), if any, will occur:

- If Q is initially smaller than K (Q < K), the reaction will proceed towards the products (the forward direction)

- If Q is initially larger than K (Q > K), the reaction will proceed towards the reactants (the reverse direction)

Consider the reversible reaction shown below:

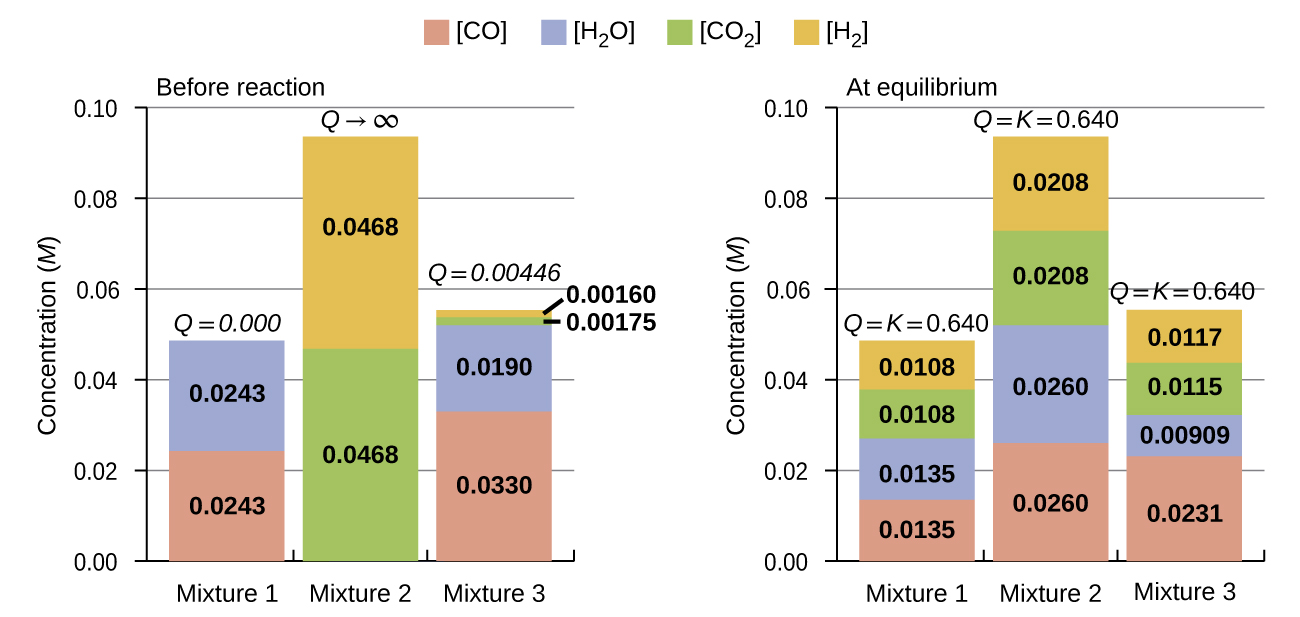

The bar charts in Figure 13.6 represent changes in reactant and product concentrations for three different reaction mixtures. The reaction quotients for mixtures 1 and 3 are initially lesser than the reaction’s equilibrium constant, so each of these mixtures will experience a net forward reaction to achieve equilibrium. The reaction quotient for mixture 2 is initially greater than the equilibrium constant, so this mixture will proceed in the reverse direction until equilibrium is established.

Example 13.3 – Predicting the Direction of Reaction

Given here are the starting concentrations of reactants and products for three experiments involving this reaction:

Determine in which direction the reaction proceeds as it goes to equilibrium in each of the three experiments shown.

|

Reactants or Products |

Experiment 1 |

Experiment 2 |

Experiment 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

[CO]i |

0.020 M |

0.011 M |

0.0094 M |

|

[H2O]i |

0.020 M |

0.0011 M |

0.0025 M |

|

[CO2]i |

0.0040 M |

0.037 M |

0.0015 M |

|

[H2]i |

0.0040 M |

0.046 M |

0.0076 M |

Solution

Experiment 1

Qc < Kc (0.040 < 0.64)

The reaction will proceed in the forward direction.

Experiment 2

Qc > Kc (140 > 0.64)

The reaction will proceed in the reverse direction.

Experiment 3

Qc < Kc (0.48 < 0.64)

The reaction will proceed in the forward direction.

Check Your Learning

Click here to see a walkthrough for question 1!

The form of Qc for this reaction is

Because the container is 1 L, we can directly write the molarity from the number of mols:

Click here for a walkthrough of question 3!

First, the mols of each species must be calculated:

Next, the concentrations should be calculated using the volume of the container:

Then, we can calculate Qc:

Note: if you do not keep trailing decimals while performing these calculations, you will instead calculate a value of around 0.28.

Homogeneous Equilibria

A homogeneous equilibrium is one in which all reactants and products (and any catalysts, if applicable) are present in the same phase. By this definition, homogeneous equilibria take place in solutions. These solutions are most commonly either liquid or gaseous phases, as shown by the examples below:

C2H2(aq) + 2 Br2(aq) ⇌ C2H2Br4(aq) [latex]K_c = \frac {[C_2H_2Br_4]}{[C_2H_2] \, [Br_2]^2}[/latex]

I2(aq) + I−(aq) ⇌ I3−(aq) [latex]K_c = \frac {[I_3^-]}{[I_2] \, [I^-]}[/latex]

HF(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + F−(aq) [latex]K_c = \frac {[H_3O^+] \, [F^-]}{[HF]}[/latex]

NH3(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ NH4+(aq) + OH−(aq) [latex]K_c = \frac {[NH_4^+] \, [OH^-]}{[NH_3]}[/latex]

These examples all involve aqueous solutions, those in which water functions as the solvent. In the last two examples, water also functions as a reactant, but its concentration is not included in the reaction quotient.

Relative concentrations for liquids and solids are equal to 1 and needn’t be included in Qc and Kc expressions. Consequently, reaction quotients and equilibrium constants include concentration or pressure terms only for gaseous and solute species.

The equilibria below all involve gas-phase solutions:

C2H6(g) ⇌ C2H4(g) + H2(g) [latex]K_c = \frac {[C_2H_4] \, [H_2]}{[C_2H_6]}[/latex]

3 O2(g) ⇌ 2 O3(g) [latex]K_c = \frac {[O_3]^2}{[I_2]^3}[/latex]

N2(g) + 3 H2(g) ⇌ 2 NH3(g) [latex]K_c = \frac {[NH_3]^2}{[N_2] \, [H_2]^3}[/latex]

C3H8(g) + 5 O2(g) ⇌ 3 CO2(g) + 4 H2O(g) [latex]K_c = \frac {[CO_2]^3 \, [H_2O]^4}{[C_3H_8] \, [O_2]^5}[/latex]

For gas-phase solutions, the equilibrium constant may be expressed in terms of either the molar concentrations (Kc) or partial pressures (Kp) of the reactants and products. A relation between these two K values may be simply derived from the ideal gas equation and the definition of molarity:

For the gas-phase reaction:

Example 13.4 – Calculation of KP

Write the equations relating Kc to KP for each of the following reactions:

(a) C2H6(g) ⇌ C2H4(g) + H2(g)

(b) CO(g) + H2O(g) ⇌ CO2(g) + H2(g)

(c) N2(g) + 3 H2(g) ⇌ 2 NH3(g)

Kc is equal to 0.28 for the following reaction at 900°C:

(d) What is KP at this temperature?

Solution

(a) Δn = (2) − (1) = 1

(b) Δn = (2) − (2) = 0

(c) Δn = (2) − (1 + 3) = −2

(d)

Check Your Learning

Click here to see a walkthrough for problem 4!

For this problem:

Plugging in the appropriate values and converting from degrees Celsius to Kelvin yields:

Heterogeneous Equilibria

A heterogeneous equilibrium involves reactants and products in two or more different phases, as illustrated by the following examples:

PbCl2(s) ⇌ Pb2+(aq) + 2 Cl−(aq) [latex]K_c = [Pb^{2+}] \, [Cl^-]^2[/latex]

CaO(s) + CO2(g) ⇌ CaCO3(s) [latex]K_c = \frac {1}{[CO_2]}[/latex]

C(s) + 2 S(g) ⇌ CS2(g) [latex]K_c = \frac {[CS_2]}{[S]^2}[/latex]

Br2(l) ⇌ Br2(g) [latex]K_c = [Br_2(g)][/latex]

Note that concentration terms are only included for gaseous and solute species. As discussed previously, relative concentrations for solids are equal to 1 and needn’t be included in Qc and Kc expressions.

Two of the above examples include terms for gaseous species only in their equilibrium constants, and so Kp expressions may also be written:

CaO(s) + CO2(g) ⇌ CaCO3(s) [latex]K_P = \frac {1}{P_{CO_2}}[/latex]

C(s) + 2 S(g) ⇌ CS2(g) [latex]K_P = \frac {P_{CS_2}}{P_S^2}[/latex]

Coupled Equilibria

The equilibrium systems discussed so far have all been relatively simple, involving just single reversible reactions. Many systems, however, involve two or more coupled equilibrium reactions, those which have in common one or more reactant or product species. Since the law of mass action allows for a straightforward derivation of equilibrium constant expressions from balanced chemical equations, the K value for a system involving coupled equilibria can be related to the K values of the individual reactions. Three basic manipulations are involved in this approach, as described below.

1. Changing the direction of a chemical equation essentially swaps the identities of “reactants” and “products,” and so the equilibrium constant for the reversed equation is simply the reciprocal of that for the forward equation:

A ⇌ B [latex]K_c = \frac {[B]}{[A]}[/latex]

B ⇌ A [latex]K_c' = \frac {[A]}{[B]}[/latex]

[latex]K_c' = \frac {1}{K_c}[/latex]

2. Changing the stoichiometric coefficients in an equation by some factor x results in an exponential change in the equilibrium constant by that same factor:

A ⇌ B [latex]K_c = \frac {[B]}{[A]}[/latex]

x A ⇌ x B [latex]K_c' = \frac {[B]^x}{[A]^x}[/latex]

[latex]K_c' = K_c^x[/latex]

3. Adding two or more equilibrium equations together yields an overall equation whose equilibrium constant is the mathematical product of the individual reaction’s K values:

A ⇌ B [latex]K_{c1} = \frac {[B]}{[A]}[/latex]

B ⇌ C [latex]K_{c2} = \frac {[C]}{[B]}[/latex]

The net reaction for these coupled equilibria is obtained by summing the two equilibrium equations and canceling any redundancies:

A + B ⇌ B + C

A + B ⇌ B + C

A ⇌ C [latex]K_c' = \frac {[C]}{[A]}[/latex]

Comparing the equilibrium constant for the net reaction to those for the two coupled equilibrium reactions reveals the following relationship:

[latex]K_{c1} \, K_{c2} = \frac {[B]}{[A]} \cdot \frac {[C]}{[B]} = \frac {\cancel {[B]} [C]}{[A] \cancel {[B]}} = \frac {[C]}{[A]} = K_c'[/latex]

[latex]K_c' = K_{c1} \, K_{c2}[/latex]

Example 13.5 demonstrates the use of this strategy in describing coupled equilibrium processes.

A mixture containing nitrogen, hydrogen, and iodine established the following equilibrium at 400°C:

Use the information below to calculate Kc for this reaction.

N2(g) + 3 H2(g) ⇌ 2 NH3(g) Kc1 = 0.50 at 400oC

Solution

The equilibrium equation of interest and its K value may be derived from the equations for the two coupled reactions as follows.

Reverse the first coupled reaction equation:

Multiply the second coupled reaction by 3:

Finally, add the two revised equations:

2 NH3(g) + 3 H2(g) + 3 I2(g) ⇌ N2(g) + 3 H2(g) + 6 HI(g)

2 NH3(g) + 3 I2(g) ⇌ N2(g) + 6 HI(g)

[latex]K_c = K_{c1}' \, K_{c2}' = (2.0)(1.2 \times 10^5) = 2.5 \times 10^5[/latex]

Check Your Learning

Click here for a walkthrough of these questions!

First, reverse reaction 1 and calculate the new equilibrium constant by taking the reciprocal of Kc1:

Co(s) + CO2(g) ⇌ CoO(s) + CO(g) K‘c1 = 1/490 = 0.0020

Then, add the above reaction to reaction 2. Calculate the new equilibrium constant by multiplying K‘c1 and Kc2:

Co(s) + CO2(g) ⇌ CoO(s) + CO(g)

+ CoO(s) + H2(g) ⇌ Co(s) + H2O(g)

H2(g) + CO2(g) ⇌ CO(g) + H2O(g) [latex]K_c = K_{c1}' \, K_{c2} = (0.0020)(67) = 0.14[/latex]