13 Public Genres

Overview

In this chapter, you will start to identify genres in public communication, shared cultural narratives, and professional workplace communication. You’ll learn to recognize and analyze the shared characteristics of these genres and the rhetorical situations that call them forth.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Identify examples of genres used in public communication

- Evaluate the impact of genre conventions on audience reception and interpretation within art, news, medical, and social media contexts

- Critically assess the role of social media platforms as both genre creators and platforms for genre expression

- Develop strategies for creating engaging and informative content tailored to specific genres

Recognizing Public Communication Genres

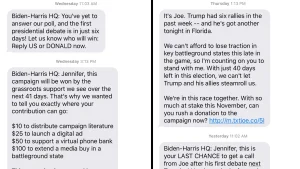

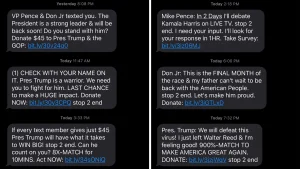

If you’re a registered voter in the United States, you are probably used to getting political ads around election time. Candidates attempt to rally support by sending out mass communications to people who are signed up for various mailing lists or who have donated to certain causes. These messages are often sent via email or text message, and they tend to look like the following examples:

Figure 13.1. A compilation of screenshots of text messages sent by the Joe Biden campaign to Jennifer Stromer-Galley, a professor at Syracuse University (Biden_Harris_Texts_(Accessible Word doc) [New Tab])

Figure 13.2. A compilation of screenshots of text messages from various political campaigns (Political_Texts_Composite_(Accessible Word doc) [New Tab])

Figure 13.3. A compilation of screenshots of text messages sent by President Trump’s campaign to Jennifer Stromer-Galley, a professor at Syracuse University (Trump_Campaign_Texts_(Accessible Word doc) [New Tab])

Do these messages look familiar?

Even though they were sent to promote two very different candidates, these messages share many similarities that signal that they belong to a particular genre of communication. Let’s review the four S’s of genre to analyze how these messages work.

- Situation: These messages are from a candidate or campaign (writer) to registered voters (audience), alerting them to the upcoming election (exigence).

- Substance: Each message provides a brief update on a campaign’s progress or challenges it is facing.

- Style: The messages are intended to give the impression that Joe Biden, Nancy Pelosi, or Donald Trump, Jr., is directly messaging you; they often address the audience by name and use language like “us” and “we” to create a sense of identification, while also maintaining a tone of urgency.

- Social action: The goal of these messages is to rally support, usually in the form of donations.

Reflection

Take a moment to answer the following questions about the political messages we’ve just reviewed:

- What details stand out about how these messages are constructed?

- What other examples of political messaging have you seen, and how do they either fit or deviate from these norms?

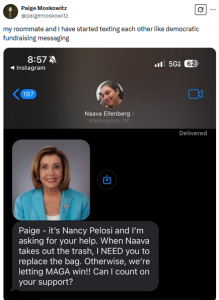

This genre of political communication has become so ubiquitous over the last few years that it’s given rise to parodies:

Figure 13.4. From social media site X (formerly Twitter) (Pelosi_Parody_Text_(Accessible Word doc) [New Tab])

How does this joke text message use the conventions of the political fundraising text message genre?

Narrative Genres

In “What Is Genre?” [Chapter 15], we discussed some of the recurring features of movies such as Black Panther or Wonder Woman that signal to the audience that you are watching a superhero movie: similar character roles, plot structures, and formal elements such as how the films look or sound. These elements can also be used to recognize other narrative or artistic genres, including movies, television, novels, music, and video games. In turn, this enables us to distinguish one genre from another (e.g., classifying a TV series as “true crime” vs. “horror”), talk about how an artifact utilizes or breaks the conventions of the genre (e.g., is Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter a country music album?), or even identify new genres that are starting to become popular (e.g., what is “dark academia” or “cozy fantasy,” anyway?).

But the study of genre isn’t just confined to art or fictional narratives; we can also think about how real-life figures and events are presented to us. Walter Fisher, a scholar and professor of communication, claimed that human beings are homo narrans — that what makes us unique from other animals is our capacity to tell stories and understand our experiences through narrative. Stories are used as points of reference all the time: if we say that a celebrity has been a real ugly duckling, we know that the celebrity might have started off unappreciated or disregarded, but is now undeniably popular. These narratives are shared cultural points of reference that can orient our understanding of the people or events involved.

Cultural Narratives

Here is an incomplete list of common narratives that might be referenced when talking about real-life people or events:

- Cinderella story — a story where an underdog rises up to accomplish more than was expected of them

- Goldilocks principle — the tendency to seek something that is not too far toward one extreme or another, but is “just right”

- The American dream — the belief that all people in the United States have the freedom and opportunity to “succeed” and attain a better life

- Madonna-whore complex — the distorted lens through which women are viewed and valued by patriarchal society based on their sexual availability; under this framework, women who exercise sexual autonomy are considered “debased” and less deserving of men’s attention or protection (Bareket et al.)

Can you identify any events or people who fit into these cultural narratives? What other narratives do we hear commonly referenced in current events or popular culture?

Digital Genres

We already know that the media we use influence how we communicate (see “Media Matters: Oral, Print, and Digital Rhetorics” [Chapter 6] and “Understanding the Five Modes of Multimodality” [Chapter 7] to review). The rise of digital media and the Internet has created new opportunities for communication. For example, in a traditional classroom environment, you’d probably raise your hand to contribute to a discussion; in an online class that’s held over Zoom, however, it can often be more effective to write your question or comment in the chat.

Medium and genre are not the same thing, however: media are channels of communication, whereas genres are specific, recurring types of communication. However, these boundaries start to blur when we talk about online spaces, such as social media: the style and substance of an Instagram post (usually image- or video-based) are clearly different from those of a LinkedIn post (primarily text-based). So, within the category of “social media posts,” Instagram and LinkedIn might each constitute their own genre of communication. However, if we focus on a particular platform, we can distinguish between genres of posts (e.g., “Get Ready With Me” videos, explainer slides, or selfies).

New platforms and technologies give rise to new ways of communicating, and our ability to respond to recurrent rhetorical situations in similar ways creates digital genres of communication. Take the genre of true crime podcasts, for example. While people have long reported on violent crime through traditional print and television news media, the 2014 podcast Serial marked a major change in how true crime stories are told.

Podcasts are an ideal format for audio storytelling because they can be so immersive; as we listen to the narrators or people featured on these podcasts, we start to feel like we really know them, as opposed to learning about a crime on television or in a book. Further, the serialized structure of podcasts allows the story to be told across multiple episodes, encouraging the listener to keep coming back for more. Serial took advantage of these features of the podcasting medium, while also highlighting larger issues behind the case it covered, such as how the race and religion of the defendant in a murder trial affected his treatment by the criminal justice system.

Following the success of Serial, many more true crime podcasts have been created and are widely listened to. These podcasts don’t just address topics similar to those covered in Serial; they also take a similar approach by focusing on those who are accused (such as the podcast Criminal) and a similar tone to Serial’s host, Sarah Koenig (even in the case of comedy true crime podcasts such as Who Shat On the Floor At My Wedding?). Some even take a more irreverent approach as a way of distinguishing themselves from Serial (such as the comedy true crime podcast My Favorite Murder).

Celebrity Apology Videos

Once upon a time, if a celebrity needed to address a controversy or issue a public apology, they’d speak to a journalist or issue a statement that would be published in a newspaper or magazine. With social media, however, the celebrity can now speak directly to their followers. While this format is new, the conventions for this genre have already started to become standardized. We have a sense of when a public apology is warranted and to whom it is addressed (situation). We also expect the apology to sound a certain way or to address particular issues (substance); the apology is often issued informally, generally in the form of a screenshot of text from a smartphone or a video upload to a platform like TikTok, YouTube, or Instagram (style). Ultimately, the apology aims to explain what happened, hopefully earning the audience’s forgiveness and regaining their trust (social action).

Interestingly, it’s not uncommon for apology videos to spark further criticism. Here are some examples of controversial apologies from celebrities:

Watch: “‘My behavior was unacceptable.’ Will Smith addresses Oscars slap, apologizes to Chris Rock” (~6 mins)

Watch: “So Sorry.” (~2 mins)

Watch: “Drew Barrymore slammed for now-deleted apology video” (~2 mins)

Watch: “hi.” (~10 mins)

What are some common phrases or tactics that celebrities use to explain their actions and apologize for their mistakes? What similarities in composition or presentation do you see?

Pick one of these videos (or choose your own celebrity apology video) and research it further. What happened to prompt this video? What was the public response? What seems to make an effective or ineffective apology?

Because the Internet and social media are so strongly driven by algorithms and user trends, new genres of digital communication come into being or fall out of favor all the time.

Professional Communication Genres

Communication is an essential skill in the professional world, whether you’re working with colleagues, your boss, or clients. These situations also recur, which creates the need for standardized professional communication genres. Below are some resources on common types of business writing, including their purpose, structure, and advice for crafting effective communication.

Activity: Create a Social Media Post

Choose a prompt and a genre from the lists below. Then, create a short social media post in that format.

Prompts:

- What did you have for breakfast?

- What is one concept from your major that everyone should understand?

- Which is the best bathroom on campus, and why?

- What was your most memorable birthday?

- What is one class that every student should take in college?

- Why should we all watch your favorite television show?

- What fictional animal would make the best pet?

- How do you develop a new habit?

- What is the best cheap activity to do in the city?

- Another prompt of your choice

Genres:

- True crime podcast

- Instagram infographic

- Lifestyle vlog

- TikTok dance

- LinkedIn post

- Yelp review

- Tier list

- Alignment chart

- Reddit post

- Another genre of your choice

Further Reading and Resources

- “Navigating Genres” [Website]

- “Last to Be Written, First to Be Read: Writing Memos, Abstracts and Executive Summaries” [Website]

- “Make Your ‘Move’: Writing in Genres” [Website]

Works Cited

ABC7. “Video: ‘My Behavior was unacceptable.’ Will Smith addresses Oscars slap, apologizes to Chris Rock.” YouTube, 29 July 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7XyNqHalkMw.

Ballinger, Colleen. “hi.” YouTube, 28 June 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ceKMnyMYIMo.

Bareket, Orly; Kahalon, Rotem; Shnabel, Nurit; Glick, Peter. “The Madonna-Whore Dichotomy: Men Who Perceive Women’s Nurturance and Sexuality as Mutually Exclusive Endorse Patriarchy and Show Lower Relationship Satisfaction”. Sex Roles. vol. 79, Feb. 2018, pp. 519–532

Dirk, Kerry. “Navigating Genres.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 1, edited by Charley Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky, Parlor Press, 2010, parlormultimedia.com/writingspaces/past-volumes/navigating-genres/. Accessed 22 July 2025.

Fisher, Walter. “Narration as a human communication paradigm: The case of public moral argument.” Communication Monographs, vol. 51, no. 1, 1984, pp. 347-367.

Ilyasova, K. Alex. “Last to Be Written, First to Be Read: Writing Memos, Abstracts and Executive Summaries.” Technical Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 6, edited by Kirk St.Amant and Pavel Zemliansky, Parlor Press, 2024, parlormultimedia.com/writingspaces/past-volumes/last-to-be-written-first-to-be-read-writing-memos-abstracts-and-executive-summaries/. Accessed 22 July 2025.

Jacobson, Brad, et al. “Make Your ‘Move’: Writing in Genres.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 4, edited by Dana Driscoll et al., Parlor Press, 2022, parlormultimedia.com/writingspaces/make-your-move-writing-in-genres/. Accessed 22 July 2025.

Paul, Logan. “So Sorry.” YouTube, 2 Jan. 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QwZT7T-TXT0.

The Independent. “Drew Barrymore slammed for now-deleted apology video” YouTube, 16 Sept., 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tfpr0CLBGTA.

Attributions

This chapter was written and remixed by Phil Choong.

Media Attributions

- Biden-Harris HQ texts © Jennifer Stromer-Galley

- Political text messages

- Trump texts © Jennifer Stromer-Galley

- my roommate and I have started texting each other like democratic fundraising messaging © Paige Moskowitz