Building Your Garden: Tools and Interactivity

Accessibility, UDL, and Your Tools

Theresa Huff

Learning Objectives

- Consider the accessibility of tools you plan to use

- Identify key principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

Accessibility of the Tool

Tools can be cool and useful, and it’s very tempting to adopt a tool and begin to use it in your classroom or in your OER without first considering if all your learners can actually use it. As you look for and play with potential tools, take a beat to ask

- Will this work for students using a screen reader?

- Is there a cost involved for learners?

- Will it work on all devices?

These and other questions will help guide you in deciding on whether or not the tool is a good choice. We have provided you with guides to the three main tools covered in this chapter, but you will want to review any other tool’s accessibility before deciding to use it.

Universal Design for Learning

For those that aren’t familiar with Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and the companion Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) framework tool, this section offers a brief explanation and guidance on how to use CAST’s interactive tool.

Attention: You Have Options!

On this page, you can choose how you would prefer to learn about UDL. You can view and listen to the video, interact with the H5P pop-up, or you can read the text on the page and interact with the H5Ps throughout the page.

What's This Tool - H5P Interactive Video

Introduction

What is UDL? Where did the idea come from? What’s the goal of UDL and how can its framework be used by educators? In this section, we’ll answer these questions and hopefully help you feel more confident in how to use the amazing tool known as the Universal Design Framework.

Concept of Universal Design

The term Universal Design (UD) was introduced in the 1980s by architect Ronald Mace. Originally, UD referred to “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design” (Connell et al., 1997). What did this mean?

Architecture House Entrance by cocparisienne is licensed under a CCO 1.0 Deed.

Well, consider the barriers presented when entering a building that has steps that lead up to a door with handles. Who might have difficulty accessing such a building? You might say someone who is uses a wheelchair might find the steps a barrier … but so might a person pushing a stroller. The handles on the door might be a barrier for someone who has limited control over their arms … but so might someone with their hands full.”

8607282541_56e9ccffb7_z.jpg by czelticgirl is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

Compare that with a building whose entrance is at ground-level with doors that open automatically. Who might have difficulty navigating this building? The answer is … very few people. UD tried to find ways of designing architecture that would remove barriers and make buildings, among other things, physically accessible for everyone.

But accessibility barriers don’t just exist in architecture. They are built into learning environment, too. Just like those stairs pose barriers in the built environment, there are many barriers to learning in education. And where UD worked to remove physical, architectural barriers, UDL was created to remove barriers in the field of education.

A UDL approach includes paradigm shifts: from a deficit mindset to neurodiversity; from singular accommodations to universally accessible scaffolds and supports; from a teacher-centric view to a student-centered approach centered on student agency. By removing the barriers, we improve access for all learners.

Universal Design for Learning

Based on cognitive neuroscience research, the UDL framework was created by David Rose, Anne Meyer, and more at the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) (Meyer, et al. 2002; Rose, Rouhani, et al., 2013; Rose, 2016). The CAST organization exists to eliminate the barriers to learning and support the development of expert learners. They seek to address issues of accessibility, which includes diversity, equity, and inclusion.

We educators often design our curriculum for the “average” student. By doing so, we accept the fact that some students’ needs will not be met. While this was accepted for years, this practice doesn’t actually support marginalized students. In fact, by design, it sets up historically underserved students to continue to be marginalized.

UDL is based on the understanding that all learners vary, and that there is no “average student.” Since we can’t plan for every variability of every learner, UDL focuses on designing, developing, and delivering curriculum with built-in options that ensure everyone’s needs can be met. By designing curriculum that works for all learners, the learning environment becomes more equitable, accessible, and inclusive for all diverse student populations.

To help support educators toward this end, CAST created the UDL Guidelines, a framework to provide educators, curriculum developers, researchers, parents, and others the strategies for implementing UDL in a learning environment. The UDL guidelines offer concrete ideas for curriculum design, development and delivery that ensure all learners can be supported.

Take a look at the Cast UDL Guidelines at the CAST website.

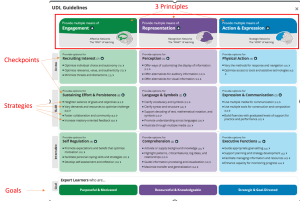

UDL Guidelines

Checkpoints, strategies, and goals for achieving the three principles of UDL.

The UDL Guidelines are broken down into three principles, based on three types of neural networks. Each principle has three checkpoints, depending on the educational goal of the learner. Each principle also leads to a different learner-outcome or goal. Collectively, the three goals make up the definition of an expert learner. CAST’s UDL Guidelines on their website are also interactive, so that educators and designers can drill down for more details and ideas for implementation.

Networks

UDL Guidelines are based on the three primary brain networks:

- Affective networks: the “why” of learning

- Recognition networks: the “what” of learning

- Strategic networks: the “how” of learning

When educators create learning experiences that activate these three broad learning networks, learners are moved towards the goal of expert learning. In addition, the UDL framework reminds us that all brains are variable and that the old idea of “learning styles” do not actually exist. Instead, we know that each brain is processing information in complex and variable interactions between the various networks of the brain.

Principles

CAST has identified a series of principles to guide design, development, and delivery that address each of the three brain networks:

- Multiple means of engagement (addresses the Why of learning)

- Multiple means of representation (addresses the What of learning)

- Multiple means of action and expression (addresses the How of learning)

CAST’s UDL Graphic Organizer includes each of these networks and principles as headings over columns of strategies that support the lighting up of each of these neural networks.

Checkpoints

Each network contains checkpoints that emphasize learner diversity that could either present barriers to, or opportunities for, learning. There are three for each network making nine in total. The checkpoints for each network are as follows:

Now, these guidelines are not prescriptive. But they do offer informed suggestions that can be used in any program, course or learning environment to support masterful learning and accurate assessment for all learners.

Just as we are still learning about the brain, and the ways we all learn, the UDL Guidelines are consistently informed by user feedback and ongoing research, meaning the guidelines used in UDL have been revised a number of times.

UDL in Practice

So, what does this actually look like in practice? Remember, the UDL Framework is not prescriptive, but it can provide educators and designers some concrete ideas for designing the learning. For example, let’s say a teacher is trying to get their students more engaged in an online class. They could provide multiple ways for students to access the learning. Recruiting interest or thinking about what interests the students would be a great place to build engagement. Some strategies suggested by the checkpoints include starting with giving students choice.

Below, you will find multiple practical examples of supporting UDL in your own OER under each of the UDL Guidelines.

Examples of UDL in your OER

Multiple Means of Engagement

- Optimize choice and autonomy by offering different ways for students to engage with your content.

- Example: In this page of the OERFSJ Faculty Handbook, you are given the choice of either viewing a video that covers the content or reading the content on the page.

- Foster collaboration, interdependence, and collective learning in your OER.

- Example: Guide students to use Hypothes.is or another annotating tool to foster discussions as they read your OER.

- Promote individual and collective reflection.

- Example: Use one of the H5P types that support reflection in your OER to allow students to reflect individually on what they learned from your OER.

Multiple Means of Representation

- Represent a diversity of perspectives and identities in authentic ways.

- Example: Your work towards integrating DEIA into your OER supports this. Refer to the Introduction to DEIA in OER for Social Justice chapter.

- Illustrate through multiple media.

- Example: Use more than text in your OER. Consider adding illustrations, a video, an interactive, an image, or another type of graphic.

- Maximize transfer and generalization

- Example: Help scaffold the learning in your OER by adding checklists, templates, reviews of foundational skills using H5P, examples, and using the colorful Textboxes to review key information.

Multiple Means of Action and Expression

- Optimize access to accessible materials and accessible technologies and tools

- Example: Your work towards ensuring your OER is fully accessible supports this. Refer to the Accessibility in Your OER chapter.

- Allow students to use multiple media and tools for communication

- Example: Provide embedded tools in your OER that allow students to interact with and learn creatively such as H5P for Interactive Content, simulations, or other embeddable interactives unique to your field.

- Organize information and resources

- Example: Provide uploaded templates and graphic organizers in your OER for students to download and use. Consistently use the same textbox in the same place in your OER chapters for learning objectives, interactive review of the content, and helpful tips and checklists. Use the H5P Cornell Notes or H5P Structure Strip to guide students in taking notes.

CAST (2024). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 3.0. Retrieved from https://udlguidelines.cast.org

When we look deeper at the embedded suggestions on the CAST website, CAST has given some more specific examples for educators such as allowing leaners autonomy where possible and allowing learners to set their own goals. This likely will look different for different age groups.

For an elementary student, this might look like having a student create a chart to reach their identified goal. But for an adult student, it might look like a discussion post at the beginning of a course where they share why they took the course and what they hope to achieve from it. In an organization, it might look like a professional documenting their professional goals annually and sharing them with their team.

Note that the UDL Framework not only shows guidelines, principles, and checkpoints that are organized by what we want our learners to do, but they are also aligned with the three parts of the UDL goals for creating expert learners. By engaging our learners, we create expert learners who are purposeful and motivated. By offering representation in the learning, we create expert learners who are resourceful and knowledgeable. And by offering ways for learners to act and express themselves, we create expert learners who are strategic and goal-oriented. So, that is yet another way educators can use the UDL Framework — by looking at these end goals, choosing one end goal they want to work toward, and working back up the framework to find strategies to reach those end goals.

Getting Started

“UDL is really just ‘plus-one’ thinking. For every interaction that learners have now — with the materials, yes, but also with each other, with instructors and with the wider world — provide one more way for that interaction to happen.” Thomas TobinYou might feel a bit overwhelmed with all the possibilities, guidance, and uses for the UDL Framework. How do you integrate all 3 Guidelines, 9 Principles, and even more Checkpoints? But, as UDL educator and author Thomas Tobin explains, UDL isn’t about applying all of these pieces. Rather it is a “plus-one approach”.

The ‘plus-one’ approach helps to take what otherwise might look like an insurmountable amount of effort and break it down into manageable, approachable chunks. It also helps people to determine where to start applying the UDL framework so they can address current challenges and pain points in their interactions.

So, just start by finding one current challenge you are having, identifying one strategy using the UDL Framework to address that challenge, and implement that one strategy. Ta-da! You’re on your way!

Take a minute to review the key takeaways about using UDL with the H5P Quiz below.

Choosing your OER Tools with UDL in Mind

Later in this chapter, you will find a variety of different tools to consider using in your own OER. Throughout discussions and examples of each tool, you will find information about how each support UDL.

Additional Resources

- Designing for inclusion (critical digital pedagogy as disability justice)

- Bonawitz, K. Disability Inclusion in Higher Education, Teaching in Higher Ed

- Sathy, V. and Hogan, K. Inclusive Teaching, Teaching in Higher Ed

Resources

“Universal Design for Learning: A Framework” by Theresa Huff is licensed with a CC BY-4.0.

Why Focus on Engagement?

Student engagement is defined as “the student’s psychological investment in and effort directed toward learning, understanding, or mastering the knowledge, skills, or crafts that academic work is intended to promote” (Newman et al, 1992, p. 12). An engaged learner tends to be a more satisfied, motivated, less lonely, and better performing learner (Banna et al., 2015; Martin & Bolliger, 2018).

Since engaging learners is so important, we want to be sure the tools we choose to use in our OER support engagement. And while we hope to engage learners with these tools, we want to do so with wisdom. Not every piece of content needs to be interactive, or we risk distracting or overwhelming our learners (Clark & Meyer, 2008).

Engagement Strategies

Moore (1993) proposed three types of student interactivity in instruction where increasing engagement might occur: learner-to-learner, learner-to-instructor, and learner-to-content. For each type of interaction, we offer active learning, adult learning, and open pedagogy strategies and how these might be implemented in an OER.

Learner to Learner

Active learning strategies support engagement of learners (Freeman et al., 2014). When constructed thoughtfully, engaging in shared learning with peers can build community, leading to feelings of belonging and feeling connectedness (Martin & Bolliger, 2018). Consider supporting learner-to-learner active learning with

- Collaborative group work using Hypothes.is

- Case study discussions using Hypothes.is

Take engagement between learners up a notch by applying open pedagogy. Learners who are included in the process of creating content or interactive learning objects for an OER tend to be more motivated learners (Clinton-Lisell & Gwozdz, 2023). Consider supporting learner-to-learner open pedagogy with

- Student-created presentations, videos, or audio using H5P Course Presentation, H5P Interactive Video, or H5P Audio

- Student-created infographics using Canva or H5P Column tool

- Student-created images using one of several H5P image tools

- Student-authored sections or chapters of your OER

Learner to Instructor

The learner-to-instructor interactions can greatly impact a learner’s level of engagement, but it can also affect learning outcomes (Dixson, 2010; Gayton & McEwen, 2007). Knowles’s (2013) Adult Learning Theory posits that adult learners require different methods to engage in learning; they engage when the instruction is relevant, practical, experiential, and when they can self-direct their own learning. Consider supporting learner-to-instructor adult, active learning with:

- Student reflections, notes, and takeaways from the learner using H5P Documentation tool or H5P Cornell Notes

- Student-generated outlines or guided responses to instructor prompts using H5P Documentation tool or H5P Structure Strip

Learner to Content

The learner-to-content interaction is most easily exemplified within OER. The most effective way to engage your learners with the content you are creating is to ensure it includes subject mastery by aligning your content with your learning objectives while including real-world examples (Britt, 2015) and a variety of authentic activities (Dixson, 2010; Revere and Kovach, 2011). Consider supporting learner-to-content active learning with

- Student interaction with text, images, video, and audio (See H5P for Presenting Your Content)

- Student interaction with real-world application or case studies (See H5P for Reflection and Deeper Learning)

- Student annotation with Hypothes.is

Learners can also interact with content by creating formative assessments or interactive learning objects based upon the content. When learners are involved in creating instruction, their critical thinking skills improve (Hilton III, J, 2020). Consider supporting learner-to-learner open pedagogy with:

- Student-created interactive learning objects (See H5P for Interactivity and H5P for Deeper Learning)

- Student-created formative assessments (See H5P for Formative Assessment)

Besides ensuring the tools we choose are accessible and engage our learners, we have one more thing to consider: the sustainability of our tools.

Resources

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2008). Learning by viewing versus learning by doing: Evidence‐based guidelines for principled learning environments. Performance Improvement, 47(9), 5-13. DOI: 10.1002/pfi.20028

Clinton-Lisell, V., & Gwozdz, L. (2023). Understanding student experiences of renewable and traditional assignments. College Teaching, 71(2), 125-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2023.2179591

Dixson, M. D. (2010). Creating effective student engagement in online courses: What do students find engaging? Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10(2), 1–13.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 111(23), 8410-8415. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Gayton, J., & McEwen, B. C. (2007). Effective online instructional and assessment strategies. American Journal of Distance Education, 21(3), 117–132. doi:10.1080/08923640701341653

Hilton III, J. (2020). Open educational resources, student efficacy, and user perceptions: A synthesis of research published between 2015 and 2018. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(3), 853-876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09700-4

Knowles, M. (2013). Andragogy: An emerging technology for adult learning. In Boundaries of adult learning (pp. 82-98). Routledge.

Martin, F. & Bolliger, D.U. (2018). Engagement matters: Student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment. Online Learning 22(1), 205-222. doi:10.24059/olj.v22i1.1092

Moore, M. J. (1993). Three types of interaction. In K. Harry, M. John, & D. Keegan (Eds.), Distance education theory (pp. 19–24). New York: Routledge. DOI:10.1080/08923648909526659

Newmann, F. M., Wehlage, G. G., & Lamborn, S. D. (1992). The significance and sources of student engagement. In F. Newmann (Ed.), Student engagement and achievement in American secondary schools (pp. 11–39). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Revere, L., & Kovach, J. V. (2011). Online technologies for engaged learning: A meaningful synthesis for educators. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 12(2), 113–124.

This is a H5P Interactive Video. This H5P type allows creators to add engaging interactivity and formative assessments to existing videos.

H5P is a free, open-source interactivity building tool built into Pressbooks. The H5P Interactive Video is one of over 50 different types of H5P interactives.

This is an H5P Quiz. This H5P type allows creators to add a set of different types of quiz questions such as multiple choice, drag and drop, or fill in the blank questions.

H5P is a free, open-source interactivity building tool built into Pressbooks. The H5P Quiz is one of over 50 different types of H5P interactives.