9 Why Do Professors Talk Like That?

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Explain the connection between academic language norms and the shared goals and values of academia

- Identify characteristics of academic discourse that are shared across fields

- Identify variations in language norms across academic fields (e.g., humanities vs. sciences) and how these align with the goals and values of those fields

- Reflect on the language norms of your own major or primary field of study

- Evaluate the benefits and drawbacks of academic language norms for achieving the goals of the field — as well as for inclusion and equity

I love what’s in academic discourse: learning, intelligence, sophistication — even mere facts and naked summaries of articles and books; I love reasoning, inference, and evidence; I love theory. But I hate academic discourse.

–Peter Elbow

If you’ve ever read a scholarly article and thought, “Why does this sound so complicated and hard to understand?”, you’re not alone. Academic language has a particular flavor — formal, precise, and dense. For some readers, it can feel as foreign as another language. And in some ways, it is like a foreign language, because nobody grows up speaking it — it’s nobody’s “native tongue.” This might make us ask: “Why do academics talk like that?”

Reflection

Describe your best and worst college writing or reading experiences. How different were they from your high-school writing or reading experiences? What was most challenging? What are you most proud of? Have expectations for “good college writing” been consistent or varied in the classes you’ve taken so far? Have professors explicitly taught you how to write or read academic discourse, or have they assumed prior knowledge and experience?

Further complicating the idea and use of academic discourse is the fact that language norms vary widely across academic fields. The way a historian crafts an argument looks different from how a biologist reports their findings — and that’s because rules for communication in each field align with that field’s distinct goals. Broadly speaking, historians tend to prioritize narrative and interpretation, while biologists emphasize precision and replicability.

Given this variation, is there even such a thing as “academic discourse”? This is a real subject of debate in the field of rhetoric, and teachers and scholars continue to argue about whether or not the “generic academic writing” typically taught in first-year college composition classes actually reflects the writing students “will need to produce in the rest of their college career and beyond” (Donahue and Foster-Johnson). We’ll come back to this argument later in the chapter.

At the same time, you’ve probably seen some commonalities across the writing and reading you’ve been exposed to in your college classes, so let’s think about that first.

Student Voices: From Academic “Outsider” to “Insider”

As part of my learning experience and development as an intern at a neuroscience lab in SF, I was asked to prepare and present a Journal Club Presentation to our building-wide Journal Club. Throughout that experience, several language ideologies contributed to my feeling [of being] an “outsider.” The audience that I was presenting to was highly educated with PhDs and decades of experience in psychology and neuroscience, so they used a specialized language and style of speaking that represented their intelligence, skill, and authority in the field. This created a feeling of hierarchy, making me feel that my style of speaking was “lesser,” proving my lack of higher education at the time.

While practicing my presentation with my principal investigator (PI), he made comments such as “This is just a thing we do in academia” and “This is how we write xyz in psychology research.” These remarks made me realize that academia has a preferred, higher-ranked way of communicating. This differed from what I was taught in classes throughout my education. This reinforced the idea of linguistic discrimination, where certain ways of writing and speaking are considered more valid than others.

Since I was expected to be an “expert,” I needed to understand the material thoroughly, but also be prepared to engage with the audience’s critiques, questions, and discussions. After doing the presentation, I felt a sense of accomplishment because it felt like my own personal entrance or gateway into the field.

That experience definitely made me reflect on how language differs among groups — specifically, how schools approach language instruction. Much of my education focused on analyzing texts that were written by older white men. Books that were written by people not fitting that description were typically scrutinized, and their language was compared to the “Standard English” of our taught books. This approach implied that there is a single “proper” way of speaking, which fails to recognize that there’s any validity to other ways of speaking and linguistics. What strategies can schools promote to increase linguistic diversity and diverse forms of communication in classrooms?

–Sadie Hicks, 2025

Sadie is a psychology major at USF.

The Dos and Don’ts of Academic Discourse

Figure 9.1. Academic Discourse Community. (Academic_Discourse_Community_Accessible [New Tab])

The following video reviews some of the common expectations for academic discourse that appear across fields. Does any of this sound familiar? Where do you recognize “rules” and where and when have you seen them challenged, either implicitly or explicitly?

Watch: “Essential Rules For Academic Writing | Student Tips” (~6 mins)

Broadly speaking, these “rules” reflect many of the values and goals of the university and academia. They include:

- Sources and citations: Citing sources helps readers know where information is coming from, so we can evaluate its credibility. Further, citations can help advance our overall knowledge, because they require authors and researchers to actually read and engage in others’ work first, so that the same arguments and discoveries aren’t simply repeated over and over again.

- Vocabulary: Academic vocabulary is formal and precise, because specificity and nuance matter when the message is complex. It frowns on slang because it can mean different things to different people, and not all audiences will share the same casual lingo.

- Style and structure: Academic discourse prioritizes clarity and explicitness, because the goal is knowledge, not entertainment. It has strict rules for organization and structure, because it saves time by enabling the reader to quickly find where the important information is, or how a study was conducted. Even the elimination of the first person (“I”) is a way of requiring that authors move beyond their personal opinions, which could be partial or biased.

- Argument and evidence: Academic discourse requires clear reasons and strong evidence so that we have a way of figuring out which arguments we should trust and which we shouldn’t.

As this list shows, these rules aren’t random — they often have good reasons behind them.

But many of these rules can make writing feel less fun, less conversational, and less engaging. It can make you sound like a robot instead of a living, breathing human being. It can make some of the most enjoyable ways of writing and reading, like storytelling, totally off-limits. In fact, as composition scholar Peter Elbow argues, it can stop students from wanting or liking to write or read (96).

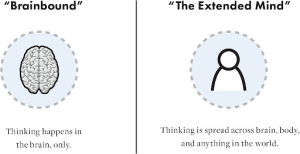

Further, Elbow has also [YouTube Video] suggested that the demand for “writing language” instead of “talking language” comes from a bias that elevates the mind over the body, ignoring or discounting how the body can be an important channel for knowing and communicating (westernmasswp).

Figure 9.2. Elbow suggests that “academic discourse” assumes the first model (“brainbound”), ignoring the alternative (“the extended mind”). (Brainbound_vs_Extended_Mind_Accessible [New Tab])

In short, we need to recognize both the powerful benefits and the potential challenges of these academic “rules” — challenges we’ll explore more below as we begin to compare and contrast norms across disciplines.

A Closer Look: Anatomy of a Scholarly Article

Click on the various sections of the interactive tool Anatomy of a Scholarly Article [Website] to identify specific components of a scholarly article.

This “anatomy” demonstrates that many academic fields have similar writing conventions, namely the standard “IMRaD” structure: introduction, methods, results, and discussion. However, even this structure is somewhat field-specific; it’s widely used across the natural sciences (biology, chemistry, etc.), but notably less common in the humanities.

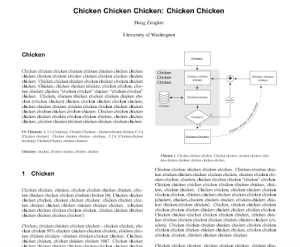

This structure works as a useful shortcut, helping writers remember what to include and helping readers know where to find specific information. But sometimes these “rules” can take on a life of their own. Check out Doug Zongker’s “Chicken, Chicken, Chicken” [Online PDF] paper, which makes fun of the IMRaD structure by showing how it can make even a bunch of total nonsense look “official” or “legitimate.”

Variation Across Fields (Why Is My Biology Paper Different from My History Paper?)

The fact is that we can’t teach academic discourse because there’s no such thing to teach. Biologists don’t write like historians. This is not news.

–Peter Elbow

What if, as Peter Elbow suggests above, the category of “academic discourse” doesn’t actually exist? As much as the rules above might be generally shared, there are plenty of other rules that are followed by some disciplines, but not others. Even when fields share a general rule, there’s still some variation. For example, as discussed above, all disciplines care about citation and giving credit to others for their work. But one of the first differences you might notice when writing and reading in different fields is the citation styles, or the specific elements that are required in one type of citation versus another. To see what I mean, check out the differences between two of the most common styles, American Psychological Association (APA) and Modern Language Association (MLA), below:

Figure 9.4. MLA vs. APA Infographic. (MLA_vs_APA_Accessible [New Tab])

Why are they different? Is it just to annoy you and lose you points when you accidentally write an English paper with APA-formatted citations, or a Chemistry paper with MLA citations? Well, no (although sometimes it can seem that way!).

Much like day-to-day communication norms, citation practices reflect the goals, values, and assumptions of specific disciplines. Variations in values and priorities include the following:

Time and Recency

Notice how the publication date is included in the in-text citation in APA, while it’s omitted in MLA. This reflects the importance of recency in the sciences — the emphasis on the most up-to-date knowledge. In the humanities, on the other hand, while interpretations and values shift, or new information can come to light, time and recency are much less important — an analysis of Shakespeare written twenty years ago could be as relevant today as when it was written.

Authorship and Individuality

Even smaller differences can reflect distinctive philosophies about how knowledge is produced and why it’s important. For example, take the fact that MLA includes an author’s full first name, while APA only includes their first initial. This reflects the emphasis of the humanities, which generally use MLA, on authorship — highlighting the importance of individual thoughts, opinions, and interpretations.

Individual opinion or argument is much less important in the sciences, where knowledge tends to be seen more as something that’s “discovered,” rather than “interpreted.” Authorship in the sciences is also seen more as a collaborative activity — researchers often work and publish collectively, rather than treating their work as an expression of individuality or perspective. It also has the effect of concealing clues about the gender identity of the author, which might be helpful in reducing biases that could influence how we interpret or value research. At the same time, it also might make it more difficult for readers to imagine or analyze the author’s positionality or social identity, a fuller perception of which could be important for understanding the motivations and limitations of the researcher and their approach.

Language and Reality

Finally, these differences may also reflect foundational distinctions between the language ideologies [Chapter 13] of the sciences and humanities. Rhetorician Kenneth Burke argued that there are fundamental distinctions between what he called “scientistic” and “dramatistic” conceptions of language (Burke 44). In the former view, commonly held by the sciences, language is seen as something that describes the world, and the goal of language is to capture or explain an objective reality. In the latter view, commonly held by the humanities, language actively shapes our perceptions of the world, changing the meaning of objects in the world and our orientation to it.

So, according to Burke’s argument, these varying assumptions about the role and function of language determine how important we think language is. This can help us understand why language is more central to the humanities than it is to the sciences, and thus why the humanities spend more time thinking and talking about it.

Digging Deeper: From Chaos to Coherence

Andrew Gilbert and Randy Yerrick note that many scholars of science communication argue that “scientific work is achieved largely by building arguments to persuade or convince other scientists through competition; a process that forces documents and data toward particular outcomes for reasons other than pure rationality. In other words, the construction of a scientific argument entails covering up the confusing, random, and chaotic means that produced it so as to give the impression that it is an objective reflection of the world as it really exists” (69).

What do you think this means? What might be the benefits — and drawbacks — of communication norms that conceal the messy process of testing and discovery? Similarly, how could “competition” in the field produce both good and bad results?

Push Back: Critiques of Academic Communication

While these ideas about “good” writing and communication in academia are widely held and practiced, there has also been pushback to many of these norms. Even standards that seem universal across fields, and which have reasonable justifications, such as the demand for scholarly citations, have been challenged. Critics are questioning the power and influence granted to frequently-cited papers, questioning why some scholars get cited more than others. For example, Amber Lancaster and Carrie S. Tucker King argue that “Citations are ‘political acts’ in the sense that selecting whose scholarship to cite, and thus to promote, privileges some voices over others… Selecting whose voice to cite and promote reflects those relationships as well as the underlying authority and power structures of the publishing process…”(1).

While this suggests that backroom networks of friendship and influence might be influencing who gets cited, other scholars have identified clear patterns in citation inequity. They call out “citation injustice,” arguing that women and scholars of color have traditionally been underrepresented in citations — and continue to be so.

For example, a 2018 article in Inside Higher Ed [Website] summarized research that “confirmed what many have long suspected — that male authors tend to cite other men over women in their article bibliographies.” The study they cited also suggested that, perhaps more surprisingly, “such underlying biases can apply even in a journal with a majority of female authors, and may spread to papers co-authored by women with men…”

Further, racial biases have also been shown to impact who gets cited and how often. For example, in a 2018 study of citations in communication studies journals, Paula Chakravartty reported that “non-White scholars continue to be under-represented in publication rates, citation rates, and editorial positions…” (p. 254). In other words, this suggests that there’s a kind of negative feedback loop: if fewer scholars of color get cited, then they are less likely to earn an editorial position, which in turn means fewer people in a position of publishing power to support the work of scholars of color — and so the cycle continues.

Citation inequities are only one of the problems of “academic discourse.” As discussed in “The Hidden Language of Language” [Chapter 13], “standard English,” the kind of language typically taught in schools, tends to align with the home languages of white, middle- and upper-class students, making it easier for them to get good grades and write “correctly” according to that standard. Academic discourse, as a variant of “standard English,” carries the same problem — making it easier for people with race and class privilege to succeed in many academic fields.

Conclusion

Learning to write like a professor is a key part of learning to think like a professor. This includes benefits as well as drawbacks. As one history teacher puts it, learning to write like a historian “requires a change in thinking about history — from thinking of history as a subject in which one memorizes vast quantities of unrelated facts to a subject in which one critically considers historical sources or other people’s interpretations of the past as one crafts his or her own interpretation of the same events or people” (Monte-Sano, 296). In other words, these “rules” of communication help train our brains in habits of thinking that are critical to understanding the world in new and complex ways.

So, should we teach these “academic norms,” or not? Can you, as students, learn to write and communicate in these ways, but also learn to challenge and question them? Patricia Bizzell puts it this way:

In short, our dilemma is that we want to empower students to succeed in the dominant culture so that they can transform it from within; but we fear that if they do succeed, their thinking will be changed in such a way that they will no longer want to transform it (228).

Part of your work — and all our work — in analyzing academic discourse is to avoid this “brainwashing” and preserve the ability to think outside of — as well as within — these frameworks. We do this so that even when our thinking is “changed” by learning new ways of communicating, we can still evaluate the extent to which they make the world more open or closed; more just or unjust.

Whether you decide to conform to, or push back against, the norms of your discipline, it’s important for you to know what they are, what their purpose is, and why you’re choosing to — or not to — adhere to them. Because, whether you like it or not, those seemingly “neutral” or arbitrary rules for communication both reflect and shape your ideas about who can talk and what can be said. In his essay, “The Idea of Community in the Study of Writing,” Joseph Harris writes:

We write not as isolated individuals but as members of communities whose beliefs, concerns, and practices both instigate and constrain, at least in part, the sorts of things we can say. Our aims and intentions in writing are thus not merely personal [or] idiosyncratic, but reflective of the communities to which we belong (12).

As Harris suggests, understanding your major and understanding the way people in your major communicate are inextricably linked. At the same time, it’s important to maintain “critical distance” — an ability to see how writing and communication in your major could be otherwise, and what the consequences of other rules and norms might be.

Test Your Knowledge

Suggested Activities

- Identity reflection: How has your choice of major shaped your individual or community identity? Write a short paper or discuss the following in class: To what extent do you feel part of a “community” in relation to your major? To what extent do you feel your identity is related to your choice of major? Has your sense of identity or way of thinking shifted at all as you’ve pursued your major? Has the way that you see the world, or others, changed? What factors or experiences have made you feel “closer” or “farther” from your major?

- Create your own handbook: Imagine you are creating a handbook for writing in your major. Your audience is first-year students. You have to give them a bullet-pointed list of “dos” and “don’ts” for good writing or good communication. Feel free to draw on your own experience, interviews with professors, research, and GenAI (if your professor allows).

Further Reading and Resources

- Reading Games: Strategies for Reading Scholarly Sources

- Prof. Swales on Genre and English for Academic Purposes

- “You Can Learn to Write in General” in Bad Ideas About Writing

- “Writing Knowledge Transfers Easily” in Bad Ideas About Writing

- “Excellent Academic Writing Must Be Serious” in Bad Ideas About Writing

Works Cited

“Anatomy of a Scholarly Article.” NC State University Libraries, North Carolina State University, 8 May 2025, www.lib.ncsu.edu/tutorials/scholarly-articles/. Accessed 3 June 2025.

Bizzell, Patricia. Academic Discourse and Critical Consciousness. University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992. dokumen.pub/academic-discourse-and-critical-consciousness-1nbsped-9780822971559-9780822954859.html.

Burke, Kenneth. “Terministic Screens” in Language as Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature, and Method. University of California Press, 1966, pp. 44-62.

Chakravartty, Paula, et al. “#CommunicationSoWhite.” Journal of Communication, vol. 68, no. 2, Apr. 2018, pp. 254-66.

Donahue, Christian, and Jennifer Foster-Johnson. The Oxford Handbook of Academic Writing. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Downs, Doug, and Elizabeth Wardle. “You Can Learn to Write in General.” Bad Ideas About Writing, edited by Cheryl E. Ball and Drew M. Loewe, Digital Publishing Institute, 2017, https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Composition/Specialized_Composition/Bad_Ideas_About_Writing_(Ball_and_Loewe)/01%3A_Bad_Ideas_About_What_Good_Writing_is_…/1.05%3A_You_Can_Learn_to_Write_in_General.

Elbow, Peter. “Reflections on Academic Discourse: How It Relates to Freshmen and Colleagues.” College English, vol. 53, no. 2, Feb. 1991, pp. 135-55.

Harris, Joseph. “The Idea of Community in the Study of Writing.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 40, no. 1, Feb. 1989, pp. 11-22.

Kopelson, Kevin. “Excellent Academic Writing Must Be Serious.” Bad Ideas About Writing, edited by Cheryl E. Ball and Drew M. Loewe, Digital Publishing Institute, 2017, https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Composition/Specialized_Composition/Bad_Ideas_About_Writing_(Ball_and_Loewe)/05%3A_Bad_Ideas_About_Genres/5.01%3A_Excellent_Academic_Writing_Must_be_Serious.

Lancaster, Amber, and Carie S. Tucker King. “Empowerment through Authorship Inclusivity: Toward More Equitable and Socially Just Citation Practices.” Communication Design Quarterly, vol. 12, no. 4, Dec. 2024, pp. 1-15. SIGDOC.org, cdq.sigdoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/CDQ-Volume-12-Issue-4.pdf.

Monte‑Sano, Chauncey. “What Makes a Good History Essay? Assessing Historical Aspects of Argumentative Writing.” Social Education, vol. 76, no. 6, Nov.–Dec. 2012, pp. 294–298.

Pells, Rachel. “New Research Shows Extent of Gender Gap in Citations.” Inside Higher Ed, 16 Aug. 2018, www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/08/16/new-research-shows-extent-gender-gap-citations.

Reiff, Mary Jo, and Anis Bawarshi. “Writing Knowledge Transfers Easily.” Bad Ideas About Writing, edited by Cheryl E. Ball and Drew M. Loewe, Digital Publishing Institute, 2017, https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Composition/Specialized_Composition/Bad_Ideas_About_Writing_(Ball_and_Loewe)/01%3A_Bad_Ideas_About_What_Good_Writing_is_…/1.06%3A_Writing_Knowledge_Transfers_Easily.

Rosenberg, Karen. “Reading Games: Strategies for Reading Scholarly Sources.” The Ask: A More Beautiful Question, 2nd ed., edited by Kate L. Pantelides et al., MTSU Pressbooks Network, 2021, https://mtsu.pressbooks.pub/engl1020/chapter/reading-games-strategies-for-reading-scholarly-sources/.

Student Tips. “Essential Rules For Academic Writing | Student Tips.” YouTube, uploaded by Student Tips, Apr. 2022, youtu.be/6XtBnCr_cVk.

TESOLacademic. “Prof. Swales on Genre & English for Academic Purposes.” YouTube, 6 Jan. 2016, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W–C4AzvwiU.

westernmasswp. “Peter Elbow at WMWP.” YouTube, 23 Oct. 2013, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JezvZjc8oUQ.

Yerrick, Randy and Andrew Gilbert. “Constraining the discourse community: How science discourse perpetuates marginalization of underrepresented students,” Journal of Multicultural Discourses, vol. 6, no. 1, 2011, pp. 67-91. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17447143.2010.510909#d1e271

Zongker, Doug. “Chicken Chicken Chicken: Chicken Chicken.” Isotropic, University of Washington Department of Computer Science & Engineering, 21 May 2002, isotropic.org/papers/chicken.pdf.

Attributions

This chapter was written by Leigh Meredith.

Media Attributions

- Academic Discourse Community © Leigh Meredith, using ChatGPT is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Contrasting Models of Human Cognition © Anderson, Stephen P.; Fast, Karl, 2020. Figure It Out: Getting From Information to Understanding. New York: Rosenfeld Media. adapted by Flickr is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- ChickenChickenScreenShot

- APA vs MLA Citation © Leigh Meredith, using ChatGPT is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license