Chapter 8 Advanced Theories of Covalent Bonding

8.3 Multiple Bonds

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe multiple covalent bonding in terms of atomic orbital overlap

- Relate the concept of resonance to π-bonding and electron delocalization

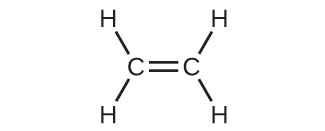

The hybrid orbital model appears to account well for the geometry of molecules involving single covalent bonds. Is it also capable of describing molecules containing double and triple bonds? We have already discussed that multiple bonds consist of σ and π bonds. Next we can consider how we visualize these components and how they relate to hybrid orbitals. The Lewis structure of ethene, C2H4, shows us that each carbon atom is surrounded by one other carbon atom and two hydrogen atoms.

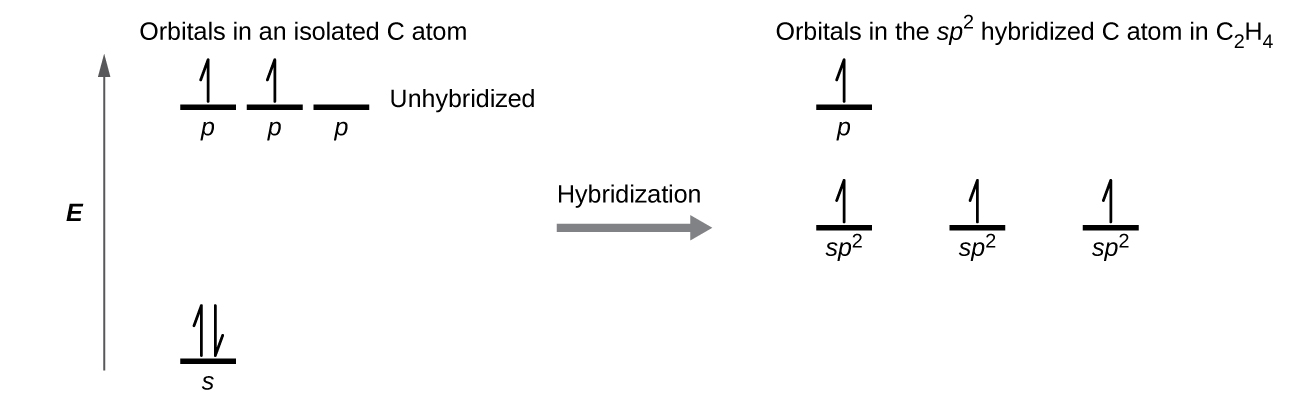

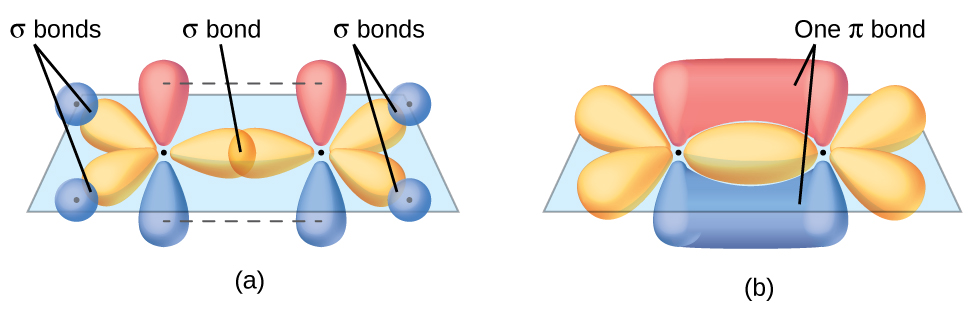

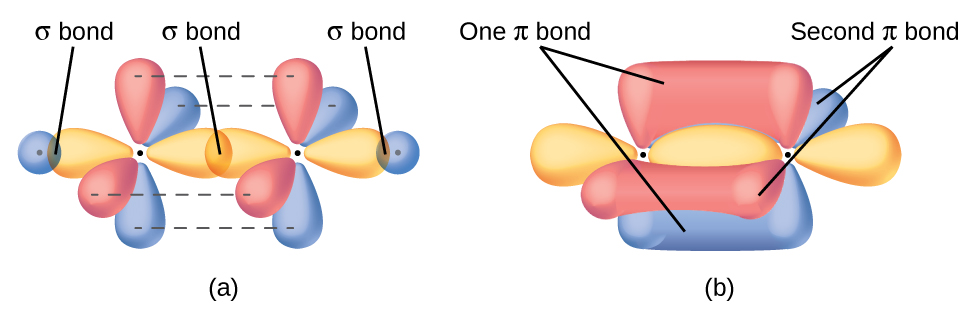

The three bonding regions form a trigonal planar electron-pair geometry. Thus we expect the σ bonds from each carbon atom are formed using a set of sp2 hybrid orbitals that result from hybridization of two of the 2p orbitals and the 2s orbital (Figure 8.23). These orbitals form the C–H single bonds and the σ bond in the C=C double bond (Figure 8.24). The π bond in the C=C double bond results from the overlap of the third (remaining) 2p orbital on each carbon atom that is not involved in hybridization. This unhybridized p orbital (lobes shown in red and blue in Figure 8.24) is perpendicular to the plane of the sp2 hybrid orbitals. Thus the unhybridized 2p orbitals overlap in a side-by-side fashion, above and below the internuclear axis (Figure 8.24) and form a π bond.

In an ethene molecule, the four hydrogen atoms and the two carbon atoms are all in the same plane. If the two planes of sp2 hybrid orbitals tilted relative to each other, the p orbitals would not be oriented to overlap efficiently to create the π bond. The planar configuration for the ethene molecule occurs because it is the most stable bonding arrangement. This is a significant difference between σ and π bonds; rotation around single (σ) bonds occurs easily because the end-to-end orbital overlap does not depend on the relative orientation of the orbitals on each atom in the bond. In other words, rotation around the internuclear axis does not change the extent to which the σ bonding orbitals overlap because the bonding electron density is symmetric about the axis. Rotation about the internuclear axis is much more difficult for multiple bonds; however, this would drastically alter the off-axis overlap of the π bonding orbitals, essentially breaking the π bond.

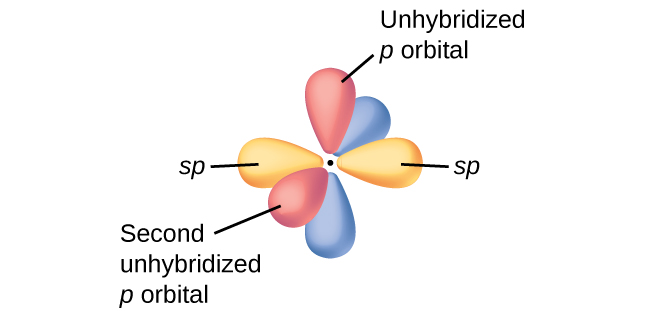

In molecules with sp hybrid orbitals, two unhybridized p orbitals remain on the atom (Figure 8.25). We find this situation in acetylene, H−C≡C−H, which is a linear molecule. The sp hybrid orbitals of the two carbon atoms overlap end to end to form a σ bond between the carbon atoms (Figure 8.26). The remaining sp orbitals form σ bonds with hydrogen atoms. The two unhybridized p orbitals per carbon are positioned such that they overlap side by side and, hence, form two π bonds. The two carbon atoms of acetylene are thus bound together by one σ bond and two π bonds, giving a triple bond.

Hybridization involves only σ bonds, lone pairs of electrons, and single unpaired electrons (radicals). Structures that account for these features describe the correct hybridization of the atoms. However, many structures also include resonance forms. Remember that resonance forms occur when various arrangements of π bonds are possible. Since the arrangement of π bonds involves only the unhybridized orbitals, resonance does not influence the assignment of hybridization.

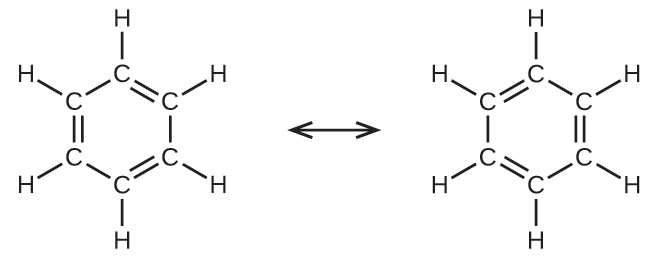

For example, molecule benzene has two resonance forms (Figure 8.27). We can use either of these forms to determine that each of the carbon atoms is bonded to three other atoms with no lone pairs, so the correct hybridization is sp2. The electrons in the unhybridized p orbitals form π bonds. Neither resonance structure completely describes the electrons in the π bonds. They are not located in one position or the other but in reality are delocalized throughout the ring. Valence bond theory does not easily address delocalization. Bonding in molecules with resonance forms is better described by molecular orbital theory. (See the next module.)

Example 8.4. Assignment of Hybridization Involving Resonance

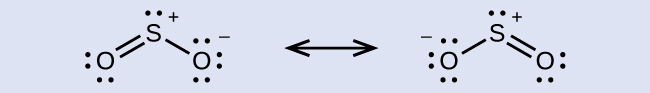

Some acid rain results from the reaction of sulfur dioxide with atmospheric water vapor, followed by the formation of sulfuric acid. Sulfur dioxide, SO2, is a major component of volcanic gases as well as a product of the combustion of sulfur-containing coal. What is the hybridization of the S atom in SO2?

Solution

The resonance structures of SO2 are:

The sulfur atom is surrounded by two bonds and one lone pair of electrons in either resonance structure. Therefore, the electron-pair geometry is trigonal planar, and the hybridization of the sulfur atom is sp2.

Check Your Learning

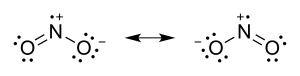

Another acid in acid rain is nitric acid, HNO3, which is produced by the reaction of nitrogen dioxide, NO2, with atmospheric water vapor.

What is the Lewis structure of NO2?

What is the hybridization of the central N atom?

sp2

Note that the lone electron on nitrogen occupies a hybridized orbital—just like a lone pair would.