11 Analyzing Discourse Communities

Overview

In this chapter, you will learn how to analyze the discourse communities that you are part of through primary- and secondary-source research. You will learn to identify and explain key characteristics of your discourse community and evaluate both the benefits and potential limitations of its language practices. The goal is to deepen your understanding of how language both reflects and shapes your personal, professional, and academic communities — and how those language norms are productive or problematic (probably both!).

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Create or adapt research questions to help you identify the four key components of a discourse community

- Identify strategies for using primary- and secondary-source research to answer your questions

- Examine how language norms reinforce the values and goals of discourse communities

- Critique the potential limitations or exclusions created by these communication norms

Step 1: Choose Your Focus — Mapping Your Discourse Communities

We are all part of multiple discourse communities: academic, social, professional, and civic. You might have an assignment that specifies which discourse community you should analyze (for example, your academic major, such as history or biology). But you might have more flexibility in deciding which discourse community to focus on. To help you decide, it can be a useful exercise to map the discourse communities you belong to.

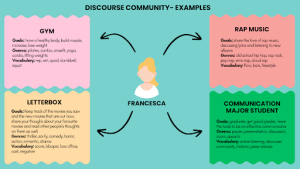

Like a “mind map” or “topic map,” a discourse community map is a visual representation of ideas and their connections. It’s used to organize information in a structured yet flexible way. It typically starts with a central concept or theme, with related subtopics branching out in a networked structure. Use it to map out the primary communities that you belong to. You can use an online mind-mapping or design platform (like Canva [Website]), or simply draw your map on a piece of paper.

Figure 11.1. Francesca’s discourse community map (Francesca_Discourse_Community_Accessible [New Tab])

Once you’ve mapped out your discourse communities, it’s easier to figure out which one is most important to you, or which you think might be most interesting to analyze.

Step 2: What Are You Looking For? — Creating Research Questions

As you embark on your analysis, what should you look for? What questions should you answer? Use the following list as a jumping-off point for identifying the research questions you’ll want to address as you explore your discourse community:

-

Shared Purposes and Goals

- What are the primary goals of this discourse community?

- How do members of the community work toward these goals through communication?

-

Patterns of Language Use and Interpretation

- What specialized vocabulary, jargon, or key terms are commonly used (or are “taboo”)?

- Are there specific writing styles, syntax, or ways of reading that are unique to this community?

-

Shared Genres and Genre Analysis

- Identify the key genres used in your field or community (e.g., research articles, reports, case studies, lab notebooks, or policy briefs).

- Select one specific genre and analyze a few examples of it.

- What are the conventions that make the genre recognizable to insiders?

- How do these conventions reflect the more general communication patterns — as well as the goals and values — of the community?

-

Assumptions and Values

- What values and assumptions shape communication in this field?

- How do these assumptions and values appear in language and writing conventions?

- Who do these communication norms invite in or shut out? How do they erect hierarchies within the field itself?

Step 3: Initial Brainstorm — Capturing What You Already Know

Even without doing any additional research, you probably have some ideas about how to describe each of these aspects of your discourse community. Using what you’ve learned, take 5-10 minutes to revisit the discourse community template from “What Is a Discourse Community?” [Chapter 15] and outline the community you’ve chosen below:

Step 4: How Do You Find Out More? — Using Primary- and Secondary-Source Research Methods

Now that you’ve captured some of the things you already know about your discourse community, it’s time to dig a bit deeper. Check out some of the ways you can use primary- and secondary-source research to answer your key questions.

Secondary Source Research:

- Identify a Controversy. One way to learn more about the communication norms in your chosen discourse community is to start by doing a little secondary-source research to identify a controversy within your field or community. This can help you understand how issues related to communication norms are being challenged from within.

Find the Fight! Examples of Field-Specific Controversies

- “Economics Peer-Review: Problems, Recent Developments, and Reform Proposals” [Website]

- “Researcher’s Perceptions on Publishing ‘Negative’ Results and Open Access” [Website]

- Psychology (and the “social sciences” more generally) is caught between “hard sciences” and humanities, or “soft sciences,” leading to questions about which communication norms and forms of evidence are best (or more authoritative): “What’s the gripe between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ sciences” [Website].

- Political science methodology: Do the methods of modern political science fail to consider the people they impact or the real-world effects of policies? “The Qualitative-Quantitative Distinction in Political Science” [Website].

- Is financial reporting truly “transparent”? Studies suggest that components of the genre of corporate annual reports “embellish the organizations’ actual competitive situation”. “Genre Analysis of Corporate Annual Report Narratives: A Corpus Linguistics–Based Approach” [Website].

- “Museums need to write conversational text to be more inclusive” [Website]

See the chapter “Why Do Professors Talk Like That?” [Chapter 16] for more on controversies about academic language and conventions in specific fields.

Primary-Source Research

- Observations: As a member of this discourse community, you have access to spaces in which you can directly observe members of your community interacting. These can be physical spaces (like a classroom or gym) or virtual spaces (like TikTok or Discord). Just listening to and watching people talk to each other within these spaces can give you clues about implicit communication norms — rules that aren’t written down but are often followed. Pay attention to verbal and non-verbal interactions and displays. For example, if you’re analyzing the field of History as a discourse community, you might notice how professors often summarize student comments during a class discussion rather than letting those comments be interpreted in their original form. Or, if you’re analyzing your favorite soccer team, you might notice how many soccer players wear their hair in elaborate braids. Notice what happens when people follow the implicit rules, and what happens when they don’t (for example, when someone speaks without raising their hand in class). This can also give you clues about how rigid or flexible the written and unwritten rules are in your discourse community.

- Interviews with experts. Conduct an interview with an “expert member” of your discourse community. Your goal is to get information and perspectives that will help you frame your approach to your discourse community analysis. This can help you identify what’s interesting or problematic about your discourse community; it can also help you choose a representative genre and identify genre examples or artifacts (the samples you’ll analyze). You should record your interview or take detailed notes so you have as much material as possible to draw from. You’ll want to use your interview findings to generate ideas for your discourse analysis. You may also choose to pull quotes from this interview to support your findings.

Activity: Interview an Expert (Sample Interview Questions)

Remember to introduce yourself and explain the purpose of the interview. Be sure to consider your question flow and sequencing, and don’t forget to ask follow-up questions!

- What made you interested in joining this field (or community) in the first place?

- What do you see as some of the main objectives or purposes of the field? What are some of the core values of the field?

- What are some of the primary ways or genres that people inside your field use to communicate with one another (e.g., literature reviews, journal articles, or lab reports)? Are there any writing or speaking conventions that are unique to your discipline (e.g., structure, citation style, or level of formality)?

- How did you learn to communicate in these specific ways or genres? Were you taught explicitly or did you pick it up along the way? Was it hard or easy?

- Can you tell me about a time that you “failed” to communicate according to the norms of your field, how you felt, and what you learned from that experience?

- What common mistakes or problems do you see in how students new to the field communicate? What advice would you give them?

- Can you name any specific “good” or “bad” examples of a type of communication (e.g., a summary, lab report, journal article, or blog) in your field?

- Would you change anything about how people in your field communicate with each other, or with people outside that community? Do you think there’s anything about your field’s communication norms that is currently changing?

Further Reading: Want more background on primary-source research methods, like observations, interviews, and surveys? Check out “Introduction to Primary Research: Observations, Surveys, and Interviews” [Online PDF] by Dana Lynna Driscoll.

- Genre Analysis: Genre, in the rhetorical sense, refers to a “typified mode of communication that responds to a recurring rhetorical situation” (Miller 23). For example, think of lectures, slide presentations, or peer-reviewed journals. Deep-diving into a specific genre that’s important to your community or field can tell you a lot about its communication norms and practices (and, by extension, its values and assumptions). You can read more about genre analysis in “Analyzing Genres” [Chapter 21].

Example: #EconomicsSoWhite (and Male)?

Imagine you are analyzing the field of economics as your discourse community. As part of that analysis, you’re exploring the genre of academic journal articles published in economics-specific journals, like The Quarterly Journal of Economics (QJE) and the American Economic Review (AER).

Here are two of your samples:

You notice that this genre exhibits the following style and substance features:

- Lots of community-specific terminology, or “jargon”

- Extensive use of mathematical equations

- Extremely formal tone (no emotional or personal language)

You know that there are controversies in your field concerning who is primarily involved in economics, as well as who has the most influence or prestige: “Why is Economics Still Largely a White Male Preserve?” [Website]

You create a hypothesis connecting the genre elements with who is typically included or excluded from this field: is it possible that the formality, lack of personal voice, and advanced level of math of academic journal articles in the field encourage white men to enter the field, and tend to exclude or discourage women and people of color from doing so?

This could be the central research question of your discourse community analysis, which your combined primary- and secondary-source research could confirm or challenge (or note that further research is needed).

Step 5: Analysis and Synthesis — Putting It All Together

Now that you’ve gathered your data, you’ll need to put it all together — moving from analysis to synthesis. Your goal should be to both identify and critique the communication norms in your discourse community. Return to Step 2 and your research questions. What patterns do you notice when you review your answers? How do the communication norms reflect — or undermine — the values and goals of your community? How could they be changed to be more effective — or more ethical and inclusive?

To guide your synthesis, consider the following questions:

- What do participants have to know or believe to understand or be considered members of the discourse community?

- Who is invited into the discourse community, and who is excluded?

- What roles for writers and readers (or creators and audiences) does it encourage or discourage? What values, beliefs, goals, and assumptions are revealed through the patterns of language use?

- What “language ideology” [Chapter 15] does your discourse community share, either implicitly or explicitly?

- What actions or outcomes do these communication norms help make possible? What actions or outcomes do they make difficult?

- What attitude toward the public or “outside” audiences is implied by the communication norms of the discourse community?

Student Examples

Sample Assignment: “What Does ‘Good Communication’ Look Like in Your Major?”

Logistics:

- 6-8 minute presentation (extend by 2-3 mins per partner, with no more than three people presenting)

- Slide deck required (submitted on Canvas)

- Cite your “expert” interview

- Cite at least one class text

- Cite at least two examples of your chosen genre for the genre analysis section

Format:

- Intro: This is where you get the audience’s attention and create anticipation around the rest of your presentation.

- Show, rather than tell, by starting with something small that represents the larger topic. Tease the strands, themes, and terms that will be important throughout. Consider narratives, history, current events, statistics, and quotes. These can all be useful for creating audience anticipation.

- Establish your credibility — briefly state your relation to the topic and why you care. Your audience will want to understand your character and competence level.

- Introduce the topic, contextualize it, and explain why it’s relevant for your audience. Present your claim (that something about language usage in your discourse community is productive, problematic, or both) and let your audience know why they should care.

- Body: Your presentation should accurately describe and analyze the key characteristics of your discourse community. Consider the following questions when writing:

- What are the shared purposes and goals of the community?

- What are the most common patterns of language use and interpretation in the community?

- What genres of communication do community members use? Be sure to include some genre analysis.

- Conclusion: Here is where you offer a critical perspective, connecting the language norms of your discourse community with underlying assumptions and values.

- In what ways do these communication norms reinforce the community’s goals and values?

- In what ways might they be exclusionary, restrictive, or even contradictory to the stated goals of the field? Consider accessibility, diversity, and adaptability of communication within the discourse community.

- What now? Do you have any recommendations for how you think the field should change its language norms?

Works Cited

Borrillo, Lana. “History Discourse Community Analysis.” Major Discourse Community Analysis Presentation, HONC 132: Rhetorical Communities, University of San Francisco, 20 Mar. 2025.

Devitt, Amy J. Writing Genres. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn. “Introduction to Primary Research: Observations, Surveys, and Interviews.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, vol. 2, edited by Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky, Parlor Press, 2011, pp. 153–174.

Echevarría, Lucía et al. “Researcher’s Perceptions on Publishing ‘Negative’ Results and Open Access.” Nucleic Acid Therapeutics, vol. 31, no. 3, June 2021, pp. 185–189, doi:10.1089/nat.2020.0865.

Freedman, Jan. “Museums Need to Write Conversational Text to Be More Inclusive.” Museums + Heritage Advisor, 29 Oct. 2018, www.museumsandheritage.com/advisor/insights/museums-need-write-conversational-text-inclusive/. Accessed 15 July 2025.

Hicks, Sadie, and Sophia Kinninger. “Psychology Discourse Community Analysis.” Major Discourse Community Analysis Presentation, HONC 132: Rhetorical Communities, University of San Francisco, 20 Mar. 2025.

Miller, Carolyn R. “Genre as Social Action.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 70, no. 2, 1984, pp. 151–67.

Rutherford, Brian A. “Genre Analysis of Corporate Annual Report Narratives: A Corpus Linguistics–Based Approach.” Journal of Business Communication, vol. 42, no. 4, 2005, pp. 349–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943605279244.

Siemroth, Christoph. “Economics Peer-Review: Problems, Recent Developments, and Reform Proposals.” The American Economist, vol. 69, no. 2, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1177/0569434524126948.

Swales, John M. “The Concept of Discourse Community.” Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings, Cambridge University Press, 1990, pp. 21–32.

Sylvan, David J. “The Qualitative-Quantitative Distinction in Political Science.” Poetics Today, vol. 12, no. 2, Summer 1991, pp. 267–286. Duke University Press.

“What’s the Gripe Between ‘Hard’ and ‘Soft’ Sciences? The Debate Rages On.” Utah State University Today, 11 June 2004, Utah State University, www.usu.edu/today/story/whats-the-gripe-between-hard-and-soft-sciences-the-debate-rages-on. Accessed 15 July 2025.

Attributions

This chapter was written by Leigh Meredith.

Media Attributions

- Francesca_DiscourseCommunity © Francesca Cassacia, using Canva is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- EconomicsDiscourseCommunity