20 Ethical Issues for Generative AI and Communication

Overview

Generative AI and Large Language Models (LLMs) are impacting almost every sector of business and education. Because of this, we need to be mindful of how our use of these technologies impacts the world around us. In other words, the rhetorical situation for using something like ChatGPT isn’t just between you and your audience.

We should also consider who created this technology and who uses it (modifying the rhetor’s position in the rhetorical situation); how people receive this technology (modifying the audience’s position in the rhetorical situation); and what effects this technology has on the world (modifying the message and context of the rhetorical situation).

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Review and update your understanding of the rhetorical situation to account for generative AI’s impacts on communication

- Compare and contrast the benefits and drawbacks of AI usage in terms of effectiveness and ethics

- Recognize the ways that generative AI reinforces language ideologies

- Evaluate the usefulness of generative AI tools for source evaluation and research

The Rhetorical Situation

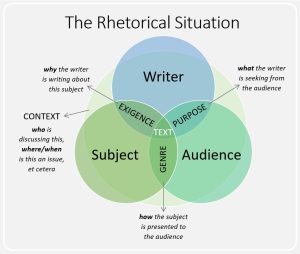

If you need a refresher, you can review “The Rhetorical Situation” [Chapter], which describes the dynamic interaction between the communicator, audience, message, and context. These elements shape how a message is crafted and interpreted. Below, we’ll cover how using Generative AI as a communication tool can impact each element of the rhetorical situation, and raise ethical issues related to these impacts.

Figure 20.1. The Rhetorical Situation infographic. (Rhetorical_Situation_Accessible Infographic [New Tab])

Rhetors

Normally, “rhetor” is a general stand-in term for the writer, speaker, or creator of a text. In contemporary media production, we might broaden that out to include all of the people who contributed to a project — in a film, for example, the rhetor might include not just the director but also the actors, scriptwriter, cinematographer, composer, costume designer, and anyone else whose collaboration made the movie possible. In digital and social media contexts, the rhetor might be not just the influencer but also the company that is sponsoring their post — or not just the podcaster but also the media company that produces their podcast.

In the context of generative AI, we can think of the role of “rhetor” in two distinct ways:

- The collaboration between humans and generative AI technology

- The companies behind generative AI technologies

Humans and Generative AI as Collaborative Rhetors

The rhetor is not just the person inputting a prompt. For example, consider the example of a human composing text with AI assistance. Even though the human is directing the input, the LLM itself might be considered a co-rhetor — not because it has intelligence or agency (remember, it doesn’t!; see “Generative AI and Language” [Chapter] for more about this), but because the output of an LLM is not totally within the writer’s control. The use of generative AI influences the way that we communicate, so it makes sense to think of the technology not just as a tool but also as part of the rhetorical situation.

Users can request that ChatGPT respond in a particular style of writing, like the linked Harry Potter example in the previous chapter illustrates. But unless that is specified, LLM’s predictive text generation algorithm will produce text that is stylistically similar to the corpus of writing that it was trained on. This has a couple of implications. Firstly, ChatGPT’s default “voice” has a certain distinctive style to it. Its tone tends to be a little more formal than the way most people write, while also attempting to be polite and helpful, as discussed below. But more specifically, this tone (formal, polite, and helpful) appears this way to us because it uses language in a way that is associated with dominant modes of expression. As we discussed in another chapter, there are multiple forms of “English” that can be influenced by a communicator’s gender, race, socioeconomic class, level of education, cultural background, and more. However, LLMs produce writing in a way that aligns with Standard American English, reinforcing this mode of English as “correct.” The article “ChatGPT Threatens Language Diversity” [Website] explains this issue, as well as how language diversity has been threatened in global and historical contexts (Bjork).

The way that we use language to write and speak is connected to who we are and how we experience the world. An LLM’s output probably doesn’t sound like how you would choose to express yourself, so its ability to represent your ideas is severely limited.

Recently, many users have also noticed that chatbots are highly sycophantic — that is, they tell the user what the user wants to hear. They are not a real substitute for brainstorming or testing out ideas with another person, because they are intended to be agreeable and supportive in what the user is trying to accomplish. As a result, our thinking might not be improved by consulting a chatbot because it will tend to reinforce what we already think, rather than challenge inaccurate views or offer meaningful feedback. One writer discovered this when she asked ChatGPT for help compiling a portfolio to send to potential agents; you can see from her “Diabolus Ex Machina” transcript [Website] how ChatGPT appears to be a helpful editor but continually makes the same mistakes over and over again (Guinzburg).

Companies like OpenAI are working to correct this problem, but we have already seen how harmful this tendency can be (Heikkilä; Prada). This problem is compounded by people failing to recognize or remember that the chatbot they are “speaking” with is not sentient and does not have any intention behind its language generation. In extreme cases, this has led people to “ChatGPT-induced psychosis,” even causing them to take their own lives because the chatbot fed a delusion (Hill).

AI Companies as Rhetors

Generative AI and LLMs are created by tech companies such as OpenAI, Google, and Microsoft. While we are told that AI will improve our work productivity or create new job opportunities, research has shown that the opposite has been true so far (Demirci et al.). Furthermore, the people investing in and creating this technology don’t seem interested in improving wages or working conditions; if anything, the opposite is more likely (Landymore). And even though we have seen massive rollouts of AI across business sectors, it is unclear whether the business models behind these companies are sustainable (McMahon). Additionally, remember how we explained that LLMs work on probabilistic algorithms to predict the next token in a sequence? As that example showed, humans can’t be completely eliminated from this process. Tech companies need humans, but they have generally relied on exploited labor from developing countries to avoid paying living wages (Dinika).

As various industries adopt AI tools, workers in these fields have raised concerns about how this will affect — or potentially eliminate — their jobs. For instance, both actors and writers made AI a central issue during the Hollywood strikes in 2023 (Scherer). More recently, Disney and Universal Studios have filed lawsuits against Midjourney, an AI image generation company, for copyright infringement; OpenAI has previously argued that disregarding copyright is necessary for their continued operations (Veltman; Espiner and Jamali; Al-Sibai).

Finally, remember how we talked about AI having a particular style or tone earlier? This is also true of the images that AI generates. This aesthetic has been termed “AI slop,” and it has been increasingly prevalent on social media (Mahdawi, Roozenbee, et al.). Sometimes these take the form of cute recreations of characters in the style of Studio Ghibli or Disney (which is why Disney is filing a lawsuit), but they have also been used to spread misinformation (Jingnan) This is particularly prevalent among far-right-wing conservative political groups, which have embraced not only the technology but its aesthetics as well (Gilbert; Watkins).

Dig Deeper: The Problem with AI-Generated Images

Figure 20.2. Cover of Cyborgs and Centaurs: Academic Writing in the Age of Generative AI. [Image Description]

This is the cover image for rhetorician and composition professor Liza Long’s open-educational textbook, Cyborgs and Centaurs: Academic Writing in the Age of Generative Artificial Intelligence.

In the opening chapter, Long uses her attempt to generate a cover image with AI as a way to represent some of the problems of AI in terms of image creation and output more generally. She writes, “It’s probably clear to you that I used a generative artificial intelligence tool (DALL-E 3 through ChatGPT 4o) to create this image. I started an entertaining journey of image creation misadventures with this simple prompt:

“Can you please draw an image of a centaur shaking hands with a cyborg? The centaur and cyborg should be in the center of the image, with a rainbow and mountains blurred in the background. Use a high fantasy art style.”

Spoiler alert: It really couldn’t do this. We engaged in a series of back-and-forths where I tried to teach it what centaurs and cyborgs are, and it told me, without blushing, that there was no horn on the man’s head. Here’s the version of the prompt I used to get the cover result:

“I want two central images. 1. A centaur. A centaur has a human (man or woman) head and torso and hands. It has a horse’s body, flanks, four legs, and tail. 2. A cyborg. A cyborg is part human and part machine. It has two legs like a human and stands on two legs. Please use a whimsical children’s book illustration style and include a rainbow and mountains in the background” (Open AI, 2024).

What I got instead was this: a mishmash image of a human unicorn/centaur shaking hands with a robot centaur. The rainbow looks good, though. (Source: What’s wrong with this picture? [Website]).

Reflection

Use your past experiences with AI to answer the following questions:

- Have you tried to generate images using AI?

- What have the results been like?

- Have you run into the same problems Long encountered in the example above?

- Have you found any differences depending on the kind of request or prompt you input?

- What are AI image generators good at, and what are they bad at?

Audiences

The previous section discusses the wider context behind the use and spread of generative AI technologies. The next element of the rhetorical situation for us to consider is audience — how has the general public responded to the proliferation of this technology and its outputs? In 2024, companies such as Coca-Cola and Skechers started publishing AI-generated advertisements for their products (Funaki; Berger). These were met with backlash from customers, who associated the use of AI with the company being cheap by refusing to hire and pay real artists for their work.

The previous section discusses the wider context behind the use and spread of generative AI technologies. The next element of the rhetorical situation for us to consider is audience — how has the general public responded to the proliferation of this technology and its outputs? In 2024, companies such as Coca-Cola and Skechers started publishing AI-generated advertisements for their products (Funaki; Berger). These were met with backlash from customers, who associated the use of AI with the company being cheap by refusing to hire and pay real artists for their work.

Dig Deeper: AI Advertisements

Coca-Cola tried to generate excitement for its 2024 Christmas ad campaign by promoting it as one of the first to use all AI-assisted images — with no human actors at all. Yet, as mentioned above, the campaign was met with both ethical and aesthetic criticisms.

After watching the commercial, check out the comments on YouTube below the video. Based on both the comments and your own evaluation, reflect on the benefits and drawbacks of AI-generated advertisements in terms of audience experience.

Additionally, while individual viewers might not be concerned about copyright law or intellectual property, it is still important for us to think about how these technologies encroach on our data privacy. For instance, a privacy watchdog organization in Italy has fined OpenAI for ChatGPT’s violations in collecting users’ personal data (Zampano). These findings have been confirmed in a recent report from the research institute AI Now (Brennan et al.).

In education, universities have been adding instruction on AI to their curricula to help prepare students for the future. For instance, The Ohio State University recently announced that each of their students would graduate with AI fluency (“AI Fluency | Office of Academic Affairs”). More locally, USF hosts programs like the Center for AI & Data Ethics and the Strategic Artificial Intelligence Program. And of course, AI technologies are already being used by professors and students in their classrooms.

However, the use of AI in academic contexts has not been universally popular or accepted. Notably, a student at Northeastern University filed a formal complaint and demanded a refund of her tuition when she discovered that her professor was using ChatGPT to generate lecture notes and other course materials (Nolan). Similarly, students at the University of Auckland in New Zealand have pushed back on the use of AI tutors in business and economics courses (Franks and Plummer). This kind of AI use on campuses has been controversial among students because it suggests that the university and professors do not care enough about their education to do this work themselves. Research from education also shows that the uncritical use of AI tools has a negative effect on students’ learning and exam scores (Bastani et al.; Wecks et al.). Some students are already thinking about the long-term effects of this technology on their education and achievements, as the Financial Times reports that “multiple students the FT spoke to, who asked to remain anonymous, also worry about being perceived negatively as the AI generation. One of them expressed anxiety about being ‘guinea pigs’ for the AI pilots taking place before the impact of the technology on learning is fully known” (Criddle and Jack).

Outside of the classroom, a university’s use of AI can also be perceived as a lack of care for students, such as when Vanderbilt University sent a ChatGPT-generated message of support following a mass shooting (Petri; see the original email here).

Another field where generative AI has met resistance is in mental health and counseling. Chatbots are being used by organizations such as the National Eating Disorders Association to run their helpline, but some of the results have been harmful to users (“An Eating Disorders Chatbot Offered Dieting Advice”; “Can a Chatbot Help People with Eating Disorders As Well As Another Human?”).

Subject

When we talk about “the subject” in the rhetorical situation, we are usually referring to the text itself: what it says and how it is presented. While there are various ways that generative AI might be used to create or contribute to your work, we’ll focus on LLMs for now.

One problem for academic writing is that generative AI chatbots do not cite their sources. Teachers will usually ask you to cite your sources, right? They will explain that you should cite not just when you are quoting but also when you are referencing an idea you got from someone else. The purpose of this is to communicate to readers where we’ve sourced facts and ideas from, and to avoid intellectual theft. We can think of academic work as a big, ongoing conversation between people agreeing, disagreeing, and building on each other’s points as they try to figure things out. It’s only fair to give people credit for their contributions to the conversation.

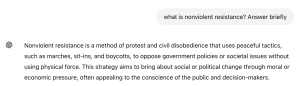

For some concepts in the humanities and social sciences, it is also important to know the positionality of the person or people who developed them. For example, if we are studying nonviolent resistance, we need to understand the people and context in which ideas about it were developed. Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Junior, and Henry David Thoreau wrote extensively about it, and their ideas were shaped by very different experiences, times, and places.

Knowing something about how these leaders were positioned in terms of race, gender, class, education, and politics can help us understand their ideas and think about how we want to respond from our own positionality. However, if you ask a chatbot about “nonviolent resistance,” it may give you an answer without reference to any person or context at all (chatbot responses are variable). Here is an example from ChatGPT:

Figure 20.3. Screenshot from a ChatGPT4o temporary session, July 2024. (Chat_Screenshot_Accessible Word doc [New Tab])

In general, chatbots don’t make it easy to figure out what sources have influenced their answers. As Iris Van Rooij puts it, “LLMs, by design, produce texts based on ideas generated by others without the user knowing what the exact sources were” (Van Rooij).

The systems don’t “know” what influenced their answer. Once a system is trained, it consists of a very complicated formula, a big set of numbers that it’s supposed to multiply by other numbers. The chatbot puts our question or request into the formula and gets a result. It has no way to look backward to see which human writings influenced its formula.

A related problem is that the information provided by LLMs might not even be true. Remember that the task of LLMs is simply to predict the next token given an input; it so happens that if you train them on enough data, you begin to see emergent capabilities from the act of token prediction (e.g., the ability of LLMs to write computer code and simulate reasoning capabilities). But this prediction is also the reason why some researchers insist that LLMs are merely tools of natural language generation and not natural language understanding, even though it can seem that way to users.

These models don’t operate with an understanding of the world, or any “ground truth;” they work statistically. They model language based on associated terms and concepts in their datasets, always predicting the next word (in units called “tokens”) formulaically. This is the reason language models can convey false information or “hallucinate”. They don’t know false from true — only statistical relationships between tokens. For more information on how to cite text generated by an LLM, see the “Composing with Generative AI” chapter.

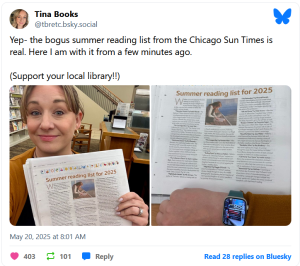

Dig Deeper: AI Hallucinations

Even professional media outlets have been caught using AI-generated research that contains multiple “hallucinations.” Check out this NPR article [Website] about the Chicago Sun Times’ May 2025 “Summer Reading List” article, in which only five out of the 15 suggested book titles for summer reading are actually real.

Figure 20.4. Bluesky post by Tina Brooks [Image Description]

Hallucination has not been the only problem with LLMs. When GPT-3 was released in 2020, researchers used adversarial testing to coax all manner of toxic and dangerous outputs from the model. This became something of a social media game when ChatGPT was released, as users made every attempt to “jailbreak” it in an attempt to get it to say nasty things. Numerous reports and swirling internet rumors suggested LLMs might provide good instructions for making methamphetamine or chemical weapons using ingredients available from Home Depot.

In academic publishing, The Quarterly Journal of Economics almost published an article that turned out to have been fabricated by ChatGPT, including the research data. You can read more about that incident here, but the important takeaway is that this problem affects academic writing even at the highest levels (Shindel)!

Context

The context of the rhetorical situation is the combination of factors that enable or constrain how a text is produced. In the case of generative AI, one major context that makes this technology possible is the energy needed to power it. The environmental costs of AI have been well documented by researchers, journalists, and others concerned for the future of planet Earth:

- “The Climate and Sustainability Implications of Generative AI”[Website] by Bashir, Donti, Cuff, et al.

- “Making AI Less ‘Thirsty’: Uncovering and Addressing the Secret Water Footprint of AI Models” [Online PDF] by Li, Yang, Islam, and Ren

- “The Environmental Impacts of AI – Primer” [Website] by Luccioni, Trevelin, and Mitchell

- “The ugly truth behind ChatGPT: AI is guzzling resources at planet-eating rates” [Website] by Mariana Mazzucato

- “Measuring the environmental impacts of artificial intelligence compute and applications” [Website] from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- “How much water does AI consume? The public deserves to know” [Website] by Shaolei Ren

Futures for Generative AI and Writing

Despite Big Tech’s insistence that these technologies will sweep the world, there are a number of variables that will affect their trajectory as writers determine the extent to which writing with AI is viable. These variables include:

- Scale and access: Can engineers create language models that achieve decent performance without using extraordinary computing resources? If the technologies remain expensive to use and operate, what does it mean for access? Data at a large scale is impossible to review for accuracy or bias. Can language models be too big?

- Security and privacy: To what extent do language models leave users vulnerable to breaches of personal information, either in using the models or in having their data used as part of the training set for the models? What security is possible in locally run instances of language models?

- Legality: Who will be liable for the harms created by the output of generative AI? Is it fair use for generative AI to mimic the styles of living authors and artists? How will copyright case law develop?

- Implementation and user experience: How seamlessly will AI writing applications be integrated into now-standard technologies such as word processors and email clients? To what degree will writers or educators be able to decide on the level of integration or visibility of use for these language models?

- Fact and ground truth: What methods will be developed to decrease inaccuracies (such as hallucinations of scholarly references or historical facts) in language models? Can reinforcement learning or connections to established databases prevent language models from their tendency to produce incorrect responses?

- Complementary technologies: What will language models be capable of when they are integrated into other applications? To what degree will AI language models shape our digital discourse?

- Abuse by malicious actors: Will the benefits of generative AI outweigh the potential harms it can create, such as supporting disinformation campaigns?

- Identification and disclosure: Software for detecting AI-generated text has not proven to be particularly effective. A variety of solutions have been proposed, but for the time being it seems to be a cat-and-mouse game that’s initiating a crisis of social trust related to certain kinds of writing.

- Social stigma: Upon its arrival, ChatGPT received intense press coverage that framed it as a cheating technology for students. To what extent will collective impressions of the technology shape its trajectory?

- Style and language bias: Language models write with “standard” grammar in languages that are well-represented in the dataset, such as English. Given significant bias against “accented” writing in educational and professional contexts, how will language models affect writers’ or readers’ perceptions of “accent” in writing?

- Lesser-known or minoritized languages: How will languages and discourse with little or minoritized representation in the training data be reflected in language models? Will smaller language models be tailored for use by these discourse or language communities? Will supervised learning or synthetic data supplement training be used to enhance representation? To what degree will minoritized discourse communities embrace language models?

Conclusion

If or when you decide to use AI as part of your composing and communication process, it will be important to think about not just how it can be helpful, but the cost that comes with it. Bias, censorship, and hallucinations aren’t just abstract concepts, but tangible risks that can subtly influence and distort your writing. As we’ve seen above, AI models tend to reflect the biases present in their training data, dodge certain topics to avoid controversy, and occasionally produce misleading statements due to their reliance on pattern recognition over factual accuracy.

Moreover, your unique voice, the individual perspective shaped by your experiences, and the deep-seated beliefs that guide your understanding are vital components of your writing process. An overreliance on AI models could inadvertently dilute this voice, even leading you to echo perspectives you may not fully agree with.

In the realm of rhetoric and other courses, it’s also essential to remember that AI is a tool, not a substitute. It can aid in refining your work, sparking creativity, and ensuring grammatical accuracy. However, students must learn to distinguish between capabilities such as idea generation (which LLMs are great at) and the ability to judge something as beautiful (which LLMs currently cannot do).

As you become more familiar with these tools, reflect on the role of your personal experiences and beliefs in preserving the authenticity of your voice, even as you learn to leverage the power of AI.

Activity 1: Evaluating Sources

In your group, you will review 3 sources:

- Opposing Viewpoints: Artificial Intelligence [Website]

- A Study Found That AI Could Ace MIT. Three MIT Students Beg to Differ [Website]

- How to cheat on your final paper: Assigning AI for student writing [Online PDF]

Please take notes on who the audience is for each source, what the differences are between all of them, and how you would use them in research. Designate one person in your group to report your observations and one person to take notes.

Activity 2: Engaging with AI and Research Tools

In your group, you will conduct a search using three research tools: ChatSonic [Website], Academic Search Complete [Library Link], and Fusion [Library Link]. With your group, choose a topic to search in these three tools and write your answers in the table below:

- How many results come up in each search?

- What does each tool search for?

- How is this useful for you?

- What limitations do you see?

Designate one person in your group to report your observations and one person to take notes.

Research Tools:

Further Reading and Resources

For further reading on the relationship between generative AI and linguistic justice, see these resources:

- “Linguistic Justice and GenAI” [Website]

- “GenAI: The Impetus for Linguistic Justice Once and For All” [Online PDF]

- “An Indigenous perspective on AI and the harm it can cause on our communities (a thread, made by me)” [Website]

Works Cited

Adio Dinika. “The Human Cost of Our AI-Driven Future.” NOEMA, 25 Sept. 2024, www.noemamag.com/the-human-cost-of-our-ai-driven-future/.

“AI Fluency | Office of Academic Affairs.” Osu.edu, 2025, oaa.osu.edu/ai-fluency.

Al-Sibai, Noor. “OpenAI Pleads That It Can’t Make Money without Using Copyrighted Materials for Free.” Futurism, 8 Jan. 2024, futurism.com/the-byte/openai-copyrighted-material-parliament.

Arwa Mahdawi. “AI-Generated ‘Slop’ Is Slowly Killing the Internet, so Why Is Nobody Trying to Stop It?” The Guardian, 8 Jan. 2025, www.theguardian.com/global/commentisfree/2025/jan/08/ai-generated-slop-slowly-killing-internet-nobody-trying-to-stop-it.

Bashir, Noman, et al. “The Climate and Sustainability Implications of Generative AI.” An MIT Exploration of Generative AI, March 2024, https://doi.org/10.21428/e4baedd9.9070dfe7.

Bastani, Hamsa, et al. Generative AI Can Harm Learning. hamsabastani.github.io/education_llm.pdf.

Berger, Chloe. “Skechers Draw Backlash for Full-Page Ad in Vogue That Reeks of AI. ‘You Actually Didn’t Save Any Money Because Now I Hate You.‘”Yahoo News, 14 Dec. 2024, www.yahoo.com/news/skechers-draw-backlash-full-page-063600662.html.

Bjork, Collin. “ChatGPT Threatens Language Diversity. More Needs to Be Done to Protect Our Differences in the Age of AI.”The Conversation, 9 Feb. 2023, theconversation.com/chatgpt-threatens-language-diversity-more-needs-to-be-done-to-protect-our-differences-in-the-age-of-ai-198878.

Blair, Elizabeth. “How an AI-Generated Summer Reading List Got Published in Major Newspapers.” NPR, 20 May 2025, www.npr.org/2025/05/20/nx-s1-5405022/fake-summer-reading-list-ai.

Boyer, Danielle [@danielleboyerr]. “An Indigenous perspective on AI and the harm it can cause on our communities (a thread, made by me).” X, 12 Nov. 2024, 4:03 p.m., https://x.com/danielleboyerr/status/1856488128682549713.

Brennan, Kate, et al. “Artificial Power: 2025 Landscape Report.” AI Now Institute, 3 June 2025, ainowinstitute.org/publications/research/ai-now-2025-landscape-report.

Brooks, Tina. “Screenshot 2025-07-01 163250.” Bluesky, 1 July 2025, https://bsky.app/profile/did:plc:izv2d6gdu2xqtzdc4wyrclax/post/3lpme473fdc2z.

“Center for AI & Data Ethics – Data Institute | University of San Francisco.” Usfca.edu, 2024, www.usfca.edu/data-institute/centers-initiatives/caide.

Coca-Cola. “The Holiday Magic Is Coming.” YouTube, 18 Nov. 2024, www.youtube.com/watch?v=4RSTupbfGog.

Criddle, Cristina, and Andrew Jack. “Chatbots in the Classroom: How AI Is Reshaping Higher Education.” Financial Times, 18 July 2025, www.ft.com/content/adb559da-1bdf-4645-aa3b-e179962171a1.

Demirci, Ozge, et al. “Research: How Gen AI Is Already Impacting the Labor Market.” Harvard Business Review, Nov. 2024, hbr.org/2024/11/research-how-gen-ai-is-already-impacting-the-labor-market.

Denney, L. “Your Body, Your Choice: At Least, That’s How It Should Be.” Beginnings and Endings: A Critical Edition, 2023, cwi.pressbooks.pub/beginnings-and-endings-a-critical-edition/chapter/feminist-5/.

Espiner, Tom. “Artificial Intelligence: Disney and Universal Sue Midjourney over Copyright.” BBC, 12 June 2025, www.bbc.com/news/articles/cg5vjqdm1ypo.

Franks, Raphael, and Benjamin Plummer. “University of Auckland Students Criticise Introduction of Artificial Intelligence Tutors in Business and Economics Course.” NZ Herald, 28 Feb. 2025, www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/university-of-auckland-students-criticise-introduction-of-artificial-intelligence-tutors-in-business-and-economics-course/EKNMREEVPZEY7E2P7YNUYKHWUY/.

Funaki, Kaiyo. “Coca-Cola Issues Statement amid Widespread Backlash over 2024 Christmas Commercial: ‘the World Is so Over.’” Yahoo News, 2 Dec. 2024, www.yahoo.com/news/coca-cola-issues-statement-amid-104556512.html.

Gawronski, Haley. “Coaches Attend a Leadership Seminar Headed by the U.S.” Picryl, 15 Dec. 2018, picryl.com/media/coaches-attend-a-leadership-seminar-headed-by-the-us-0afe21.

Gilbert, David. “Neo-Nazis Are All-in on AI.” WIRED, 20 June 2024, www.wired.com/story/neo-nazis-are-all-in-on-ai/.

Guinzburg, Amanda. “Diabolus Ex Machina.” Substack.com, Everything Is A Wave, June 2025, amandaguinzburg.substack.com/p/diabolus-ex-machina.

Heikkilä, Melissa. “AI Chatbots Tell Users What They Want to Hear, and That’s Problematic.” Ars Technica, 12 June 2025, arstechnica.com/ai/2025/06/ai-chatbots-tell-users-what-they-want-to-hear-and-thats-problematic/.

Hill, Kashmir. “They Asked ChatGPT Questions. The Answers Sent Them Spiraling.” The New York Times, 13 June 2025, www.nytimes.com/2025/06/13/technology/chatgpt-ai-chatbots-conspiracies.html?unlocked_article_code=1.Ok8.VBY-.s76GQpFar8r4&smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare.

Jingnan, Huo. “AI-Generated Images Have Become a New Form of Propaganda This Election Season.” NPR, 18 Oct. 2024, www.npr.org/2024/10/18/nx-s1-5153741/ai-images-hurricanes-disasters-propaganda.

Jory, Justin. “Rhetorical Situation Model.” Open English @ SLCC, Pressbooks, pressbooks.pub/openenglishatslcc/chapter/the-rhetorical-situation/.

Landymore, Frank. “Top AI Investor Says Goal Is to Crash Human Wages.” Futurism, 27 Jan. 2025, futurism.com/the-byte/ai-investor-goal-crash-human-wages.

Li, Pengfei, et al. “Making AI Less “Thirsty”: Uncovering and Addressing the Secret Water Footprint of AI Models. 26 Mar. 2025, arxiv.org/pdf/2304.03271.

“Linguistic Justice and GenAI.” Sweetland Center for Writing. University of Michigan, lsa.umich.edu/sweetland/instructors/guides-to-teaching-writing/linguistic-justice-genai.html.

Long, Liza. “Cyborgs and Centaurs cover image.” Cyborgs and Centaurs: Academic Writing in the Age of Generative Artificial Intelligence, College of Western Idaho Pressbooks, 2023, cwi.pressbooks.pub/longenglish102/chapter/chapter-one-introduction/.

Luccioni, Sasha, et al. “The Environmental Impacts of AI — Primer.” Huggingface.co, 2024, huggingface.co/blog/sasha/ai-environment-primer.

Mazzucato, Mariana. “The Ugly Truth behind ChatGPT: AI Is Guzzling Resources at Planet-Eating Rates.” The Guardian, 30 May 2024, www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/may/30/ugly-truth-ai-chatgpt-guzzling-resources-environment?CMP=fb_a-technology_b-gdntech.

McAdoo, Timothy. “How to Cite ChatGPT.” APA Style Blog, 7 Apr. 2023, apastyle.apa.org/blog/how-to-cite-chatgpt.

McMahon, Bryan. “Bubble Trouble.” The American Prospect, 25 Mar. 2025, prospect.org/power/2025-03-25-bubble-trouble-ai-threat/.

“Measuring the Environmental Impacts of Artificial Intelligence Compute and Applications.” OECD, 2024, www.oecd.org/en/publications/measuring-the-environmental-impacts-of-artificial-intelligence-compute-and-applications_7babf571-en.html.

Mills, Anna. “Mills AI conversation. “How Arguments Work – A Guide to Writing and Analyzing Texts in College”, LibreTexts, 13 May 2025, human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Composition/Advanced_Composition/How_Arguments_Work_-A_Guide_to_Writing_and_Analyzing_Texts_in_College(Mills)/16%3A_Artificial_Intelligence_and_College_Writing/Don’t_Trust_AI_to_Cite_Its_Sources.

Modern Language Association. “How Do I Cite Generative AI in MLA Style?” MLA Style, 17 Mar. 2023, style.mla.org/citing-generative-ai/.

Monash University. “Acknowledging the Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence.” Monash University Learn HQ, www.monash.edu/learnhq/build-digital-capabilities/create-online/acknowledging-the-use-of-generative-artificial-intelligence.

Nolan, Beatrice. “Northeastern College Student Demanded Her Tuition Fees Back after Catching Her Professor Using OpenAI’s ChatGPT.” Fortune, 15 May 2025, fortune.com/2025/05/15/chatgpt-openai-northeastern-college-student-tuition-fees-back-catching-professor/.

OpenAI. “Yellow Wallpaper themes.” ChatGPT, 24 May version, 2023. Large Language Model, chat.openai.com/share/70e86a32-6f04-47b4-8ea7-a5aac93c2c77.

Petri, Alexandra E. “Vanderbilt University Apologizes for ChatGPT Email about Shooting.” Los Angeles Times, 22 Feb. 2023, www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2023-02-22/vanderbilt-university-apologizes-chatgpt-email-michigan-state-shooting.

Prada, Luis. “AI Chatbots Are Telling People What They Want to Hear. That’s a Huge Problem.” VICE, 8 June 2025, www.vice.com/en/article/ai-chatbots-are-telling-people-what-they-want-to-hear-thats-a-huge-problem/.

Purdue Writing Lab. “Footnotes & Appendices.” Purdue Writing Lab, owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/footnotes_appendices.html.

Ren, Shaolei. “How Much Water Does AI Consume? The Public Deserves to Know – OECD.AI.” Oecd.ai, 30 Nov. 2023, oecd.ai/en/wonk/how-much-water-does-ai-consume.

Roozenbeek, Jon, et al. “What Is AI Slop? Why You Are Seeing More Fake Photos and Videos in Your Social Media Feeds.” The Conversation, 28 May 2025, theconversation.com/what-is-ai-slop-why-you-are-seeing-more-fake-photos-and-videos-in-your-social-media-feeds-255538.

Scherer, Matt. “The SAG-AFTRA Strike Is Over, but the AI Fight in Hollywood Is Just Beginning.” Center for Democracy and Technology, 4 Jan. 2024, cdt.org/insights/the-sag-aftra-strike-is-over-but-the-ai-fight-in-hollywood-is-just-beginning/.

Shindel, Ben. “AI, Materials, and Fraud, Oh My!” Substack.com, The BS Detector, 16 May 2025, thebsdetector.substack.com/p/ai-materials-and-fraud-oh-my.

“Strategic Artificial Intelligence Program.” University of San Francisco, 2015, profed.usfca.edu/strategic-artificial-intelligence.html.

Thompson, Faith, and Lauren Hatch Pokhrel. “GenAI: The Impetus for Linguistic Justice Once and For All.” Literacy in Composition Studies, vol. 11, no. 2, 2024, pp. 68–79, https://licsjournal.org/index.php/LiCS/article/view/3132.

Van Rooij, Iris. “Against Automated Plagiarism.” Iris van Rooij, 29 Dec. 2022, irisvanrooijcogsci.com/2022/12/29/against-automated-plagiarism/.

Veltman, Chloe. “In First-of-Its-Kind Lawsuit, Hollywood Giants Sue AI Firm for Copyright Infringement.” NPR, 12 June 2025, www.npr.org/2025/06/12/nx-s1-5431684/ai-disney-universal-midjourney-copyright-infringement-lawsuit.

Watkins, Gareth. “AI: The New Aesthetics of Fascism.” New Socialist, 9 Feb. 2025, newsocialist.org.uk/transmissions/ai-the-new-aesthetics-of-fascism/.

Wecks, Janik Ole, et al. “Generative AI Usage and Academic Performance.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2024, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4812513.

Weiss, Katherine, and Cade Metz. “When A.I. Chatbots Hallucinate.” The New York Times, 9 May 2023, www.nytimes.com/2023/05/01/business/ai-chatbots-hallucination.html.

Wells, Kate. “An Eating Disorders Chatbot Offered Dieting Advice, Raising Fears about AI in Health.” NPR, 8 June 2023, www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/06/08/1180838096/an-eating-disorders-chatbot-offered-dieting-advice-raising-fears-about-ai-in-hea.

Wells, Kate. “Can a Chatbot Help People with Eating Disorders as Well as Another Human?” NPR, 24 May 2023, www.npr.org/2023/05/24/1177847298/can-a-chatbot-help-people-with-eating-disorders-as-well-as-another-human.

Zampano, Giada. “Italy’s Privacy Watchdog Fines OpenAI for ChatGPT’s Violations in Collecting Users Personal Data.” AP News, 20 Dec. 2024, apnews.com/article/italy-privacy-authority-openai-chatgpt-fine-6760575ae7a29a1dd22cc666f49e605f.

Image Descriptions

Figure 20.2. Whimsical, pastel illustration showing two figures centered beneath a bright rainbow: at left, a white unicorn with a human body wearing tan boots and clothing and a blue scarf; at right, a silver humanoid robot fused to a horse’s hindquarters with a target-like symbol on its flank. They stand on grass and shake hands. A distant blue mountain range, small trees, and soft clouds sit in the background. The scene is symmetrically composed and uses clean lines and muted colors, evoking a friendly meeting of fantasy and technology. [Return to Figure 20.2]

Figure 20.4. A screenshot of a post by Tina Books (@tbretct.bsky.social). Post text reads: “Yep- the bogus summer reading list from the Chicago Sun Times is real. Here I am with it from a few minutes ago. (Support your local library!!)” Below are two photos: (1) a selfie of a woman in a library holding up a newspaper opened to a page titled “Summer reading list for 2025,” and (2) a close-up of the same page on a tabletop with a smartwatch visible on her wrist. Footer shows May 20, 2025 at 8:01 AM, reaction counts (403 and 101), a Reply button, and a link that says “Read 28 replies on Bluesky.” [Return to Figure 20.4]

Attributions

This chapter was written and remixed by Phil Choong.

“The Problem with AI Generated Images” section was adapted from “What’s Wrong with This Picture?” by Liza Long and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Parts of the “Subject” section were adapted from “Don’t Trust AI to Cite Its Sources” by Anna Mills and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Parts of the “Subject” section and the “Futures for Generative AI and Writing” section were adapted from “An Introduction to Teaching with Text Generation Technologies” by Tim Laquintano, Carly Schnitzler, and Annette Vee and is licensed under CC BY-NC.

The “Conclusion” section was adapted from “How Do Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT Work?” by Joel Gladd and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Media Attributions

- Rhetorical Situation Model © Justin Jory is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Cyborgs and Centaurs cover image © Liza Long is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Coaches attend a leadership seminar headed by the U.S. © Haley Gawronski is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Mills AI conversation © Anna Mills is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Screenshot 2025-07-01 163250 © Tina Brooks