19 How Revising is Different from Editing

Yin Yuan

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to

- Identify how revision is different from editing

- Use different revision strategies depending on the stage of your draft

In the Write to Learn below, reflect on your own revision process.

Write to Learn: Your Revision Process

As noted in the last chapter, revision is re-vision: that is, to see anew. In this chapter, we will consider how you can take an existing draft and further develop it in order to better meet the expectations of its rhetorical situation. Some questions you might ask to guide your revision process include:

- What new information can you discover as you revise?

- How can you add new information to what you’ve already written?

- What challenges did you encounter, and how might you respond to those challenges in writing to strengthen the piece?

- What linguistic, rhetorical, design, or other devices can you experiment with to engage your reader?

Before you can do so, however, you need to have written your first draft; you need something substantive to work with. As Jodi Picoult, a successful American novelist, says, “You can’t edit a blank page” (Kramer). Another writer, Anne Lamott, reminds us that early drafts aren’t perfect. These points are both spot on. You need a working draft for revision, even if that draft is far from perfect.

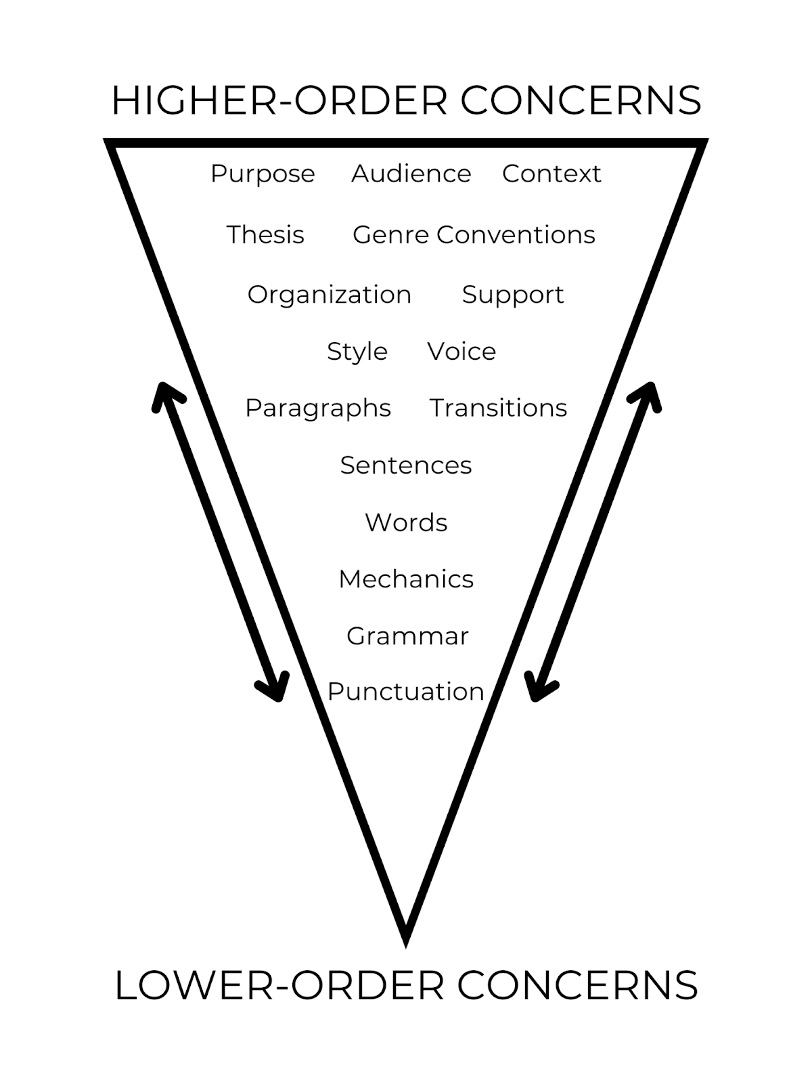

Furthermore, revision is more than just editing or proofreading; revision requires critical thinking, feedback, and a careful examination of our work. Note that we said examination. Revision is not a quick scan of your work for errors like comma problems, misspelled words, or other low-order concerns (LOCs). That’s editing and proofreading. Revision means looking at your work as a whole, taking notes of all its parts, their overall effectiveness, and other HOCs. (Fig. 19.1 [Image Description]).

Revision, in other words, means examining such concerns as organization, argument/thesis, purpose, audience, and supporting evidence. It is difficult, if not impossible, to revise without considering these components, which we call higher-order concerns (HOCs) because these components have a bigger impact on the overall effectiveness of any composition. Lower-order concerns or LOCs, on the other hand, affect the overall appearance, polish, and clarity of the composition.

In this chart, the most significant HOCs are purpose, audience, and context; as outlined in the chapter on rhetoric, these three form the rhetorical situation. It’s critical to make sure these elements (purpose, audience, and context) are clear and effective. Of nearly equal importance are the thesis or argument and genre conventions.

Here are some strategies for considering the HOCs in approaching an early draft. When considering an early draft, you are still trying to identify and develop your central argument. You are looking out for compelling moments where the thesis comes through and intriguing places where you can develop further.

Early draft questions

Purpose + Context

- Why was this assignment given? What is it trying to assess? How has your paper sought to demonstrate those skills?

- What are the learning goals/objectives of this assignment? Has your paper effectively accomplished these goals?

Audience

- Who are you writing for? What different social locations does this audience occupy?

- What are the expectations/needs of this audience, and how might you try to appeal to those expectations and needs through your compositional choices?

Thesis

- What is the central idea (“thesis) of this paper, and does it address the key assignment prompt?

- Is the thesis specific (“clearly defined,” “exhibits depth and complexity in its analysis”)? Can you use break down concepts further?

- Is the thesis arguable (demonstrates an “intellectually challenging focus,” shows “originality”)? Can you play devil’s advocate and consider what an opposing argument might look like?

- Is the thesis significant (displays a “strong sense of purpose and audience” in anticipating the “so what” question)?

Evidence/Analysis

- Do you make specific claims that are supported by concrete and relevant evidence?

- Annotate the places where you find the most effective use of evidence. How might you build upon this evidence and analysis to create a new argument?

- Annotate the places where you think more evidence or concrete examples are needed, and consider how you might provide support for their claims.

New Directions

- What is the most intriguing moment in your essay—the place that leaves you with a desire to know more? How might you develop this into a question that you can answer through a revised thesis?

- What moments in your essay create the strongest, most vivid sensations for you in your body? Why? How might you develop those moments?

Once you have gone through your own early draft review, peer reviews, and any other read-throughs and analyses of your draft, you may be ready for the final stage of revision. This is still not simply editing—checking for misspelled words or missing commas.

Once again, you have the opportunity to “re-see” your paper, to look closely and deeply at it to make sure that it is making sense, that it flows, and that it is meeting the core assignment requirements. Instead of completely re-envisioning the paper, now you want to focus on evidence and organization in order to make the argument come through more clearly.

Late Draft Questions

Introduction/Thesis

- Does the introductory section provide context for and lead up to the central idea (“thesis”) of this paper?

- How might you grab the reader’s attention with your opening?

- What is the exigency for your piece? How can you draw your reader’s attention to that context and appeal to their sense of urgency?

Evidence/Analysis

- Do you effectively describe the object of analysis—i.e., would the reader who does not know this object be able to come away with a clear understanding of that object?

- What claims would require more evidence and/or analysis?

- Where do you summarize, paraphrase, and quote, and is it effective? Are there places that you might use summary more? Are there places where you might analyze more?

- Are you engaging with required source materials as much or as deeply as you need to be? Would your paper be stronger if you reread the sources another time to better understand them? Do you need more source support in the paper? Do you need to enhance your source integration (signal phrases, citations)?

Organization

- Does the paper have a clear argumentative trajectory—a sequence of ideas that connect to each other, and which come together to form the central argument?

- Does each paragraph open with a bridge sentence that connects to the point raised in the preceding paragraph?

- Is each paragraph organized around one central idea?

- Please highlight key ideas, and use a different color to highlight ideas that are disconnected or abrupt, and which should be moved to a different place in the paper.

Conclusion

- How does the conclusion differ from the introduction? Does it restate the introduction, or does it leave the reader with new insights?

- Does it explore implications—i.e., why the argument matters?

- Think about the conclusion like arriving at the top of a hill after making the climb up (the climb up is the essay). Now that you are at the top, what do you see differently from where you were before?

Feedback

- Based on readerly feedback—peer reviewers, tutors, your instructor, friends, etc., where can you make your essay more reader-friendly? Where does it need more effort and focus?

- Often, we make consistent errors in our writing from paper to paper. Read over feedback from other papers—even from other classes—and review your paper with special attention to those errors. There is still time to come talk to your professor about fixing them if you don’t understand how to avoid them!

Revision is an important stage in the writing process. It takes time and persistence. It also gets easier with practice. Experienced writers see revision not only as important, but as the central part of writing. First drafts, to quote Lamott again, are “shitty”—a way to get out tentative ideas that can only reveal their potential through the process of revision. Writing is a recursive process; you can revisit earlier steps in your process before, during, and after revising. In the end, however, revision helps us develop effective writing habits. Revision also helps us understand ourselves as writers and communicators by providing an opportunity to reflect on our purpose in writing how well we achieve our purpose. Therefore, plan to make revision a central part of your writing process every time you write.

Image Descriptions

Fig. 19.1 Image Description. The image features an inverted triangle with a black border, illustrating a hierarchy of writing and editing concerns. At the top inside the triangle, labeled as “Higher-Order Concerns,” are elements like Purpose, Audience, Context, Thesis, Genre Conventions, Organization, Support, Style, and Voice. Lower inside the triangle are “Lower-Order Concerns,” including Paragraphs, Transitions, Sentences, Words, Mechanics, Grammar, and Punctuation. Arrows on both sides of the triangle indicate movement from higher-order to lower-order concerns. [Return to Fig. 19.1]

Attributions

“Revising Your Drafts,” in A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing, Melanie Gagich and Emilie Zickel, CC Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 4.0

“Revising,” in First-Year Composition: Writing as Inquiry and Argumentation, Jackie Hoermann-Elliott and Kathy Quesenbury, CC Attribution 4.0