8 What Is a Discourse Community?

Overview

A discourse community is a group of people with a common goal or cause who work together using communication to advance their shared interests. Discourse communities can vary widely in their communication practices, including how they choose to share information and perspectives. The interplay between discourse communities and language attitudes demonstrates how communal values can shape perceptions of language use and its legitimacy. It addresses how different modalities — including written, spoken, visual, and digital forms — can be utilized within discourse communities to reflect the diverse ways members communicate and express their identities.

Over the course of this chapter, we’ll discuss how discourse communities facilitate the sharing of knowledge and influence attitudes toward language and communication practices. We will also examine the importance of discourse communities in shaping both individual identities and collective norms in a variety of contexts.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Define “discourse community”

- Identify the characteristics that comprise a discourse community

- Examine the relationship between language attitudes and discourse communities

- Reflect on how knowledge of discourse communities can improve your own communication

Discourse Communities: A Brief History

We all use different styles of communication at home, at work, and with our friends. During the 20th century, rhetoricians started thinking more deeply about this everyday variation. Many scholars credit Martin Nystrand with coining the term “discourse community” to describe the way that communication goals and practices are shared within specific groups. Other scholars built on Nystrand’s initial ideas; linguist John Swales [Website] popularized the term, and writing studies theorist Thomas Deans came up with the model of discourse communities that we refer to in this text. In this chapter, we will define and discuss various concepts related to discourse communities and how they work at school and in various public contexts. It’s important to note that, even though they share some characteristics, not all members of a discourse community will speak, read, write, listen, and view topics in exactly the same way.

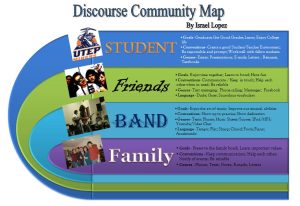

To recap, we are all part of multiple discourse communities. These communities can be tied to your major, your job, your friend groups, your family, or a shared interest.

Figure 8.1. Israel Lopez Discourse Community Map (Discourse_Community_Map_Accessible [New Tab])

“Rules” in a Discourse Community

Within discourse communities, there is usually a shared understanding of how members communicate with each other. It is important to note that there is no universal set of rules, and that preferences can vary widely between and even within discourse communities. But there are probably some common patterns in the ways that you communicate at work (for example), which are different than the ways you communicate at school or with your family.

How Do You Join a Discourse Community?

What it means to join or be part of a discourse community is understood differently by each community. Entering a discourse community can mean any number of things, from speaking in your native language or dialect to learning about a specific topic, or even contributing work toward a shared goal. Joining a discourse community can come naturally, but it doesn’t just require that you know the language or vocabulary of that group. You may also need to learn about the culture and context that a particular community exists in.

Figure 8.2. Discourse Community Criteria. This graphic outlines six key criteria that define a discourse community, including shared goals, communication mechanisms, participatory feedback, genre utilization, specialized vocabulary, and a level of expertise among members. (Discourse_Community_Criteria_Accessible [New Tab])

Thomas Deans offers an overlapping but simpler model for defining discourse communities, breaking the key criteria down into four broader categories: common knowledge, habits of interpretation, patterns of language use, and shared assumptions. Understanding each of these will help you grasp the complexity of discourse communities and give you the vocabulary to analyze them. This theoretical framework is hard to fully understand without concrete examples. Below, we’ll take a deeper look at these concepts, including real-world examples of each.

1. Common Knowledge in Discourse Communities

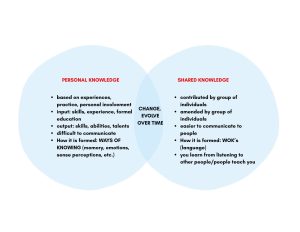

Common knowledge and information: Discourse communities assume and reproduce a shared set of knowledge, insights, and information related to a shared topic of interest. They also exchange and circulate old and new information through discussions, research, publications, or presentations.

Level of expertise and “thresholds” for membership: Members generally possess a certain level of knowledge and understanding of the community’s goals, communication methods, and topic(s) of interest. “Thresholds,” or the barriers to becoming a member of a community, vary from group to group. Many discourse communities — especially academic or professional ones — aim to educate newcomers or less experienced members. This can include formal teaching, workshops, or informal mentoring. In some groups, new members are just expected to “pick it up along the way,” developing understanding and knowledge as they spend more time in the group.

Encouraging innovation: Some discourse communities — especially in fields like technology or science — don’t just reproduce old knowledge, but also have the goal of fostering innovation. This might include developing new ideas, techniques, or products that advance the community’s objectives.

Listen: “Common Knowledge” (~2 mins)

Text Transcript of Common Knowledge (Accessible Word doc [New Tab])

Figure 8.3. Personal knowledge vs. shared knowledge (Personal_vs_Shared_Knowledge_AccessiblePersonal_vs_Shared_Knowledge_Accessible [New Tab])

Reflection

- Think about a discourse community that you are part of. What’s an example of something that’s “common knowledge” in your community, but relatively unknown outside of it? What rhetorical changes do you have to make when communicating with individuals outside vs. inside your community?

- Within your community, is shared knowledge categorized or preserved in any particular way? If so, how?

2. Habits of Interpretation in Discourse Communities

Promoting specific ways of understanding language and the world: Discourse communities often interpret language, and the world, in specific ways. They also promote particular practices and methodologies of interpretation. For example, academic communities may advocate for a particular research method or theoretical framework, or make judgement about what counts as good or bad evidence for a claim (for example, “qualitative” vs “quantitative” data). These modes of understanding are often linked to the specific values and goals of the community, which establish priorities (what’s important or unimportant about a set of information), and purposes (how the information will be used).

The same can be true for cultural communities, who may have a deeper and more precise understanding of the meaning of customs and traditions than those outside that community. In other words, a heritage food, like a tortilla, might be “interpreted” or made meaningful in different ways for those “inside” the cultural community than for those “outside” of it.

Watch: “Cultivating Identity: How Heritage Foods Connect Past, Present, & Future” (~8 mins)

Listen: “Habits of Interpretation” [Podcast] (~3 mins)

Text Transcript of Habit_of_Interpretation (Accessible Word doc [New Tab])

Reflection

- After seeing and hearing the examples above, how do you define “habits of interpretation”?

- How do you think generational differences influence the interpretation of a given form of communication?

- How can a community work to emphasize the importance of understanding context and assumptions within different discourse communities?

3. Patterns of Language Use in Discourse Communities

Specialized communication: Communities use different methods of communication (like emails, reports, or presentations) that are understood and used by members.

Intercommunication and feedback: Discourse communities have mechanisms for members to communicate and provide feedback to each other. The idea here is to foster a sense of belonging and shared purpose.

Establishing credibility and authority: Members of discourse communities often seek to establish themselves as credible voices or experts within a field. This is often achieved through publications, peer reviews, and active participation in discussions.

Developing shared terminology and communication styles: Discourse communities often develop a specific jargon or set of linguistic conventions that help members communicate complex ideas efficiently.

Watch: “What Is Jargon? – The Sociology Workshop” (~3 mins)

Building a collective identity: Discourse communities often work together to create a sense of belonging and shared identity. This fosters a deeper connection among members and helps strengthen the group’s ability to achieve its goals.

The video below examines how a collective identity strengthens the sense of belonging and shared purpose within a community.

Watch: “Belonging in Community” (~4 mins)

Listen: “Patterns of Language Use” [Podcast] (~2 mins)

Text transcript of Patterns_of_Language (Accessible Word doc [New Tab])

Reflection

Think about a discourse community that you are part of. How distinct is the language used in that discourse community? How does that language build a collective identity while maintaining credibility with outsiders?

4. Shared Assumptions in Discourse Communities

Shared assumptions: Shared assumptions in a discourse community refer to the foundational goals, beliefs, values, and understandings that individuals hold in common. These assumptions influence how members communicate and interact within a group. They also impact the knowledge, viewpoints, and blind spots of a given community.

Watch: “Edgar Schein’s Culture Model Explained with Example” (~10 mins)

Listen: “Shared Assumptions” (~1 min)

Text transcript of Shared_Assumptions (Accessible Word doc [New Tab])

Reflection

Think about a specific discourse community you are part of. Then, answer the following questions about it:

- Why are shared assumptions important to your discourse community?

- What are some of the shared assumptions of that community, and what purpose do they hold?

- In what ways do you believe that shared assumptions influence the way you communicate and interact within the group?

Discourse Communities and Change

Discourse communities aren’t static — the “rules” and norms that they follow change over time. These changes can be prompted by shifts in the larger culture — for example, many professional discourse norms in the U.S. have become more casual as norms in the larger culture have done the same. New technologies also prompt changes in groups’ communication channels — like how many advocacy groups have adopted social media to spread their messages. They can also be motivated by changes in the goals of the discourse community. For example, a shift from internal knowledge sharing to public outreach might require adapting a community’s language to be more accessible and understandable to a broader audience.

Changes can also be prompted internally — sometimes by members who are deliberately advocating for communication in their groups to be more inclusive or accessible.

Let’s take a closer look at how members negotiate language norms and practices within a discourse community. In particular, we’ll look at how discourse communities change over time. Tremain notes that, because a community’s communication style may change, members must learn to negotiate the differences and expectations of their own discourse through “translanguaging” and “code-meshing.” In the following reading, you will develop an understanding of what this may look like in your own discourse community.

Watch: “What is translanguaging, really?” (~2 mins)

Activity

Now, take some time to brainstorm your ideal discourse community below:

Further Reading and Resources

Works Cited

“Belonging in Community.” YouTube, www.youtube.com/watch?v=E0qoIh84FX0. 21 Jan. 2022.

“Edgar Schein’s Culture Model Explained with Example.” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HM89E6ltVOg. 1 Oct. 2022.

Crisfield. “What Is Translanguaging, Really?” YouTube, 16 May 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=iNOtmn2UTzI.

“Discourse Communities.” YouTube, Writing FIU, 6 Aug. 2019, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wRFjwnziJp8.

Garcia, Melisa. “Personal Knowledge vs. Shared Knowledge.”

Lopez, Israel. “Discourse Community Map.” Ilópez7english1311, 21 Sept. 2017, ilopez7english1311.blogspot.com/p/discourse-community-map-response.html.

Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area. “Cultivating Identity: How Heritage Foods Connect Past, Present, & Future.” YouTube, 5 May 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=AXXH6ZlLAis. Accessed 31 Mar. 2025.

The Sociology Workshop. “What Is Jargon? – the Sociology Workshop.” YouTube, 24 June 2025, www.youtube.com/watch?v=_EhWJcgnERc. Accessed 25 July 2025.

“What Can I Add to the Discourse Community? How Writers Use Code Meshing and Translanguaging to Negotiate Discourse – Writing Spaces.” Parlormultimedia.com, 2025, parlormultimedia.com/writingspaces/what-can-i-add-to-the-disourse-community-how-writers-use-code-meshing-and-translanguaging-to-negotiate-discourse/.

Wolf, Tammy, and Megan Barnes. “A Discourse Community.” English 1101, New Mexico Open Educational Resources“, nmoer.pressbooks.pub/english1101/chapter/chapter-1-2-discourse-communities-and-conventions-mytext-cnm/.

Attributions

This chapter was written and remixed by Melisa Garcia.

This chapter was adapted from “Chapter 2: Discourse Communities and Conventions” by Tammy Wolf and Megan Barnes, and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Media Attributions

- dc map (1)

- Blue-Brushstroke-List-Maker-Advocacy-Interactive-Instagram-Story

- Doc3.pdf – 1