1 Where Does Rhetoric Come From?

Overview

Finally, it acknowledges that the standard story of rhetoric often overlooks contributions from women, non-Western cultures, and marginalized groups. Traditionally, rhetoric has been linked to power, often reinforcing social hierarchies, but it has also served as a tool for resistance and change. We encourage students to challenge and expand the rhetorical canon by incorporating global traditions and alternative histories.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Summarize the standard history of the Western rhetorical tradition, as well as its gaps and erasures

- Identify ancient controversies about the relationships among rhetoric, power, and popular governance

- Articulate how the Western rhetorical tradition has both fostered and challenged social injustices

- Give examples of non-Western rhetorical traditions, including communication practices that have been marginalized or overlooked in the Western study of rhetoric

What Is Rhetoric? The Story So Far

Rhetoric may be defined as the faculty of observing, in any given case, the available means of persuasion.

–Aristotle

Rhetoric is the art of the good man speaking well.

–Quintillian

A mode of altering reality, not by direct application of energy to objects, but by the creation of discourse which changes reality through the mediation of thought and action.

–Lloyd Bitzer

A field of study that embraces the imperative to understand truths and consequences of language more fully.

–Jacqueline Jones Royster

Rhetoric is concerned with the state of Babel after the Fall. …[Rhetoric] is rooted in an essential function of language itself, a function that is wholly realistic, and is continually born anew; the use of language as a symbolic means of inducing cooperation in beings that by nature respond to symbols.

–Kenneth Burke

…[T]he institutions, publics, and students we serve often think rhetoric is simply ‘words, words, words.’ And sometimes, we in the disciplines wanna take our two peas and pick them outta they one pod, where rhetoric be in the mind, while composition be the written manifestation of that internal work. But, hold up! What if we think of rhetoric and composition as live, as embodied actions, as behaviors, yes, as performances inside of one pod — our discipline — that lead to the creation of texts, to presentations, that invite mo performances and certainly mo co-performances?

–Vershawn Ashanti Young

As you can see, there is no single or easily agreed-upon definition of rhetoric. At various points in human history, from ancient times to the present, it has variously been connected to speech, writing, persuasion, identification, and more.

One reason for this diversity of definitions is that rhetoric evolved in different times and places to meet the needs of people in diverse historical and cultural contexts. The conventional story of rhetoric’s origins is that it was first studied and taught in ancient Greece, alongside the development of democracy in Athens. In this context, all Athenian citizens — that is, all Athenians who were men, from an Athenian family, not enslaved people, and eligible to own property — participated in the institutions of government. To participate effectively in the courts and public forums, citizens needed training in speech, especially persuasive speech. This need was met by traveling teachers called the Sophists, who taught the skills of oratory and argument.

The Sophists

The Sophists were the first professional rhetoricians, and they got their start in fifth-century BCE Sicily. According to one version of rhetoric’s rise, the Sophists rose to prominence after the overthrow of tyrannical rulers who had confiscated the property of many citizens. These citizens had to go to court to win back their property, and so the Sophists began to teach people how to argue their cases effectively. Although it’s difficult to know whether this version of events reflects the exact historical truth, this origin story highlights three key aspects of rhetoric:

- Rhetoric can only thrive when violence is contained — when people’s actions are shaped by persuasion rather than controlled by force.

- Rhetoric has always been thought of as something that can be taught and learned, not just an innate capacity.

- Rhetoric is closely tied to power — those who master persuasive language can wield significant influence.

Although much of their work survives only in fragments, the Sophists emphasized that rhetoric was a tool for persuasion rather than a tool for truth. This perspective reflected their belief in the unknowability of truth, as well as the practical utility of rhetoric to win arguments and navigate social and political challenges (Kennedy).

Review: “The Sophists” [Website] Slide Deck

Watch: “The Rise of Rhetoric in Ancient Greece” (~4 mins)

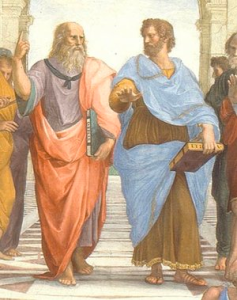

The Battle for Rhetoric: Plato vs. Aristotle

A contemporary of the Sophists, Plato (428–354 BCE) was a prominent Greek philosopher who profoundly influenced Western thought — and who was among the first to give rhetoric a bad name. A student of Socrates, Plato was highly critical of the Sophists. In his dialogues, particularly Gorgias, he critiqued rhetoric, likening it to “pastry cookery” — a skillful knack (like baking a fancy cake) that lacks systematic principles or a proper intellectual foundation (Plato).

Like the Sophists, Plato argued that rhetoric aims to persuade rather than seek truth. However, unlike the Sophists, he believed that absolute truth was possible and knowable. Plato argued that rhetoric relied on doxa, or common opinion, rather than fostering genuine knowledge or wisdom. His skepticism of rhetoric highlights a tension between persuasion and truth that remains relevant in discussions of rhetoric today.

Aristotle (384–322 BCE), Plato’s most famous student, disagreed with his mentor’s dismissal of rhetoric as merely a tool for manipulation. In The Rhetoric, written around 367–322 BCE, Aristotle defended rhetoric as both systematic and philosophical. He saw it as an essential tool for navigating uncertainty and making decisions in complex situations. While he acknowledged that rhetoric could be used unethically, Aristotle championed “ethical rhetoric” — persuasion that provides listeners with all the information needed to make an informed choice and respects their freedom to decide (Aristotle).

Aristotle also differed from Plato in his view of human nature. Whereas Plato was skeptical of people’s ability to resist manipulation, Aristotle believed humans possess a natural capacity to discern truth and make sound judgments. He further assumed that people share common values and cultural understandings, which rhetoric can appeal to constructively. Aristotle’s work was meant to defend rhetoric by positioning it as a vital and honorable practice, integral to philosophy and civic life.

Reflection

- Plato argued that people are generally ignorant (lack subject-specific knowledge) and are easily manipulable. In fact, he called them “senseless as children.” Aristotle, on the other hand, thought that people had a “sense of the truth” and would, over time, tend to be persuaded by the best argument.

- Which view of human nature do you agree with?

- Plato and Aristotle lived in one of the world’s first democracies (although participation was severely limited) and had to deal with some of the same problems that we deal with today in our own democracy.

- What does each of their views of human nature reveal about the problems and possibilities of democracy — and the uneasy relationship between democracy and persuasion?

- Aristotle believed that rhetoric was ethical when the rhetor and audience share common beliefs, because then they can actively participate in building and creating the argument together.

- What happens when rhetors and audiences come from different cultural backgrounds?

- What problems might this pose for persuasion?

- How might rhetors try to navigate or address this problem?

Roman Rhetoric and the Teaching Tradition

Over time, the study of rhetoric became an integral part of ancient Greek education, and rhetoric assumed its place as one of the seven classical liberal arts. Later Greek and Roman thinkers continued to teach rhetoric in ways that they deemed important for students of the day. The Roman rhetorician Cicero, for example, made his political career by thwarting a conspiracy in the Roman Senate. Cicero’s approach to the study of rhetoric also denounced corrupt speakers and instead described the ideal orator as one who is educated in a wide range of areas, especially ethics and philosophy. The Romans also strongly contributed to the development of rhetoric as an art that could be learned systematically. Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria (Institutes of Oratory) is a 12-volume textbook that outlines the ideal program of education for a student of rhetoric and the skills that they should master, from early childhood education in literature and language to fine-tuning how the ideal orator should stand or use their hands while speaking.

This focus on rhetoric as a form of pedagogy, or teaching — particularly for the children of the rich and powerful — survived the collapse of the Roman Empire and continued to develop through the Middle Ages and Renaissance. By the 18th and 19th centuries, following Quintillian’s example, elaborate handbooks had been developed to explain effective speaking and writing practices.

Today, when rhetoric is talked about in public discourse, it’s most commonly used as a synonym for tricky speech or spin, using language to promote a particular agenda. This view of rhetoric aligns it with the tradition of persuasive speech that dates back to Ancient Greece and the overemphasis on style rather than substance from the 19th-century tradition. But the ethical questions about how we use language and how language guides our thoughts and actions still persist.

Behind the Scenes

While the history of rhetoric that you have just read is a conventional narrative about rhetoric’s origins and development from ancient Greece to modern times, this story also leaves out a lot that is important. Some of those absences can be observed in the history itself — for example, go back to the criteria that made one eligible for citizenship in ancient Athens: a citizen had to be male, from an Athenian family, not an enslaved person, and able to own property. Women were not counted as citizens; neither were people born outside of Athens; neither were enslaved people. In other words, the list of people who could be citizens — and could study rhetoric as a result — excluded more people than it included.

Think back to the instructions for nonverbal communication that the Roman rhetoricians developed. Many of those best practices, such as eye contact with one’s audience, the use of gestures, and clear pronunciation, are still used by professional communicators today. But these ideals for public speaking assume that the speaker is able-bodied and neurotypical.

The conventional history of rhetoric also frequently fails to recognize speeches and writing from women and people of color.

Telling Other Stories

The Pre-Columbian Americas cannot be conceived as having Athenian Rhetorike, yet conceptualizing the Americas as having lowercase “alternative rhetoric” presents a colonial negation. This is the problem with the concept of Rhetorike once we move across cultural borders… If the culturally provincial concept of Rhetorike is indeed the historically unavoidable point of origin, I propose the enactment of “thinking between” multiple means of identification, between the colonizing West and te-ixtli, the “other face” of the Americas.

–Damián Baca

While much of rhetorical study in the West traces its origins to ancient Greece and Rome, many cultures across the world have rich rhetorical traditions that developed independently or in parallel with Western theories. In ancient China, Confucian and Daoist traditions engaged in debates over ethical persuasion, moral reasoning, and the power of language to shape society (Lu). The Indian tradition of Sanskrit rhetoric, as seen in texts like the Nāṭyaśāstra and the Arthaśāstra, emphasized the relationship between rhetoric, aesthetics, and governance (Das). Meanwhile, Arabic rhetorical traditions, particularly the study of balāgha, or eloquence, flourished in the medieval Islamic world, influencing theology, philosophy, and poetics (Samarrai).

Oral traditions also play a crucial role in rhetorical practices outside the Western canon. In many Indigenous cultures, such as those of West Africa and the Americas, rhetoric is deeply tied to storytelling, performance, and communal wisdom. African griots, for example, serve as historians and persuaders through oral narrative, while the Aztec and Maya civilizations used structured speech and poetic discourse for political and spiritual influence (Gleason; Carrasco). These traditions demonstrate that rhetoric is not limited to one lineage but is a global phenomenon, shaped by diverse histories, values, and communicative strategies. By acknowledging these perspectives, we gain a more comprehensive understanding of how persuasion and meaning-making function across cultures.

Rhetoric at USF

At USF, the study of rhetoric and language embraces a diversity of traditions and perspectives. We believe that students should have the resources to excel in all aspects of communication and literacy. This includes an understanding of rhetoric that spans composition, public speaking, and academic English for multilingual students. You might be reading this chapter as part of your writing or speaking requirement, or maybe a more specialized topics course that studies digital media, graphic novels, rhetoric, popular culture, or any number of other contexts where rhetoric can help us make sense of the world. Across all of these courses and throughout this textbook, our study of rhetoric is guided by a commitment to celebrating diverse voices and advancing communication for the common good (the Jesuit tradition of eloquentia perfecta [Chapter 4], which you will learn more about in later chapters).

So, as you continue to study and practice rhetoric, remember that you are participating in a long history and tradition. This tradition provides us with plenty of resources and guidance, but it has also evolved and changed over time to suit the needs of the day and the people using it. Understanding this history can be useful, but just as important is what you will do with it in the present to (in USF’s words) change the world from here.

Test Your Knowledge

Sample Assignments

Research: Exploring the Origins of Rhetoric Beyond the West

Objective: This assignment asks you to research and analyze the origins of rhetoric or rhetorical theory in a non-Western context. While much of the traditional study of rhetoric focuses on figures like Aristotle, Cicero, and Quintilian, rhetorical traditions have deep roots in many cultures worldwide. Your task is to select a historical or theoretical example from a non-Western tradition, explore its principles and practices, and consider how it compares or contrasts with classical Western rhetoric.

Instructions: Choose a non-Western rhetorical tradition. Select a historical period, theorist, or rhetorical tradition from a non-Western context. Some examples include:

- Ancient China: Confucian rhetoric, the debate traditions of Mohism and Daoism

- India: Sanskrit rhetorical theory (Nāṭyaśāstra, Arthaśāstra), Buddhist argumentation

- Mesoamerica: Aztec or Maya rhetorical traditions, the role of speech and persuasion in Nahuatl culture

- Islamic World: Classical Arabic rhetoric (balāgha), medieval Islamic discourse and persuasion

- West Africa: Griot oral traditions, proverbs, and storytelling as persuasive forms

- Japan: Rhetoric in classical Japanese court discourse, Zen rhetoric

Conduct Research: Use scholarly sources, including academic books, journal articles, and credible websites, to explore the tradition. Consider questions such as:

- What were the key rhetorical principles or methods in this tradition?

- Who were the main theorists or practitioners of rhetoric in this culture?

- How was rhetoric used in governance, law, education, or daily life?

- How does this rhetorical tradition compare to classical Western rhetoric?

Further Reading and Resources

- “Ancient Rhetoric,” in Diving Into Rhetoric

- “What Is Rhetoric? A ‘Choose-Your-Own-Adventure’ Primer”

- “Rhetoric: How to Decode Rhetorical Situations and Communicate with Power”

Works Cited

Aristotle. Rhetoric. Translated by W. Rhys Roberts. The Rhetoric and Poetics of Aristotle, Modern Library, 1954, pp. 24-31.

Baca, Damián. “te-ixtli: The ‘Other Face’ of the Americas.” Rhetorics of the Americas: 3114 BCE to 2012 CE, edited by Damián Baca and Victor Villanueva, Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, pp. 1–13.

Bitzer, Lloyd. “The Rhetorical Situation.” Philosophy & Rhetoric, vol. 1, no. 1, 1968, pp. 1–14.

Burke, Kenneth. A Rhetoric of Motives. University of California Press, 1969, p. 43.

Carrasco, Davíd. City of Sacrifice: The Aztec Empire and the Role of Violence in Civilization. Beacon Press, 2000.

Cicero. De Oratore. Translated by E.W. Sutton and H. Rackham, Harvard University Press, 1942.

“Crop of The ‘School of Athens’.” Wikimedia Commons, uploaded by Jacobolus, https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sanzio_01_Plato_Aristotle.jpg.

Das, Jishnu. Rhetoric and Aesthetics in the Indian Tradition. Routledge, 2018.

Delaune, Etienne. Rhetoric. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/399344.

Duffy, William. “What Is Rhetoric? A ‘Choose-Your-Own-Adventure’ Primer.” Writing Spaces, vol. 5, 2023, https://writingspaces.org/what-is-rhetoric-a-choose-your-own-adventure-primer/.

Gleason, Jean. “African Oral Tradition and Rhetoric: A Historical Perspective.” African Studies Review, vol. 57, no. 2, 2014, pp. 85-106.

Kennedy, George A. A New History of Classical Rhetoric. Princeton University Press, 1994.

Lu, Xing. Rhetoric in Ancient China, Fifth to Third Century B.C.E.: A Comparison with Classical Greek Rhetoric. University of South Carolina Press, 1998.

“Magnifique gateau a la creme de mirabelle.” DeviantArt, uploaded by elie2027, https://www.deviantart.com/elie2027/art/gateau-a-la-creme-de-Mirabelle-1026552366.

Meredith, Leigh. “The Sophists.” Canva, 15 July 2025, https://www.canva.com/design/DAFs2YPcMqc/mO_PBDoB3Im8JWLwDF3fbg/edit. Canva presentation.

Moxley, Joseph. “Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication.” Writing Commons, 2023, https://writingcommons.org/section/rhetoric/.

Palmer, Karen. “The Middle Ages.” Diving Into Rhetoric, Pressbooks, 2020, https://pressbooks.pub/divingintorhetoric/front-matter/introduction/.

Plato. Gorgias. Translated by W.R.M. Lamb, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 1925.

Quintilian. Institutio Oratoria. Translated by H.E. Butler, Harvard University Press, 1920, Book XII, Chapter 1.

“Ripa – Iconologie – 1643 – p. 95 – eloquence.jpg.” Wikimedia Commons, uploaded by Seudo, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ripa_-Iconologie–1643-_p.95-_eloquence.jpg.

rmilloy28. “Rise of Rhetoric in Ancient Greece.” YouTube, 23 Jan. 2012, www.youtube.com/watch?v=6egBSZN5Dkc. Accessed 13 July 2025.

Royster, Jacqueline Jones. Traces of a Stream: Literacy and Social Change among African American Women. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012.

Samarrai, Qasim. “Balāgha and Islamic Rhetoric in the Medieval Arab World.” Journal of Arabic Literature, vol. 22, no. 1, 1991, pp. 33-50.

Young, Vershawn Ashanti. “Should Writers Use They Own English?” Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 12, no. 1, 2010, pp. 110-117.

Attributions

This chapter was written and remixed by Phil Choong and Leigh Meredith.

Media Attributions

- Crop of The “School of Athens” © Uploaded by Jacobolus to Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Magnifique gateau a la creme de mirabelle © elie2027 is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Ripa – Iconologie – 1643 – p. 95 – eloquence.jpg © Uploaded by Seudo (talk | contribs) to Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Rhetoric © Etienne Delaune is licensed under a Public Domain license