Chapter 5 Thermochemistry

5.3 Enthalpy and Thermochemical Equations

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- State the first law of thermodynamics

- Define enthalpy and explain its classification as a state function

- Write and balance thermochemical equations

Thermochemistry is a branch of chemical thermodynamics, the science that deals with the relationships between heat, work, and other forms of energy in the context of chemical and physical processes. As we concentrate on thermochemistry in this chapter, we need to consider some widely used concepts of thermodynamics.

Substances act as reservoirs of energy, meaning that energy can be added to them or removed from them. Energy is stored in a substance when the kinetic energy of its atoms or molecules is raised. The greater kinetic energy may be in the form of increased translations (travel or straight-line motions), vibrations, or rotations of the atoms or molecules. When thermal energy is lost, the intensities of these motions decrease and the kinetic energy falls. The total of all possible kinds of energy present in a substance is called the internal energy (U), sometimes symbolized as E.

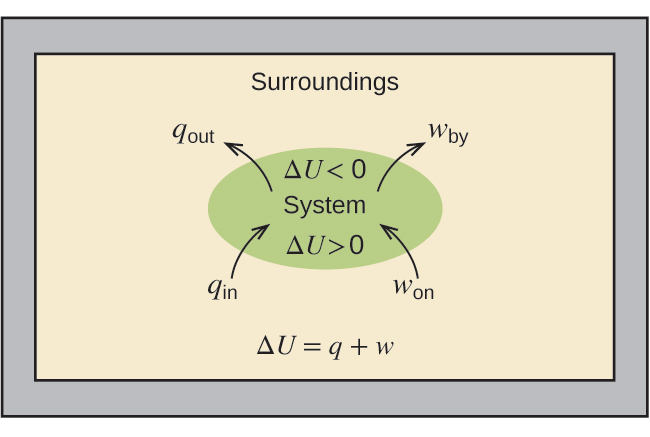

As a system undergoes a change, its internal energy can change, and energy can be transferred from the system to the surroundings, or from the surroundings to the system. Energy is transferred into a system when it absorbs heat (q) from the surroundings or when the surroundings do work (w) on the system. For example, energy is transferred into room-temperature metal wire if it is immersed in hot water (the wire absorbs heat from the water), or if you rapidly bend the wire back and forth (the wire becomes warmer because of the work done on it). Both processes increase the internal energy of the wire, which is reflected in an increase in the wire’s temperature. Conversely, energy is transferred out of a system when heat is lost from the system, or when the system does work on the surroundings.

The relationship between internal energy, heat, and work can be represented by the equation:

A type of work called expansion work (or pressure-volume work) occurs when a system pushes back the surroundings against a restraining pressure, or when the surroundings compress the system. An example of this occurs during the operation of an internal combustion engine. The reaction of gasoline and oxygen is exothermic. Some of this energy is given off as heat, and some does work pushing the piston in the cylinder. The substances involved in the reaction are the system, and the engine and the rest of the universe are the surroundings. The system loses energy by both heating and doing work on the surroundings, and its internal energy decreases. (The engine is able to keep the car moving because this process is repeated many times per second while the engine is running.) We will consider how to determine the amount of work involved in a chemical or physical change in the chapter on thermodynamics.

Link to Learning

This view of an internal combustion engine illustrates the conversion of energy produced by the exothermic combustion reaction of a fuel such as gasoline into energy of motion.

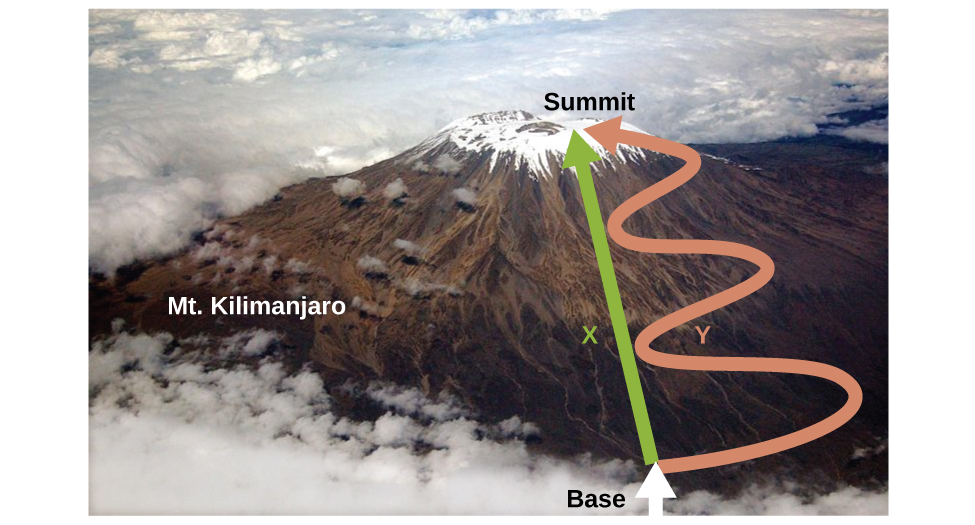

As discussed, the relationship between internal energy, heat, and work can be represented as ΔU = q + w. Internal energy is an example of a state function (or state variable), whereas heat and work are not state functions. The value of a state function depends only on the state that a system is in, and not on how that state is reached. If a quantity is not a state function, then its value does depend on how the state is reached. An example of a state function is altitude or elevation. If you stand on the summit of Mt. Kilimanjaro, you are at an altitude of 5895 m, and it does not matter whether you hiked there or parachuted there. The distance you traveled to the top of Kilimanjaro, however, is not a state function. You could climb to the summit by a direct route or by a more roundabout, circuitous path (Figure 5.21). The distances traveled would differ (distance is not a state function) but the elevation reached would be the same (altitude is a state function).

Chemists ordinarily use a property known as enthalpy (H) to describe the thermodynamics of chemical and physical processes. Enthalpy is defined as the sum of a system’s internal energy (U) and the mathematical product of its pressure (P) and volume (V):

Enthalpy is also a state function. Enthalpy values for specific substances cannot be measured directly; only enthalpy changes for chemical or physical processes can be determined. For processes that take place at constant pressure (a common condition for many chemical and physical changes), the enthalpy change (ΔH) is:

The mathematical product PΔV represents work (w), namely, expansion or pressure-volume work as noted. By their definitions, the arithmetic signs of ΔV and w will always be opposite:

Substituting this equation and the definition of internal energy into the enthalpy-change equation yields:

The heat given off when you operate a Bunsen burner is equal to the enthalpy change of the methane combustion reaction that takes place, since it occurs at the essentially constant pressure of the atmosphere. On the other hand, the heat produced by a reaction measured in a bomb calorimeter (Figure 5.18) is not equal to ΔH because the closed, constant-volume metal container prevents the pressure from remaining constant (it may increase or decrease if the reaction yields increased or decreased amounts of gaseous species). Chemists usually perform experiments under normal atmospheric conditions, at constant external pressure with q = ΔH, which makes enthalpy the most convenient choice for determining heat changes for chemical reactions.

The following conventions apply when using ΔH:

- A negative value of an enthalpy change, ΔH < 0, indicates an exothermic reaction

- A positive value, ΔH > 0, indicates an endothermic reaction

- If the direction of a chemical equation is reversed, the arithmetic sign of its ΔH is changed (a process that is endothermic in one direction is exothermic in the opposite direction).

Chemists use a thermochemical equation to represent the changes in both matter and energy. In a thermochemical equation, the enthalpy change of a reaction is shown as a ΔH value following the equation for the reaction. This ΔH value indicates the amount of heat associated with the reaction involving the number of moles of reactants and products as shown in the chemical equation. For example, consider this equation:

This equation indicates that when 1 mole of hydrogen gas and 12 mole of oxygen gas at some temperature and pressure change to 1 mole of liquid water at the same temperature and pressure, 286 kJ of heat are released to the surroundings. If the coefficients of the chemical equation are multiplied by some factor, the enthalpy change must be multiplied by that same factor (ΔH is an extensive property):

1/2 H2(g) + 1/4 O2(g) → 1/2 H2O(l) ΔH = 1/2 (−286 kJ) = −143 kJ

The enthalpy change of a reaction depends on the physical states of the reactants and products, so these must be shown. As shown above, when 1 mole of hydrogen gas and 12 mole of oxygen gas change to 1 mole of liquid water at the same temperature and pressure, 286 kJ of heat are released. If gaseous water forms instead, only 242 kJ of heat are released.

Example 5.8 – Writing Thermochemical Equations

When 0.0500 mol of HCl(aq) reacts with 0.0500 mol of NaOH(aq) to form 0.0500 mol of NaCl(aq), 2.9 kJ of heat are produced. Write a balanced thermochemical equation for the reaction of one mole of HCl.

Solution

For the reaction of 0.0500 mol acid (HCl), q = −2.9 kJ. The reactants are provided in stoichiometric amounts (same molar ratio as in the balanced equation), and so the amount of acid may be used to calculate a molar enthalpy change. Since ΔH is an extensive property, it is proportional to the amount of acid neutralized:

The thermochemical equation is then

Check Your Learning

Be sure to take both stoichiometry and limiting reactants into account when determining the ΔH for a chemical reaction.

Example 5.9 – Writing Thermochemical Equations

A gummy bear contains 2.67 g sucrose, C12H22O11. When it reacts with 7.19 g potassium chlorate, KClO3, 43.7 kJ of heat are produced. Write a thermochemical equation for the reaction of one mole of sucrose:

Solution

Unlike the previous example exercise, this one does not involve the reaction of stoichiometric amounts of reactants, and so the limiting reactant must be identified (it limits the yield of the reaction and the amount of thermal energy produced or consumed).

The provided amounts of the two reactants are

The provided molar ratio of perchlorate-to-sucrose is then

The balanced equation indicates 8 mol KClO3 are required for reaction with 1 mol C12H22O11. Since the provided amount of KClO3 is less than the stoichiometric amount, it is the limiting reactant and may be used to compute the enthalpy change:

Because the equation, as written, represents the reaction of 8 mol KClO3, the enthalpy change is

The enthalpy change for this reaction is −5960 kJ, and the thermochemical equation is:

C12H22O11(aq) + 8 KClO3(aq) → 12 CO2(g) + 11 H2O(l) + 8 KCl(aq) ΔH = −5960 kJ

Check Your Learning

Enthalpy changes are typically tabulated for reactions in which both the reactants and products are at the same conditions. A standard state is a commonly accepted set of conditions used as a reference point for the determination of properties under other different conditions. For chemists, the IUPAC standard state refers to materials under a pressure of 1 bar and solutions at 1 M, and does not specify a temperature. Many thermochemical tables list values with a standard state of 1 atm. Because the ΔH of a reaction changes very little with such small changes in pressure (1 bar = 0.987 atm), ΔH values (except for the most precisely measured values) are essentially the same under both sets of standard conditions. We will include a superscripted “o” in the enthalpy change symbol to designate standard state. Since the usual (but not technically standard) temperature is 298.15 K, this temperature will be assumed unless some other temperature is specified. Thus, the symbol (ΔH°) is used to indicate an enthalpy change for a process occurring under these conditions. (The symbol ΔH is used to indicate an enthalpy change for a reaction occurring under nonstandard conditions.)

The enthalpy changes for many types of chemical and physical processes are available in the reference literature, including those for combustion reactions, phase transitions, and formation reactions. As we discuss these quantities, it is important to pay attention to the extensive nature of enthalpy and enthalpy changes. Since the enthalpy change for a given reaction is proportional to the amounts of substances involved, it may be reported on that basis (i.e., as the ΔH for specific amounts of reactants). However, we often find it more useful to divide one extensive property (ΔH) by another (amount of substance), and report a per-amount intensive value of ΔH, often “normalized” to a per-mole basis. (Note that this is similar to determining the intensive property specific heat from the extensive property heat capacity, as seen previously.)

Standard Enthalpy of Combustion

Standard enthalpy of combustion (ΔHc°) is the enthalpy change when 1 mole of a substance burns (combines vigorously with oxygen) under standard state conditions; it is sometimes called “heat of combustion.” For example, the enthalpy of combustion of ethanol, −1366.8 kJ/mol, is the amount of heat produced when one mole of ethanol undergoes complete combustion at 25°C and 1 atmosphere pressure, yielding products also at 25°C and 1 atm.

Enthalpies of combustion for many substances have been measured; a few of these are listed in Table 5.2. Many readily available substances with large enthalpies of combustion are used as fuels, including hydrogen, carbon (as coal or charcoal), and hydrocarbons (compounds containing only hydrogen and carbon), such as methane, propane, and the major components of gasoline.

|

Substance |

Combustion Reaction |

Enthalpy of Combustion, ΔHc° (kJ/mol at 25°C) |

|

carbon |

C(s) + O2(g) → CO2(g)

|

−393.5 |

|

hydrogen |

H2(g) + 12 O2(g) → H2O(l)

|

−285.8 |

|

magnesium |

Mg(s) + 12 O2(g) → MgO(s)

|

−601.6 |

|

sulfur |

S(s) + O2(g) → SO2(g)

|

−296.8 |

|

carbon monoxide |

CO(g) + 12 O2(g) → CO2(g)

|

−283.0 |

|

methane |

CH4(g) + 2 O2(g) → CO2(g) + 2 H2O(l)

|

−890.8 |

|

acetylene |

C2H2(g) + 5/2 O2(g) → 2 CO2(g) + H2O(l)

|

−1301.1 |

|

ethanol |

C2H5OH(l) + 3 O2(g) → 2 CO2(g) + 3 H2O(l)

|

−1366.8 |

|

methanol |

CH3OH(l) + 3/2 O2(g) → CO2(g) + 2 H2O(l)

|

−726.1 |

|

isooctane |

C8H18(l) + 25/2 O2(g) → 8 CO2(g) + 9 H2O(l)

|

−5461 |

Example 5.10 – Using Enthalpy of Combustion

As Figure 5.22 suggests, the combustion of gasoline is a highly exothermic process. Let us determine the approximate amount of heat produced by burning 1.00 L of gasoline, assuming the enthalpy of combustion of gasoline is the same as that of isooctane, a common component of gasoline. The density of isooctane is 0.692 g/mL.

Solution

Starting with a known amount (1.00 L of isooctane), we can perform conversions between units until we arrive at the desired amount of heat or energy. The enthalpy of combustion of isooctane provides one of the necessary conversions. Table 5.2 gives this value as −5460 kJ per 1 mole of isooctane (C8H18).

Using these data,

The combustion of 1.00 L of isooctane produces 33,100 kJ of heat. (This amount of energy is enough to melt 99.2 kg, or about 218 lbs, of ice.)

Note: If you do this calculation one step at a time, you will retrieve the same answer:

Check Your Learning

Chemistry in Everyday Life

Emerging Algae-Based Energy Technologies (Biofuels)

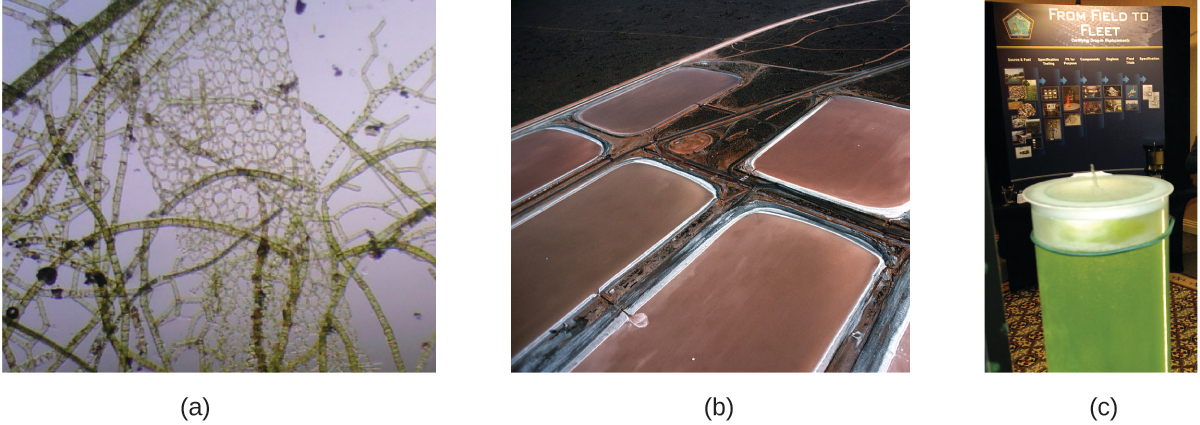

As reserves of fossil fuels diminish and become more costly to extract, the search is ongoing for replacement fuel sources for the future. Among the most promising biofuels are those derived from algae (Figure 5.23). The species of algae used are nontoxic, biodegradable, and among the world’s fastest growing organisms. About 50% of algal weight is oil, which can be readily converted into fuel such as biodiesel. Algae can yield 26,000 gallons of biofuel per hectare—much more energy per acre than other crops. Some strains of algae can flourish in brackish water that is not usable for growing other crops. Algae can produce biodiesel, biogasoline, ethanol, butanol, methane, and even jet fuel.

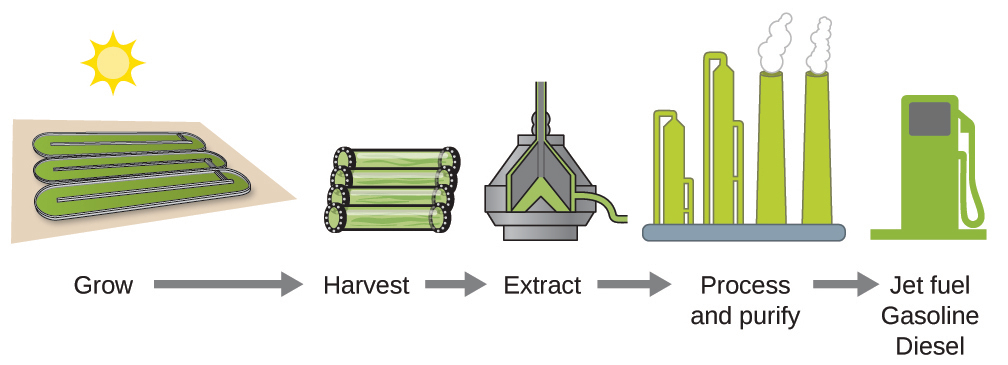

According to the US Department of Energy, only 39,000 square kilometers (about 0.4% of the land mass of the US or less than 1/7 of the area used to grow corn) can produce enough algal fuel to replace all the petroleum-based fuel used in the US. The cost of algal fuels is becoming more competitive—for instance, the US Air Force is producing jet fuel from algae at a total cost of under $5 per gallon.[1] The process used to produce algal fuel is as follows: grow the algae (which use sunlight as their energy source and CO2 as a raw material); harvest the algae; extract the fuel compounds (or precursor compounds); process as necessary (e.g., perform a transesterification reaction to make biodiesel); purify; and distribute (Figure 5.24).

Link to Learning

Click here to learn more about the process of creating algae biofuel.

Media Attributions

- Car Arson

- For more on algal fuel, see http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2010/feb/13/algae-solve-pentagon-fuel-problem. ↵