16 Media Matters: Oral, Print, and Digital Rhetorics

Overview

This chapter will add to our ability to analyze and produce persuasive communication by expanding our understanding of “media” — the various channels that communication can take. We’ll focus on how the impact of a message might change when it is spoken, written, or in digital form. We’ll consider how these media might be more than simply the “container for content,” but actually shape how we make and perceive messages. To quote communication scholar Marshall McLuhan, what if “the medium is the message”? We’ll also think about the relationship between technology and media, and how new technologies drive changes in the modalities and media that we use.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Identify the impact of technological advancements on communication modalities

- Articulate how various communication channels reflect and shape cultural practices and norms

- Compare and contrast the opportunities and limitations for communication offered by different media (spoken, written, or digital)

Historical Roots: The Battle Between Speech and Words

The original Greek and Roman rhetoricians focused on speech, or oration. They did this because, although the wealthy and educated men (yes, mostly men) who were trained in rhetoric were often literate, most people couldn’t read and write. That meant that, in order to persuade people, you had to talk to them.

Writing and speaking were opposed on more than just practical terms. The Greek philosopher Plato is famous for critiquing writing in his dialogue, The Phaedrus [Website]. In it, he likens writing to a drug [Website] that encourages passivity, because we can talk back to a speaker, but it’s much harder (if not impossible) to respond directly to a writer. Further, he argued that writing ultimately degrades our minds and memories. He argued that, if people began to simply write down information, their memories would get weaker and weaker — kind of like a muscle gets weaker if it isn’t exercised enough.

But, despite this critique, Plato (unlike his mentor and teacher, Socrates) actually wrote his dialogues down. This might mean that we should take his arguments against writing with a grain of salt. That being said, Plato’s critique also helps us recognize that writing itself is a technology — a tool that humans use to extend their natural capacities. In other words, while most people learn to talk without being explicitly taught, we have to go to school for years to learn to read and write.

Reflection

- Is Plato right? Do you think that the spread of writing could have impacted people’s ability to memorize information?

- What about today? In the last decade or so, we’ve “offloaded” a lot of information we used to carry around in our heads (or notebooks) to our digital devices, like our laptops and smartphones. Do you think this has impacted our memory?

Examples: Forgetting to Remember?

- How did people memorize so much in previous eras? One ancient mnemonic technique was called the “Memory Palace” [Website]. With this technique, you build a house in your mind and put important information in each “room” in the house; then, you imagine yourself walking through each room, retrieving the information as you go. It exploits humans’ natural ability to remember spaces and places better than names and dates. The famous fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes, used this method to help solve crimes. Watch “How To Remember Everything Like Sherlock” [YouTube Video]for more information, and then try it out!

- Why is it that it’s easier to remember that someone works in a bakery than it is to remember that their last name is Baker? This is called the “baker, Baker” paradox, and has to do with how we connect new information to stuff we already know (our existing “schemas”). Explore the “baker, Baker” paradox by watching this 1 minute video: “The Baker Baker Effect Explained!” [YouTube Video].

The Growth of Writing

Rhetoricians in the medieval period [Website] and Renaissance [Wesbite] became increasingly interested in writing and how the original rhetorical appeals [Website] defined by classical rhetoricians (including ethos, pathos, and logos) could be applied in writing for various purposes, like to glorify God or increase political power. In these cases, writing was a way to transcend the limits of the “here and now” and impact people far away in both space and time.

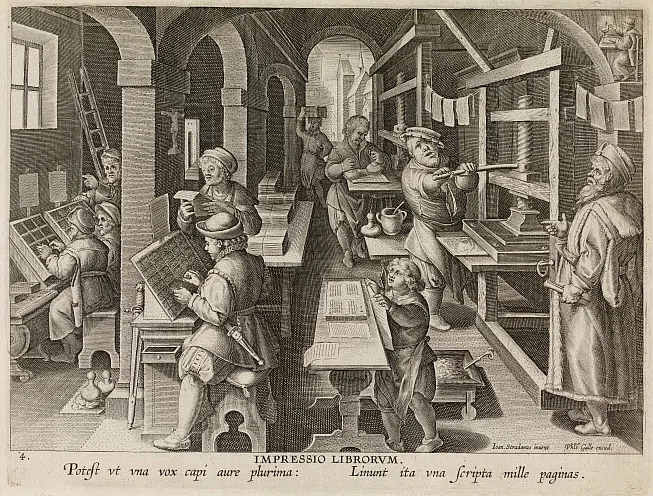

Technological revolutions also fueled the spread of writing. After the development of the printing press [Website] in the 15th century, writing became increasingly dominant. The print revolution meant that writing could be copied much faster and more precisely than copying by hand. Further, as book historian Elizabeth Eisenstein [Slide Deck] has argued, having more access to more books meant that people could more easily compare and contrast information and arguments, leading to more debates and more complex and critical thinking.

Explore

Watch The Printing Press Revolutionized the Spread of Information [Website] for more information on how the printing press revolutionized the spread of information.

Figure 16.1. Depiction of a 16th-century Flemish printing shop [Image Description]

In this way, the printing press vastly accelerated the pace at which new ideas could spread and also weakened faith in old ideas and old authorities. Some scholars have even suggested that reading (more solitary than speaking) and an increased focus on authorship as the ultimate form of creativity and self-expression intensified the growth of individualism [Website].

On the other hand, political scientist and historian Benedict Anderson has argued that the explosion in print materials, like newspapers and novels, facilitated the emergence of nationalism and national identity — because suddenly people who were separated by vast distances (say in New York City and San Francisco) could read the exact same newspaper at the exact same time — thus allowing for what Anderson called an “imagined community” [Website] of citizens. These people would never meet, but now, through shared reading, they could envision themselves sharing a common language, values, and goals. In short, the print revolution had significant impacts on identity, social structure, and ways of life.

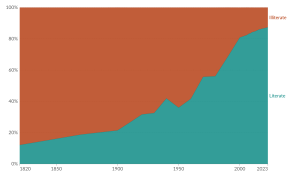

But even as writing spread, oral culture remained important, and it wasn’t until the 19th and 20th centuries that most people in even the most “industrialized” countries learned [Website] to read and write.

Figure 16.2. Literate and illiterate world population. The share of adults age 15 and older who can read and write a short, simple statement on their everyday life. [Image Description]

Even in the 19th and early 20th centuries, public speaking was a critical component of education and entertainment. In the U.S., for example, people would routinely listen to a single speaker for hours at a time — for fun! [Website] This suggests that there might be a connection not only between modality and memory, but also between modality and attention span.

Explore Further: Our Incredible Shrinking Attention Spans

Why are our attention spans shrinking? Listen to Gloria Mark, professor of informatics at the University of California, Irvine, discuss how digital devices might be impacting our ability to focus [Website].

The latest technological revolution, the digital revolution, has also reshaped how we communicate and persuade. People continue to debate the impact of the digital revolution on older modalities — for example, whether it has driven an increased focus on writing — or a return to a primarily oral and visual culture.

Digital Revolution

The digital revolution is the rapid advancement and implementation of digital technologies — most notably the computer and the internet — that began in the late 20th century. It transformed our everyday lives — and, most relevant to our focus, it impacted the way we communicate. Like the print revolution, the digital revolution reshaped the ways that people found and shared ideas, increasing the speed, distance, and ease of sharing information. In other words, the digital revolution similarly transformed how we communicate across space and time — and has had (according to some) similarly important impacts on identity, culture, and society.

Explore Further: Past or Future?

In his 2019 book, From Gutenberg to Google: The History of the Future, Tom Wheeler argues for the importance of understanding the technical and cultural similarities between the print and digital revolutions.

For example, he argues that both the print and digital revolutions not only made information spread faster and across greater distances, but also fundamentally changed the way we think about information. More specifically, he argues that one of the biggest innovations of the print and digital revolutions was the same. Both made it easier to “deconstruct” text and break it into smaller and smaller pieces, like how a press uses individual letter stamps or a computer uses code. In turn, this made it easier to reconfigure language and create new texts.

Wheeler also argues that both revolutions in technology had similar social impacts; namely, both supported democracy and self-governance because they undermined centralized control of information. In other words, in the age of hand copying, kings and the church had a lot of control over what information was reproduced and who had access to it, meaning they could largely prevent oppositional ideas from spreading. After the print revolution, it was harder to keep control over information — meaning that revolutionary ideas could be more easily spread.

Listen to an interview with Wheeler: “Don’t Panic: The Digital Revolution Isn’t as Unusual as You Think” [Website].

Reflection

- Wheeler’s arguments about deconstruction/reconstruction can also be applied to “remix” or “mashup” culture — think about the role that deconstruction (separating text, images, video, and sound from their original contexts) plays in rebuilding or remixing those messages. Are there ethical implications to this? In other words, what happens when we think of texts (or videos, or songs) not as wholes, but as bits that can be broken down and combined in new ways? What are the problems of this approach for authorship or ownership of texts? What are the benefits?

- Do you agree with the claim that the digital revolution is inherently democratic because it allows for the easy creation and spread of information and ideas? Try to think of examples that both support and contradict this claim.

And yet, just as the invention of the printing press didn’t mean that everyone could immediately read or access printed material, the invention of computers and the internet didn’t mean that everyone had equal access to digital information either. The digital divide [Website], the gap between people with access to digital information and those without, remains a problem — even as the invention of smartphones [Website] means that more people have access to internet-connected devices than ever before.

Digital Communication: Beyond Words

While earlier 20th-century technologies, like radio and television, had already begun to increase the public circulation of sounds and images, the digital revolution accelerated and intensified this trend, overcoming previous limits that made these modalities only possible in face-to-face contexts. These modalities tend to be more resource-intensive in terms of the amount of information they contain. Think of file sizes on your computer — photos and videos are often much bigger than Word documents. The old saying that “a picture is worth 1000 words” is literally true when it comes to digital information storage and transmission.

But as information sharing became cheaper and faster, more and more digital messages appeared in multiple forms — text, visual, and aural. Think of the rise of “meme culture,” combining images and text, and of video platforms like YouTube and TikTok. These new platforms often birth new genres and enable more diverse voices and formats that share features of traditional rhetorical strategies while challenging traditional forms of rhetoric.

But even as we move away from traditional modes of communication (like speaking and writing), those modes are often integrated into the new genres. Jesuit and English professor Walter J. Ong [Website], for example, argued that the digital revolution has ushered in a period of “secondary orality,” where our culture is becoming less dependent on writing, and more on speech and visual forms of communication (Ong).

Perhaps relatedly, with the growth of digital communication, public and professional writing has become more like speech in terms of tone, formality, length, and grammatical structure.

Explore Further

In their book, Remediation: Understanding New Media [Website], J. Bolter and Walter Grusin argue that new modes of communication don’t fully replace old modes, but often both assimilate and reshape them. For example, consider how email incorporates features of letter writing, or podcasting incorporates elements of radio.

Similarly, we see both the persistence and adaptation of the original rhetorical appeals [Website] like ethos or pathos; ethos can be established through online personas, while pathos is evoked (and perhaps intensified) through visual or oral storytelling.

Audience engagement has also changed, allowing for real-time interaction and feedback. Digital publication increases the ability of the audience to not just receive content, but also produce it.

Watch: “The Machine Is Us/ing Us” (~4 mins)

This video cleverly showcases the connections between form and content in digital writing, and how the shifting capacity of digital communication to allow for user contributions has changed the way we get, create, digest, and respond to information (for better and for worse).

Further, algorithms shape how content (user-generated and otherwise) is accessed, and who can most easily access it. In response to algorithmic manipulations, users have developed linguistic workarounds [Website] (like using the word “unalive” instead of “dead”) to avoid algorithmic censorship (Lorenz).

Scholars and public intellectuals continue to debate the cultural and social impacts of the shift to digital communication. Has it made us a more connected, more knowledgeable, more equitable society? Or a more divided, more manipulable, and less empowered one?

Explore Further: The Dark Side of Digital Communication

- Is digital communication bringing us together or driving us apart? Sherry Turkle addresses this question in works like Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. In her book, Turkle explores how digital media reshape interpersonal relationships and communication, making us more anxious and less able to navigate face-to-face communication. Watch her Ted Talk [Video] for an overview of her arguments.

- Just as Plato argued that writing might diminish our capacity for memory, some scholars and public intellectuals have argued that access to digital information has made us less able to evaluate and internalize information. Check out Nicolas Carr’s 2008 article, “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” [Online PDF], published in the Atlantic.

- Although the internet has increased our access to information, the algorithms used by search engines, social media (and now Generative AI chatbots) mean that not all information is equally accessible to all people. Author and technologist Eli Pariser has argued that these algorithms create “filter bubbles” and “echo chambers” that reinforce our previously held beliefs and prevent us from confronting ideas that might challenge our perspectives and prejudices. Check out his 2011 Ted Talk [Video].

Considering Affordances and Limitations

Scholars in media and communication studies use the term “affordances” to discuss the benefits and opportunities of a particular modality or media form, and “constraints” to discuss its drawbacks and limitations. Let’s apply these broadly to consider what each medium we’ve discussed in this chapter allows us to do in our quest to communicate.

Mode |

Affordances |

Constraints |

|---|---|---|

Oral |

|

|

Written |

|

|

Digital |

|

|

Test Your Knowledge

Further Reading and Resources

- “The Mid-Century Media Theorists Who Saw What Was Coming” [Podcast]

- “The Medium is the Massage” [Online PDF]

- “The Next Project Conversations Episode 4 – Adam Banks” [YouTube Video]

- “Inequity”

- “Funk, Flight, and Freedom – 2015 CCCC Chair Adam Banks’ Address” [YouTube Video]

- “Rhetorical Analysis of Digital Texts” [Website]

- “Affordances and Constraints: A Critical Analysis of Digital Spaces” [Website]

- “Where Meaning is the Issue” (Multimodality, pp. 1-17)

- “54: Texting Ruins Literary Skills” [Podcast]

Resources for Instructors

- Scaffolding a Meme-Based Assignment Sequence for Introductory Composition Classes [Website]

- Prompt for digital artifact analysis [Website]

Works Cited

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso, 1983.

Banks, Adam. “Funk, Flight, and Freedom – 2015 CCCC Chair Adam Banks’ Address.” YouTube, uploaded by National Council of Teachers of English, 24 Mar. 2015, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EYt3swrnvwU.

Baym, Nancy K. Personal Connections in the Digital Age. Polity, 2010.

Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. MIT Press, 1999.

Boyd, Danah. “Inequity.” It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens, Yale University Press, 2014.

Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. “Some Features of Print Culture.” The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press, 1983, pp. 43–69.

Justice, Christopher. “54: Texting Ruins Literary Skills.” Bad Ideas about Writing, hosted by Kyle Stedman, Spotify, 2022. https://creators.spotify.com/pod/profile/bad-ideas-about-writing/episodes/54-Texting-Ruins-Literacy-Skills–by-Christopher-Justice-e1e2t4o.

Klein, Ezra. “The Mid-Century Media Theorists Who Saw What Was Coming.” The Ezra Klein Show, The New York Times, 2022. https://open.spotify.com/episode/2RS6m8pnsyQqFiZfy1GoOr?si=b505cc7b05c44b88.

Kress, Gunther. “Where Meaning is the Issue.” Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication, Routledge, 2010, pp. 1-17.

Lorenz, Taylor. “Internet ‘algospeak’ is changing our language in real time, from ‘nip nops’ to ‘le dollar bean.’” The Washington Post, 8 Apr. 2022.

McLuhan, Marshall. The Medium is the Massage. The Internet Archive, 2014, https://archive.org/details/pdfy-vNiFct6b-L5ucJEa/page/n29/mode=2up.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. McGraw-Hill, 1964.

Miller, Cara. “Affordances and Constraints: A Critical Analysis of Digital Spaces.” Writing for Digital Media, PALNI Pressbooks, 2024, https://pressbooks.palni.org/writingfordigitalmedia/chapter/affordances-and-constraints-a-critical-analysis-of-digital-spaces/.

Ong, Walter J. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. Methuen, 1982.

Palmer, Karen. “Rhetorical Analysis of Digital Texts.” Diving into Rhetoric: A Rhetorical View of History, Communication, and Composition, Pressbooks, 2020, https://pressbooks.pub/divingintorhetoric/chapter/rhetorical-analysis-of-digital-texts/.

Pariser, Eli. “Beware Online ‘Filter Bubbles.’” YouTube, uploaded by TED‑Ed, 2 May 2011, www.youtube.com/watch?v=B8ofWFx525s.

Plato. Phaedrus. Translated by Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff, Hackett Publishing Company, 1995.

“Prompt for Digital Artifact Analysis.” Digital Rhetoric Collaborative, https://www.digitalrhetoriccollaborative.org/course_artifact/artifact-analysis-prompt-1/.

Silva, Andie. “Scaffolding a Meme-Based Assignment Sequence for Introductory Composition Classes.” The Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, 19 Dec. 2016, https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/digital-literacies-and-visual-rhetoric-scaffolding-a-meme-based-assignment-sequence-for-introductory-composition-classes/.

Smith, Kaloma. “The Next Project Conversations Episode 4 – Adam Banks.” YouTube, 24 Apr. 2020, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tka10PDRSsk.

Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. Basic Books, 2011.

Wesch, Michael. “The Machine Is Us/ing Us (Final Version).” YouTube, 8 Mar. 2007, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NLlGopyXT_g.

Wheeler, Tom. From Gutenberg to Google: The History of Our Future. Brookings Institution Press, 2019.

Image Descriptions

Figure 16.1. A detailed black-and-white engraving of a Renaissance-era printing workshop. Multiple workers in caps and tunics perform different tasks under stone arches. At left, compositors set metal type at angled cases while an apprentice carries pieces of type. In the center, men proofread pages at a tall bench and confer over copy. At right, two pressmen operate a large screw press—one inks the forme with paired ink balls while another pulls the bar—beside racks where freshly printed sheets hang to dry. Tools, pots of ink, and pages are scattered across worktables. Centered along the bottom margin is the title “IMPRESSIO LIBRORUM.” A short Latin couplet appears beneath the title: “Potest ut una vox capi aure plurima: Linunt ita una Scripta mille paginas.” The scene illustrates the coordinated labor of a 16th-century Flemish printing shop. [Return to Figure 16.1]

Figure 16.2. A stacked area chart. The vertical axis runs 0%–100%; the horizontal axis shows years 1820 to 2023. Two colors fill the chart: teal = Literate and rust = Illiterate (labels appear on the right side). The teal area slowly expands through the 1800s (from roughly one-tenth literate), rises more quickly after the mid-1900s (surpassing ~50% by the late 1960s), reaches ~80% around 2000, and about 90% by 2023; the rust area shrinks proportionally. [Return to Figure 16.2]

Attributions

This chapter was written by Leigh Meredith.

Media Attributions

- PlatoHomerSimpson © KingslayerN7

- PrintingPress © British Museum is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- literate-and-illiterate-world-population © Our World in Data is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license