6 The Hidden Language of Language

Overview

This chapter explores the concepts of language ideology and language attitudes, examining beliefs about what counts as “good communication.” We’ll explore how these ideas are shaped by group identity, highlighting the effect of shared norms and values on communication practices. We’ll also connect these ideas to systems of power and privilege. We’ll consider how certain ways of speaking or writing are privileged over others, and how these preferences can be tied to social hierarchies. By understanding these dynamics, you will learn to critically evaluate how language both reflects and reinforces power structures in society, as well as how it shapes individual and group identities.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Define “language ideology,” including how shared norms and values within specific groups shape beliefs about “good communication”

- Analyze the power dynamics of language, including how societal hierarchies influence language attitudes and privilege certain communication practices over others

- Reflect on your own language ideologies, assessing how they can reflect and reinforce systems of power and privilege, shaping your individual and group identities

The Hidden Language of Language

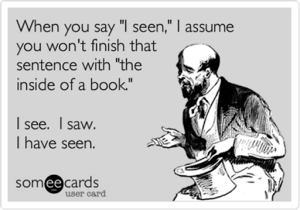

Is there a “right” way of speaking or writing?

Does the “right” way change, depending on where you are and who you’re talking to? Do you feel you have to alter your style of speaking, word choice, or sentence structure to fit different contexts or audiences? Do you feel like your audience might judge you negatively if you don’t use the “right” language to talk to them?

Most of us have had to change our communication style to fit a specific situation at some point. This could relate to switching from one language to another (say, from English to Spanish); but it could also mean a more subtle change, like a shift in tone, word choice, or formality. For example, think of switching from a “home” dialect (the way you speak to your friends and family) to a “school” dialect (the way you speak to your teachers).

In some ways, this is what rhetoric is all about — making a message that fits the situation. But we can look beyond specific message construction to uncover how our language itself — our way of speaking and writing — triggers assumptions and associations in the minds of our audience. How do these standards and assumptions come to be? What consequences and effects do they have on us as individuals and as a society?

The answer to these questions is connected to the concept of language ideologies. To define this term, linguist Benjamin P. Kantor writes, “Put simply, a language ideology may be regarded as the collection of beliefs and attitudes one has about their own language and/or the languages of others” (Kantor [Online PDF], 18).

More specifically, this “collection of beliefs and attitudes” can include ideas about a language’s:

- Origin (where the language comes from)

- Evolution (how it has changed or stayed the same)

- Value (if it’s “good” or “bad” or “better” or “worse” than another language)

- Rules and standards (like grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation)

It can also include demographic assumptions about the people who use that language, including:

- Education

- Race

- Age

- Gender

- Nationality or region of origin

- Sexual orientation

- Socioeconomic status or class

It can even lead to judgments about a communicator’s character traits, including:

- Intelligence

- Skill

- Authority

- Trustworthiness

Finally, ideas about language are strongly tied to ideas about belonging — whether or not a communicator is considered to be an insider or an outsider to a particular group. This could be an ethnic or national group (Chicano vs. Filipino), a political party (Democrat vs. Republican), an academic field (history vs. biology), a profession (lawyer vs. electrician), or even a club (sorority vs. Model UN). In this way, language ideologies intersect with discourse communities [Chapter 15] — an idea we’ll explore in future chapters.

In researching the function of language in creating national identity in Ukraine, Niklas Bernsand [Website] writes, “Since a language ideology always contains notions on the extra-linguistic qualities of the speech community it is directed towards, definitions of who belongs and who does not involve processes of language-based border making. Language forms and speakers are thus placed inside, outside, or in between the speech communities” (Language Ideology).

In other words, this is what we might call the “hidden language of language” — the way that it often implicitly communicates (or seems to communicate) so many markers of group and individual identity.

The following video illustrates some of these ideas about the relationship between language, group belonging, and perceptions of the “right” and “wrong” way to speak in different contexts. Note that the speaker uses the word “rape” in reference to her community’s loss of language — a word choice we’ll ask you to reflect on below.

Watch: Jamila Lysicott’s “3 Ways to Speak English” (~4 mins)

Reflection

- Have you ever been in a setting where you either had to or felt pressured to speak differently than you naturally would at home? How did it make you feel? How did you respond to this explicit or implicit demand for different types of language?

- Lysicott says that her original language has been “raped away.” What does that mean to you? What historical context do you think she’s referring to? Why do you think she chose such violent and attention-grabbing language? How did that language impact you as a listener?

Linguistic Discrimination

As the video above illustrates, languages don’t just mark different forms of group or collective identity, but also tend to mark ranked identities. In other words, language ideologies erect hierarchies — ideas about which languages and identities are subjectively perceived as more or less desirable. This results in linguistic discrimination.

Linguistic discrimination can take many forms. It typically involves prejudice about the vocabulary, grammar, or accent that a speaker uses. It can even involve nonverbal mannerisms — like gestures — or voice qualities — like vocal fry or upspeak.

Exploration: Listening for Linguistic Discrimination

Some of these forms of discrimination are explored in the following episodes of National Public Radio (NPR) shows like Fresh Air [Website] and To the Best of Our Knowledge [Website]. Choose one or more of the following episodes to investigate each topic further:

- “Can You Sound Gay?” [Website] (~37 mins)

David Thorpe is a filmmaker who went in search of his voice. For his documentary “Do I Sound Gay?” he investigated why he and many other gay men ended up with a “gay voice” — one with precise enunciation and sibilant “s” sounds.

Before and since Keith Powell’s breakthrough role as Toofer on the sitcom 30 Rock, he has confronted Hollywood’s tendency to stereotype Black male voices.

Veronica Rueckert is a public radio producer and host, as well as a vocal coach. In this video, she explains the ways women are silenced and offers advice for women who want to tap into the power of their voice.

As the stories above illustrate, linguistic discrimination can have serious real-world impacts. Often, the impacts are professional, with bias influencing who gets hired for a job, who lands a big promotion, or who is selected for a leadership opportunity. There can be wider economic impacts as well; for example, a Stanford study [Website] revealed that landlords in the Bay Area are less likely to rent apartments to callers with an accent (Baugh), a phenomenon dramatized in this Public Service Announcement [Website] (“Accents”).

Perhaps more subtly, linguistic discrimination can impact group and individual identity. In her essay, “How to Tame a Wild Tongue” [Website], Gloria Anzaldúa writes of speaking a language — Chicano Spanish — that is seen as lesser by some English and Spanish speakers:

So, if you want to really hurt me, talk badly about my language. Ethnic identity is twin skin to linguistic identity — I am my language. Until I can take pride in my language, I cannot take pride in myself. Until I can accept as legitimate Chicano Texas Spanish, Tex-Mex, and all the other languages I speak, I cannot accept the legitimacy of myself. Until I am free to write bilingually and to switch codes without having always to translate, while I still have to speak English or Spanish when I would rather speak Spanglish, and as long as I have to accommodate the English speakers rather than having them accommodate me, my tongue will be illegitimate. (40)

Anzaldua writes of her experience of linguistic discrimination in many places — at home, on the streets, and, perhaps most importantly, at school. This raises a critical question: how can schooling reflect and reproduce problematic language ideologies and linguistic discrimination? As Anzaldua’s experience reflects, one way might be enforcing “English-only” policies, rather than offering bilingual or multilingual education options. But we can also identify other ways in which schools reproduce ideas of “correct” speaking and writing, most often through emphasis not just on English, but on “Standard English.”

Reflection

In what ways is your language connected to your sense of self, both as an individual and as a part of a larger community? Do you associate your language with your race or nationality? What other forms of communal belonging shape your language, and how does your language shape your sense of communal belonging?

Standard English

Standard English has its roots in standard language ideology — the belief that a particular form of language usage is better than others. April Baker Bell [YouTube Video], a language, literacy, and English education scholar at Michigan State University, has argued that Standard English mimics the language usage of white, male, upper-middle-class speakers, reinforcing their power over others (Baker-Bell, 100).

She writes, “The belief that there is a homogenous, standard, one-size-fits-all language is a myth that normalizes white ways of speaking English and is used to justify linguistic discrimination on the basis of race” (Baker-Bell, 99). In other words, she and others point out that it’s not a coincidence that Standard English replicates the way that people in power communicate, and that it serves to reinforce and reproduce exactly that power structure — keeping those who speak this language most fluently at the top.

For a deeper dive into linguistic discrimination as a form of anti-Black racism, including the history and development of Standard English as the “correct” way of speaking, check out the video below.

Watch: “Linguistic Discrimination and the Pitfall of Intelligence” (~20 mins)

Education and Linguistic Justice

Many scholars who study language ideology are critical of the ways that schooling in the United States reinforces Standard English, demanding uniformity that, regardless of intention, devalues cultural differences among speakers and writers while reinforcing racial and linguistic hierarchies. In contrast, Baker-Bell defines linguistic justice as “an antiracist approach to language and literacy education”(7).

Linguistic justice seeks the equity and inclusion of different linguistic identities and cultural backgrounds. Notably, linguistic justice seeks to dismantle the assumption that white, mainstream English is the only respectable way of communicating. Embodying this approach, the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC), which is the largest professional organization for researching and teaching composition, released a statement entitled, “Students’ Right to Their Own Language” [Website] in 1974. This document highlights the importance of allowing students the right to their own language:

We affirm the students’ right to their own patterns and varieties of language — the dialects of their nurture or whatever dialects in which they find their own identity and style. Language scholars long ago denied that the myth of a standard American dialect has any validity. The claim that any one dialect is unacceptable amounts to an attempt of one social group to exert its dominance over another. Such a claim leads to false advice for speakers and writers, and immoral advice for humans. A nation proud of its diverse heritage and its cultural and racial variety will preserve its heritage of dialects. We affirm strongly that teachers must have the experiences and training that will enable them to respect diversity and uphold the right of students to their own language. (4)

This raises the question of what forms of teaching and learning might best serve the cause of linguistic justice and social justice more broadly. In contrast to Baker-Bell’s approach, literary theorist Stanley Fish has argued in the New York Times that students are better equipped to confront racism and avoid linguistic bias when they have mastered Standard English, so schools should continue to teach it.

Debate: What Should Colleges Teach?

Compare and contrast Stanley Fish’s perspective with that of rhetorician Vershawn Ashanti Young, who wrote a response directly challenging Fish’s argument.

- Stanley Fish, “What Should Colleges Teach? [Website]”

- Vershawn Ashanti Young, “Should Writers Use They Own English? [Website]“

After reading both arguments, consider who you found most persuasive, and what you think should be done. What forms of language should schools teach? What forms of writing and speaking should be taught at USF? In this class?

We hope this chapter leaves you with a broader sense of the complexity of language and its social power. Composition professor Kristen Bailey and her co-authors write:

Authority is inextricably connected to language because people are inextricably connected to language. In other words, language is political because politics is all about how humans living in groups make decisions. They make those decisions by using language, and in many settings, they make decisions about language: what is and isn’t valued, appropriate, correct, and so on. The issue, of course, is who is making those decisions — or historically has made those decisions — and whose values are accounted for in the decisions that they make, in the standards that they set. (Bailey et al., 67)

As these scholars point out, the implications of language might be subtle, but they matter — these issues affect our schools, workplaces, and social settings. Recognizing and confronting these biases in ourselves and the systems we engage with is essential if we want to create a freer and fairer society for people of all linguistic backgrounds.

Reflection: What Now?

- How can ideas about “right” and “wrong” ways of communicating lead to linguistic discrimination? How can we rethink language education to address this problem?

- Do you use multiple languages or forms of speaking? What are some instances where you use slang? Do you also use slang or other languages in your speech or writing? If so, how do you feel they enrich your communication?

Test Your Knowledge

Further Reading and Resources

- “Sounds About White: Critiquing the NCA Standards for Public Speaking Competency” [Website]

- “What Color Is My Voice? Academic Writing and the Myth of Standard English” [PDF]

- “Contesting Standardized English” [Website]

- “Clarifying the Multiple Dimensions of Monolingualism: Keeping Our Sights on Language Politics” [Website]

- “Writing toward Racial Literacy” [Website]

- Bad Ideas About Writing [PDF] — Specific chapters we recommend include:

- “America is facing a Literacy Crisis” by Jacob Babb

- “Writing Knowledge Transfers Easily” by Ellen C. Carillo

- “There is One Correct Way of Writing and Speaking” by Anjali Pattanayak

- “African American Language is not Good English” by Jennifer M. Cunningham

- Often paired with Rusty Barrett’s “Rewarding Language”

- “Grading has Always Made Writing Better” by Mitchell R James

- “Undoing Appropriateness: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and Language Diversity in Education” [YouTube]

- “Embracing Multilingualism and Eradicating Linguistic Bias” [Website]

Resources for Instructors

- “Language Attitudes Discussion Board Assignments.” [PDF]

- “Resources on Antiracist and Decolonial Pedagogy for the Writing Classroom.” [PDF]

- Pedagogue Podcast [Website] — Specific episodes we recommend include:

- “Episode 7: Lisa King” [PDF] — In this episode, Lisa King talks about featuring Native American and Indigenous rhetorics and how this approach to teaching changes the writing classroom. She also shares additional resources for teachers and allies.

- “Episode 9: Beverly J. Moss” [PDF] — In this episode, Beverly J. Moss talks about her research in African American churches and communities, how she embraces community literacies in teaching, and what it means to teach writing as an African American woman in a predominantly white space.

- “Episode 20: Vershawn Ashanti Young” [PDF] — In this episode, Vershawn Ashanti Young talks about pedagogical experimentation and writing as performance, developing cultural and societal justice in the writing classroom, emphasizing self-reflection and ethical good through teaching, and understanding cultural identity and code-meshing.

- “Attitudes to Languages and Gender.” [Website]

- Engaging the Politics of Language Difference in the Writing Classroom [Website]

Works Cited

“Accents (Fair Housing PSA).” YouTube, uploaded by The Leadership Conference on Civil & Human Rights, 3 Mar. 2008, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=84k2iM30vbY.

“Attitudes to Languages and Gender.” OpenLearn Create, The Open University, https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/mod/book/tool/print/index.php?id=218952&chapterid=33178. Accessed 14 July 2025.

Baker-Bell, April. Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy. Routledge, 2020.

Ball, Cheryl E., and Drew M. Loewe, editors. Bad Ideas About Writing. West Virginia University Libraries, 2017, https://textbooks.lib.wvu.edu/badideas/badideasaboutwriting-book.pdf. Accessed 14 July 2025.

Baugh, John. “Using Linguistics to Fight Housing Discrimination.” Stanford Magazine, Jan./Feb. 2003, Stanford University, https://stanfordmag.org/contents/using-linguistics-to-fight-housing-discrimination.

Conference on College Composition and Communication. Students’ Right to Their Own Language. College Composition and Communication, vol. 25, no. 3, 1974, National Council of Teachers of English, https://cdn.ncte.org/nctefiles/groups/cccc/newsrtol.pdf. Accessed 8 Jan. 2025.

DeMint Bailey, Kristin, An Ha, and Anthony J. Outlar. “What Color Is My Voice? Academic Writing and the Myth of Standard English.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 5, edited by David Blakesley, Parlor Press, 2023, pp. 63–82.

Fish, Stanley. “What Should Colleges Teach?” Opinionator: Exclusive Online Commentary from The Times, The New York Times, 24 Aug. 2009.

Grayson, Mara Lee. “Writing toward Racial Literacy.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 4, edited by Dana Driscoll et al., Parlor Press, 2021, pp. 127–42, https://parlormultimedia.com/writingspaces/past-volumes/writing-toward-racial-literacy/.

Gross, Terry, host. “Fresh Air for July 7, 2015.” Fresh Air, National Public Radio, 7 July 2015, www.npr.org/programs/fresh-air/2015/07/07/420629510/fresh-air-for-july-7-2015. Accessed 14 July 2025.

“Hollywood’s ‘Urban’ Voice Problem.” The Voice, an episode of To the Best of Our Knowledge, National Public Radio, 22 Nov. 2015.

Howell, Nicole Gonzales. “Language Attitudes Discussion Board Assignments.” Google Docs, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1bAKoQMeBTOngjcCPFYoh9BUZAJ17BEjoULh4vJ-4IEM/edit?tab=t.0#heading=h.4x7wb6hlqfu2. Accessed 14 July 2025.

Kantor, Benjamin Paul. The Standard Language Ideology of the Hebrew and Arabic Grammarians of the ʿAbbasid Period. Open Book Publishers, 2023.

Key, Adam. “Sounds About White: Critiquing the NCA Standards for Public Speaking Competency.” Journal of Communication Pedagogy, vol. 6, 2022, pp. 128–41, https://doi.org/10.31446/JCP.2022.1.11.

“Language Ideology.” Reclaiming the Language, 24 Aug. 2016, https://reclaimingthelanguage.blog/2016/08/24/language-ideology/.

Leung, Karen. “Embracing Multilingualism and Eradicating Linguistic Bias.” TEDxYouth@Bellingham, 7 July 2018, https://www.ted.com/talks/karen_leung_embracing_multilingualism_and_eradicating_linguistic_bias.

“Linguistic Discrimination and the Pitfall of Intelligence.” YouTube, uploaded by Shanspeare, 22 May 2021, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u6vVB552ozM. Accessed 10 June 2025.

Lyiscott, Jamila. “3 Ways to Speak English.” TED, 19 June 2014, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k9fmJ5xQ_mc.

Mena, Mike. “Undoing Appropriateness: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and Language Diversity in Education.” YouTube, uploaded by Dr. Mike Mena, 13 Feb. 2019, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m92ar93EgaA. Accessed 10 Jan. 2025.

Strainchamps, Anne, host. “How Women’s Voices Get Silenced (And How You Can Learn to Speak Up).” To the Best of Our Knowledge, featuring Veronica Rueckert, Wisconsin Public Radio/PRX, 27 July 2019, ttbook.org.

Watson, Missy. “Contesting Standardized English.” Academe, vol. 104, no. 1, 2018, https://www.aaup.org/academe/issues/104-1/contesting-standardized-english.

Watson, Missy. Engaging the Politics of Language Difference in the Writing Classroom, Routledge, 2021.

Watson, Missy. “Resources on Antiracist and Decolonial Pedagogy for the Writing Classroom.” Google Docs, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1YfUJE1B6FpZhzm0aNeCpxe8hGnt8xU5Pu49Bf4wyspw/edit. Accessed 14 July 2025.

Watson, Missy, and Rachael Shapiro. “Clarifying the Multiple Dimensions of Monolingualism: Keeping Our Sights on Language Politics.” Composition Forum, vol. 38, Spring 2018, https://www.compositionforum.com/issue/38/monolingualism.php.

Wood, Shane, host. Pedagogue Podcast. Pedagogue Podcast, https://www.pedagoguepodcast.com/episodes.html. Accessed 14 July 2025.

Young, Vershawn A. “Should Writers Use They Own English?” Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 12, 2010, pp. 110-117, https://doi.org/10.17077/2168-569X.1095.

Attribution

This chapter was written by Leigh Meredith and Melisa Garcia.

Media Attributions

- Standard English © Posted by Ho'omana Nathan Horton is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license