38 Algorithms: Invisibly Shaping Our Research and Ideas

Gina Kessler Lee

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to

- Explain how the biases inherent in the algorithms behind Google and other search tools might affect your perspectives and the sources you find when you search on a topic

- Identify organizations and publications that might have credible information on your topic, rather than relying on Google to point you to the sources you should use

Overview

“Everyone who has accessed the internet has experienced the personalizing actions of algorithms, whether they realize it or not. These invisible lines of code can track our interactions, trying to game our consumer habits and political leanings to determine what ads, news stories and information we see….As tracking practices have become more common and advanced, it has become urgent to understand how these computer programs work and have widespread impact. How do students understand the hidden filters that influence what they see and learn, and shape what they think and who they are?” (Head et al. 13)

We just learned about identifying appropriate keywords and subject headings to find the most relevant sources. But when you use any search engine, there’s another factor that determines what results you see first: algorithms.

Let’s say you’re being asked to take a stand on an issue. How do you find the different points of view on that issue? How do you decide what views you agree with? Your views on any given issue might be shaped by your education, by trusted people in your life, and by your own personal experiences. But how much of it is also shaped or reinforced by what you see online? That’s where algorithms come into play.

Algorithms are step-by-step instructions that computers follow to complete tasks, solve problems, and make automated decisions. They use data to make predictions about people, including their preferences, attributes, and behaviors. Algorithms power nearly everything we see online, including search engines, social media, video games, online dating, and smartphone apps. They are used to shape and filter content on the platforms many of us interact with daily, such as Google, YouTube, Instagram, Netflix, Facebook, Amazon, Twitter, and Spotify. For example, algorithms determine which websites you see first in your Google search results, which posts you see on Facebook, and which videos YouTube “recommends” and autoplays for you.

You may use Google every day, but do you really know how its search result-ranking algorithm works? Here’s a quick video [view time is 5:15] in which Google explains why some results appear at the top of your search results, while others don’t:

Video 38.1. How Google Search works by Google

Positive & Negative

“We live in an era of ambient information. Amidst the daily flood of digital news, memes, opinion, advertising, and propaganda, there is rising concern about how popular platforms, and the algorithms they increasingly employ, may influence our lives, deepen divisions in society, and foment polarization, extremism, and distrust” (Head et al. 1)

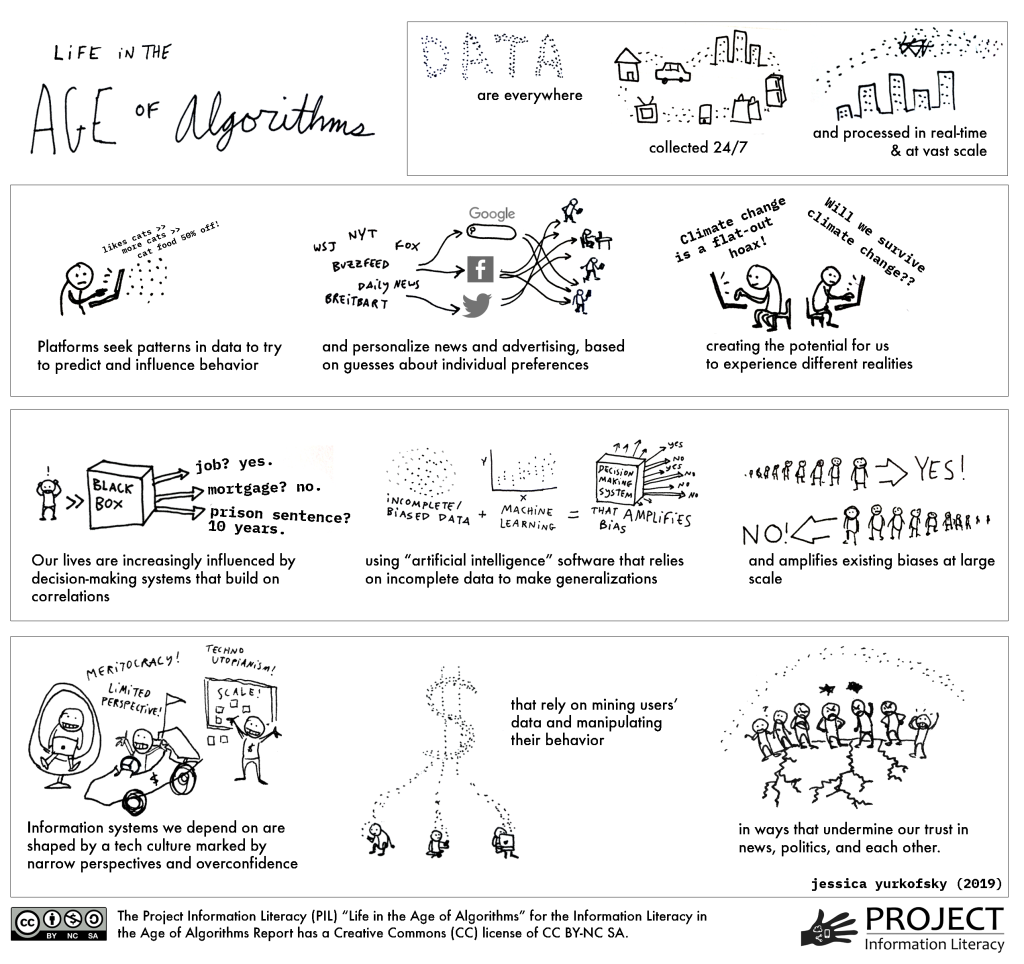

As companies, governments, and other organizations continue to collect and analyze massive amounts of our data, the use of algorithms has become pervasive. In fact, many are referring to this period as the “Age of Algorithms” or the “Algorithm Era,” and researchers are considering the significant impacts that these tools may have—both positive and negative.

There is no doubt that algorithms can be useful and help to improve our lives. For example, it certainly saves a lot of time and frustration to be able to pull up a map on our phones and instantly determine the fastest way to reach our destination. However, as technology and social media scholar danah boyd has noted, “the same technology can be used to empower people…or harm them. It all depends on who is using the information to what ends” (qtd. in Rainie and Anderson). Eni Mustafaraj, Assistant Professor of Computer Science at Wellesley College, similarly notes that “if we want more people in the world to have access to the total human knowledge accessible on the Internet, we need algorithms. However, what we need to object against are the values driving the companies that own these algorithms” (qtd. in Head et al. 42).

Concerns

What happens when algorithms are used to predict when college students are “cheating” on a test, or to predict who should be hired for a job or who should get a loan, or to decide the type of information we see in our social media newsfeeds, or to calculate credit scores, or even to predict criminal behavior and determine prison sentences? Are Google search results really an unbiased presentation of the best available information on a research question? How do algorithms impact our perception of a research topic, or of our own realities?

Zoom in [New Tab] or read the text version of the infographic [New Tab]

Freewrite

How might algorithms affect your ability to find credible, balanced, and academic information for your research assignments in college? What can you do to mitigate these effects?

Algorithmic Bias

“Although the impulse is to believe in the objectivity of the machine, we need to remember that algorithms were built by people” (Chmielinski, qtd. in Head et al. 38).

Because we often assume that algorithms are neutral and objective, they can inaccurately project greater authority than human expertise. Thus, the pervasiveness of algorithms—and their incredible potential to influence our society, politics, institutions, and behavior—has been a source of growing concern.

Algorithmic bias is one of those key concerns. This occurs when algorithms reflect the implicit values of the humans involved in their creation or use, systematically “replicating or even amplifying human biases, particularly those affecting protected groups” (Lee et al.). In search engines, for example, algorithmic bias can create search results that reflect racist, sexist, or other social biases, despite the presumed neutrality of the data. Here are just a few examples of algorithmic bias (Lee et al.):

- An algorithm used by judges to predict whether defendants should be imprisoned or released on bail was found to be biased against African-Americans.

- Amazon had to discontinue using a recruiting algorithm after discovering gender bias: The algorithm was penalizing any resume that contained the word “women’s” in the text, because the data was based on resumes historically submitted to Amazon, which were predominantly from white males.

- Princeton University researchers analyzed algorithms and found that they picked up on existing racial and gender biases: European names were perceived as more pleasant than those of African-Americans, and the words “woman” and “girl” were more likely to be associated with the arts instead of science and math.

- Numerous articles [New Tab] have examined the role that YouTube’s recommendation algorithm might play in radicalizing viewers.

Now, consider that the large language models powering generative AI chatbots like ChatGPT were trained on this data.

Challenging the Algorithms of Oppression

In the video below [view time is 20:34], digital media scholar Dr. Safiya Umoja Noble and computer scientist Dr. Latanya Sweeney discuss their findings about algorithmic bias in Google search results and ads, and how it particularly affects women of color.

Content warning: The following video includes discussions of racism, sexism, and racial violence. It also shows sexualized images found in search results.

Video 38.2. Search Engine Breakdown: Are Algorithms Racist and Sexist? | Full Film by NOVA PBS

Research Exercise

One way to escape the algorithms: don’t let them tell you what sources to use. Instead, go straight to reputable sources on your topic. Some examples:

- If you’re researching climate change, the website for the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change might be a good place to look for reports.

- If you want to know if Instagram use is correlated with depression in teens, see what the American Academy of Pediatrics’ website has on this issue.

- If you want to know the latest news on a global conflict, go to the website for a news organization you trust, or use a site like Ground News that curates coverage from a variety of publications.

- If you want to see the latest scientific research on a topic, find a scholarly journal that focuses on that topic and browse the articles they’re publishing. You can use a tool like Browzine to follow particular journals, if it’s available through your library.

Activity: Use the Opposing Viewpoints database (if it’s available through your library), to identify relevant expert organizations whose websites you can explore directly (rather than relying on Google’s or TikTok’s algorithm to point you there!).

- Open the Opposing Viewpoints database.

- Search for your essay topic, or any current societal topic you’re interested in.

- If a topic guide comes up as you type in your search, click on it.

- Under “On this Page,” click the link for Websites.

- Go to some of the recommended websites and look around for some relevant research reports.

- Submit links to research reports from two different websites to your professor.

Saint Mary’s College of California Resources

SMC students, use these SMC Library links to access the resources mentioned above:

- Browzine journal browsing app

- Opposing Viewpoints database

Attributions

This chapter was adapted from Introduction to College Research, copyright © by Walter D. Butler; Aloha Sargent; and Kelsey Smith. Introduction to College Research licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Image: “Facebook Concept Binary” by geralt on Pixabay

Image: “Shell Sorting Algorithm Color Bars” by Balu Ertl is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Infographic: “Life in the Age of Algorithms” by Jessica Yurkofsky for Project Information Literacy is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Some text adapted from “Digital Citizenship” by Aloha Sargent and James Glapa-Grossklag for @ONE, licensed under CC BY 4.0

Works Cited

Head, Alison J., Barbara Fister, and Margy MacMillan. “Information Literacy in the Age of Algorithms.” Project Information Literacy, 15 Jan. 2020. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“How Google Search Works.” YouTube, uploaded by Google, 24 Oct. 2019.

“How biased are our algorithms? | Safiya Umoja Noble | TEDxUIUC.” YouTube, uploaded by TEDx Talks, 18 Apr. 2014.

Lee, Nicole Turner, Paul Resnick, and Genie Barton. “Algorithmic Bias Detection and Mitigation: Best Practices and Policies to Reduce Consumer Harms.” Brookings, 22 May 2019.

Rainie, Lee, and Janna Anderson. “Code Dependent: Pros and Cons of the Algorithm Age.” Pew Research Center, 8 Feb. 2017.

Media Attributions

- 512px-Shell_sorting_algorithm_color_bars.svg © balu.ertl is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- pil_algorithm-study_2020-01-15_algo-figure © jessica yurkofsky is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

Step-by-step instructions that computers follow to complete tasks, solve problems, and make automated decisions. Algorithms use data to make predictions about people, including their preferences, attributes, and behaviors. They power nearly everything we see online and are used to shape and filter content on the platforms we interact with daily.

Occurs when algorithms reinforce or even amplify racist, sexist, or other social biases.