14 Analyzing Genres

Overview

As discussed in the “What Is Genre?” [Chapter 15] chapter, genre can be defined as a set of communication strategies for addressing a recurring rhetorical situation [Chapter 2]. When we analyze genre, then, we can think of ourselves as detectives, attempting to discover the conditions and motivations that led people to invent these strategies in the first place. This process can help us understand genres from the inside out — so that we see them not merely as confusing sets of rules, but as answers to questions or solutions to problems. Analysis can also empower us to challenge genre norms and critically evaluate whether a given strategy makes sense for our specific communication tasks and discourse communities [Chapter 12].

The following chapter provides guidelines for analyzing genres — from choosing a genre to identifying its components to critically evaluating its effects.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Apply rhetorical methods to evaluate the effectiveness of different genres in conveying messages to specific audiences

- Connect the concept of genre to the norms and values of specific discourse communities

- Critically assess the degree to which genre conventions challenge or reproduce inequities and exclusions

- Design suggestions for creating or modifying genres to address emerging communication needs, inequities, and exclusions

Step 1: Choosing A Genre

Genres are all around us — so you have a lot to choose from! When deciding what to analyze, consider the following:

- What genre(s) have you been asked to use in a given class or job? Genre analysis can help you better understand the ways you are expected to write, speak, or otherwise communicate in an academic or professional context.

- What discourse communities are you a part of (at school, at work, or in your free time)? Analyzing a genre common to your community can better help you reflect on your membership in — or relationship to — that community.

- We’ll discuss this more below, but you should choose a genre that reveals something interesting and unexpected — either about the discourse communities that use it or its consequences (negative or positive). Your analysis should be more than a list of features — it should uncover something that you or your audience might not have been aware of before.

- Take your time — read through the questions and suggestions below to help inform your selection, rather than rushing into a choice.

Reflection

Imagine that you’ve been assigned to give a class presentation, followed by a question and answer session (Q&A). Are these two parts of the assignment part of the same genre or different genres? Why?

Step 2: Gathering Representative Examples and Secondary-Source Research

First, you’ll need to gather examples of your genre.

- Start with the easy-to-find stuff: If you’re studying a fairly public genre — like journal articles — you can usually find lots of examples in online databases like JSTOR or Google Scholar.

- Ask the experts: If you’re stuck, reach out to someone who uses your chosen genre regularly (like a nurse, professor, or business manager) and ask if they can point you to sample materials.

- Aim for 3–4 examples: One example isn’t enough to see patterns — you want several so you can get a sense of what’s typical and what’s unique.

- Compare to the “standard” version: Once you have your samples, try comparing them to the genre’s typical form — this can help you spot where they follow or break the expected rules.

- Do some background digging: Check whether your genre has already been studied. For example, formats like IMRaD [Website] (for scientific papers) or literature reviews have been analyzed before — use this prior work to strengthen your own analysis.

Need something more behind-the-scenes? For more private genres (like patient medical history forms [Website]), you might need to ask your professor for help or find creative ways to access samples — just be sure to respect privacy and ethics!

Step 3: What Are You Looking For? — Creating Research Questions

Use your samples to identify the following components of your genre:

- Style: What’s the form and structure of the text? What patterns do you notice in terms of tone, formality, syntax, imagery, organization, etc.?

- Substance: What’s it about? What aspects are discussed or represented? What counts as “evidence” (e.g., datasets or personal experience)? What rhetorical appeals (ethos, pathos, or logos) are most prevalent?

- Situation: Who are the authors and audiences for this genre? What discourse community uses this genre? What’s the exigence (recurring need or problem) the genre is responding to?

- Social function: What is it directing the audience to think or do in response to the situation? How is it reflecting or reinforcing the values, priorities, and expectations of the community in which it’s embedded? This is ultimately what you’re trying to find out through your analysis!

In other words, you’re trying to identify “rules” or conventions (implicit or explicit) in a genre’s style and structure, and then analyze their significance — why is this interesting or useful? If you’re analyzing a genre in connection with a discourse community, try to imagine how the format solves problems or reflects beliefs or assumptions held by that community. Try your best to see these genres as “strange” — what’s missing? What could be different? Notice everything and take nothing for granted!

Activity: “Trash Talk” or “Smack Talk”?

In this clip from the hit TV show The Office (<1 min), character Kelly Kapoor distinguishes between “trash talk” and “smack talk.”

Can you identify features of “style” and “substance” in her explanation of the differences between these two forms of insult? Do you think they perform the same “social function,” or do they have different effects or impacts on the listener?

Below, you can find additional explanation and guidance for each of the basic categories you should identify and analyze. These guidelines are adapted from those developed by Anis Bawarshi, English professor and Director of Composition at the University of Washington (159).

Style

This mostly involves elements of structure, form, and tone. Most genres have a specific structure. For example:

- General to specific (e.g., encyclopedia articles or introductions to research papers)

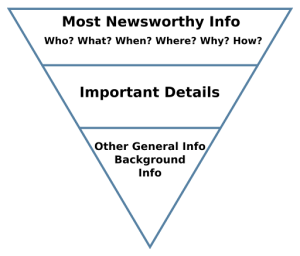

- Specific to general (the “inverted pyramid” structure of a news article)

Figure 14.3. The “inverted pyramid” structure of breaking news articles [Image Description]

Be sure to consider other organizational elements:

- Are they long or short?

- What are their parts, and how are they organized?

In addition to structure, consider stylistic elements:

- In what medium (“Media Matters” [Chapter 6]) are texts of this genre presented? How does the medium shape the genre?

- What do you notice about the aesthetics or visual language? What fonts or organizational structures are used? Are there images, graphics, or charts? Is there anything notable about the visual style?

- What types of sentences do texts in the genre typically use? How long are they? Are they simple or complex, passive or active?

- What vocabulary is most common? Is jargon used? Is slang used?

- How would you describe the writer’s voice? Is it monologic (just one author speaking) or dialogic (like a conversation)? Is it formal or informal? What perspective does the writer choose (e.g., first person or third person)?

Substance

Substance refers to the content and topics of the genre. Consider the following:

- What content is typically included? What is excluded?

- What issues, ideas, and questions does the genre address?

- What sorts of examples are used?

- What counts as evidence (personal testimony, facts, etc.)?

- What rhetorical appeals are used? What appeals to logos, pathos, and ethos appear?

Situation

Use the following questions to analyze “The Rhetorical Situation” [Chapter 2] of the genre:

- Context: Where does the genre appear? What medium is typically used (e.g., written, spoken, or visual)? With what other genres does this genre interact (e.g., lectures and lecture notes)?

- Authors/rhetors: Who writes or creates the texts in this genre? Are multiple authors/creators possible? How do we know who the creators are? What knowledge, experience, or education do creators or authors need? In what conditions do authors compose content (e.g., in teams or individually; on paper or digitally; slowly or in a rush)?

- Audiences: Who reads or receives the texts in this genre? Is there more than one type of audience for this genre? What knowledge, experience, or education do authors need? In what conditions do audiences receive the message (e.g., at work, in their free time, or at school)?

- Exigence: Why is the genre used? What purpose(s) does it fulfill for the people who use it?

Social Action

What effect does this type of text have on its creators and audiences? How does it shape or impact them, whether intentionally or unintentionally? Consider the following:

- What does someone need to know or believe to really “get” this type of writing?

- Who is this writing for? Who is it not for?

- What does this genre expect from the writer and the reader? Does it invite some people to participate and leave others out?

- What kinds of values, beliefs, or assumptions show up in the way this writing is done?

- What ideas about language does this genre seem to reflect? For example, does it suggest that writing should be formal, objective, emotional, personal, etc.?

- How does it treat the subject matter? What topics or details does it focus on, and what does it leave out?

- What kinds of feelings does it evoke in people? What actions or responses does it make easier or harder for people to take?

- What kind of attitude does the writing show toward its audience? What kind of worldview does it seem to represent?

Activity: Famous Last Words — Analyzing the Eulogy

Have you ever been to a funeral, or seen one on TV or in a movie? If so, you’re probably familiar with the genre of the “eulogy” [Website] — a speech in honor of the deceased. Imagine that you want to use eulogies for your genre analysis.

First, you’d want to watch some examples of eulogies. For example, check out actress and media personality Oprah Winfrey’s eulogy for civil rights activist, Rosa Parks (~4 mins).

Based on this, along with any relevant personal experience, list some characteristics of the eulogy in the following categories, expanding on the following:

- Style: The speech is usually formal, highly structured, and somber.

- Substance: The speaker introduces their relationship to the deceased, shares personal stories, compliments the deceased’s good qualities, and ends with a message of hope for the future.

- Situation: Eulogies are generally presented at funerals to an audience of friends and family of the deceased.

Then, consider what you think the “social action” of the eulogy might be. In other words, why does this genre exist? What is its intended purpose? What “problem” does it solve? What impact or effect on the audience (and the speaker) is it supposed to have? How do the style and substance elements help achieve that purpose?

Now, watch comedian and actor John Cleese’s eulogy for Graham Chapman (~2 mins), who was a fellow actor in the “Monty Python” [Website] comedy troupe. How does Cleese’s eulogy both fulfill and subvert expectations for the genre? How is the “social action” (the impact on the audience) similar to or different from that of Oprah’s eulogy for Rosa Parks? What does Cleese’s alteration of the genre, and the response of his audience, tell us about the values and norms of his discourse community?

Example: Genre Analysis Essays

Check out these examples of genre analyses, written by undergraduate students, and published in Young Scholars in Writing [Website], a journal that publishes undergraduate research in rhetoric and writing:

As you read, note how these authors use detailed evidence about the “style” and “substance” of the genres they analyze to make arguments about their “social action” (how effective they are, why they vary, and how they fill in the gaps of other genres).

Step 4: Connecting Genre to Discourse Community

One way to uncover the deeper significance of a genre is to identify how that genre might reflect and reproduce the norms and values of a discourse community. For example, if you watched actor John Cleese’s eulogy above, you probably noticed how humor and challenging “good taste” were important values in Cleese’s particular discourse community. The way in which Cleese manipulated and subverted the genre — the way he challenged genre norms — helps us understand something about his discourse community’s assumptions and values (which would not necessarily be shared outside that community).

Notice, too, that finding examples that challenge typical genre norms can be a great way of both identifying those norms and of figuring out whether they might be problematic or exclusionary.

Activity: Analyzing an Outlier — What Can Issa Rae Teach Us About the Genre of Acceptance Speeches?

If you’ve watched any awards shows, like the Oscars, the Grammys, or the Golden Globes, you probably have some idea of the typical characteristics of an awards acceptance speech.

With those characteristics in mind, check out actress and writer Issa Rae’s acceptance speech for the “Emerging Entrepreneur” award at the 2019 Women in Film Annual Gala (~3 mins).

As you watch, consider the following:

- How is Rae fulfilling expectations for the genre?

- How is she frustrating or challenging expectations?

- What connection could Issa Rae’s speech have to her own discourse community, and how might those norms be different from those of “the public”?

- What does her speech suggest about the genre of the awards speech as a whole? About the relationship of gender (and perhaps race) to the typical style and substance of the awards speech? Does her version have any impact on the overall “social action” of the speech or its impact on the audience?

Step 5: Additional Tools and Approaches for Genre Analysis

Feeling stuck? The following section explains a few approaches that might help you uncover the “social action” of your genre — in terms of its problems, the values and assumptions it reflects, and its impact on its users. These strategies are especially helpful if you’ve answered some of the questions above, but are still a bit confused about the topic of genre.

These approaches are:

- Parody

- History

- Generative AI

Parody

Parody is an art form that exaggerates the common features of a genre to the point of absurdity — you can think of parody as a kind of “meta-genre,” in the sense that it takes genre itself as its subject. Finding a parody of your genre can be a great way to identify the hidden features of your genre, precisely because parody works through taking something small and exaggerating it so that it becomes funny — and more recognizable. This exaggeration can make subtle features more obvious and reveal patterns that were previously hidden from you. By amplifying a genre’s typical messages, parody often critiques the values or assumptions the genre promotes. This kind of critique helps us understand the genre’s role within a larger discourse community — what it encourages people to think, feel, or do.

Example Parody Analysis: “Honest Political Ads”

Watch the following video, a parody of a political campaign ad (~2 mins):

What elements of “style” and “substance” that are typical in a political campaign ad are being exaggerated here? What do they reveal about the genre, how it persuades its audience, and what some of its problems might be?

For example, you might notice the following:

- Style: The parody exaggerates the emotional music, repetitive slogans, and “everyday life” visuals, showing how style is used in campaign ads to manipulate feelings rather than communicate detailed information.

- Substance: It mocks the vague promises and attacks, revealing how little substance many campaign ads offer — and how they rely on identity, fear, or pride more than logic or policy.

- Social Action: It shows that political ads are often not designed to be informative. Instead, they are crafted to shape identity, influence behavior, and fit into the values of a political discourse community. Further, it suggests that political ads are manipulative and misrepresent the actual commitments of politicians, which are to funders and special interests rather than to the public at large.

Example Parody Analysis: “Chicken Chicken Chicken”

They might be harder to find, but parodies of academic genres work similarly. Watch how Doug Zongker’s “Chicken Chicken Chicken” parody (~4 mins) of an academic presentation at a psychology conference makes the entire audience erupt into laughter. It might not be as funny to all of us non-psychology majors, but the humor derives from how it utilizes all of the stylistic conventions of presentation without actually presenting any content.

By exaggerating these features, the parody lays bare the genre’s unwritten rules regarding what counts as valid knowledge, how credibility is constructed, and how meaning is made. It prompts us to ask ourselves whether formal structures are used to promote clarity or mask emptiness, and whether jargon sometimes amounts to little more than signaling membership in a discourse community.

History and Genre Evolution

Genres don’t emerge out of thin air. They evolve and transform as needs and norms change. For example, consider the “IMRaD” [Website] structure for journal articles, which is now ubiquitous in the sciences and social sciences. It may seem like it’s been around forever — and that it’s the only way in which scientific information could possibly be communicated. But, according to research done by Luciana Sollaci and Mauricio G. Pereira, it’s really only been in use since the 1940s, and only became “standardized” in the 1970s (Sollaci and Pereira). Previously, scientists commonly communicated discoveries primarily through letters.

(Genre Evolution_Accessible [New Tab)]

Further, new genres often borrow from older genres. For example, did you know that the contemporary genre of food recipes (with a list of ingredients at the top, and step-by-step instructions below) originally evolved from recipes for homemade medicines? In fact, in the 17th and 18th centuries, there wasn’t a clear distinction between recipes for medicines and recipes for food — in fact, recipe books often contained a mixture of both (The Great History Bake Off: Baking and Medicine in Early Modern Recipe Books). But the genre also evolved over time; originally, recipes looked more like paragraphs than lists.

(Recipe_Genre_Evolution_Accessible [New Tab])

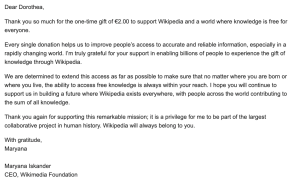

Finally, consider how the genre of email took on many of the structural components of analog letter-writing (from the “Dear X” at the top of the email to the formal sign-off at the bottom).

Figure 14.4. Example of an email with many of the genre features of a traditional handwritten letter (Wikimedia_Thank_You_Letter_Transcript [New Tab])

Researching a little bit about the history of your genre, like when and where it was first used, and what kinds of genres it might have borrowed from, can help you understand your genre better. It shows us that genres aren’t fixed — they grow, shift, and respond to the needs of the people who use them. Genre scholars like Risa Applegarth have pointed out that genre change is often the result of power and politics. In her analysis of the monograph genre in anthropology, she shows how the genre’s change from “flexible, variable, and capacious to more rigorously bounded and policed” helped the discipline “gatekeep” itself in a quest to become more “professional” and “scientific” (457). As this shows, when we study how a genre has changed or where its parts come from, we get a clearer picture of why it looks and sounds the way it does today — and who has benefited or lost out along the way.

Generative AI

You probably know that one of the problems with using generative AI or large language models (LLMs), like ChatGPT, is that they tend to produce bland or clichéd writing. While this is usually a downside of generative AI, it can actually be a benefit when it comes to genre analysis. That’s because generative AI can produce “typical” examples of a genre, giving you a standard or template to analyze.

It can also even help with the analysis itself, in some of the following ways:

AI is really good at spotting repeated features across many examples. If you’re studying a genre like job ads or research articles, it can help identify:

- Common sentence structures

- Frequently used phrases or jargon

- Typical organization (e.g., introduction → background → methods)

It can also help you compare across genres in order to understand what makes your genre unique, or what it shares with similar genres. Let’s say you want to understand how a press release differs from a news article or a blog post on the same topic. AI can:

- Compare tone, style, and structure

- Highlight differences in purpose or audience

- Show how each genre handles the same content in different ways

If you’re curious about genre evolution, like how academic writing has changed from the 1800s to today, it can:

- Pull historical examples

- Summarize how tone, structure, or values have shifted

- Explain what social or cultural factors may have caused those changes

Generative AI doesn’t replace human thinking — but it can help you notice more, ask questions, and test ideas more quickly. Genre analysis is ultimately about understanding how people communicate — and AI can help make those patterns visible and meaningful.

Activity: Magic + Technology: Using Generative AI to Analyze the Genre of “Spells”

In this assignment from Dana LeTriece Calhoun of the University of Pittsburgh, students use a large language model (LLM) like ChatGPT to create and analyze the genre of “spells.” Check it out here: “Spellcraft & Translation: Conjuring with AI” [Website]

Step 6: Putting It All Together

Check out the section below to see an example of genre analysis by a USF student. It was originally part of an oral presentation — if you want more context, you can check out the accompanying slides, which lay out the presenter’s argument. The author uses genre analysis to identify what’s effective — and ineffective — about typical climate change documentaries. Notice how the author uses an “atypical” representation (an example that challenges accepted practices) to highlight what works — and what doesn’t — about the genre’s norms. Further, she uses this comparison to advocate for how these genre norms should change to be more effective and inclusive.

Example: Violet Robinson, “What’s the Matter with Climate Change Documentaries?”

Activity: Using the Genre Analysis Matrix

Use the “Genre Feature Analysis Matrix” [Online PDF], developed by Jennifer Fletcher, professor of English at California State University. It’s designed to help you capture and identify key genre features from your examples or “mentor texts” (features like medium, language choice, rhetorical devices, etc.). Specific fields might help prompt you to see elements and patterns you wouldn’t have otherwise noticed.

Sample Assignment: Genre Analysis Presentation

Overview and Purpose

In this oral presentation, you’ll deliver an analysis of a genre of your choice. Your aim is to make an argument about the genre’s “social action.” In other words, how does it shape the way writers and readers respond to a particular rhetorical situation? What is it trying to do — and is it effective at achieving that aim? Who does it include or exclude? How does it reflect the values, priorities, and assumptions of specific discourse communities?

You will be doing a “close reading” of the genre conventions in the examples you choose. You’re not (primarily) looking for other outside texts to explain your artifacts, although you’ll want to do some outside research to contextualize your analysis and build on what others have written about your genre — this helps establish the stakes for your piece and the space in the conversation that you’re addressing. Since you’ll be performing rhetorical analysis on your artifacts, your main goal is to pay close attention to your texts, observing them carefully for the strands, binaries, and anomalies that recur and seem most interesting, strange, or revealing.

Presentation Structure

Basic Guidelines

- Length: 8-10 minutes

- Format: Must include a visual aid (to submit and use in class)

Required Sections

- Introduction: an intro that grabs the audience’s attention; identifies the genre you will be analyzing; states your research question or thesis; and hints at why it all matters (why should the audience care?)

- Genre analysis:

- A brief description of the context in which these genre conventions occur (e.g., the situation they’re responding to and the community that uses them)

- Analyze the genre rhetorically, explaining the most meaningful patterns of substance and style. Provide concrete evidence (e.g., direct quotes or screenshots) from your artifacts to support your claims.

- Don’t describe the whole artifact; only discuss the points relevant to your analysis.

- Interpret what these genre features mean — what are the larger implications of the rhetorical choices in these artifacts? What’s the ultimate “social action”? How do these artifacts/genres impact audiences, constrain or shape ideologies, and impede or enable certain voices or experiences?

- Conclusion: Your conclusion should summarize the main points of the presentation and, crucially, indicate the importance or stakes of your analysis.

Be sure to expand on the significance of the “social action” — the reason why this topic matters. Why is it important for your audience to know this? What should they do about it?

Further Reading and Resources

- Writing in Genres: A Guide to Composing Academic and Professional Texts

- “Bad Ideas about Genre”

- “Make Your ‘Move’: Writing in Genres”

- “Genre Production Courses and Materials”

- “Writing the Genres of the Web”

- For further guidance on what features to look for in analyzing a genre, check out the chapter on identifying “COLDV” (content, organization, language, design, and values).

Works Cited

Ahmed, Maryam. “Legal Genres: The Gravity of the Supreme Court Opinion.” Young Scholars in Writing, vol. 17, 31 Jan. 2020, pp. 137–146. https://youngscholarsinwriting.org/index.php/ysiw/article/view/307.

Applegarth, Risa. “Rhetorical Scarcity: Spatial and Economic Inflections on Genre Change.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 63, no. 3, Feb. 2012, pp. 453–483. National Council of Teachers of English, www.jstor.org/stable/23131597.

Ball, Cheryl E., and Drew M. Loewe, editors. “Bad Ideas about Genre.” Bad Ideas about Writing, West Virginia University Libraries, 2017, https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/bad-ideas-about-writing.

Bartlett, Chelsey. “When Writing Cuts Deep: The Rhetoric of Surgical Short Stories.” Young Scholars in Writing, vol. 9, 2015, pp. 106–116. https://youngscholarsinwriting.org/index.php/ysiw/article/view/133.

Bawarshi, Anis S., Genre and the Invention of the Writer: Reconsidering the Place of Invention in Composition, Utah State University Press, 2003.

Calhoun, Dana LeTriece. “Spellcraft & Translation: Conjuring with AI.” The WAC Clearinghouse, Colorado State University, https://wac.colostate.edu/repository/collections/textgened/creative-explorations/spellcraft-translation-conjuring-with-ai/.

Cara. “Writing the Genres of the Web.” Writing for Digital Media, PALNI Pressbooks, https://pressbooks.palni.org/writingfordigitalmedia/chapter/writing-the-genres-of-the-web/.

Dawe-Woodings, Ginny. “The Great History Bake Off: Baking and Medicine in Early Modern Recipe Books.” Royal College of Surgeons of England, 21 Oct. 2016, https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/library/blog/great-history-bake-off/.

Devitt, Amy J. “Teaching Critical Genre Awareness.” Genre in a Changing World, edited by Charles Bazerman, Adair Bonini, and Débora Figueiredo, WAC Clearinghouse and Parlor Press, 2009, pp. 337–351

Devitt, Amy J. Writing Genres. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004.

“Eulogy.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, last modified [approx. Mar. 2025], en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eulogy.

Fletcher, Jennifer. “Genre Feature Analysis Matrix.” Teaching Literature Rhetorically: Transferable Literacy Skills for 21st Century Students, Stenhouse Publishers, 2018, pp. 266–267. Rhetorical Thinking, https://rhetoricalthinking.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/genre-feature-analysis-matrix-1.pdf.

Frame, Stephanie. Writing in Genres: A Guide to Composing Academic and Professional Texts. California State University Pressbooks, 2023, https://pressbooks.calstate.edu/navigating/.

Genre Across Borders (GXB). “Genre Production Courses and Materials.” Genre Across Borders (GXB), https://genreacrossborders.org/pedagogy/genre-production-courses.

“Graham Chapman’s Eulogy by John Cleese.” YouTube, uploaded by jester0000, Mar. 2006 (approx.), https://youtu.be/CkxCHybM6Ek.

“Honest Political Ads – Gil Fulbright for Senate.” YouTube, uploaded by RepresentUs, 2014, https://youtu.be/wz_V4lRdtjo.

“IMRAD.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 10 July 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IMRAD.

“Issa Rae Receives the Emerging Entrepreneur Award at the 2019 Women In Film Annual Gala.” YouTube, uploaded by Women In Film, 2019, https://youtu.be/Db1dPZ5abn4.

Jacobson, Brad, et al. “Make Your ‘Move’: Writing in Genres.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, vol. 4, Parlor Press, 2021, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/writingspaces4/jacobson.pdf.

“Kelly Talks Smack.”The Office clip, uploaded by Zilchy2k, Sept. 2013, YouTube, https://youtu.be/Jh2Kwe2ZIFk.

“Monty Python.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, last modified 13 July 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python.

“New Patient Medical History Form.” University of North Carolina Physicians Network, n.d. PDF file, www.uncpn.com/app/files/public/664e1f36‑c9bf‑4f5f‑a03d‑93f7ced2b564/uncpn‑form‑new‑patient‑medical‑history.pdf. Accessed 15 July 2025.

“Oprah Winfrey’s Heartfelt Eulogy for Rosa Parks.” YouTube, uploaded by Voices Through History, 1 Mar. 2024, https://youtu.be/BOhmQW_RaoQ.

Pantelides, Kate L., et al., editors. The Ask: A More Beautiful Question, 2nd ed., Middle Tennessee State University Press, 16 Aug. 2021. “Analyzing the Genre of Your Readings.” ENGL 1020: Research & Argumentative Writing, digital resource, mtsu.pressbooks.pub/engl1020/chapter/genrereadings/.

Robinson, Violet. “Climate Change Documentaries: A Genre of Scientific Communication.” Genre Analysis Presentation, HONC 132: Rhetorical Communities, University of San Francisco, 26 Oct. 2021.

Sollaci, Luciana B, and Mauricio G Pereira. “The introduction, methods, results, and discussion (IMRAD) structure: a fifty-year survey.” Journal of the Medical Library Association. vol. 92,3 (2004): 364-7.

Zhu, Huisheng and Qinyan Cai. “Flexible Intimacies in Three Moves: A Genre Analysis of the Scholarly Book Preface.” Young Scholars in Writing, vol. 17, 2020, pp. 147–160. https://youngscholarsinwriting.org/index.php/ysiw/article/view/308.

Zongker, Doug. “Chicken Chicken Chicken.” YouTube, uploaded by Yoram Bauman, 16 Feb. 2007, https://youtu.be/yL_-1d9OSdk.

Image Descriptions

Figure 14.4. A simple graphic of an upside-down triangle with a blue outline and two evenly spaced horizontal lines inside, creating three stacked bands. The point faces downward and the background is plain/white. This shape is often used to illustrate an inverted pyramid or tiered hierarchy. The first stacked band states “Most Newsworthy Info: Who? What? When? Where? Why? How?”. The second stacked band states “Important Details”. The third stacked band states “Other General Info, Background Info”. [Return to Figure 14.3]

Attributions

This chapter was written by Leigh Meredith.

Media Attributions

- KindsofGenres © Leigh Meredith, with ChatGPT is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- pexels-henri-mathieu-8348624 © Henri Mathieu-Saint-Laurent

- InvertedTriangle © The Air Force Departmental Publishing Office (AFDPO) / derivative work: Makeemlighter is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Thank-you-email © Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- magicwand © RDNE Stock project is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license