Chapter 14 Acid Base Equilibria

14.3 Relative Strengths of Acids and Bases

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Assess the relative strengths of acids and bases according to their ionization constants

- Carry out equilibrium calculations for weak acid–base systems

The relative strength of an acid or base is the extent to which it ionizes when dissolved in water:

- If the ionization reaction is essentially complete, the acid or base is termed strong

- If relatively little ionization occurs, the acid or base is weak

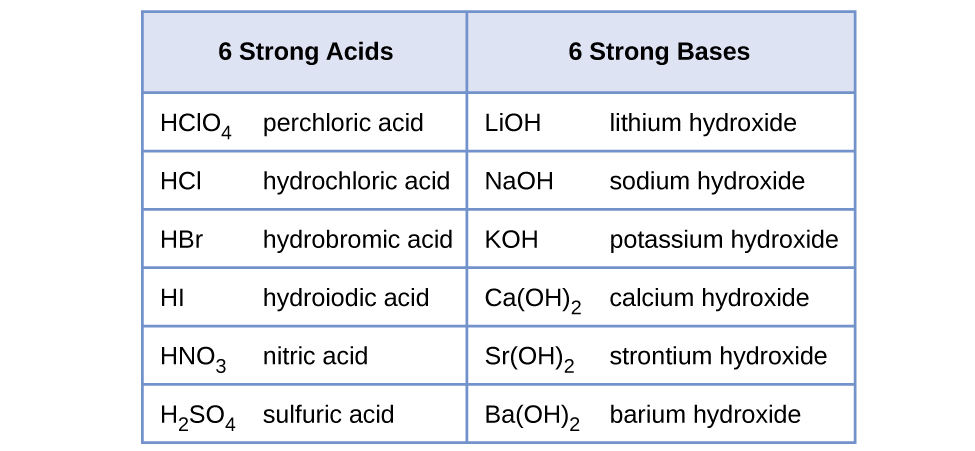

As will be evident throughout the remainder of this chapter, there are many more weak acids and bases than strong ones. The most common strong acids and bases are listed in Figure 14.6.

.

Strong and Weak Acids

The relative strengths of acids may be quantified by measuring their equilibrium constants in aqueous solutions. In solutions of the same concentration, stronger acids ionize to a greater extent, and so yield higher concentrations of hydronium ions than do weaker acids. The equilibrium constant for an acid is called the acid-ionization constant, Ka. For the reaction of an acid HA:

- The larger the Ka of an acid, the larger the concentration of H3O+ and A− relative to the concentration of the nonionized acid, HA, in an equilibrium mixture, and the stronger the acid.

- An acid is classified as “strong” when it undergoes complete ionization, in which case the concentration of HA is zero and the acid ionization constant is immeasurably large (Ka ≈ ∞).

- Acids that are partially ionized are called “weak,” and their acid ionization constants may be experimentally measured. A table of ionization constants for weak acids is provided in Appendix H.

To illustrate the first point, three acid ionization equations and Ka values are shown below. The ionization constants increase from first to last of the listed equations, indicating the relative acid strength increases in the order CH3CO2H < HNO2 < HSO4−:

CH3CO2H(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + CH3CO2−(aq) Ka = 1.8 × 10−5

Another measure of the strength of an acid is its percent ionization. The percent ionization of a weak acid is defined in terms of the composition of an equilibrium mixture:

Example 14.7 - Calculation of Percent Ionization from pH

Calculate the percent ionization of a 0.125-M solution of nitrous acid (a weak acid), with a pH of 2.09.

Solution

The percent ionization for an acid is:

(Recall the provided pH value of 2.09 is logarithmic, and so it contains just two significant digits, limiting the certainty of the computed percent ionization.)

Check Your Learning

Click here to see this problem worked through!

The percent ionization for acetic acid is:

Link to Learning

View the simulation of strong and weak acids and bases at the molecular level.

Strong and Weak Bases

Just as for acids, the relative strength of a base is reflected in the magnitude of its base-ionization constant (Kb) in aqueous solutions. In solutions of the same concentration, stronger bases ionize to a greater extent, and so yield higher hydroxide ion concentrations than do weaker bases. A stronger base has a larger ionization constant than does a weaker base. For the reaction of a base, B:

- The larger the Kb of a base, the larger the concentration of OH- and conjugate acid HB+ relative to the concentration of the base, B, in an equilibrium mixture, and the stronger the base.

- A base is classified as “strong” when it undergoes complete ionization, in which case the concentration of B is zero and the base ionization constant is immeasurably large (Kb ≈ ∞).

- Bases that are partially ionized are called “weak,” and their base ionization constants may be experimentally measured. A table of ionization constants for weak acids is provided in Appendix I.

Inspection of the data for three weak bases presented below shows the base strength increases in the order NO2− < CH2CO2− < NH3.

[latex][/latex]

NO2−(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ HNO2(aq) + OH−(aq) Kb = 2.17 × 10−11

As for acids, the relative strength of a base is also reflected in its percent ionization, computed as:

Relative Strengths of Conjugate Acid-Base Pairs

Logic suggests a relation between the relative strengths of conjugate acid-base pairs: if an acid is strong, it must be unfavorable for its conjugate base to accept protons and the base is weak (and vice versa). We can show this mathematically.

As discussed above, the strength of an acid or base is quantified by its ionization constant, Ka or Kb, which represents the extent of the acid or base ionization reaction. For the conjugate acid-base pair HA / A−, ionization equilibrium equations and ionization constant expressions are:

Adding these two chemical equations yields the equation for the autoionization for water:

As discussed in chapter 13, the equilibrium constant for a summed reaction is equal to the mathematical product of the equilibrium constants for the added reactions, and so:

This equation states the relation between ionization constants for any conjugate acid-base pair: namely, their mathematical product is equal to the ion product of water, Kw. By rearranging this equation, a reciprocal relation between the strengths of a conjugate acid-base pair becomes evident:

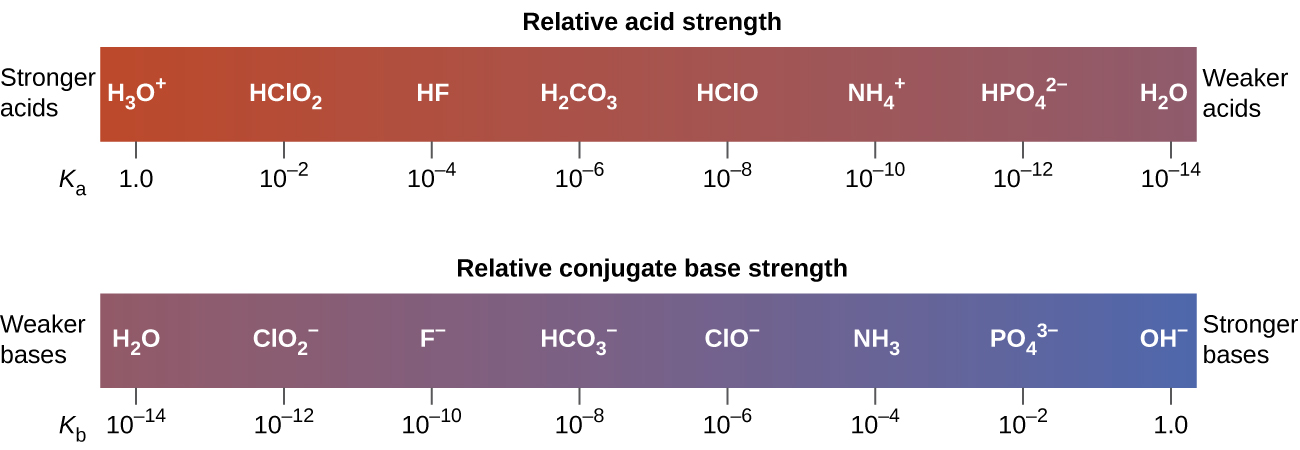

The inverse proportional relation between Ka and Kb means the stronger the acid or base, the weaker its conjugate partner. Figure 14.7 illustrates this relation for several conjugate acid-base pairs.

.

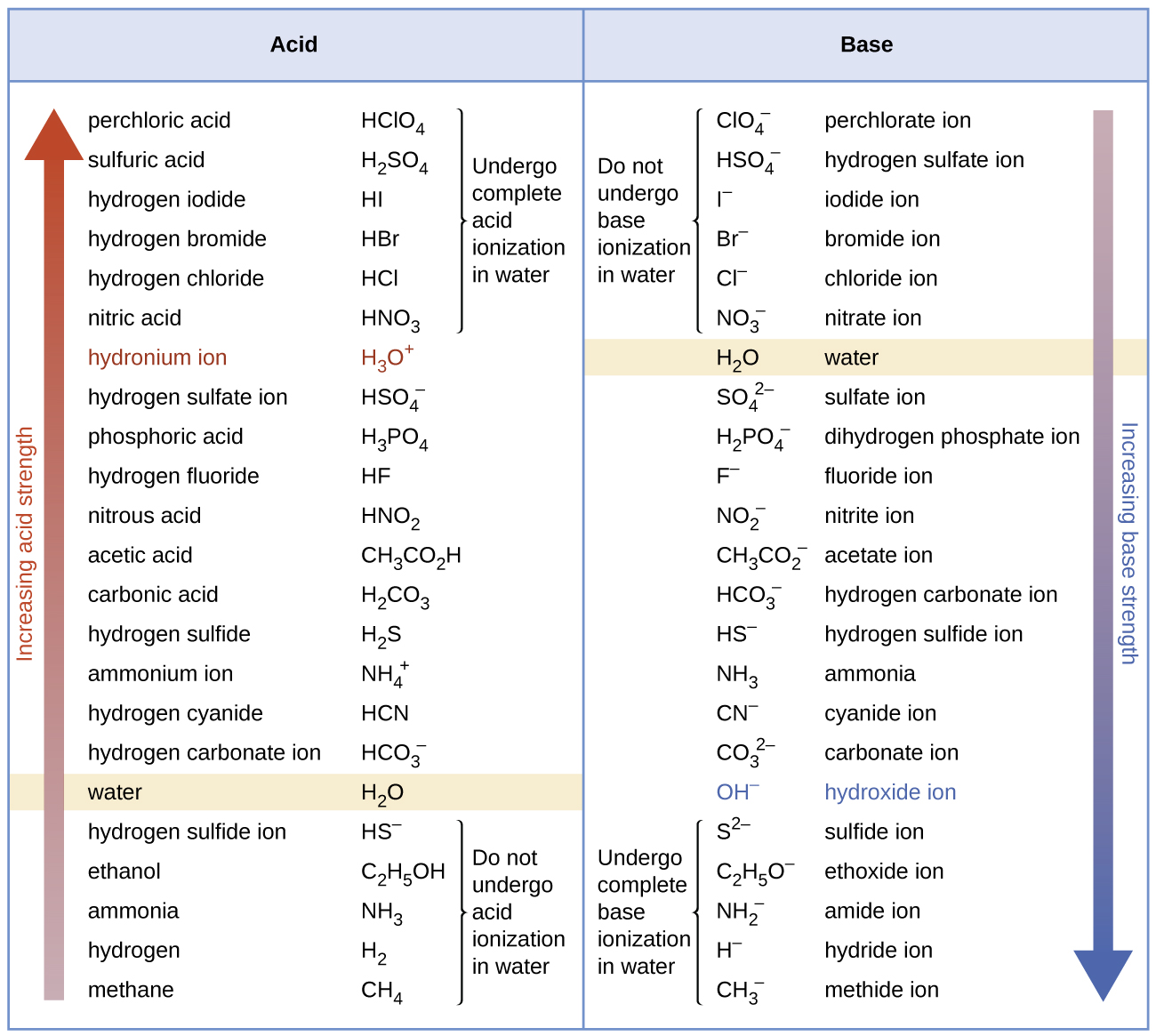

The listing of conjugate acid–base pairs shown in Figure 14.8 is arranged to show the relative strength of each species as compared with water, whose entries are highlighted in each of the table’s columns. In the acid column, those species listed below water are weaker acids than water. These species do not undergo acid ionization in water; they are not Bronsted-Lowry acids. All the species listed above water are stronger acids, transferring protons to water to some extent when dissolved in an aqueous solution to generate hydronium ions. Species above water but below hydronium ion are weak acids, undergoing partial acid ionization, wheres those above hydronium ion are strong acids that are completely ionized in aqueous solution.

The right column of Figure 14.8 lists a number of substances in order of increasing base strength from top to bottom. Following the same logic as for the left column, species listed above water are weaker bases and so they don’t undergo base ionization when dissolved in water. Species listed between water and its conjugate base, hydroxide ion, are weak bases that partially ionize. Species listed below hydroxide ion are strong bases that completely ionize in water to yield hydroxide ions (i.e., they are leveled to hydroxide). A comparison of the acid and base columns in this table supports the reciprocal relation between the strengths of conjugate acid-base pairs. For example, the conjugate bases of the strong acids (top of table) are all of negligible strength. A strong acid exhibits an immeasurably large Ka, and so its conjugate base will exhibit a Kb that is essentially zero:

strong acid: [latex]K_a \approx \infty[/latex]

A similar approach can be used to support the observation that conjugate acids of strong bases (Kb ≈ ∞) are of negligible strength (Ka ≈ 0).

Example 14.8 - Calculating Ionization Constants for Conjugate Acid-Base Pairs

Use the Kb for the nitrite ion, NO2−, to calculate the Ka for its conjugate acid.

Solution

Kb for NO2− is given in this section as 2.17 × 10−11. The conjugate acid of NO2− is HNO2; Ka for HNO2 can be calculated using the relationship:

Check Your Learning

Click here to see this problem worked through!

Acid-Base Equilibrium Calculations

The chapter on chemical equilibria introduced several types of equilibrium calculations and the various mathematical strategies that are helpful in performing them. These strategies are generally useful for equilibrium systems regardless of chemical reaction class, and so they may be effectively applied to acid-base equilibrium problems. This section presents several example exercises involving equilibrium calculations for acid-base systems.

Example 14.9 - Determination of Ka from Equilibrium Concentrations

Acetic acid is the principal ingredient in vinegar (Figure 14.10) that provides its sour taste. At equilibrium, a solution contains [CH3CO2H] = 0.0787 M and [H3O+] = [CH3CO2−] = 0.00118 M.

What is the value of Ka for acetic acid?

Solution

The relevant equilibrium equation and its equilibrium constant expression are shown below. Substitution of the provided equilibrium concentrations permits a straightforward calculation of the Ka for acetic acid.

[latex][/latex]

[latex]K_a = \frac {[H_3O^+] \, [CH_3CO_2^-]}{[CH_3CO_2H]} = \frac {(0.00118) \, (0.00118)}{0.0787} = 1.77 \times 10^{-5}[/latex]

Check Your Learning

The HSO4− ion is a weak acid used in some household cleansers:

[latex][/latex]

What is the acid ionization constant for this weak acid if an equilibrium mixture has the following composition: [H3O+] = 0.027 M; [HSO4−] = 0.29 M; and [SO42−] = 0.13 M?

Click here for the answer!

[latex]K_a = \frac {[H_3O^+] \, [SO_4^{2-}]}{[HSO_4^-]} = \frac {(0.027) \, (0.13)}{0.29} = 1.2 \times 10^{-2}[/latex]

Example 14.10 - Determination of Kb from Equilibrium Concentrations

Caffeine, C8H10N4O2, is a weak base.

What is the value of Kb for caffeine if a solution at equilibrium has [C8H10N4O2] = 0.050 M, [C8H10N4O2H+] = 5.0 × 10−3 M, and [OH−] = 2.5 × 10−3 M?

Solution

The relevant equilibrium equation and its equilibrium constant expression are shown below. Substitution of the provided equilibrium concentrations permits a straightforward calculation of the Kb for caffeine.

[latex][/latex]

[latex]K_b = \frac {[C_8H_{10}N_4O_2H^+] \, [OH^-]}{[C_8H_{10}N_4O_2]} = \frac {(5.0 \times 10^{-3}) \, (5.0 \times 10^{-3})}{0.050} = 2.5 \times 10^{-4}[/latex]

Check Your Learning

What is the equilibrium constant for the ionization of the HPO42− ion, a weak base:

if the composition of an equilibrium mixture is as follows: [OH−] = 1.3 × 10−6 M, [H2PO4−] = 0.042 M, and [HPO42−] = 0.341 M?

Click here for the answer!

[latex]K_b = \frac {[H_2PO_4^{-}] \, [OH^-]}{[HPO_4^{2-}]} = \frac {(0.042) \, (1.3 \times 10^{-6})}{0.341} = 1.6 \times 10^{-7}[/latex]

Example 14.11 - Determination of Ka or Kb from pH

The pH of a 0.0516-M solution of nitrous acid, HNO2, is 2.34. What is its Ka?

Solution

The nitrous acid concentration is that of the solution prepared in the lab; it does not account for any chemical equilibria that may be established in solution after preparation. Such concentrations are treated as “initial” values for equilibrium calculations using the ICE table approach.

The initial concentration of hydronium ion is listed as approximately zero because a small concentration of H3O+ is present (1 × 10−7 M) due to the autoionization of water. In many cases, such as all the ones presented in this chapter, this concentration is much less than that generated by ionization of the acid (or base) in question and may be neglected.

The pH is measured after equilibrium has been achieved for the nitrous acid ionization reaction, so it represents an “equilibrium” value for H3O+ in the ICE table:

| HNO2(aq) | + | H2O(l) | ⇌ | H3O+(aq) | + | NO2−(aq) | |

| I (M) | 0.0516 | -- | ~0 | 0 | |||

| C (M) | −0.0046 | (−0.0046) | +0.0046 | +0.0046 | |||

| E (M) | 0.0470 | -- | 0.0046 | 0.0046 |

Finally, calculate the value of the equilibrium constant using the data in the table:

Check Your Learning

Click here for a walkthrough of these problems!

The ionization reaction is:

NH3 (aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ NH4+(aq) + OH−(aq)

To calculate Kb, we should first determine [OH-]. We can calculate pOH:

[latex]pOH = 14 - pH = 14 - 11.612 = 2.388[/latex]

and use it to determine [OH-] at equilibrium:

[latex][OH^-] = 10^{-pOH} = 10^{-2.388} = 0.00409 M[/latex]

| NH3(aq) | + | H2O(l) | ⇌ | NH4+(aq) | + | OH−(aq) | |

| I (M) | 0.950 | -- | 0 | ~0 | |||

| C (M) | −0.00409 | (−0.0046) | +0.00409 | +0.00409 | |||

| E (M) | 0.946 | -- | 0.00409 | 0.00409 |

Finally, calculate the value of the equilibrium constant using the data in the table:

Example 14.12 - Calculating Equilibrium Concentrations in a Weak Acid Solution

Formic acid, HCO2H, is one irritant that causes the body’s reaction to some ant bites and stings (Figure 14.11).

What is the concentration of hydronium ion and the pH of a 0.534-M solution of formic acid?

HCO2H(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + HCO2−(aq) Ka = 1.8 × 10−4

Solution

The ICE table for this system is:

| HCO2H(aq) | + | H2O(l) | ⇌ | H3O+(aq) | + | HCO2−(aq) | |

| I (M) | 0.534 | -- | ~0 | 0 | |||

| C (M) | −x | (−x) | +x | +x | |||

| E (M) | 0.534 − x | -- | x | x |

Substituting the equilibrium concentration terms into the Ka expression gives:

The relatively large initial concentration and small equilibrium constant permits the simplifying assumption that x will be much lesser than 0.534, and so the equation becomes:

Check Your Learning

Click here to see walkthroughs for these problems!

The ICE table for this system is:

| CH3CO2H(aq) | + | H2O(l) | ⇌ | H3O+(aq) | + | CH3CO2−(aq) | |

| I (M) | 0.100 | -- | ~0 | 0 | |||

| C (M) | −x | (−x) | +x | +x | |||

| E (M) | 0.100 − x | -- | x | x |

Substituting the equilibrium concentration terms into the Ka expression gives:

The relatively large initial concentration and small equilibrium constant permits the "small x" approximation:

Example 14.13 - Calculating Equilibrium Concentrations in a Weak Base Solution

Find the concentration of hydroxide ion, the pOH, and the pH of a 0.25-M solution of trimethylamine, a weak base:

Solution

The ICE table for this system is:

| (CH3)3N(aq) | + | H2O(l) | ⇌ | (CH3)3NH+(aq) | + | OH−(aq) | |

| I (M) | 0.25 | -- | 0 | ~0 | |||

| C (M) | −x | (−x) | +x | +x | |||

| E (M) | 0.25 − x | -- | x | x |

Substituting the equilibrium concentration terms into the Kb expression gives:

As defined in the ICE table, x is equal to the equilibrium concentration of hydroxide ion:

[latex][OH^-] = x = 4.0 \times 10^{-3} \: M[/latex]

The pOH is calculated to be:

[latex][/latex]

permits the computation of pH:

Click here to see walkthroughs for these problems!

The ICE table for this system is:

| NH3(aq) | + | H2O(l) | ⇌ | NH4+(aq) | + | OH−(aq) | |

| I (M) | 0.0325 | -- | 0 | ~0 | |||

| C (M) | −x | (−x) | +x | +x | |||

| E (M) | 0.0325 − x | -- | x | x |

Substituting the equilibrium concentration terms into the Kb expression gives:

The pOH is calculated to be:

In some cases, the strength of the weak acid or base and its initial concentration result in an appreciable ionization. Though the ICE strategy remains effective for these systems, the algebra is a bit more involved because the simplifying assumption that x is negligible cannot be made. Calculations of this sort are demonstrated in Example 14.14 below.

Example 14.14 - Calculating Equilibrium Concentrations without Simplifying Assumptions

Sodium bisulfate, NaHSO4, is used in some household cleansers as a source of the HSO4− ion, a weak acid. What is the pH of a 0.50-M solution of HSO4−?

Solution

The ICE table for this system is:

| HSO4−(aq) | + | H2O(l) | ⇌ | H3O+(aq) | + | SO42−(aq) | |

| I (M) | 0.50 | -- | ~0 | 0 | |||

| C (M) | −x | (−x) | +x | +x | |||

| E (M) | 0.50 − x | -- | x | x |

Substituting the equilibrium concentration terms into the Ka expression gives:

[latex][/latex]

[latex]x = [H_3O^+] = 0.072 \: M[/latex]

[latex]\text {pH} = - \log {[H_3O^+]} = - \log (0.072) = 1.14[/latex]

Check Your Learning

Calculate the pH in a 0.010-M solution of caffeine, a weak base:

Click here to see the answer!

The ICE table for this system is:

| C8H10N4O2(aq) | + | H2O(l) | ⇌ | C8H10N4O2H+(aq) | + | OH−(aq) | |

| I (M) | 0.010 | -- | 0 | ~0 | |||

| C (M) | −x | (−x) | +x | +x | |||

| E (M) | 0.010 − x | -- | x | x |

Substituting the equilibrium concentration terms into the Kb expression gives: