12 What Is Genre?

Overview

This chapter introduces the concept of “genre,” defining it not only as a repeated set of stylistic features, but also as a form of “social action.” By this, we mean that genres both reflect and shape the assumptions and attitudes of their users. This chapter emphasizes the significance of genre for both specific discourse communities and the general public, where various forms — such as music, movies, and books — reflect cultural values and societal norms. We begin to illustrate how genres not only serve to organize content, but also shape audience expectations and interactions.

Understanding genre helps us to understand how people have tried to solve communication problems in the past, and to question whether these strategies are effective — and equitable — in the present.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Define the rhetorical concept of “genre”

- List examples of genres in various forms of public discourse, such as music, movies, and books

- Explain the role of genre in reflecting and shaping social norms and values

What is “genre”? Even if you don’t hear the word “genre” that often in everyday life, you may have a general sense that genres refer to categories of cultural objects, like movies, music, or books — which is exactly right! The word “genre” comes from a French word that literally means “a kind, sort, or style” (Online Etymology Dictionary [Website]). Many of us even discuss the concept of “genre” — and what we expect of specific genres — when we talk about what was surprising or clichéd about the latest Netflix horror movie, hit hip-hop song, or best-selling science-fiction novel.

Definition: Rhetorician Carolyn Miller defined genre as “a typified response to a recurring rhetorical situation” (Miller 159). This suggests that genres are sets of strategies for addressing a communication need (or “exigence”) that keeps coming up. In other words, genres are like solutions to repeating problems.

Take, for example, the films Wonder Woman [Website] and Black Panther [Website], released in 2017 and 2018. Both fall into the “superhero” genre, sharing similarities in character attributes and roles (villains and heroes), plot structures (hero defeats villain), and style (shiny outfits and lots of explosions). But what got people talking about Black Panther and Wonder Woman had as much or more to do with how they deviated from the typical expectations of superhero films as with how they conformed. In fact, it was exactly in challenging some of the genre’s typical features (like that the central superhero “must” be white and male) that these films made those typical features more obvious — and more obviously problematic.

Examples: Digging into the Superhero Genre

Interested in the origins and features of the superhero genre? Check out the Wikipedia entry on “Superhero Fiction” [Website].

This brief example may start to show why genre is a useful concept for composing and analyzing rhetoric. First, because it helps us to connect the dots — to pay attention to how all the components of a text (style and content) work together to make a message. Rhetorical scholars Karlyn Kohrs Campbell and Kathleen Hall Jamieson define genre as a “constellation of elements.”

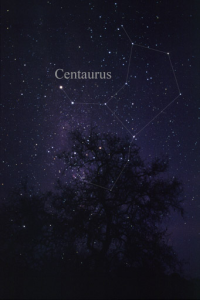

If you’ve ever spent time stargazing, you know that singling out any one star in a constellation can mean losing a sense of the constellation as a whole — it means you can’t see the Great Bear or the Little Dipper or Draco. Campbell and Jamieson suggest that we look at texts the same way. While we want to identify all the individual elements of style and substance (the costumes, colors, and character arcs), we also want to step back to see how they operate in concert.

Secondly, genre helps us to think bigger, viewing texts not as isolated or singular, but as part of larger units. Individual works, like Black Panther, are always in conversation with other, prior texts. The directors, writers, actors, and audience of Black Panther are all likely to have some familiarity with superhero films (and the comic books they come from) as a genre — and so are consciously thinking about the extent to which Black Panther shares that “superhero” DNA. The rhetorical choices of the creators — and the interpretive choices of the audience — are made in reference to the “template” of the genre (the most typical version), as well as other specific films in that genre (e.g., Iron Man or Captain America).

Thirdly, genre makes us think about the background — it makes us connect texts — and categories of texts — with the contexts they are responding to and helping to shape. This is a way of thinking about “The Rhetorical Situation” [Chapter 2] not only of individual texts, but also of entire groups of texts. What formed the superhero genre in the first place, and why did it make the leap from printed comics to films? Why did it catch on with a broad American and global audience in the last few decades? What social, economic, and political factors made the superhero genre feel relevant or reassuring? What led to the backlash against the mainstream features of the genre and the creation of Black and female protagonists?

Finally, the concept of genre helps us figure out how rhetorics are connected to ideologies [Website] — systems of ideas and beliefs. It can help us understand how the collection of characteristics that define a genre shape the kinds of messages that get made, how audiences interpret those messages, and how a text or category of text might ultimately have productive or problematic effects in the world.

Activity: The Shining — Horror Flick or Family Film?

Watch these two film trailers of the director Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 horror film The Shining.

First, watch the original trailer (~2 mins):

Next, watch the second trailer, which attempts to reframe The Shining as a heart-warming family drama (~1 min):

After watching, reflect on the following questions:

- What stylistic and editing differences do you notice between the two trailers?

- What impacts do these differences have in terms of your impression of what the film is about and what impact it’s intended to have on the audience?

- How do these differences and their impacts on audience attitudes and orientations link to our expectations for film genres? What does this tell us about the connection between generic style and substance?

- What might be the implications of this “recut” and the fact that a work can be so dramatically changed through altering its generic “markers”?

Now, we’ll shift our focus from superhero films to non-fiction genres. These are often designed to address specific rhetorical situations in public and academic spheres. While you read, consider the specific genres of your discourse community [Chapter 11] or field of study (e.g., conference presentations, journal articles, research posters, or medical logs).

Maybe this sounds a lot less interesting and fun than thinking about superhero movies. You’re not necessarily wrong. In fact, these kinds of texts are very similar to what information studies scholar Susan Leigh Star has called “boring things”; she lumps them in with phone books, manuals, and memos. But Star argues that it’s because of their very boringness — the fact that they are so mundane, dry, or difficult to understand — that they are so powerful. Star studies “infrastructures” — the hidden systems that encode values and distribute power. She points out that these infrastructures, like staircases, can be incorrectly assumed to be easy for all people to use, overlooking individuals with different needs (e.g., wheelchair users).

The genres we will study are like staircases in the example above — part of the infrastructure of public life, professional work, and the academy. Like staircases, academic genres can help some move forward (in school, in their careers, or in sharing their research) — while leaving others behind. So, in addition to thinking about how to decode and master genres, we’ll also consider how we can make them more inclusive, equitable, and accessible.

Activity: Radio Dial — Exploring Your Favorite Music Genre

Reflect on the definition of genre by connecting the concept to something you’re familiar with — like one of your favorite types of music.

Think of the music you listen to (country, hip-hop, techno, reggae, etc.) and write about its rhetorical situation [Chapter 2]. Consider the following questions:

- What topics or themes are common in the type of music you chose?

- Who is the typical audience for the genre? Why do those people like to listen to this genre (as opposed to others)?

- What’s the typical style or tone of the songs in the genre? Do any songs break these conventions?

- What kind of persona do most singers or musical artists take on in the genre?

- What social contexts are there for the music (e.g., cultural, economic, or political contexts)?

- How has the genre of the music you chose changed over time?

Further Reading and Resources

- “GENRE in the WILD: Understanding Genre Within Rhetorical (Eco)Systems”

- “Navigating Genres”

- “Rhetoric & Genre: You’ve Got This! (Even If You Don’t Think You Do…)”

- “Understanding Discourse Communities” (useful for learning more about the interaction between discourse communities and genre)

Works Cited

“Black Panther (Film).” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, last modified 14 July 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Panther_(film).

Campbell, Karlyn Kohrs. Form and Genre in Rhetorical Criticism: An Introduction. ERIC, 1978, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED151893.pdf.

“Genre.” Online Etymology Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/word/genre#etymonline_v_6006. Accessed 30 June 2025

Jamieson, K. H., and Stromer-Galley, J. (2001). “Hybrid Genres” in T. O. Sloane, (ed.), Encyclopedia of Rhetoric (pp. 361-363). New York, Oxford University Press.

https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1735&context=asc_papers#:~:text=Karlyn%20Kohrs%20Campbell%20and%20Kathleen,situation%20and%20purposes%20of%20rhetoric.

Miller, Carolyn R. “Genre as Social Action.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 70, no. 2, 1984, pp. 151–67.

“The Shining Recut.” YouTube, uploaded by SlidePlayer, 2015, https://youtu.be/KmkVWuP_sO0.

“The Shining Trailer.” YouTube, uploaded by Andrew Henderson, 2009, https://youtu.be/5Cb3ik6zP2I.

Star, Susan Leigh. ‘The Ethnography of Infrastructure’, American Behavioral Scientist, 43.3 (1999), 377–91.

“Superhero Fiction.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, last modified 15 July 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superhero_fiction.

“Wonder Woman (2017 Film).” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, last modified 15 July 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wonder_Woman_(2017_film).

Attributions

This chapter was written by Leigh Meredith.

Media Attributions

- pexels-kpaukshtite-701771 © Kristina Paukshtite

- Constellation © Till Credner via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- pexels-pixabay-434645 © Pexels is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license