Welcome to Economics!

Fixed Chapter 2

Introduction to Environmental Protection and Negative Externalities

Chapter Overview

In this chapter, you will learn about:

- The Economics of Pollution

- Command-and-Control Regulation

- Market-Oriented Environmental Tools

- The Benefits and Costs of U.S. Environmental Laws

- International Environmental Issues

- The Tradeoff Between Economic Output and Environmental Protection

Bring It Home

Keystone XL Pipeline

You might have heard about the Keystone XL Pipeline in the news. It was a pipeline system designed to bring oil from Canada to the refineries near the Gulf of Mexico, as well as to boost crude oil production in the United States. Even though a private company, TransCanada, planned to build and own the pipeline, U.S. government approval was required because of its size and location. Plans to build the pipeline included four phases, the first two of which were in operation.

Sounds like a great idea, right? A pipeline that would move much-needed crude oil to the Gulf refineries would increase oil production for manufacturing needs, reduce price pressure at the gas pump, and increase overall economic growth. Supporters argued that the pipeline would be one of the safest pipelines built yet and would reduce America’s dependence on politically vulnerable Middle Eastern oil imports.

Not so fast, said its critics. The Keystone XL Pipeline would be constructed over an enormous aquifer (one of the largest in the world) in the Midwest, and through an environmentally fragile area in Nebraska, causing great concern among environmentalists about possible destruction to the natural surroundings. They argued that leaks could taint valuable water sources and that pipeline construction could disrupt and even harm indigenous species. Environmental groups fought government approval of the proposed pipeline construction, and in November 2015, the Obama administration refused to grant the cross-border permit necessary to build the Keystone XL pipeline. In 2017, the Trump administration sought to grant the necessary cross-border permit, and legal challenges emerged. In 2021, President Biden, on his first day in office, canceled the cross-border permit, effectively ending (for now) the Keystone XL pipeline.

Environmental concerns matter when discussing issues related to economic growth. However, how much should economists factor in these issues when deciding policy? In the case of the pipeline, how do we know how much damage it would cause when we do not know how to put a value on the environment? Would the pipeline’s benefits outweigh the opportunity cost? The issue of how to balance economic progress with unintended effects on our planet is the subject of this chapter.

In 1969, the Cuyahoga River in Ohio was so polluted that it spontaneously burst into flame. Air pollution was so bad at that time that Chattanooga, Tennessee, was a city where, as an article from Sports Illustrated put it:

the death rate from tuberculosis was double that of the rest of Tennessee and triple that of the rest of the United States, a city in which the filth in the air was so bad it melted nylon stockings off women’s legs, in which executives kept supplies of clean white shirts in their offices so they could change when a shirt became too gray to be presentable, in which headlights were turned on at high noon because the sun was eclipsed by the gunk in the sky.

The problem of pollution arises for every economy in the world, whether it is high income or low income, market oriented or command oriented. Every country needs to strike a balance between production and environmental quality. This chapter begins by discussing how firms may fail to take certain social costs, such as pollution, into their planning if they do not need to pay these costs. Traditionally, policies for environmental protection have focused on governmental limits on how much of each pollutant can be emitted. Although this approach has had some success, economists have suggested a range of more flexible, market-oriented policies that reduce pollution at a lower cost. We will consider both approaches, but first, let’s see how economists frame and analyze these issues.

12.1 The Economics of Pollution

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Differentiate between positive and negative externalities.

- Identify the equilibrium price and quantity.

- Recognize how firms can contribute to market failure.

Between 1970 and 2020, the U.S. population increased by 63%, and the size of the U.S. economy increased by more than 3.8 times. Since the 1970s, however, the United States, using a variety of antipollution policies, has made genuine progress against a number of pollutants. Table 12.1 lists the change in carbon dioxide emissions by energy users (from residential to industrial) according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). The table shows that emissions of certain key air pollutants declined substantially from 2007 to 2012. They dropped 740 million metric tons a year, which is a 12% reduction. This seems to indicate that progress has been made in the United States in reducing overall carbon dioxide emissions, which contribute to the greenhouse effect.

|

Coal |

Natural gas |

Petroleum |

Total |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1973 |

1,221 |

1,175 |

2,325 |

4,721 |

|

2007 |

2,171 |

1,245 |

2,587 |

6,016 |

|

2020 |

875 |

1,648 |

2,042 |

4,576 |

Despite the gradual reduction in emissions from fossil fuels, many important environmental issues remain. Along with the still high levels of air and water pollution, other issues include hazardous waste disposal, destruction of wetlands and other wildlife habitats, and the impact on human health from pollution.

Externalities

Private markets, such as the cell phone industry, offer an efficient way to put buyers and sellers together and determine what goods they produce, how they produce them, and who gets them. The principle that voluntary exchange benefits both buyers and sellers is a fundamental building block of the economic way of thinking. However, what happens when a voluntary exchange affects a third party who is neither the buyer nor the seller?

As an example, consider a concert producer who wants to build an outdoor arena that will host country music concerts a half-mile from your neighborhood. You will be able to hear these outdoor concerts while sitting on your back porch—or perhaps even in your dining room. In this case, the sellers and buyers of concert tickets may both be quite satisfied with their voluntary exchange, but you have no voice in their market transaction. The effect of a market exchange on a third party who is outside or “external” to the exchange is called an externality. Because externalities that occur in market transactions affect other parties beyond those involved, they are sometimes called spillovers.

Externalities can be negative or positive. If you hate country music, then having it waft into your house every night would be a negative externality. If you love country music, then what amounts to a series of free concerts would be a positive externality.

Pollution as a Negative Externality

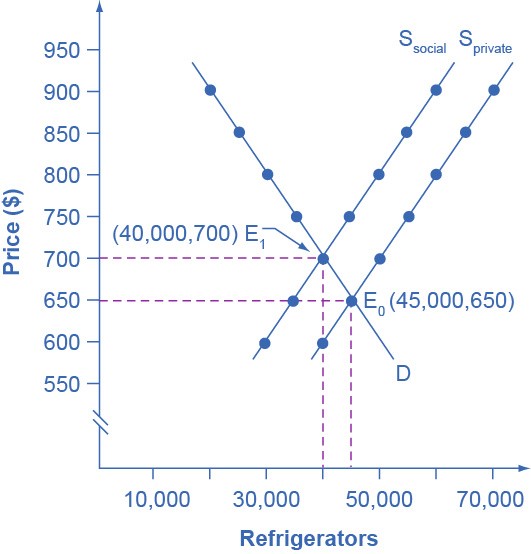

Pollution is a negative externality. Economists illustrate the social costs of production with a demand and supply diagram. The social costs include the private costs of production that a company incurs and the external costs of pollution that are passed on to society. Figure 12.2 shows the demand and supply for manufacturing refrigerators. The demand curve (D) shows the quantity demanded at each price. The supply curve (Sprivate) shows the quantity of refrigerators that all firms in the industry supply at each price, assuming they are taking only their private costs into account and they are allowed to emit pollution at zero cost. The market equilibrium (E0), where quantity supplied equals quantity demanded, is at a price of $650 per refrigerator and a quantity of 45,000 refrigerators. Table 12.2 reflects this information in the first three columns.

|

Quantity demanded |

Quantity supplied before considering pollution cost |

Quantity supplied after considering pollution cost |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

$600 |

50,000 |

40,000 |

30,000 |

|

$650 |

45,000 |

45,000 |

35,000 |

|

$700 |

40,000 |

50,000 |

40,000 |

|

$750 |

35,000 |

55,000 |

45,000 |

|

$800 |

30,000 |

60,000 |

50,000 |

|

$850 |

25,000 |

65,000 |

55,000 |

|

$900 |

20,000 |

70,000 |

60,000 |

However, as a by-product of the metals, plastics, chemicals, and energy that refrigerator manufacturers use, some pollution is created. Let’s say that, if these pollutants were emitted into the air and water, they would create costs of $100 per refrigerator produced. These costs might occur because of adverse effects on human health, property values, or wildlife habitat; reduction of recreation possibilities; or other negative impacts. In a market with no antipollution restrictions, firms can dispose of certain wastes for free. Now, imagine that firms that produce refrigerators must factor in these external costs of pollution, meaning they have to consider not only labor and material costs, but also the broader costs to society of harm to health and other costs caused by pollution. If the firm is required to pay $100 for the additional external costs of pollution each time it produces a refrigerator, production becomes more costly, and the entire supply curve shifts up by $100.

As Table 12.2 and Figure 12.2 illustrate, the firm will need to receive a price of $700 per refrigerator and produce a quantity of 40,000, and the firm’s new supply curve will be Ssocial. The new equilibrium will occur at E1. In short, taking the additional external costs of pollution into account results in a higher price, a lower quantity of production, and a lower quantity of pollution. The following Work It Out feature will walk you through an example, this time with musical accompaniment.

Check Your Learning

(Learning outcome: Differentiate between positive and negative externalities.)

Work It Out

Identifying the Equilibrium Price and Quantity

Table 12.3 shows the supply and demand conditions for a firm that will play trumpets on the streets when requested. We measure output as the number of songs played.

|

Quantity demanded |

Quantity supplied without paying the costs of the externality |

Quantity supplied after paying the costs of the externality |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

$20 |

0 |

10 |

8 |

|

$18 |

1 |

9 |

7 |

|

$15 |

2.5 |

7.5 |

5.5 |

|

$12 |

4 |

6 |

4 |

|

$10 |

5 |

5 |

3 |

|

$5 |

7.5 |

2.5 |

0.5 |

Step 1. Determine the negative externality in this situation. To do this, you must think about the situation and consider all parties that might be impacted. A negative externality might be the increase in noise pollution in the area where the firm is playing.

Step 2. Identify the initial equilibrium price and quantity, taking only private costs into account. Next, identify the new equilibrium, taking social costs as well as private costs into account. Remember that equilibrium is where the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied.

Step 3. Look down the columns to where the quantity demanded (the second column) is equal to the “quantity supplied without paying the costs of the externality” (the third column). Then refer to the first column of that row to determine the equilibrium price. When we only take private costs into account, the equilibrium price and quantity would be at a price of $10 and a quantity of five.

Step 4. Identify the equilibrium price and quantity when we take into account the additional external costs. Look down the columns of quantity demanded (the second column) and the “quantity supplied after paying the costs of the externality” (the fourth column), and then refer to the first column of that row to determine the equilibrium price. In this case, the equilibrium will be at a price of $12 and a quantity of four.

Step 5. Consider how taking the externality into account affects the equilibrium price and quantity. Do this by comparing the two equilibrium situations. If the firm is forced to pay its additional external costs, then production of trumpet songs becomes more costly, and the supply curve will shift up.

Remember that the supply curve is based on the choices about production that firms make while looking at their marginal costs, and the demand curve is based on the benefits that individuals perceive while maximizing utility. If no externalities existed, private costs would be the same as the costs to society as a whole, and private benefits would be the same as the benefits to society as a whole. Thus, if no externalities existed, the interaction of demand and supply would coordinate social costs and benefits.

However, when the externality of pollution exists, the supply curve no longer represents all social costs. Because externalities represent a case where markets no longer consider all social costs, but only some of them, economists commonly refer to externalities as an example of market failure. When there is market failure, the private market fails to achieve efficient output because either firms do not account for all costs incurred in the production of output or consumers do not account for all benefits obtained (a positive externality), or both. In the case of pollution, at the market output, the social costs of production exceed social benefits to consumers, and the market produces too much of the product.

Check Your Learning

(Learning outcome: Recognize how firms can contribute to market failure.)

We can see a general lesson here. If firms were required to pay the social costs of pollution, they would create less pollution, but they would also produce less of the product and charge a higher price. In the next module, we will explore how governments require firms to account for the social costs of pollution.

Negative Externalities of Overusing Common Goods: Tragedy of Commons

In the case of common goods, the free-rider problem leads to overutilization. This is also known as the tragedy of the commons.

The tragedy of the commons is a problem in economics that occurs when individuals neglect the well-being of society in the pursuit of personal gain.

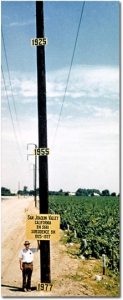

Land subsidence in California is a classic example of the tragedy of the commons. To learn more about the significant land subsidence that has occurred due to over-utilization of groundwater, thus leading to the tragedy of the commons, please read the article “Land Subsidence.” It is particularly interesting to see this historic 1977 photo of Dr. Joseph Poland, USGS, who was considered the pioneer of scientific subsidence studies (Figure 12.3). Dates on the telephone pole in the picture indicate previous land elevations in an area southwest of Mendota, which shows significant land subsidence due to over-utilization of groundwater.

Will the Ocean Ever Run Out of Fish?

One of the consequences of negative externalities is the overallocation of resources. The following video explains negative externalities and their consequences by applying them to the fish in the ocean.

Key Concepts and Summary

12.1 The Economics of Pollution

Economic production can cause environmental damage. This tradeoff arises for all countries, whether they are high-income or low-income, and whether their economies are market-oriented or command-oriented.

An externality occurs when an exchange between a buyer and seller has an impact on a third party who is not part of the exchange. An externality, which is sometimes also called a spillover, can have a negative or a positive impact on the third party. If those parties imposing a negative externality on others had to account for the broader social cost of their behavior, they would have an incentive to reduce the production of whatever is causing the negative externality. In the case of a positive externality, the third party obtains benefits from the exchange between a buyer and a seller, but they are not paying for these benefits. If this is the case, then markets would tend to underproduce output because suppliers are not aware of the additional demand from others. If the parties generating these external benefits were somehow able to receive compensation for them, they would have an incentive to increase production of whatever is causing the positive externality.