11 Finding a Text to Rhetorically Analyze

Gina Kessler Lee

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to

- Identify types of texts that work better for rhetorical analysis

- Find a text for rhetorical analysis using library resources

Now you know how to analyze a text rhetorically. But how do you find a text that lends itself to rhetorical analysis?

Your instructor may have provided the text(s) they want you to analyze, but if not, you’ll need to find a text that makes your job of rhetorical analysis straightforward yet interesting. So here are some strategies to set yourself up for success.

Ignore all you’ve been told about finding credible, objective, and scholarly information.

While the author of even the blandest news report or scholarly study makes wording choices that you could analyze, a writer’s tactics will likely be easier to spot in an opinionated piece. So feel free to use a biased YouTube video, an opinion article from a newspaper, or a politician’s speech (as long as your instructor says this is okay).

The most important thing for this kind of assignment usually isn’t whether your text is unbiased. Instead, your task (depending on your instructor’s requirements) is to

- identify the biases and assumptions,

- situate your source in the exigence, audience, and constraints, and

- point to specific examples of how the author uses pathos, logos, and ethos to make their case, even if it’s biased.

Make sure any text you choose allows you to accomplish those three tasks.

Don’t overwhelm yourself with a text that’s too long.

For most assignments, using a book, a two-hour film, or a 30-page scholarly article is great. But for this kind of analysis, using a shorter piece will allow you to really dig into the rhetorical choices made in each word, sentence, and paragraph.

Choose a text that’s significant.

While you could analyze any rando’s TikTok, it’ll be easier to identify the rhetorical situation if you can research a bit about the author, the publication or setting, and any constraints they may be under. Plus, it’ll be more interesting to your reader if you can call out the rhetorical strategies of a powerful senator, prominent business executive, or highly influential YouTuber rather than some kid down the street (unless that kid’s post has gone viral and become the voice of their generation).

Choose a more argumentative genre.

Texts in some genres tend to be more straightforward. Others lend themselves to making arguments that give you more to work with. You might consider using a:

- speech

- contributor opinion from the opinions section of a newspaper

- thread on X, Threads, or BlueSky

- video essay on YouTube

A news article that just says “this event happened on this day at this time and here’s what people on both sides had to say about it” might not offer as much of an obvious voice for you to analyze.

Don’t just rely on a Google search.

Head to a database or publication where you know you will be able to find these sorts of genres, such as:

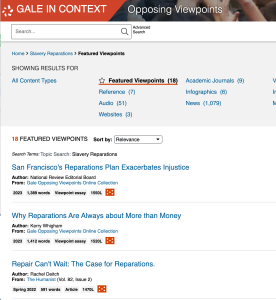

Opposing Viewpoints

Gale in Context: Opposing Viewpoints is a database available through some libraries that curates—you guessed it—opposing viewpoints on different hot-button issues. Choosing a “featured viewpoint” in Opposing Viewpoints on a topic that interests you will save you the work of looking through Google search results to try to figure out if the articles it’s showing you are making arguments. The featured viewpoints will often usually come with an introduction that tells you a bit about the author and provides some questions to think about.

Vital Speeches of the Day

Vital Speeches of the Day magazine pulls together some of the most important speeches in English from around the world each month.

Instead of searching Google for “best speeches,” try browsing some of the more recent speeches curated in this magazine, by leaders ranging from Vladimir Putin to Mark Zuckerberg, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Greta Thunberg.

New York Times: Opinion section

Most newspapers have an opinion section where they post essays by columnists and guests expressing an opinion supported by evidence. Often, these authors are prominent leaders and thinkers who are invited by the opinion editors to contribute their viewpoint on a topic.

Saint Mary’s College of California Resources

SMC students, these SMC Library links will take you to the sources mentioned above:

- Opposing Viewpoints [new tab] database

- Vital Speeches of the Day [new tab] magazine

- New York Times [new tab] news website (create a login to take advantage of SMC’s digital subscription)

Select an argumentative text to analyze

Writing Our Bodies

Reflect on how choosing a text for rhetorical analysis might connect to our experiences as writing bodies:

- Consider the author’s and audience’s embodied experiences as part of the context for the text you choose. A speech is delivered and experienced differently than, say, an anonymous Reddit post. And the experience of delivering a speech to a large crowd is probably going to be different for a tall, able-bodied white man in a position of power than it is for a woman of color in a wheelchair.

- Notice the sensations your body experiences as you read viewpoints that are similar to or different from yours. Do you feel validation, rage, unease, or disgust? Acknowledge these feelings, and remind yourself that the point of your essay is not to argue with your text, but to identify how and why it was written to produce particular responses in the audience.

Media Attributions

- Gale Opposing Viewpoints Reparations Viewpoints

- New York Times Opinion screenshot