15 Genre Translation

Overview

This chapter explores the practice of “genre translation,” which adapts communication from one genre to another to reach a new audience or serve a different purpose. It examines the risks and benefits of translating genres — such as the potential to broaden access to information or, conversely, to oversimplify or misrepresent complex ideas.

You’ll learn how to evaluate context-specific factors when selecting an appropriate “public genre” for a communication goal, such as audience expectations, purpose, and medium. You’ll also review examples of successful genre translations that illustrate how genre conventions can be adapted, negotiated, or challenged to fit different situations. Finally, you’ll be taught how to design your own genre translation strategies.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Explain the ethical and practical risks and benefits associated with genre translation in communication practices

- Interpret the factors involved in choosing a suitable “public genre” for a specific communication task

- Analyze professional examples of genre translation to understand how genre conventions are adapted and negotiated in different contexts

- Design a genre translation strategy for a specific communication task or professional context, considering potential risks and benefits

After reviewing the other chapters in this module, you should have a sense of the ways that discourse communities and genres shape not just the way we talk to each other, but also the ways we think and act. This means, as rhetorician and genre scholar Charles Bazerman puts it, understanding genres as “forms of life.” Bazerman writes:

Genres are not just forms. Genres are forms of life, ways of being. They are frames for social action. They are locations within which meaning is constructed. Genres shape the thoughts we form and the communications by which we interact. Genres are the familiar places we go to create intelligible communicative action with each other and the guideposts we use to explore the unfamiliar. (19)

In this chapter, we’ll continue our exploration of genres as “forms of life.” More specifically, we’ll transition to thinking about public genres — and how we can “translate” knowledge that is specific to particular disciplines and discourse communities into messages that are engaging and accessible to the general public.

Why “Translate”?

We focus on two main reasons for learning to “translate” information from one genre to another, and give particular emphasis to the importance of translating from academic to public discourse. The first involves your understanding as a learner. In his critique of teaching only “academic discourse” in college, composition scholar Peter Elbow argues that writing “like an academic” can sometimes get in the way of understanding and internalizing information:

The use of academic discourse often masks a lack of genuine understanding. When students write about something only in the language of the textbook or the discipline, they often distance or insulate themselves from experiencing or really internalizing the concepts they are allegedly learning. Often the best test of whether a student understands something is if she can translate it out of the discourse of the textbook and the discipline into everyday, experiential, anecdotal terms. (97-98)

The second main reason to practice genre translation relates to audience understanding. As discussed in previous chapters, while the communication norms of specific discourse communities can make communication within those groups more streamlined and precise, they can also create barriers to understanding for those outside the discourse community. This insider vs. outsider problem means that the norms of academic discourse can prevent the knowledge developed in specialized fields from being understood or put to use by the broader public. For example, the norms that help biologists talk to each other can be the same ones that prevent the general public from “getting” what it is that biologists are doing or learning. These communication barriers, then, can lead to all sorts of problems. They can get in the way of cross-disciplinary collaboration, limit the practical application of academic discoveries, and reduce public support and funding for scholarly work.

Dig Deeper: “Why I Write For the Public”

Check out Critical Race scholar Victor Ray’s [Website] article, “Why I Write for the Public” [Website], which explains what motivates his public writing and why he thinks all academics have the responsibility to communicate outside their specialized disciplines. He writes:

This may sound hyperbolic, but lately it feels as if we are approaching the end of the world. We are in the middle of a mass extinction; many effects of global warming are locked in and irreversible; international fascism is no longer creeping; and white supremacist violence is on the rise. A well-paid set of propagandists invested in confusing the public about the causes and consequences of the issues furthers each of these problems. Academics with real expertise on such serious problems can help ground debates in empirical fact. Many national outlets want to hear what experts have to say about both the technical aspects of these problems and the potential political solutions. (Ray)

What do you make of this statement? Do you think academics have an obligation to write for the public (and does that obligation change depending on the historical circumstances)? What should the role of “expertise” be in public debate?

The Risks of Translation

Translating academic research for broader audiences comes with risks and limitations. One major concern is oversimplification, where essential complexities or nuances are stripped away in an effort to make information more digestible. For example, in the 1970s, psychologists found a correlation between children watching violent TV and showing aggressive behavior in lab observations. Instead of providing nuanced coverage, media headlines sensationalized and simplified the issue, saying that this aggressive behavior was a direct result of watching violent TV (“What journalists get wrong about social science: full responses” [Website]). This left out key possibilities — like whether naturally aggressive children were simply more drawn to violent shows. In reality, some children did show increased aggression, but the correlation alone couldn’t prove TV was the cause (Resnick).

Another issue is misinterpretation, especially when audiences lack the background knowledge to fully grasp the context. After the rollout of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, for example, people became confused and concerned that these vaccines could alter their DNA — a misunderstanding stemming from a lack of basic knowledge of molecular biology. In fact, a Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) poll [Website] found nearly 45% of adults reported hearing the claim that “mRNA vaccines can alter a person’s DNA” (Washington).

Finally, there’s the risk of sensationalization — framing findings to attract attention. Analysis of headlines [Website] suggests that strategies used in popular journalism, like “personalization” and “celebration,” can distort the actual research (Molek-Kozakowska).

We want to reiterate that translation from academic to public audiences is critical for ensuring more equity and access to knowledge and power. But it’s important to understand the balance between accessibility and accuracy when communicating complex ideas to the public. As you work through your own projects, be mindful of what is lost or gained in the translation process.

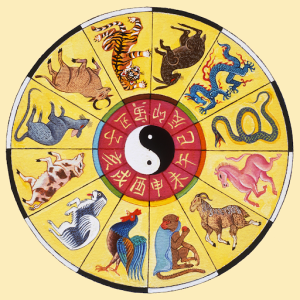

Activity: Analyzing the Translation of “Dragon Kids”

Do kids born in the Year of the Dragon (a good luck year, according to the Chinese Zodiac) really do better than kids born in other years? That’s what researchers Han Yu and Naci Mocan wanted to find out. Check out this scholarly journal article describing their research, “Can Superstition Create a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy? School Outcomes of Dragon Children of China [Online PDF]”.

Then, listen to the podcast version, “How Labels Can Affect People’s Personalities and Potential” [Website], aired on National Public Radio.

You might notice that the podcast version adds the following elements:

- Big questions: “What is it that makes you ‘you’?”

- Narratives and interviews: Data from researchers and other experts; first-hand accounts from people with personal experience

- Soundscapes: Drumbeats; sounds of school children

How do these genre elements increase accessibility and engagement? What else do you notice about what gets added or taken away? Is this an effective “translation” from academic to public discourse, in your opinion? Why or why not?

Who Is “The Public” and How Should We Communicate With Them?

Who, exactly, is “the public” and how can you effectively communicate with them? First, we want to acknowledge that “the public” [Website] is an invented concept — a way to describe and imagine a generalized audience, rather than a specialized one (i.e., a specific “discourse community”) (“Public”). Communicating effectively to the public is a critical aspect of an effective democracy, as it helps people develop informed opinions about policy. So, how we imagine the public (their knowledge, values, and experiences) has real consequences in terms of politics and power.

Ideas about who the public are, and how to talk to them, have changed over time. For example, in the U.S., in the early part of the 20th century, most “public communication” was oriented toward a college-educated audience. Since the majority of the population was not college educated, and still isn’t today (Educational attainment distribution in the United States from 1960 to 2022 [Website]), this had obvious consequences in terms of access — potentially excluding most citizens and residents (Korhonen). In the 1940s, an Associated Press writer and researcher, Rudolf Flesch [Website], argued that public communication needed to address all audiences, not just those who had been to college (“Rudolf”). He advocated for simpler sentence structure and more accessible vocabulary. This changed the way that most newspapers address the public. Alan Gould, the Executive Editor of Associated Press, wrote in 1949,

A Flesch axiom — “Write as you talk” — is now widely accepted by newspapermen… newspaper readers or radio listeners have a better chance of grasping the news, or what it means, if it is told to them simply and clearly. (Kelly)

More specifically, one of Flesch’s key guidelines for communicating with the public was to aim for an eighth-grade reading level. While the meaning of that standard has shifted over time, most readability formulas — including the metric co-created by Flesch, the Flesch-Kincaid score — evaluate it based on word and sentence length. For context, popular books like those in the Harry Potter series are typically categorized around this level (“Flesch Reading Ease”). It’s important to note that while “readability” indexes can be useful, they also have limitations, often disregarding context (like readers’ cultural backgrounds or prior knowledge) (Ozturk).

The recommendation to aim for an eighth-grade reading level has been adopted by many organizations and institutions, including the U.S. federal and state governments (“Plain Writing Act” [Website]). However, these guidelines aren’t always followed — in fact, research by Dartmouth University [Website] shows that government communication about COVID-19 failed to follow these “best practice” suggestions, and was generally closer to an 11th-grade reading level (Hirsch). While that doesn’t sound like a big deal, lead researcher Joseph Dexter argues, “The differences between eighth-grade and 11th-grade reading levels are crucial. Text written at a higher grade level can place greater demands on the reader and cause people to miss key information” (Hirsch).

While your project doesn’t need to be so focused on a precise “reading level,” you can apply general recommendations for writing in a way that’s broadly accessible. For example, the University of Toronto Writing Centre provides some of the following recommendations for writing for the public [Website] (Plotnick):

- Use common words (e.g., use “must” instead of “shall”).

- Don’t use technical terms without clearly defining them.

- Use personal pronouns like “you.”

- Use the active voice when possible.

- Use the present tense when possible.

- Avoid long strings of nouns (e.g., “The data management system implementation strategy evaluation process revealed significant inefficiencies in institutional resource allocation frameworks”).

- Avoid sentences longer than 25 words.

Dig Deeper: “How to Talk to Real People”

Check out this New York Times article, “How to Talk to Real People” [Website]. It describes a course on science communication at Emory University designed to help STEM students more clearly explain their work to public audiences. It includes a sequence of explanations of a study designed for different types of public audiences, from scholars in other academic fields to third-graders.

What do you notice about the differences in vocabulary and sentence structure used to address different audiences? How are the descriptions of research benefits or motivations different? Overall, what is gained or lost as the sequence continues?

Step 1: Planning Your Translation

If you are translating a discovery or research finding originally intended for a specialized discourse community, consider the following:

First, consider the rhetorical situation [Chapter 2]:

- Context: What background knowledge is assumed in the original book or article? What will your audience need to understand in order to grasp the importance or meaning of the research finding? How can you convey that information to your audience? Remember that there’s no way to provide all the context, so you’ll have to decide what the most important aspects are.

- Rhetor: Who are you? What special connections do you have to the subject? Why is this finding or discovery important to you? Sharing your personal connection will often help build your ethos and credibility, and can even help the audience connect to the topic and understand why it matters.

- Audience: While the section above gave general guidelines for communicating with the public, you will still need to tailor your message to fit your specific audience. Accordingly, you’ll want to consider their common experiences, values, and education level as you build your translation.

- Purpose or exigence: The reason(s) why other academics or discourse community members care about a research finding might not be compelling to the general public. Consider the following questions while you work:

- Why does the public need to know about this?

- How will it impact or improve their lives?

- How will it solve or address a problem that they have?

Step 2: Choosing Your Medium

As discussed in previous chapters, different media forms [Chapter 6] (spoken, written, or digital) will provide different costs and benefits. Consider the affordances of each media form in connection with all the aspects of the rhetorical situation. For example, TikTok might be a good choice for a younger audience, but its short-form video format might limit your ability to effectively communicate nuanced messages. Further, consider your strengths as a rhetor and communicator — which media form are you most adept at using, and which will amplify your communication strengths?

Step 3: Choosing Your Genre

Once you know what medium will work best for your audience, you can choose a specific genre. Check out the “Public Genres” [Chapter 18] chapter for more information on different genres used to communicate information to the public.

Step 4: Analyzing Your Genre

Once you’ve chosen a genre, you’ll want to understand specific features of style, substance, and situation so that you can effectively replicate them. You can follow the guidelines in the “Analyzing Genres” [Chapter 19] chapter. If you’re short on time, you can choose one or two examples from the chapter as models. These can serve as “mentor texts” to imitate (or challenge!).

Deep Dive: Podcasting — A Perfect Genre for Genre Translation

Podcasts have become an increasingly popular medium for translating information from specialized fields to the public (Drew). If you’re interested in creating podcasts, National Public Radio (NPR) has some great resources for understanding effective podcast genre features — with lots of examples to illustrate their strategies. Check out:

Step 5: Basic Strategies for Audience Engagement

The rhetorical strategies you use will depend on the genre you choose. Here are a few ideas for strategies that make information more accessible and engaging to general audiences:

- Big questions: Start with a broad, thought-provoking question that invites curiosity and shows why the topic matters for people outside of your field.

- Storytelling: Use narrative elements — like characters, conflicts, and resolutions — to turn abstract ideas into relatable, memorable experiences.

- Pathos (emotion): Tap into concepts like hope, fear, or empathy to help your audience connect with the topic on an emotional level.

- Personalization: Relate the information to your experience or that of other specific individuals or communities so readers can see how it directly affects them.

- Structure and signposts: Use clear organization, headings, and transitional phrases to guide readers through the content and prevent confusion.

- Stakes: Always explain the significance — why the audience should care and what the real-world impact or takeaway is. And remember — the takeaway for a public audience may be different from the takeaway for an academic one.

Examples: Student Podcast Translations

Listen to the following examples of “translations” of academic findings into public-facing podcasts, all created by USF students. Which do you find most (and least) compelling? Why? Which of the strategies listed above do you notice?

-

“Double Trouble: The Tale of Two Uteruses” by Meraf Sergoalem

Did you know that some women have two uteruses — and don’t even know it? It’s not science fiction; it’s a real medical condition called uterus didelphys. Imagine having two reproductive systems, yet struggling to get pregnant or carry a baby to term. Often undiagnosed due to vague symptoms, this condition affects women globally — but those in low-income countries face an even tougher road without access to early diagnosis or treatment. We’re pulling back the curtain on a reproductive health issue that’s often ignored — and exploring what that says about healthcare inequality around the world.

Text transcript of Double Trouble (Accessible Word doc [New Tab])

-

“Insect Decline” by Trent LiVolsi

In this illuminating episode, we explore the quiet crisis of insect decline — and how light pollution, especially in urban areas, plays a surprising role. Join us on a nighttime walk through San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, where we chat with experts and curious passersby under the glow of city lights. From moths that vanish before our eyes to streetlamps that never sleep, we uncover what the research says, what’s at stake, and what we can do to bring back the buzz.

Text transcript of Insect Decline and the Future of our Planet (Accessible Word doc [New Tab])

- “Cultural Literacy in the Workplace” by Samantha Fong

In this episode, we dive into the importance of cultural literacy in the business world — why it matters, what the research says, and how it can make or break relationships in today’s diverse workplaces. Your host shares a personal story about the time her dad brought her to the office as a kid — and how a colleague’s offhand, culturally insensitive comment stuck with her for years. With warmth, insight, and a touch of humor, this episode explores how everyday moments can reveal big truths about the need for empathy, awareness, and growth in professional spaces.

Text transcript of Cultural Literacy in the Worksplace (Accessible Word doc [New Tab])

-

“Critical Conversations: Family Presence During Resuscitation” by Paul Uong

This podcast examines the perspectives of family members and critical care nurses during events of cardiac arrest and resuscitation. Should families witness resuscitation efforts on their loved ones by healthcare professionals? We’ll examine the benefits and downsides of family presence during resuscitation (FPDR) and its impacts on the quality of patient care. In a conversation with an experienced, registered intensive care (ICU) nurse practitioner, we are able to take a look at first-hand experiences in meeting the challenges associated with FPDR.

Text transcript of Family Presence During Resuscitation (Accessible Word doc [New Tab])

- “Why Didn’t They Teach Me This?” by Gabe Baruzzi

This episode dives into the financial literacy crisis facing Gen Z — especially students at USF. Through student interviews, alarming statistics, and expert insights, this episode unpacks why so many young adults feel unprepared to manage money, and what can be done about it. You’ll hear real voices from USF students revealing habits and struggles, from impulse spending to confusion about topics like investing. Then, a financial expert jumps on the podcast to help break down the deeper cultural and systemic roots of the issue, including our society’s obsession with instant gratification. Finally, the episode shifts to solutions and offers practical, student-friendly advice on saving, investing early, and building better habits. This episode offers the insight and motivation many need to build a stronger financial future.

Text transcript of Why Didnt They Teach Me This (Accessible Word doc [New Tab])

Step 6: Tools for Translation — Using Generative AI

Generative AI can be a fun and useful tool to help you play around with how your content might look and sound in different genres.

For example, you might craft a prompt to ask a generative AI chatbot to “translate” a journal article into a country song — or a Shakespearean sonnet. Even if the output isn’t perfect, the quick prototypes created by AI can be a useful part of your brainstorming process. Of course, always consider the ethics of using AI and, if you use aspects of the AI-generated remix, make sure to cite your usage.

Generative AI can also help you check to see if you’ve included appropriate genre features. For example, composition professor Liza Long suggests using the following “platform-specific prompts” [Website] with a generative AI chatbot to remix your content:

Prompt: “I’ve created this blog post about [topic]: [paste blog post]. Help me repurpose this content for:

- A LinkedIn post (300 words)

- Three Twitter/X posts (280 characters each)

- An email newsletter introduction (150 words)

(Long)

Student Voices: Lessons Learned from a Podcast Translation Project

One of the assignments I had in my Rhetoric class was to make a group voice recording where each member covered the same topic, but discussed the topic through their field of study. The topic my group chose was the 2000 film, American Psycho, through the lenses of business culture, visual art, and gender studies. Our intended audience was others in our class, which led to one main issue: we were not sure who, if any, in our audience had seen the movie. We had to balance context with the time frame that we had to stick to.

In the initial draft, we followed a format where each of us talked, and then we switched to the next person. The parts that each person was in charge of could seem like segments instead of a cohesive project, which we wanted to avoid. This led us to want to change the format to something that was more interactive and connected. To fix this, we decided to take some inspiration from other podcasts, like [those published by] NPR, to make it more like a discussion. One of the difficulties with this project was making it seem smooth. We made a script to help with the flow, while making sure that we covered all of the points we wanted to make.

The next challenge was making time in my group’s schedule. We all had busy lives and conflicting schedules, but we had to make it work. We decided to work on the script asynchronously until the next week when we could record, so we would be ready and have time to practice. We recorded as soon as we could because we were using new software and equipment with no experience. By recording early, we had time to edit and re-record if needed.

I think the most effective thing about this project was how engaging it was. Due to the fact that we made our project more like a “real” podcast, in the sense of being more relaxed and intertwined with each other, it drew people in and made us stand out from the more segmented and formal work of our classmates. If we had more time, I wish that we could have gone into more detail and context for the movie to explain the importance of the movie culturally and include more scenes. This project not only made me appreciate the work that goes into making podcasts, but also highlighted what a great tool they can be for persuading people because of their easy delivery method and ease of access, along with relatively minimal skills and knowledge needed to get started.

–Lara Sipes, 2025

Lara majored in business analytics and minored in design at USF. Lara graduated in 2025.

Further Reading and Resources

- “Public Writing for Social Change” [Online PDF]

- “Four Things Social Media Can Teach You about College Writing–and One Thing It Can’t” [Online PDF]

- “Educational Podcasts: A Genre Analysis” [Website]

- “Why Remix?” [Website]

- Going Public: A Guide for Social Scientists (this is a print book, and at the moment, no free electronic access is available)

Works Cited

Amicucci, Ann N. “Four Things Social Media Can Teach You about College Writing—and One Thing It Can’t.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 4, edited by Dana Lynn Driscoll, Megan Heise, Mary K. Stewart, and Matthew Vetter, Parlor Press/WAC Clearinghouse, 2022, pp. 18–34, wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/writingspaces4/amicucci.pdf. Accessed 16 July 2025.

Baruzzi, Gabriel. “Why Didn’t They Teach Me This?” HONC 132: Rhetorical Communities, University of San Francisco, Genre Translation: Podcasts for the Public, 8 May 2025.

Bazerman, Charles. “The Life of Genre, the Life in the Classroom.” Genre and Writing: Issues, Arguments, Alternatives, edited by Wendy Bishop and Hans Ostrom, Boynton/Cook, 1997, pp. 19–26

Drew, Christopher. “Educational Podcasts: A Genre Analysis.” E‑Learning and Digital Media, vol. 14, no. 5, 30 Oct. 2017, pp. –, Sage Publications, DOI:10.1177/2042753017736177.

Elbow, Peter. “Reflections on Academic Discourse: How It Relates to Freshmen and Colleagues.” College English, vol. 53, no. 2, Feb. 1991, pp. 135-55.

“Flesch Reading Ease and the Flesch Kincaid Grade Level.” Readable, Readable.com, n.d., https://readable.com/readability/flesch-reading-ease-flesch-kincaid-grade-level/. Accessed 1 June 2025.

Fong, Samantha. “Cultural Literacy in the Workplace.” HONC 132: Rhetorical Communities, University of San Francisco, Genre Translation: Podcasts for the Public, 15 Dec. 2021.

Hirsch, David. “Federal and State Websites Flunk COVID‑19 Reading‑Level Review.” Dartmouth News, 21 Aug. 2020, home.dartmouth.edu/news/2020/08/federal-and-state-websites-flunk-covid-19-reading-level-review. Accessed 1 June 2025.

Holmes, Ashley J. “Public Writing for Social Change.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, vol. 4, edited by Dana Lynn Driscoll, Megan Heise, Mary K. Stewart, and Matthew A. Vetter, Parlor Press, 2022, pp. 199–212, writingspaces.org/wp‑content/uploads/2021/09/holmes.pdf. Accessed 16 July 2025.

“How to Talk to Real People.” The New York Times, 24 July 2011, www.nytimes.com/2011/07/24/education/edlife/edl-24jargon-t.html. Accessed 8 September 2024.

Kelly, Laura. “Why Is Newspaper Readability Important?” Readable Blog, 9 Apr. 2019, https://readable.com/blog/why-is-newspaper-readability-important/.

Korhonen, Veera, “Educational attainment in the U.S. 1960-2022,” Statista, May 30, 2025, https://www.statista.com/statistics/184260/educational-attainment-in-the-us/

LiVolsi, Trent. “Insect Decline.” HONC 132: Rhetorical Communities, University of San Francisco, Genre Translation: Podcasts for the Public, 15 Dec. 2021.

Long, Liza. “SEO Prompting with Large Language Models.” Cyborgs and Centaurs: Academic Writing in the Age of Generative Artificial Intelligence, Pressbooks Publishing, n.d., https://cwi.pressbooks.pub/longenglish102/chapter/seo-prompting-with-large-language-models/. Accessed 16 July 2025.

MacAdam, Alison. “How Audio Stories Begin.” NPR Training, 28 May 2025, www.npr.org/sections/npr-training/2025/05/28/g-s1-67588/how-audio-stories-begin. Accessed 16 July 2025.

Mocan, Naci, and Han Yu. “Can Superstition Create a Self‑Fulfilling Prophecy? School Outcomes of Dragon Children of China.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 13769, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), Oct. 2020. Journal of Human Capital, vol. 14, no. 4, 2020, pp. 485–534.

Molek-Kozakowska, Katarzyna. “Stylistic Analysis of Headlines in Science Journalism: A Case Study of New Scientist.” Public Understanding of Science, vol. 26, no. 8, Dec. 2017, pp. 894–907. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662516637321.

Ozturk, Cem Sinan and Shantanu Dutta. “Evaluating Readability Measures: Discrepancies, Limitations, and Implications.” TREOS 2025 AMCIS Proceedings, Association for Information Systems, 2025, aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1032&context=treos_amcis2025. Accessed 16 July 2025.

“Plain Writing Act of 2010.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, last edited 6 June 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plain_Writing_Act_of_2010. Accessed 16 July 2025.

Plotnick, Jerry. “Writing for the Public.” Writing Advice, University of Toronto, n.d., https://advice.writing.utoronto.ca/types-of-writing/public-writing/. Accessed 1 June 2025.

“Public.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, last edited 21 Sept. 2004, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public. Accessed 16 July 2025.

Ray, Victor. “Why I Write for the Public.” Inside Higher Ed, 16 May 2019, www.insidehighered.com/advice/2019/05/17/academics-should-write-public-political-personal-and-practical-reasons-opinion.

Resnick, Brian. “What Journalists Get Wrong About Social Science, According to 20 Scientists.” Vox, 22 Jan. 2016, www.vox.com/science-and-health/2016/1/22/10811366/psych-responses. vox.com+10vox.com+10vox.com+10

“Rudolf Flesch.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, last edited 25 May 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudolf_Flesch. Accessed 16 July 2025.

“Sentence Length.” Oxford Lifelong Learning, University of Oxford, n.d., https://lifelong-learning.ox.ac.uk/about/sentence-length/. Accessed 16 July 2025.

Sergoalem, Meraf. “Double Trouble: The Tale of Two Uteruses.” HONC 132: Rhetorical Communities, University of San Francisco, Genre Translation: Podcasts for the Public, 8 May 2025.

Smith, Robert. “Understanding Story Structure in 4 Drawings.” NPR Training, 2 Mar. 2016, https://training.npr.org/2016/03/02/understanding-story-structure-in-4-drawings/. Accessed 16 July 2025.

Stein, Arlene, and Jessie Daniels. Going Public: A Guide for Social Scientists. University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Uong, Paul. “Critical Conversations: Family Presence During Resuscitation.” HONC 132: Rhetorical Communities, University of San Francisco, Genre Translation: Podcasts for the Public, 8 May 2025.

Vedantam, Shankar. “How Labels Can Affect People’s Personalities and Potential.” Hidden Brain, 11 Dec. 2017, NPR.

Washington, Irving, Hagere Yilma, and Joel Luther. “New Vaccine Requirements, Anti-mRNA Narratives, and Disputed Gender-Affirming Care Report,” The Monitor, Vol 23, May 22, 2025. https://www.kff.org/the-monitor/new-vaccine-requirements-anti-mrna-narratives-and-disputed-gender-affirming-care-report/

“Why Remix?” Find, Customize, and Share, edited by Amber Hoye and Kelly Arispe, Boise State Pressbooks, 2023, boisestate.pressbooks.pub/pathwaysguide/chapter/why-remix/. Accessed 16 July 2025.

Attributions

This chapter was written by Leigh Meredith.

Media Attributions

- ChineseZodiac © RootOfAllLight, Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license