9 What Is Rhetoric? What Is Rhetorical Analysis?

Yin Yuan

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to

- Define “rhetoric”

- Identify the various components of the rhetorical situation

- Analyze a text by considering its rhetorical appeals

What is rhetoric?

Is rhetoric manipulation? False advertisement? Sheer bulls***?

Rhetoric can be any or all of these things, but it is also much more than that. Any time anybody (any body, with the specific lived experiences of that raced, gendered, class-ed body) makes a decision to communicate a message, rhetoric is in play. Any time you say, write, and/or behave in a particular way, whether actively conscious of the purpose or not, you are making decisions about your body language, about which words to use, and about what tone to establish based upon what is appropriate for your intended audience in that context. That is rhetoric.

The American Heritage Dictionary online defines “rhetoric” as “the art or study of using language effectively and persuasively.” But language does not only have to be words on a page. As the phrase “body language” suggests, how you present and carry your body is also a kind of “language” because it presents signs that audiences can interpret.

Even if the concept “rhetoric” sounds abstract, every one of us knows how to use it. Let’s try it out using an exercise that rhetoric professor Janet Boyd devised for her students.

Murder! (Rhetorically Speaking)

Five Simple Facts

Who: Mark Smith

What: Murdered

Where: Parking garage

When: June 6, 2019; 10:37pm

How: Multiple stab wounds

You might read such straightforward facts in a short newspaper article or hear them in a brief news report on the radio; if the person was not famous, the narrative might sound like this: Mark Smith was found stabbed to death at 10:37 p.m. on June 6th, in the local parking garage.

Next, each of you will be assigned a mysterious role through which you will respond to these five simple facts. Please only click on the dropdown for your role, and not for any of the others. You will follow the instructions for your role and write down your answer on our collaborative class document.

After everybody has completed their assigned task, please reflect on your process of completing the task:

- How does the report/document begin? Where does it end?

- What types of details did you find yourself adding? Why? What details did you omit? Why?

- What kind of words did you choose?

- What tone did you take? (I will admit, tone can be a tricky thing to describe; it is best done by searching for a specific adjective that describes a feeling or an attitude such as “pretentious,” “somber,” “buoyant,” “melancholic,” “didactic,” “humorous,” etc.).

- How did you order your information?

- How did you know how to write like a person in your role would in the first place?

Identify one other entry on the class doc that you think shares your same role. What makes you think so? What similarities do you observe between your entries? We will repeat this same series of steps for all the mysterious roles. Then, let’s analyze the similarities and differences across the different roles. What do you notice?

One key reason why you had little trouble fulfilling your task–the reason why you intuitively knew how to begin, what types of details to include, what kinds of words to choose, and what tone to adopt—is because you are familiar with the genre that you are writing in. Here is a definition of “genre”: when the traits or attributes considered normal to or typical of a particular kind of creative piece, such as in literature, film, or music, make it that kind and not another. For example, we know horror films when we see them, and we recognize classical music when we hear it because we can classify these things according to the conventions of their genres.

You know how to write like a detective presumably because you have watched TV shows like CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, which offer us a glimpse not only into the work detectives are likely to do but also the language they choose. Gradually, and ever so subtly, we internalize this detectivespeak, which is more than just the jargon they use. Jargon is the terminology used by those in a particular profession or group to facilitate clear and precise communication, but this rhetorical tool is not limited just to the professional world. For example, anyone who participates in a sport uses the lingo specific to that sport, which is learned by doing. Doctors use medical jargon and lawyers use legal jargon, and they go to school specifically to learn the terms and abbreviations of their professions; so do detectives.

Based on this activity, let us consider once again what rhetoric means. Rhetoric is what allows you to write (and speak) appropriately for a given situation, one that is determined by the expectations of your audience, implied or acknowledged, whether you are texting, writing a love letter, or bleeding a term paper. When you go to write, you might not always be actively aware of your audience as an audience. You may not even consciously realize that you are enacting certain rhetorical strategies while rejecting others. But each time you write, you will find yourself in a rhetorical situation—in other words, within a context or genre—that nudges you to choose the right diction or even jargon and to strike the right tone. The fact that you are able to fulfill the task given to you shows the extent to which we absorb and internalize our rhetorical tools by watching media, reading books, and participating in our culture.

Understanding the rhetorical situation

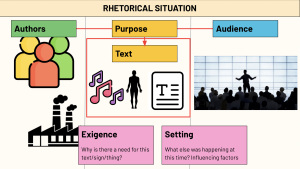

A key component of rhetorical analysis involves thinking carefully about the “rhetorical situation” of a text. You can think of the rhetorical situation as the context or set of circumstances out of which a text arises. Any time anyone is trying to make an argument, one is doing so out of a particular context, one that influences and shapes the argument that is made. When we do a rhetorical analysis, we look carefully at how the rhetorical situation (context) shapes the rhetorical act (the text). Note that the text doesn’t only have to be a written document. It can be an image, a song, a space, or a body.

We can understand the concept of a rhetorical situation if we examine it piece by piece, by looking carefully at the rhetorical concepts from which it is built. Drawing on classical and contemporary rhetoricians such as Aristotle and Keith Grant-Davie, we will define these concepts as: exigence, author, audience, setting, and text. Answering the questions about these rhetorical concepts below will give you a good sense of your text’s rhetorical situation—the starting point for rhetorical analysis.

Exigence

The Oxford English Dictionary defines exigence as “what is needed or required; a thing wanted or demanded; a requirement, a necessity.” In the context of rhetorical situations, exigence refers to the motivating factor that spurred the creation of the text. A problem requiring a solution must have existed, and to solve the problem, someone created a text. That problem is the exigence.

When considering exigence, you should ask the following questions:

- What is the topic of the text?

- Why is this text needed at this moment? What problem is the text trying to resolve?

- What are the goals of the text? What is it trying to accomplish?

Author

The “author” of a text is the creator—the person who is communicating in order to try to effect a change in his or her audience. An author doesn’t have to be a single person or a person at all—an author could be an organization. To understand the rhetorical situation of a text, one must examine the identity of the author and their background.

- Who is the author, and how does their body affect their lived experience? In creating the text, are they making their body visible or invisible? How does that serve their purpose?

- What kind of experience or authority does the author have in the subject about which he or she is speaking?

- What values does the author have, either in general or with regard to this particular subject?

- How invested is the author in the topic of the text? In other words, what affects the author’s perspective on the topic?

- Are there other people or institutions who may have played a role in shaping the text?

- What is the author’s persona? That is, what is the identity he is trying to project as the creator of this text?

Audience

In any text, an author is attempting to engage an audience. Before we can analyze how effectively an author engages an audience, we must spend some time thinking about that audience. An audience is any person or group who is the intended recipient of the text and also the person/people the author is trying to influence. There might be multiple audiences the author is trying to reach simultaneously—they can thus be broken down into primary audience, secondary audience, etc.

To understand the rhetorical situation of a text, one must examine who the intended audience is by thinking about these things:

- Who is the author addressing?

- Sometimes this is the hardest question of all. We can get this information of, “who is the author addressing” by looking at where an article is published. Be sure to pay attention to the newspaper, magazine, website, or journal title where the text is published. Often, you can research that publication to get a good sense of who reads that publication.

- What is the audience’s demographic information (age, gender, etc.)?

- What is/are the background, lived experiences, values, or interests of the intended audience?

- How open is this intended audience to the author?

- What assumptions might the audience make about the author?

- In what context and/or space is the audience receiving the text?

Grant-Davie distinguishes the intended audience from the invoked audience. If the intended audience is who the author is trying to reach, the invoked audience is a constructed (often idealized) identity that the author is trying to persuade the audience into accepting. For instance, a political campaign poster may be directed at undecided voters. They are the the intended audience. The invoked audience may be someone who will vote for the candidate because they recognize the importance of the candidate’s platform on a particular issue.

Setting

Nothing happens in a vacuum, and that includes the creation of any text. Essays, speeches, photos, political ads—any text—was written in a specific time and/or place, and the people, events, and objects that are part of this setting. In considering setting, you are considering how these contextual factors may influence how the author is trying to appeal to the audience through the text.

Here are some questions to consider:

- What are some contemporary events that may influence the way the text is received?

- Are there other texts with which the particular text we are considering is competing?

Text

At the center of the rhetorical situation is the text: the document that the author has created in response to a particular problem, intended for a particular audience, and with the goal of achieving certain outcomes. The various constituents of the rhetorical situation are there to help us analyze how the text tries to accomplish its goals. This means paying attention to textual features such as genre, medium, rhetorical appeals, and figures of speech.

Remember once again that the text does not have to be merely linguistic. It can be an image, a song, a space, a material object, a body, or more.

How to do rhetorical analysis

The goal of a rhetorical analysis is to explain what is happening in the text, why the author might have chosen to use a particular move or set of rhetorical moves, and how those choices might affect the audience. The text you analyze might be explanatory, although there will be aspects of argument because you must negotiate with what the author is trying to do and what you think the author is doing. Edward P.J. Corbett observes, rhetorical analysis “is more interested in a literary work for what it does than for what it is” (qtd. in Nordqvist).

One of the elements of doing a rhetorical analysis is looking at a text’s rhetorical situation. The rhetorical situation is the context out of which a text is created.

Another element of rhetorical analysis is simply reading, summarizing, and/or otherwise describing the text. You have to be able to describe the basics of the message before you can begin to analyze it.

A third element of rhetorical analysis requires you to connect the rhetorical situation to the text. You need to go beyond summarizing and look at how the author shapes their text based on its context. In developing your reading and analytical skills, allow yourself to think about what you’re reading, to question the text and your responses to it, as you read. Use the following questions to help you take the text apart—dissecting it to see how it works:

- Does the author successfully support the thesis or claim? Is the point held consistently throughout the text, or does it wander at any point?

- Is the evidence the author used effective for the intended audience? How might the intended audience respond to the types of evidence that the author used to support the thesis/claim?

- What rhetorical moves do you see the author making to help achieve their purpose? Are there word choices or content choices that seem to you to be clearly related to the author’s agenda for the text or that might appeal to the intended audience?

- Describe the tone in the piece. Is it friendly? Authoritative? Does it lecture? Is it biting or sarcastic? Does the author use simple language, or is it full of jargon? Does the language feel positive or negative? Point to aspects of the text that create the tone; spend some time examining these and considering how and why they work. (Learn more about tone in Open Oregon’s The Word on Reading and Writing’s chapter, “Tone, Voice, and Point of View.”)

- Is the author objective, or do they try to convince you to have a certain opinion? Why does the author try to persuade you to adopt this viewpoint? If the author is biased, does this interfere with the way you read and understand the text?

- Do you feel like the author knows who you are? Does the text seem to be aimed at readers like you or at a different audience? What assumptions does the author make about their audience? Would most people find these reasonable, acceptable, or accurate?

- Does the text’s flow make sense? Is the line of reasoning logical? Are there any gaps? Are there any spots where you feel the reasoning is flawed in some way?

- Does the author try to appeal to your emotions? Does the author use any controversial words in the headline or the article? Do these affect your reading or your interest?

- Do you believe the author? Do you accept their thoughts and ideas? Why or why not?

Rhetorical appeals

Logos: Appeal to Logic

![]()

Logic. Reason. Rationality. Logos is brainy and intellectual, cool, calm, collected, objective.

When an author relies on logos, it means that he or she is using logic, careful structure, and objective evidence to appeal to the audience. An author can appeal to an audience’s intellect by using information that can be fact-checked (using multiple sources) and thorough explanations to support key points. Additionally, providing a solid and non-biased explanation of one’s argument is a great way for an author to invoke logos.

For example, if I were trying to convince my students to complete their homework, I might explain that I understand everyone is busy and they have other classes (non-biased), but the homework will help them get a better grade on their test (explanation). I could add to this explanation by providing statistics showing the number of students who failed and didn’t complete their homework versus the number of students who passed and did complete their homework (factual evidence).

Logical appeals rest on rational modes of thinking, such as

- Comparison – a comparison between one thing (with regard to your topic) and another, similar thing to help support your claim. It is important that the comparison is fair and valid—the things being compared must share significant traits of similarity.

- Cause/effect thinking – you argue that X has caused Y, or that X is likely to cause Y to help support your claim. Be careful with the latter—it can be difficult to predict that something “will” happen in the future.

- Deductive reasoning – starting with a broad, general claim/example and using it to support a more specific point or claim.

- Inductive reasoning – using several specific examples or cases to make a broad generalization.

- Exemplification – use of many examples or a variety of evidence to support a single point.

- Elaboration – moving beyond just including a fact, but explaining the significance or relevance of that fact.

- Coherent thought – maintaining a well-organized line of reasoning; not repeating ideas or jumping around.

Pathos: Appeal to Emotions

When an author relies on pathos, it means that they are trying to tap into the audience’s emotions to get them to agree with the author’s claim. An author using pathetic appeals wants the audience to feel something: anger, pride, joy, rage, or happiness. For example, many of us have seen the ASPCA commercials that use photographs of injured puppies, or sad-looking kittens, and slow, depressing music to emotionally persuade their audience to donate money.

Below is an example of an ASPCA commercial that uses image and music to evoke feelings of sympathy in the audience:

Pathos-based rhetorical strategies are any strategies that get the audience to “open up” to the topic, the argument, or to the author. Emotions can make us vulnerable, and an author can use this vulnerability to get the audience to believe that his or her argument is a compelling one.

Pathetic appeals might include

- Expressive descriptions of people, places, or events that help the reader to feel or experience those events

- Vivid imagery of people, places, or events that help the reader to feel like he or she is seeing those events

- Sharing personal stories that make the reader feel a connection to, or empathy for, the person being described

- Using emotion-laden vocabulary as a way to put the reader into that specific emotional mindset (what is the author trying to make the audience feel? and how are they doing that?)

- Using any information that will evoke an emotional response from the audience. This could involve making the audience feel empathy or disgust for the person/group/event being discussed, or perhaps connection to or rejection of the person/group/event being discussed.

When reading a text, try to locate when the author is trying to convince the reader using emotions because, if used to excess, pathetic appeals can indicate a lack of substance or emotional manipulation of the audience. See the links below about fallacious pathos for more information.

Ethos: Appeal to Values/Trust

Ethical appeals have two facets: audience values and authorial credibility/character.

On the one hand, when an author makes an ethical appeal, they are attempting to tap into the values or ideologies that the audience holds, for example, patriotism, tradition, justice, equality, dignity for all humankind, self preservation, or other specific social, religious or philosophical values (Christian values, socialism, capitalism, feminism, etc.). These values can sometimes feel very close to emotions, but they are felt on a social level rather than only on a personal level. When an author evokes the values that the audience cares about as a way to justify or support their argument, we classify that as ethos. The audience will feel that the author is making an argument that is “right” (in the sense of moral “right”-ness, i.e., “My argument rests upon the values that matter to you. Therefore, you should accept my argument”). This first part of the definition of ethos, then, is focused on the audience’s values.

On the other hand, this sense of referencing what is “right” in an ethical appeal connects to the other sense of ethos: the author. Ethos that is centered on the author revolves around two concepts: the credibility of the author and their character.

Credibility of the speaker/author is determined by their knowledge and expertise in the subject at hand. For example, if you are learning about Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, would you rather learn from a professor of physics or a cousin who took two science classes in high school thirty years ago? It is fair to say that, in general, a professor of physics would have more credibility to discuss the topic of physics. To establish their credibility, an author may draw attention to who they are or what kinds of experience they have with the topic being discussed as an ethical appeal (i.e., “Because I have experience with this topic—and I know my stuff!—you should trust what I am saying about this topic”). Some authors do not have to establish their credibility because the audience already knows who they are and that they are credible.

Character is another aspect of ethos, and itis different from credibility because it involves personal history and even personality traits. A person can be credible but lack character, or vice versa. For example, in politics, sometimes the most experienced candidates—those who might be the most credible candidates—fail to win elections because voters do not accept their character. Politicians take pains to shape their character as leaders who have the interests of the voters at heart. The candidate who successfully proves to the voters (the audience) that they have the type of character that the voters can trust is more likely to win.

Thus, ethos comes down to trust. How can the author get the audience to trust them so that they will accept their argument? How can the author make themself appear as a credible speaker who embodies the character traits that the audience values?

In building ethical appeals, we see authors

- Referring either directly or indirectly to the values that matter to the intended audience (so that the audience will trust the speaker)

- Using language, phrasing, imagery, or other writing styles common to people who hold those values, thereby “talking the talk” of people with those values (again, so that the audience is inclined to trust the speaker)

- Referring to their experience and/or authority with the topic (and therefore demonstrating their credibility)

- Referring to their own character, or making an effort to build their character in the text

When reading, you should always think about the author’s credibility regarding the subject as well as their character. Here is an example of a rhetorical move that connects with ethos: when reading an article about abortion, the author mentions that they have had an abortion. That is an example of an ethical move because the author is creating credibility via anecdotal evidence and first-person narrative. In a rhetorical analysis project, it would be up to you, the analyzer, to point out this move and associate it with a rhetorical strategy.

It’s your turn now. In the box below, consider how ethos is being used in the “Obama for America” TV ad below:

Kairos: Appeal to Right Time, Place, and Words

Kairos, in Greek, means something like “the right moment” or “an opportune time.” Although the classical rhetoricians did not include kairos among the “core” rhetorical appeals, it turns out to be at least as important and serves much the same function in persuasion as the other appeals, so it seems reasonable to treat it as a rhetorical appeal. In the simplest terms, the most carefully crafted message, delivered by the most credible writer, containing the most flawless logic, can fail if it is not delivered at the right time. You will notice that interest in the issue of gun control, for instance, rises and falls, often in relation to how recently we have experienced a national tragedy involving guns. Choosing the “opportune moment” for a gun control argument is tricky: If it is too soon after a national tragedy, the argument might be dismissed as politicizing the event, but if the writer waits too long, interest in the issue might have waned. In short, timing can be tricky.

In building appeals to kairos, we see authors

- Refer to contemporary events to convey urgency or a sense of doom

- Include a call to action that allows readers to understand their actions/responses as meaningfully contributing to the particular moment in time

It’s your turn now. In the box below, consider how kairos is being used in this Moms Demand Action ad:

Attributions

“Murder! (Rhetorically Speaking),” in Writing Spaces: Readings on Writings, Volume 2, Janet Boyd, CC Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 3.0

“What is the Rhetorical Situation?,” “What is Rhetorical Analysis,” “Rhetorical Appeals: Logos, Pathos, and Ethos Defined,” in A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing, Melanie Gagich & Emilie Zickel, CC Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 4.0

“The Right Words, the Right Time, and the Right Place,” in Rhetorical Choices: A Handbook of Classical Rhetoric for Advanced Civilizations, Ty Cronkhite, CC Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 4.0

Works Cited

Burnell, Carol, et al. “Tone, Voice, and Point of View”. The Word on College Reading and Writing, Open Oregon Educational Resources. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/wrd/chapter/tone-voice-and-point-of-view/

Media Attributions

- Rhetorical situation chart