17 The Research Process

Gina Kessler Lee

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to

- Diagram some basic steps in the research process

- Describe what you already know about your topic

- Pose research questions based on what you still need to know about your topic

- Identify keywords to find relevant information

- Decide what search tools to use for your research

In this chapter, we’ll walk through some strategies for getting started with research. (We’ll explore more nuances of the research process later in this book, in Writing to Make an Argument with Research.)

The Research Process

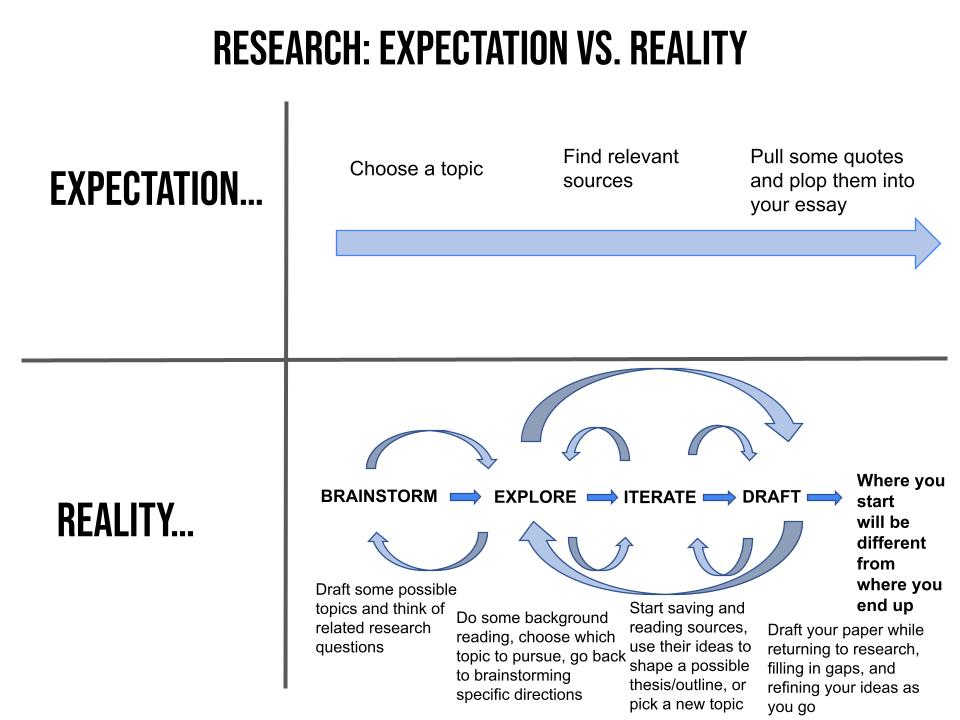

Now that we’ve established how research can help your writing, what does the process look like? The short answer is: it might be messier than you think.

Fig. 17.1. Research expectation vs reality flowchart [Image Description]

Whether you’re looking for your own sources or using texts provided by your professor, you can look to the information you have for inspiration on what to write about and how to structure your argument.

The Research Process

Start with What You Know

You may have chosen a topic you know a lot about, or perhaps you chose it precisely because you don’t know much and you’re curious to learn more. Either way, you should lay out what you bring to this topic before you start researching, and revisit the assumptions you started with as you progress through the research process.

Write to Learn: What You Already Know

Continue with Some Background Research

As you’re honing in on some specific topics and corresponding research questions, skim some basic background information. You may want to consider:

- What does Wikipedia say about your topic?

- What issues related to your topic have been in the news lately?

- How do basic explainer articles break down your topic into different subtopics or questions?

- What academic encyclopedia entries on your topic are available through your library?

- What books are out there on your topic? (Even if you don’t have time to read a whole book, skimming the titles and tables of contents can give you some ideas for how to approach your topic.)

Write to Learn: Background Information

This background research will help you refine your topic and answer some questions you had, but it can also help you come up with newer, better, deeper questions that your essay can explore.

Identify What You Don’t Know Yet

Identifying the gaps in your knowledge will help you to create research questions that will guide your research.

For instance, if you have decided to research the effects of divorce on children, after writing down what you do know about the topic, you’d next want to write down what you do not know but are curious to find out.

What I know:

- Divorce is common in the United States

- Sometimes children are negatively affected by their parents getting divorced

What I don’t know:

- Is there a certain age that children are more prone to the negative effects of divorce?

- Can children carry negative effects of divorce with them into adulthood?

- How can divorce impact academic performance?

- How can the effects of divorce be mitigated?

- In what cases might divorce have a positive effect on children’s mental health or development?

Write to Learn: What You Don’t Know Yet

Identify Keywords to Search for Information

When you’re looking for information on your topic, it’s important to consider what search terms you’re using. You might want to start broad with your search, and then as your ideas get more specific, you can make your search terms more specific too. For example, you might start with a general search on effects of divorce. Then, based on your background research, your next search might be for divorce high school academic performance.

Watch this video for some advice on brainstorming search terms, or keywords (view time is 2:23).

Video 17.1. Keywords for searching | NC State University Libraries by NC State University Libraries YouTube Channel

Google is pretty flexible, but precise keywords are especially important when you’re going to be searching a library database (more on this below). But even when you’re searching with Google, changing your search terms even slightly will usually bring up totally different results. Give it a try!

Keywords

Decide Where to Search

Now that you’ve got a research topic, some background information, some things you want to know, and some words to search with, where exactly should you search for sources?

In our everyday lives, we might turn to YouTube or TikTok for quick answers to everyday questions, like What are some cute hairstyles for curly hair? How do I get that smell out of the washing machine? Or, How should I choose a college major? (And increasingly, college students are using YouTube for learning [new tab] and using TikTok as their default search engine over Google [new tab].)

Still, many students turn to Google first for their research. It’s familiar, it’s easy to search, and it’s generally pretty good at bringing up sources that seem relevant to the questions we type in. But as we’ll address later in chapters on algorithms and evaluating websites, it’s got bias baked in, and often websites will game the rankings to get their less-than-authoritative site to appear near the top of your results. So it can be a starting place for your search, but you’ll want to try some other search engines too.

So, what are some other tools you can use to search? Here are a few starting places:

- Libraries have many different research databases that can point you to articles, books, videos, and data on your topic.

- Your college library probably has a search engine that searches a whole bunch of these databases at once. Look for a prominent search box on your library’s website.

- Google Scholar [new tab] is a search engine made by Google that brings up academic research rather than regular websites. When you’re looking for research studies, this can be an easy place to start. We’ll learn more about this later in the book.

- You might also look up which trustworthy news sites, nonprofits, or research organizations cover your topic, and search on their website. For example, maybe you’ll want to see if the American Academy of Pediatrics has any guidance on helping children deal with divorce.

Go Beyond Google: Other Sources of Information on Your Topic

Image Descriptions

Fig. 17.1 Image Description. The image is divided into four quadrants, illustrating the concept of “Research: Expectation vs. Reality.” The top half represents “Expectation,” with a horizontal timeline showing a straightforward process: “Choose a topic,” “Find relevant sources,” and “Pull some quotes and plop them into your essay,” indicated by a single straight arrow. The bottom half depicts “Reality,” with a cyclical and iterative process illustrated by curved arrows connecting four stages: “Brainstorm,” “Explore,” “Iterate,” and “Draft.” Below each stage, short descriptions are provided. To the top right, a note says, “Where you start will be different from where you end up,” highlighting the non-linear nature of actual research. [Return to Fig. 17.1]

Attributions

“Identify What You Don’t Know Yet” is from Introduction to College Research Copyright © by Walter D. Butler; Aloha Sargent; and Kelsey Smith, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Media Attributions

- Research expectation vs reality © Julie McPherson and Gina Kessler Lee is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Divorce © ChatGPT is licensed under a Public Domain license