37 Finding sources: Choosing your search terms

Gina Kessler Lee

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to

- Choose search terms that will bring up relevant information on your topic

- Refine your search terms based on the research you’ve found

Language is personal

People in different disciplines have their own jargon and terminology for discussing their field and the ideas they work with. You must know how to decode this language in order to be able to talk to experts, understand what they are writing, and make the material clear for the non-specialist audience that will see the final message.

The language of a topic is also the key that opens the door to effective searching. Language is the access code through which formal collections of information in libraries and databases are indexed and organized. In addition, terminology shifts over time with the introduction of new words and as some language falls out of use and is replaced.

Political perspectives also play a role in decoding language. A body of water in the Middle East is called the Persian Gulf by some and the Arabian Gulf by others, depending on their political perspective. Think about the different connotations of the terms “pro-choice” or “pro-abortion;” “right-to-life” or “anti-choice.” You must understand how the audience will react to language and terminology choices. During your information search, you must use appropriate terminology to locate relevant information.

Finding relevant sources depends on your keywords

Two of the most important factors that influence whether we find useful and credible sources are:

- where we search (for example, Google, Google Scholar, YouTube, TikTok, Library Search, a specialized library database, or a specific website)—which you may have learned about in the chapter on The Research Process)

- what words we use to search

The following video (also included in the chapter on The Research Process) gives some short tips for identifying those words that we use in our online searches, also known as keywords (view time is 2:23):

Video 37.1. Keywords for searching \ NC State University Libraries by NC State University Libraries YouTube Channel

Research can help you find keywords

For example, let’s say you’re interested in exploring the privacy implications of parents sharing their kids’ photos and information on social media. Let’s map out some potential search terms, or keywords, that we could use to find information on this. Let’s make a bubble map together—I’ll start one on my topic, and you start one on yours (online or on paper):

Fig. 37.1. Beginnings of a brief bubble map or mind map about parents posting about their kids [Image Description]

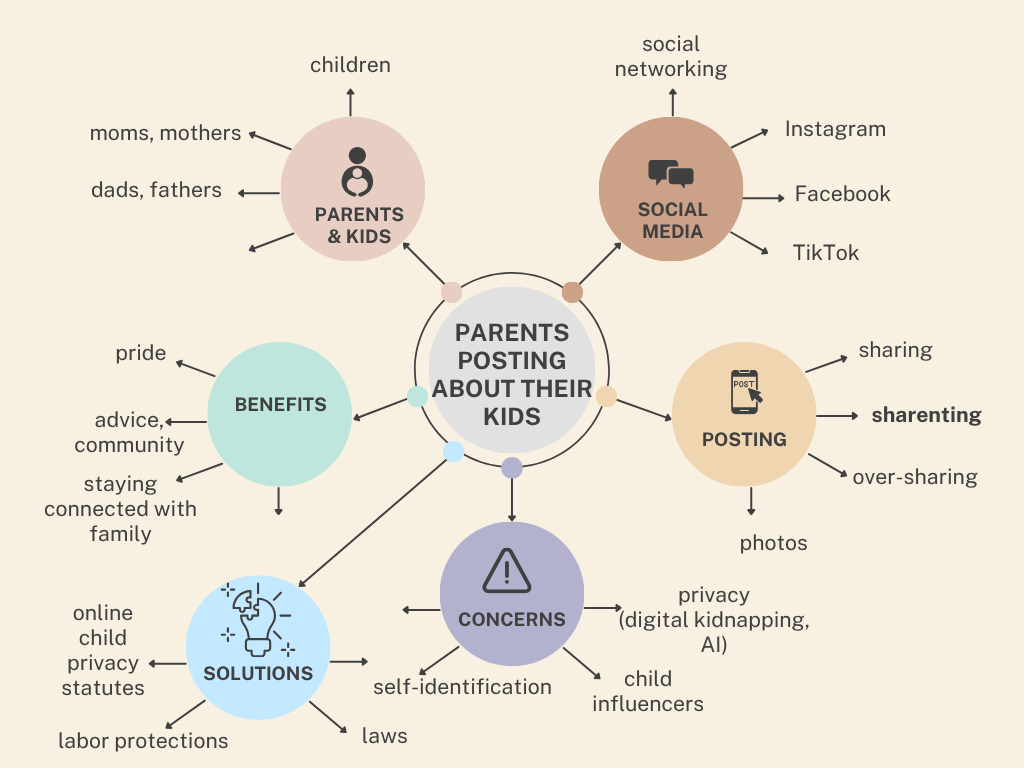

Now, these are just the words I thought of off the top of my head. How do I make my keywords more specific? Try these strategies:

- Do a Google search. What important words come up frequently on this topic? For example, I learn that there’s a word for parents sharing information about their kids on social media: sharenting.

- Find an encyclopedia or Wikipedia entry on your topic. What terms does it use to talk about your topic? What narrower subtopics or examples does it bring up? Add those words to your map, grouped with similar concepts.

- Look up synonyms for your topic. For example, a synonym for social media could be social networks. Consider what terms different groups of people might use for your topic, too.

- Think of some examples of each of the terms you already have. For example, some examples of social media services where “sharenting” happens are Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, and Douyin (what TikTok is branded in China).

- Do a search with the words you already have in Google Scholar or a Library database. What other related terms appear in related sources’ titles, keywords, or subject headings? For example, from this article and others I got self-presentation, online identities, influencer marketing, and moral attitudes.

As you search around, reading some background sources like encyclopedia entries, and getting a sense of what scholars talk about when they talk about this issue, add more keywords to your map:

Fig. 37.2. A more robust bubble map about parents posting about their kids [Image Description]

Now we can use different combinations of these words to try out multiple searches in multiple places and see which combinations prove most successful. For example, I could try:

- a Google search for parent social media sharing children privacy

- a Google Scholar search for sharenting adolescent perspectives

- a Communication Abstracts database search for (“social media” OR Instagram OR TikTok OR Facebook) AND privacy AND parenting

- a New York Times search for child influencers

And each of these searches will bring me different kinds of sources on this topic.

Keywords

Keywords vs. Subject Headings

Above, in Step 5 for expanding your keywords, I mentioned looking at the subject headings used by a library database to describe relevant articles on your topic. But what are these subject headings, how are they different from keywords, and who chooses them?

A “keyword” can be a word that appears in any part of a source, and might not be the same term someone else would use for that concept. A “subject heading,” however, is decided on by the editors of a database or classification system as the preferred term for that concept.

A major characteristic of information searching is the use of subject terms or headings. The major purpose of subject headings systems is to provide a standardized method of describing all information in the same general subject area so that everything pertaining to a topic can be identified. When you are searching for information in print or digital form, you are likely to have a general notion of the topic area you are researching rather than a detailed list of authors or titles of materials you are seeking. For that reason, information catalogers and indexers have tagged records with subject headings as a finding tool.

Indexers spend enormous amounts of time developing subject headings that accurately reflect the structure of information in a subject area. You can use these subject headings in many ways. They appear on the records in a library’s catalog; they appear in the entries of indexes and the headings in abstracts, or they may be used to organize material on websites.

Many libraries use the subject classification system created by the Library of Congress, a system that is called the Library of Congress Subject Headings.

Subject Headings and Identity: A Story of Student Activism

As we’ve seen throughout this book, writing and research are both shaped by our identities. But what happens when the system that you’re required to use for research uses a pejorative term for an aspect of your identity?

In 2014, Dartmouth College student Melissa Padilla, at the time undocumented herself, was doing research in the library catalog (Aguilera). She noticed the sources she was finding were classified with the subject heading “illegal aliens,” even when the sources themselves didn’t use that term. She brought the issue to her fellow activists at Dartmouth Coalition for Immigration Reform, Equality, and DREAMERs (CoFIRED), and they approached the library about changing the terms. However, the librarians informed them that those terms were not determined by the library, but by the Library of Congress—and they partnered with CoFIRED to petition the Library of Congress to replace “illegal alien” with “undocumented immigrants.”

But that wasn’t the end of the story: the Library of Congress denied their petition, writing, “Illegal aliens is an inherently legal heading, and as such, the preference is to use the legal terminology” (Library of Congress). After the American Library Association approved a resolution supporting the change, the Library of Congress changed its mind and agreed to update the term “illegal aliens.” But before the changes went into effect, Republican lawmakers got wind of this change and tried to prevent the Library of Congress from removing the term; however, this stipulation didn’t make it into the final version of the bill (Aguilera). Finally, in 2021, seven years after the students’ fight for a respectful and accurate subject heading began, the Library of Congress replaced the term “illegal aliens” with two new subject headings: “noncitizens” and “illegal immigration” (“ALA Welcomes Removal”).

Below, watch the trailer for Change the Subject, a documentary on these students’ fight (view time 2:38), or view the whole film online.

Video 37.2. ‘Change the subject’ trailer by Change the Subject

Image Descriptions

Fig. 37.1 Image Description. The image is a concept map depicting the theme “Parents Posting About Their Kids”. At the center, a circle labeled “PARENTS POSTING ABOUT THEIR KIDS” connects with five surrounding nodes through solid lines. These nodes are each a different color, forming a network. Starting clockwise from the top: 1. A beige circle labeled “SOCIAL MEDIA” with speech bubble icons. 2. A light orange circle labeled “POSTING” with an icon of a hand pressing a “post” button, and the word “sharing” emanating from it. 3. A lavender circle labeled “CONCERNS” with a caution symbol and the term “privacy”. 4. A light teal circle without a specific label, with arrows pointing outward from it in multiple directions without specific terms. 5. A dusty pink circle labeled “PARENTS & KIDS” with an icon of an adult and child figure, with arrows labeled “children” and “moms”. [Return to Fig. 37.1]

Fig. 37.2 Image Description. The image is an infographic illustrating the topic “Parents Posting About Their Kids.” At the center is a circle labeled “PARENTS POSTING ABOUT THEIR KIDS,” connected by lines to five surrounding circles representing different themes: “PARENTS & KIDS,” “SOCIAL MEDIA,” “POSTING,” “CONCERNS,” and “BENEFITS.” Each circle features relevant sub-topics. The top circle titled “PARENTS & KIDS” includes sub-topics: children, moms, mothers, dads, fathers. On the right, “SOCIAL MEDIA” lists social networking, Instagram, Facebook, TikTok. Below, “POSTING” includes sharing, sharenting, over-sharing, photos. On the bottom left, “CONCERNS” features privacy (digital kidnapping, AI), child influencers, self-identification, laws. The left circle “SOLUTIONS” lists online child privacy statutes, labor protections, regulations. The top left circle “BENEFITS” includes pride, advice, community, staying connected with family. [Return to Fig. 37.2]

Attributions

Portions of this chapter were adapted from Information Strategies for Communicators Copyright © 2015 by Kathleen A. Hansen and Nora Paul, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Works Cited

Aguilera, Jasmine. “Another Word for ‘Illegal Alien’ at the Library of Congress: Contentious.” New York Times, 22 July 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/23/us/another-word-for-illegal-alien-at-the-library-of-congress-contentious.html.

“ALA Welcomes Removal of Offensive ‘Illegal aliens’ Subject Headings.” American Library Association, 12 Nov. 2021, https://www.ala.org/news/2021/11/ala-welcomes-removal-offensive-illegal-aliens-subject-headings. Press release.

Library of Congress, Program for Cooperative Cataloging, Subject Authority Cooperative Program. “Summary of Decisions, Editorial Meeting Number 12.” Library of Congress, 14 Dec. 2014, https://www.loc.gov/aba/pcc/saco/cpsoed/psd-141215.html.

Media Attributions

- Sharenting Bubble Map 1 © Gina Kessler Lee is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Sharenting Bubble Map 2 © Gina Kessler Lee is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Keywords vs subject headings © Gina Kessler Lee is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license