Chapter 19. Development and Inheritance

19.2 Embryonic Development

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Distinguish the stages of embryonic development that occur before implantation

- Describe the process of implantation

- List and describe four embryonic membranes

- Explain gastrulation

- Describe how the placenta is formed and identify its functions

- Explain how an embryo transforms from a flat disc of cells into a three-dimensional shape resembling a human

- Summarize the process of organogenesis

Throughout this chapter, we will express embryonic and fetal ages in terms of weeks from fertilization, commonly called conception. The period of time required for full development of a fetus in utero is referred to as gestation (“gestare” meaning “to carry” or “to bear”). It can be subdivided into distinct gestational periods. The first 2 weeks of prenatal development are referred to as the pre-embryonic stage. A developing human is referred to as an embryo during weeks 3 to 8, and a fetus from the ninth week of gestation until birth. In this section, we’ll cover the pre-embryonic and embryonic stages of development, which are characterized by cell division, migration, and differentiation. By the end of the embryonic period, all of the organ systems are structured in rudimentary form, although the organs themselves are either nonfunctional or only semifunctional.

Pre-Implantation Embryonic Development

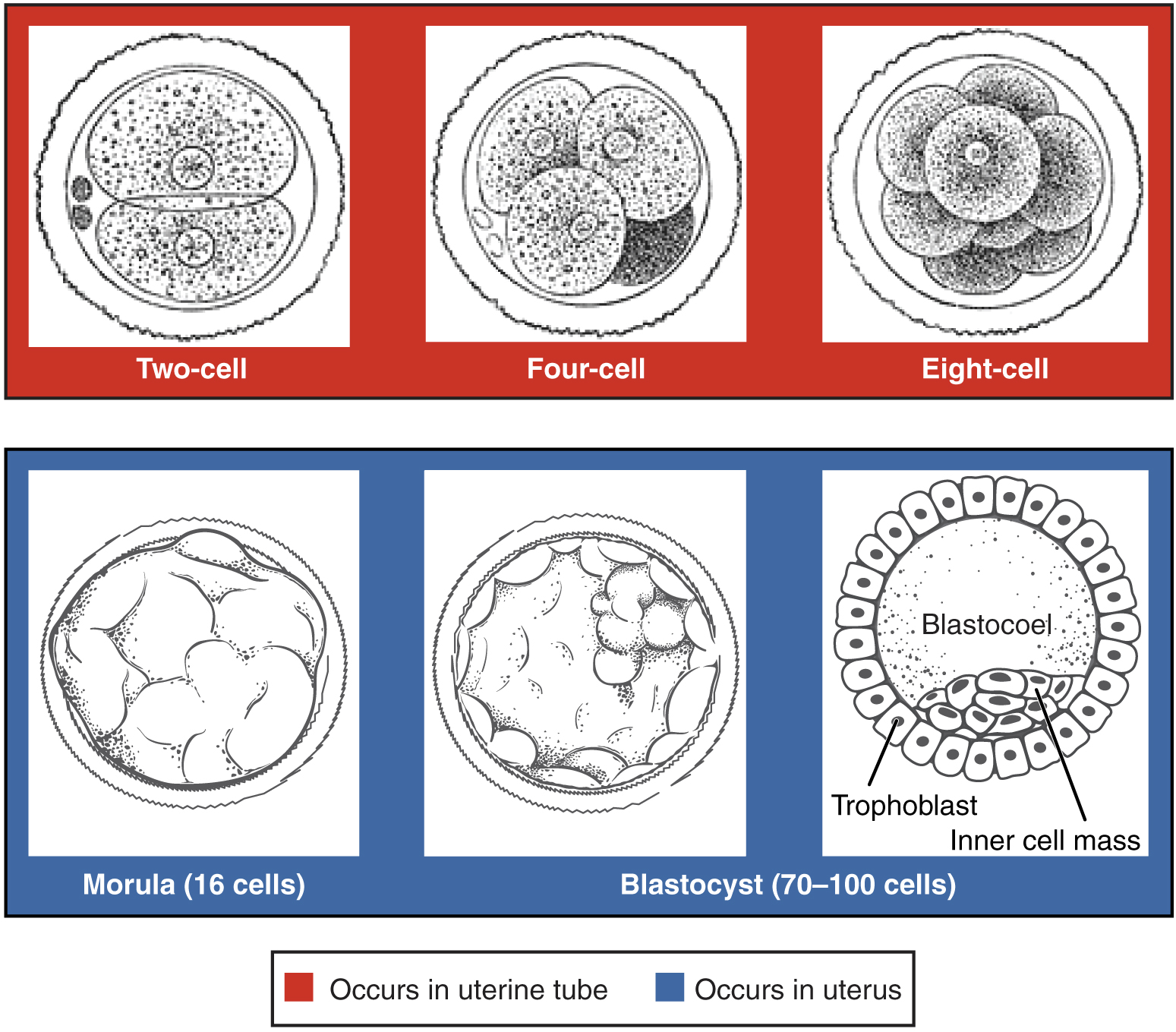

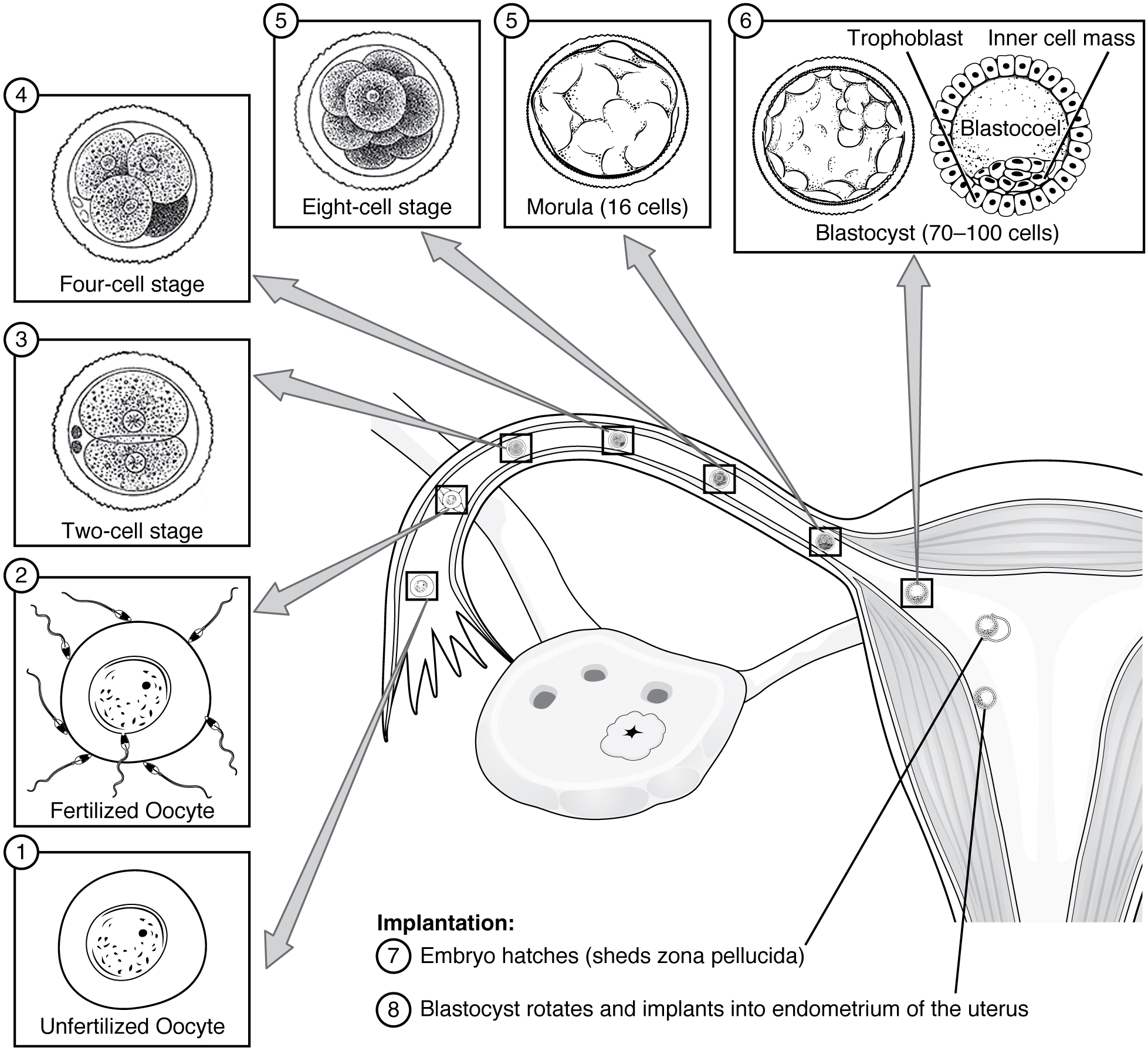

Following fertilization, the zygote and its associated membranes, together referred to as the conceptus, continue to be projected toward the uterus by peristalsis and beating cilia. During its journey to the uterus, the zygote undergoes five or six rapid mitotic cell divisions. Although each cleavage results in more cells, it does not increase the total volume of the conceptus (Figure 19.2.1). Each daughter cell produced by cleavage is called a blastomere (“blastos” meaning “germ,” in the sense of a seed or sprout).

Approximately 3 days after fertilization, a 16-cell conceptus reaches the uterus. The cells that had been loosely grouped are now compacted and look more like a solid mass. The name given to this structure is the morula (“morula” meaning “little mulberry”). Once inside the uterus, the conceptus floats freely for several more days. It continues to divide, creating a ball of approximately 100 cells, and consuming nutritive endometrial secretions called uterine milk while the uterine lining thickens. The ball of now tightly bound cells starts to secrete fluid and organize themselves around a fluid-filled cavity, the blastocoel. At this developmental stage, the conceptus is referred to as a blastocyst. Within this structure, a group of cells forms into an inner cell mass, which is fated to become the embryo. The cells that form the outer shell are called trophoblasts (“trophe” meaning “to feed” or “to nourish”). These cells will develop into the chorionic sac and the fetal portion of the placenta (the organ of nutrient, waste, and gas exchange between mother and the developing offspring).

The inner mass of embryonic cells is totipotent during this stage, meaning that each cell has the potential to differentiate into any cell type in the human body. Totipotency lasts for only a few days before the cells’ fates are set as being the precursors to a specific lineage of cells.

As the blastocyst forms, the trophoblast excretes enzymes that begin to degrade the zona pellucida. In a process called “hatching,” the conceptus breaks free of the zona pellucida in preparation for implantation.

Implantation

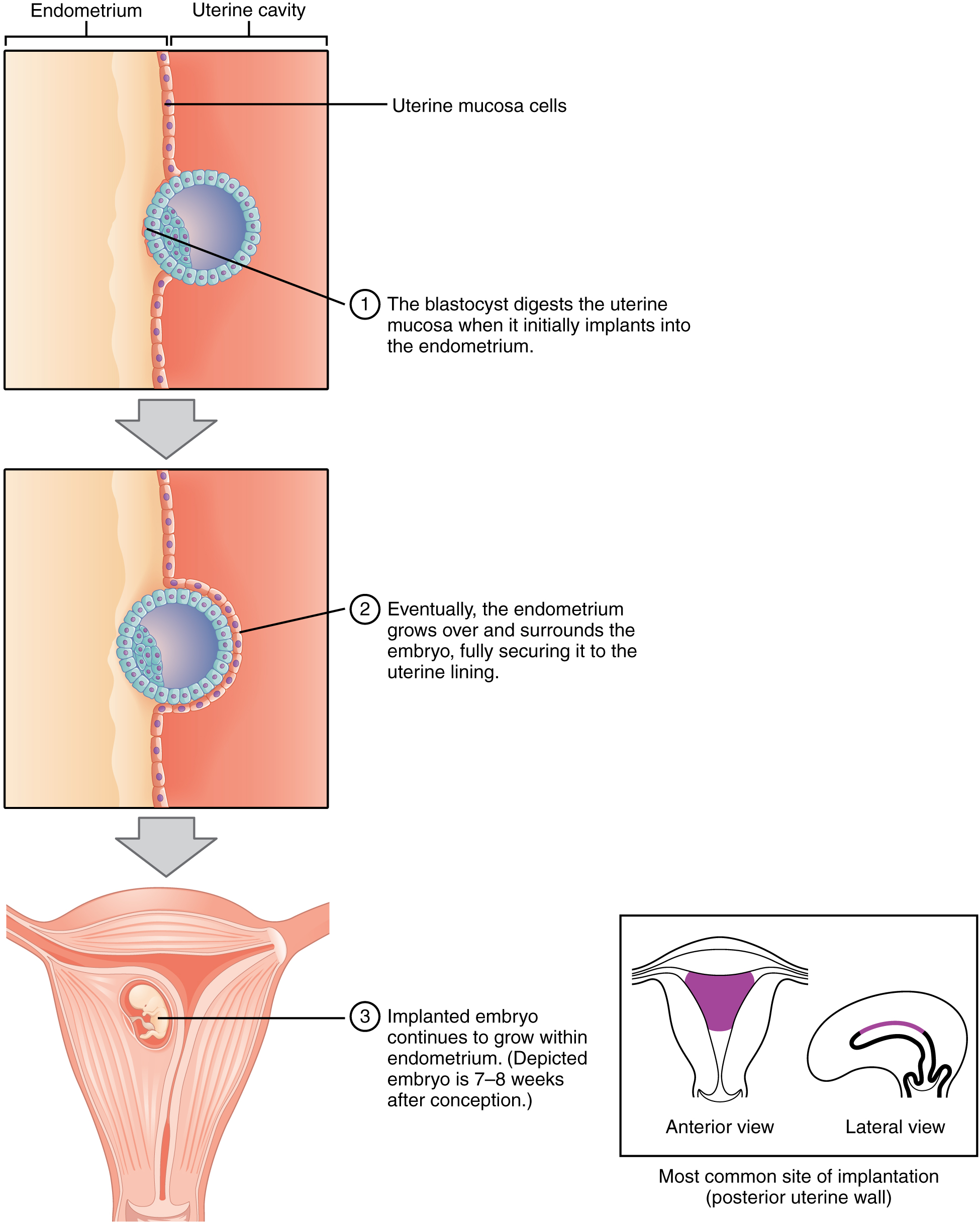

At the end of the first week, the blastocyst comes in contact with the uterine wall and adheres to it, embedding itself in the uterine lining via the trophoblast cells. Thus begins the process of implantation, which signals the end of the pre-embryonic stage of development (Figure 19.2.2). Implantation can be accompanied by minor bleeding. The blastocyst typically implants in the fundus of the uterus or on the posterior wall. However, if the endometrium is not fully developed and ready to receive the blastocyst, the blastocyst will detach and find a better spot. A significant percentage (50% to 75%) of blastocysts fail to implant; when this occurs, the blastocyst is shed with the endometrium during menses. The high rate of implantation failure is one reason why pregnancy typically requires several ovulation cycles to achieve.

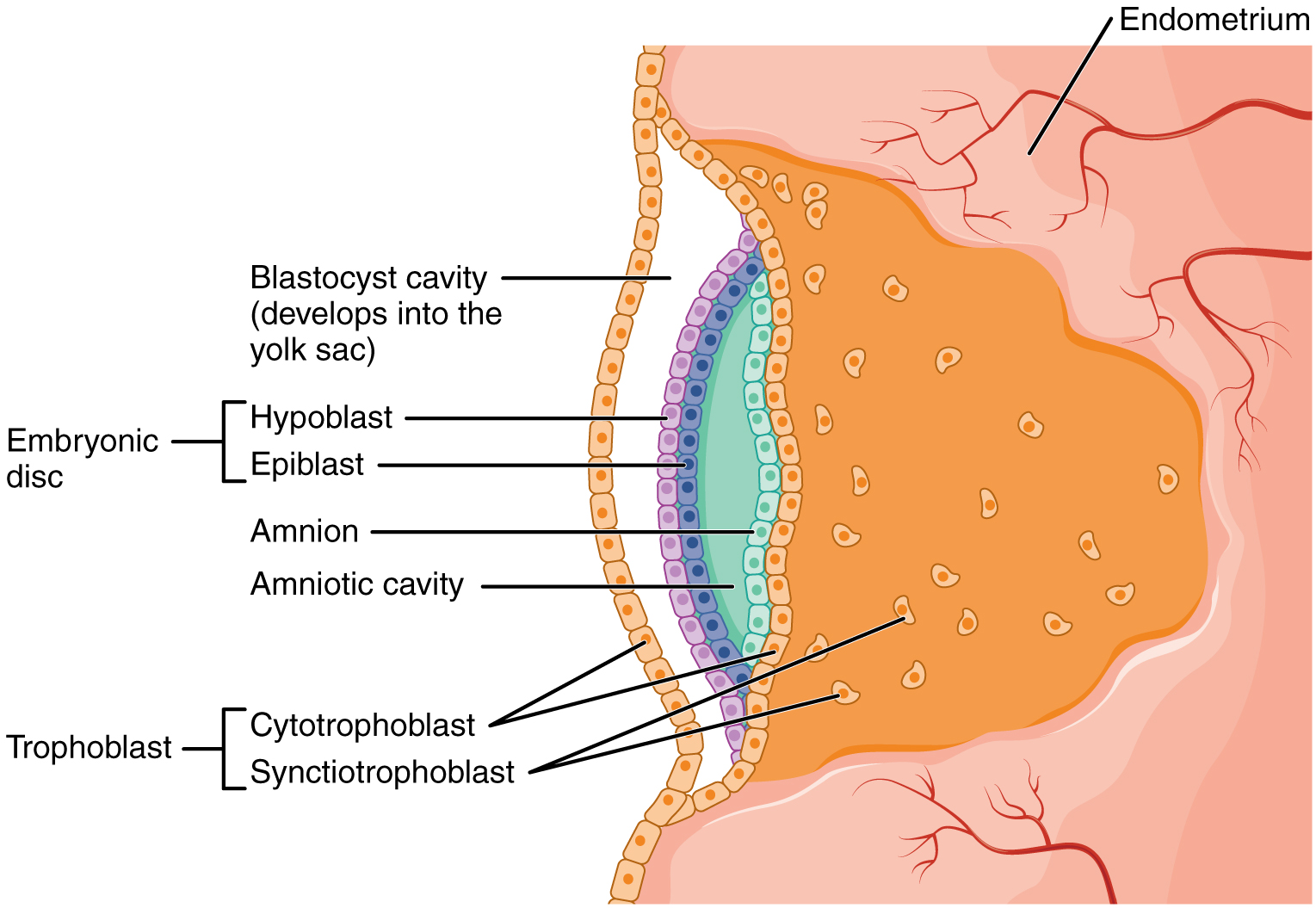

When implantation succeeds and the blastocyst adheres to the endometrium, the superficial cells of the trophoblast fuse with each other, forming the syncytiotrophoblast, a multinucleated body that digests endometrial cells to firmly secure the blastocyst to the uterine wall. In response, the uterine mucosa rebuilds itself and envelops the blastocyst (Figure 19.2.3). The trophoblast secretes human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), a hormone that directs the corpus luteum to survive, enlarge, and continue producing progesterone and estrogen to suppress menses. These functions of hCG are necessary for creating an environment suitable for the developing embryo. As a result of this increased production, hCG accumulates in the maternal bloodstream and is excreted in the urine. Implantation is complete by the middle of the second week. Just a few days after implantation, the trophoblast has secreted enough hCG for an at-home urine pregnancy test to give a positive result.

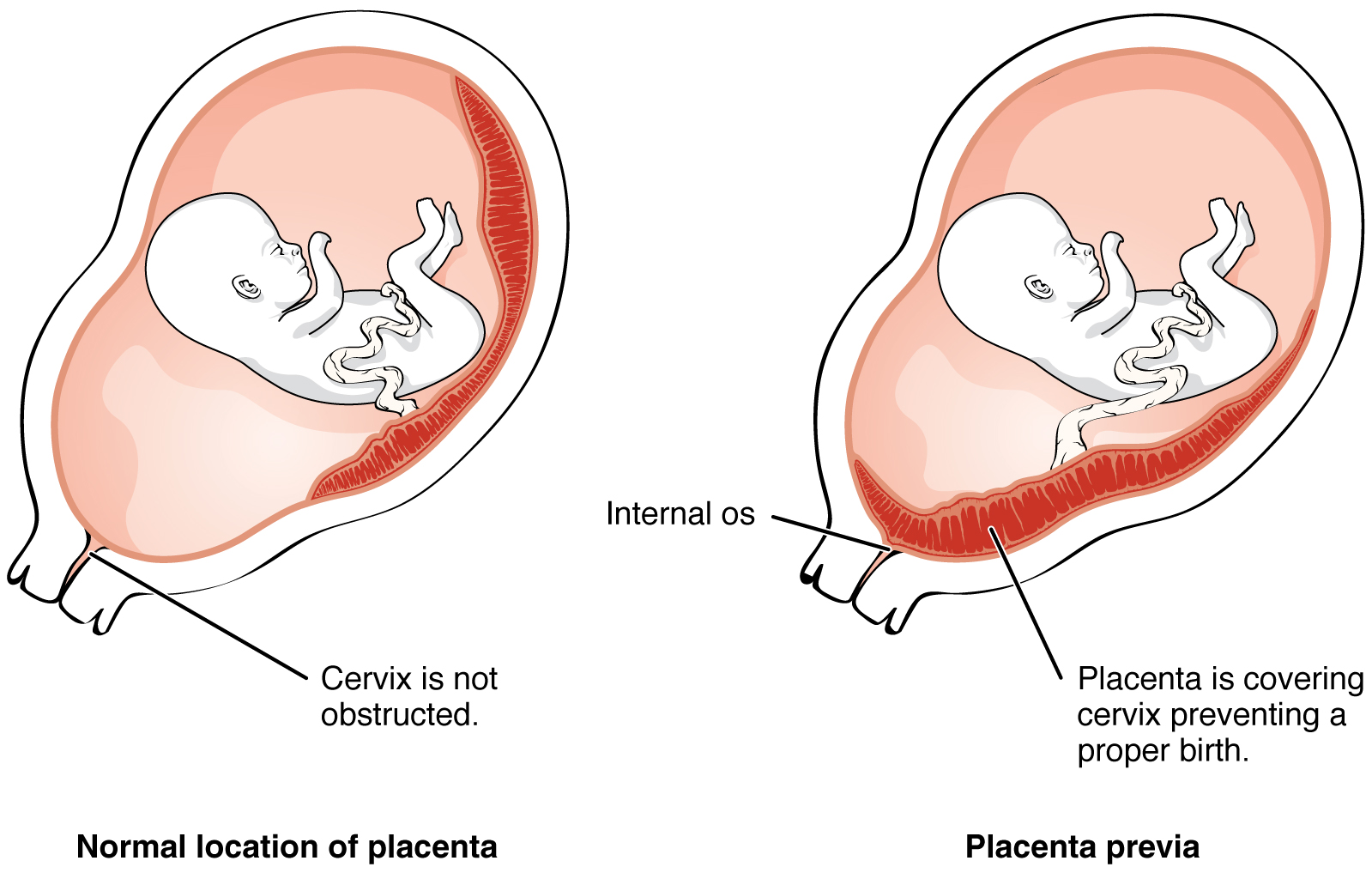

Most of the time an embryo implants within the body of the uterus in a location that can support growth and development. However, in 1% to 2% of cases, the embryo implants either outside the uterus (an ectopic pregnancy) or in a region of uterus that can create complications for the pregnancy. If the embryo implants in the inferior portion of the uterus, the placenta can potentially grow over the opening of the cervix, a condition call placenta previa.

Ectopic Pregnancies

In the vast majority of ectopic pregnancies, the embryo does not complete its journey to the uterus and implants in the uterine tube, referred to as a tubal pregnancy. However, there are also ovarian ectopic pregnancies (in which the egg never left the ovary) and abdominal ectopic pregnancies (in which an egg was “lost” to the abdominal cavity during the transfer from ovary to uterine tube, or in which an embryo from a tubal pregnancy re-implanted in the abdomen). Once in the abdominal cavity, an embryo can implant into any well-vascularized structure—the rectouterine cavity (Douglas’s pouch), the mesentery of the intestines, and the greater omentum are some common sites.

Tubal pregnancies can be caused by scar tissue within the tube following a sexually transmitted bacterial infection. The scar tissue impedes the progress of the embryo into the uterus—in some cases “snagging” the embryo and, in other cases, blocking the tube completely. Approximately one half of tubal pregnancies resolve spontaneously. Implantation in a uterine tube causes bleeding, which appears to stimulate smooth muscle contractions and expulsion of the embryo. In the remaining cases, medical or surgical intervention is necessary. If an ectopic pregnancy is detected early, the embryo’s development can be arrested by the administration of the cytotoxic drug methotrexate, which inhibits the metabolism of folic acid. If diagnosis is late and the uterine tube is already ruptured, surgical repair is essential.

Even if the embryo has successfully found its way to the uterus, it does not always implant in an optimal location (the fundus or the posterior wall of the uterus). Placenta previa can result if an embryo implants close to the internal os of the uterus (the internal opening of the cervix). As the fetus grows, the placenta can partially or completely cover the opening of the cervix (Figure 19.2.4). Although it occurs in only 0.5% of pregnancies, placenta previa is the leading cause of antepartum hemorrhage (profuse vaginal bleeding after week 24 of pregnancy but prior to childbirth).

Embryonic Membranes

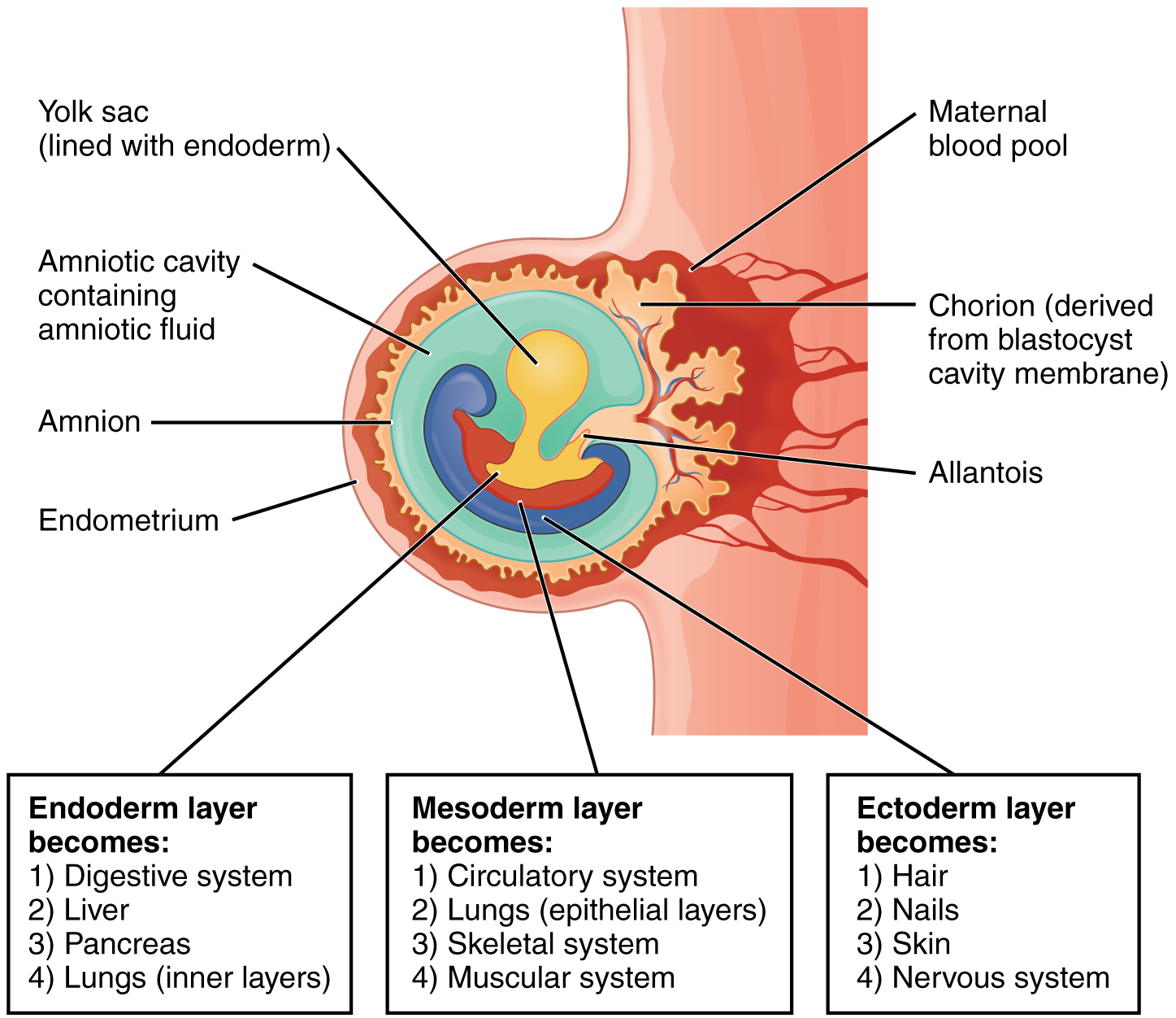

During the second week of development, with the embryo implanted in the uterus, cells within the blastocyst start to organize into layers. Some grow to form the extra-embryonic membranes needed to support and protect the growing embryo: the amnion, the yolk sac, the allantois, and the chorion.

At the beginning of the second week, the cells of the inner cell mass form into a two-layered disc of embryonic cells, and a space—the amniotic cavity—opens up between it and the trophoblast (Figure 19.2.5). Cells from the upper layer of the disc (the epiblast) extend around the amniotic cavity, creating a membranous sac that forms into the amnion by the end of the second week. The amnion fills with amniotic fluid and eventually grows to surround the embryo. Early in development, amniotic fluid consists almost entirely of a filtrate of maternal plasma, but as the kidneys of the fetus begin to function at approximately the eighth week, they add urine to the volume of amniotic fluid. Floating within the amniotic fluid, the embryo—and later, the fetus—is protected from trauma and rapid temperature changes. It can move freely within the fluid and can prepare for swallowing and breathing out of the uterus.

On the ventral side of the embryonic disc, opposite the amnion, cells in the lower layer of the embryonic disk (the hypoblast) extend into the blastocyst cavity and form a yolk sac. The yolk sac supplies some nutrients absorbed from the trophoblast and also provides primitive blood circulation to the developing embryo for the second and third week of development. When the placenta takes over nourishing the embryo at approximately week 4, the yolk sac has been greatly reduced in size and its main function is to serve as the source of blood cells and germ cells (cells that will give rise to gametes). During week 3, a finger-like outpocketing of the yolk sac develops into the allantois, a primitive excretory duct of the embryo that will become part of the urinary bladder. Together, the stalks of the yolk sac and allantois establish the outer structure of the umbilical cord.

The last of the extra-embryonic membranes is the chorion, which is the one membrane that surrounds all others. The development of the chorion will be discussed in more detail shortly, as it relates to the growth and development of the placenta.

Embryogenesis

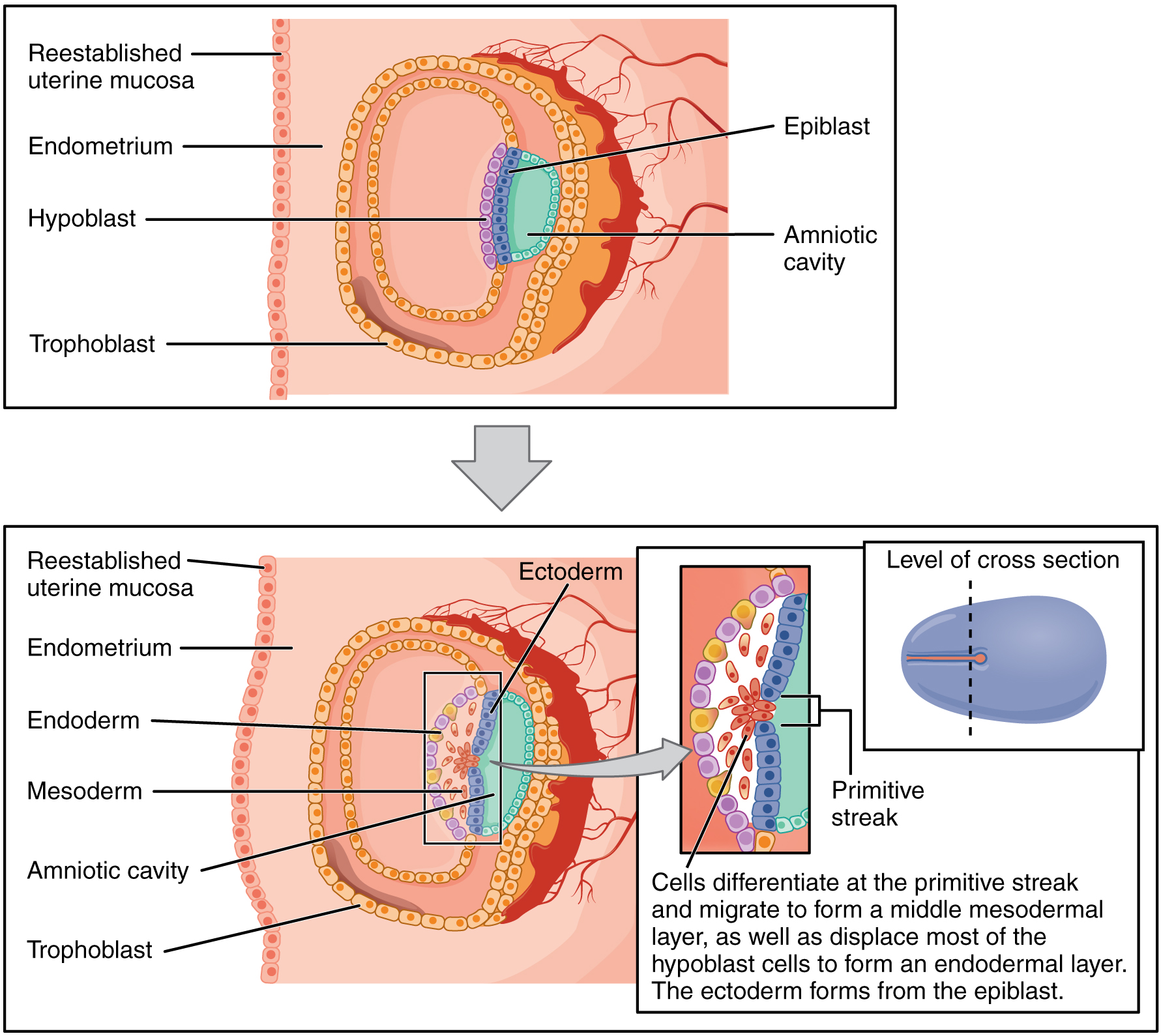

As the third week of development begins, the two-layered disc of cells becomes a three-layered disc through the process of gastrulation, during which the cells transition from totipotency to multipotency. The embryo, which takes the shape of an oval-shaped disc, forms an indentation called the primitive streak along the dorsal surface of the epiblast. A node at the caudal or “tail” end of the primitive streak emits growth factors that direct cells to multiply and migrate. Cells migrate toward and through the primitive streak and then move laterally to create two new layers of cells. The first layer is the endoderm, a sheet of cells that displaces the hypoblast and lies adjacent to the yolk sac. The second layer of cells fills in as the middle layer, or mesoderm. The cells of the epiblast that remain (not having migrated through the primitive streak) become the ectoderm (Figure 19.2.6).

Each of these germ layers will develop into specific structures in the embryo. Whereas the ectoderm and endoderm form tightly connected epithelial sheets, the mesodermal cells are less organized and exist as a loosely connected cell community. The ectoderm gives rise to cell lineages that differentiate to become the central and peripheral nervous systems, sensory organs, epidermis, hair, and nails. Mesodermal cells ultimately become the skeleton, muscles, connective tissue, heart, blood vessels, and kidneys. The endoderm goes on to form the epithelial lining of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and pancreas, as well as the lungs (Figure 19.2.7).

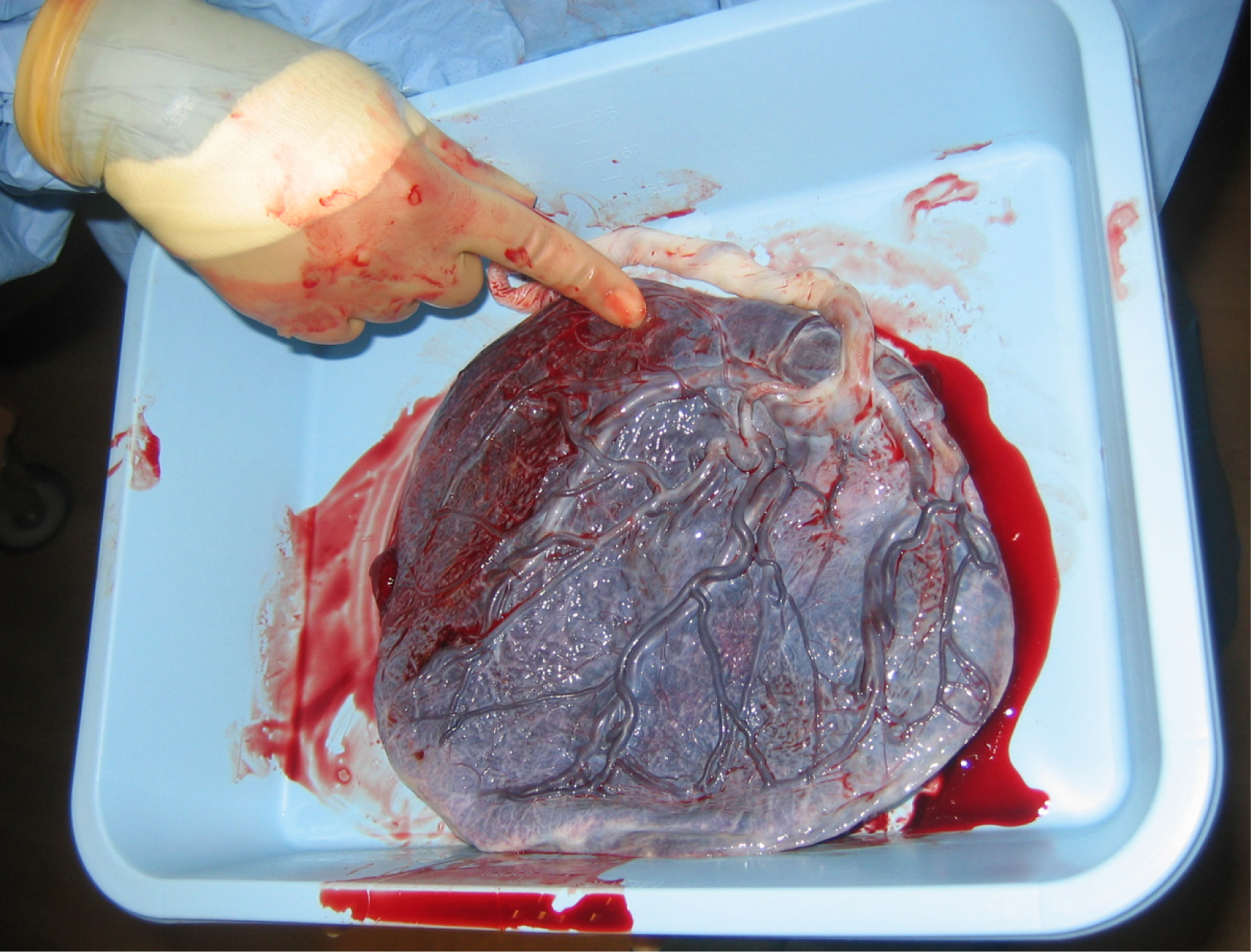

Development of the Placenta

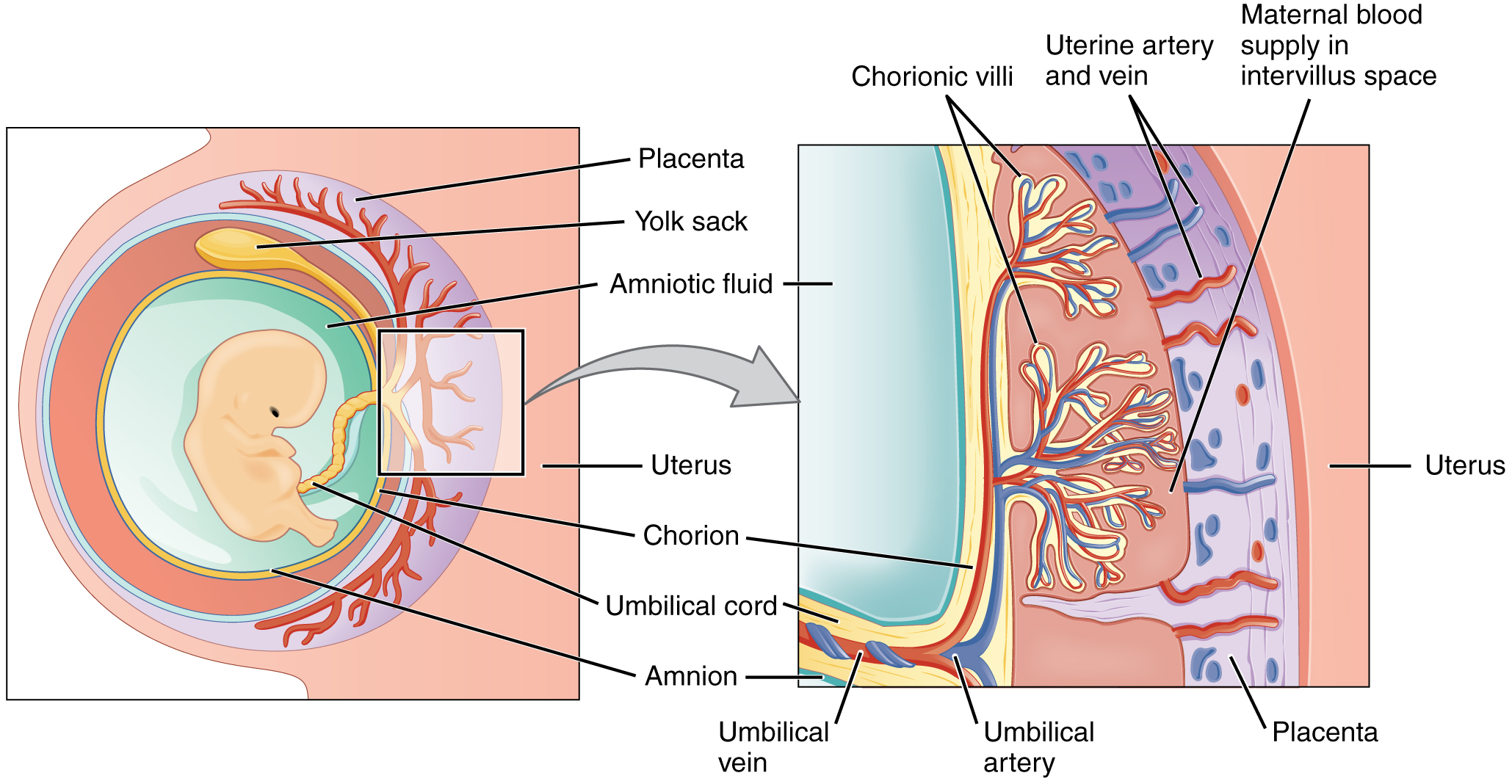

During the first several weeks of development, the cells of the endometrium—referred to as decidual cells—nourish the nascent embryo. During prenatal weeks 4 to 12, the developing placenta gradually takes over the role of feeding the embryo, and the decidual cells are no longer needed. The mature placenta is composed of tissues derived from the embryo, as well as maternal tissues of the endometrium. The placenta connects to the conceptus via the umbilical cord, which carries deoxygenated blood and wastes from the fetus through two umbilical arteries; nutrients and oxygen are carried from the mother to the fetus through the single umbilical vein. The umbilical cord is surrounded by the amnion, and the spaces within the cord around the blood vessels are filled with Wharton’s jelly, a mucous connective tissue.

The maternal portion of the placenta develops from the deepest layer of the endometrium, the decidua basalis. To form the embryonic portion of the placenta, the syncytiotrophoblast and the underlying cells of the trophoblast (cytotrophoblast cells) begin to proliferate along with a layer of extraembryonic mesoderm cells. These form the chorionic membrane, which envelops the entire conceptus as the chorion. The chorionic membrane forms finger-like structures called chorionic villi that burrow into the endometrium like tree roots, making up the fetal portion of the placenta. The cytotrophoblast cells perforate the chorionic villi, burrow farther into the endometrium, and remodel maternal blood vessels to augment maternal blood flow surrounding the villi. Meanwhile, fetal mesenchymal cells derived from the mesoderm fill the villi and differentiate into blood vessels, including the three umbilical blood vessels that connect the embryo to the developing placenta (Figure 19.2.8).

The placenta develops throughout the embryonic period and during the first several weeks of the fetal period; placentation is complete by weeks 14 to 16. As a fully developed organ, the placenta provides nutrition and excretion, respiration, and endocrine function (Table 19.2.1 and Figure 19.2.9). It receives blood from the fetus through the umbilical arteries. Capillaries in the chorionic villi filter fetal wastes out of the blood and return clean, oxygenated blood to the fetus through the umbilical vein. Nutrients and oxygen are transferred from maternal blood surrounding the villi through the capillaries and into the fetal bloodstream. Some substances move across the placenta by simple diffusion. Oxygen, carbon dioxide, and any other lipid-soluble substances take this route. Other substances move across by facilitated diffusion. This includes water-soluble glucose. The fetus has a high demand for amino acids and iron, and those substances are moved across the placenta by active transport.

Maternal and fetal blood does not commingle because blood cells cannot move across the placenta. This separation prevents the mother’s cytotoxic T cells from reaching and subsequently destroying the fetus, which bears “non-self” antigens. Further, it ensures the fetal red blood cells do not enter the mother’s circulation and trigger antibody development (if they carry “non-self” antigens)—at least until the final stages of pregnancy or birth. This is the reason that, even in the absence of preventive treatment, an Rh− mother doesn’t develop antibodies that could cause hemolytic disease in her first Rh+ fetus.

Although blood cells are not exchanged, the chorionic villi provide ample surface area for the two-way exchange of substances between maternal and fetal blood. The rate of exchange increases throughout gestation as the villi become thinner and increasingly branched. The placenta is permeable to lipid-soluble fetotoxic substances: alcohol, nicotine, barbiturates, antibiotics, certain pathogens, and many other substances that can be dangerous or fatal to the developing embryo or fetus. For these reasons, pregnant women should avoid fetotoxic substances. Alcohol consumption by pregnant women, for example, can result in a range of abnormalities referred to as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). These include organ and facial malformations, as well as cognitive and behavioral disorders.

| Nutrition and Digestion | Respiration | Endocrine Function |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Organogenesis

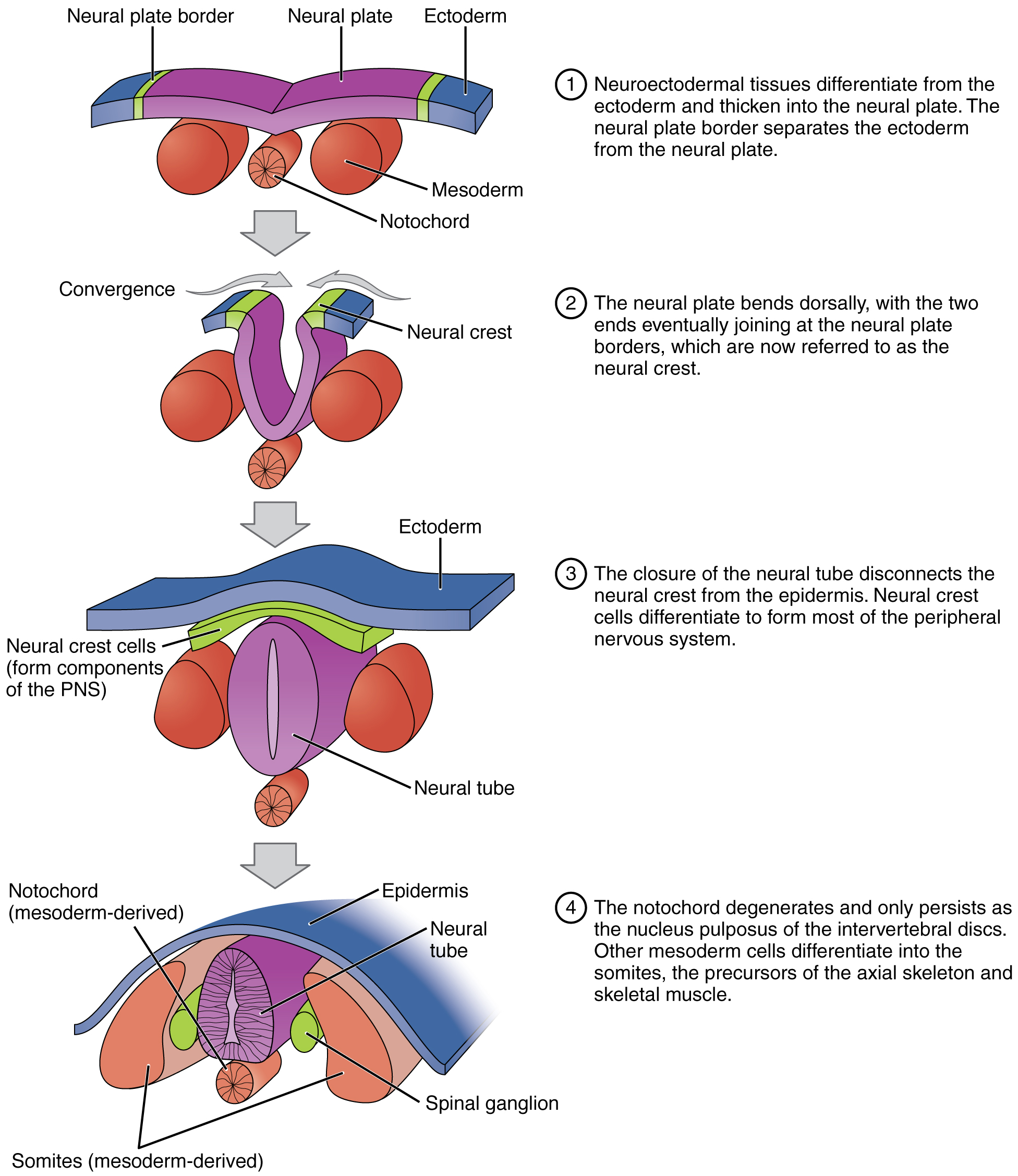

Following gastrulation, rudiments of the central nervous system develop from the ectoderm in the process of neurulation (Figure 19.2.10). Specialized neuroectodermal tissues along the length of the embryo thicken into the neural plate. During the fourth week, tissues on either side of the plate fold upward into a neural fold. The two folds converge to form the neural tube. The tube lies atop a rod-shaped, mesoderm-derived notochord, which eventually becomes the nucleus pulposus of intervertebral discs. Block-like structures called somites form on either side of the tube, eventually differentiating into the axial skeleton, skeletal muscle, and dermis. During the fourth and fifth weeks, the anterior neural tube dilates and subdivides to form vesicles that will become the brain structures.

Folate, one of the B vitamins, is important to the healthy development of the neural tube. A deficiency of maternal folate in the first weeks of pregnancy can result in neural tube defects, including spina bifida—a birth defect in which spinal tissue protrudes through the newborn’s vertebral column, which has failed to completely close. A more severe neural tube defect is anencephaly, a partial or complete absence of brain tissue.

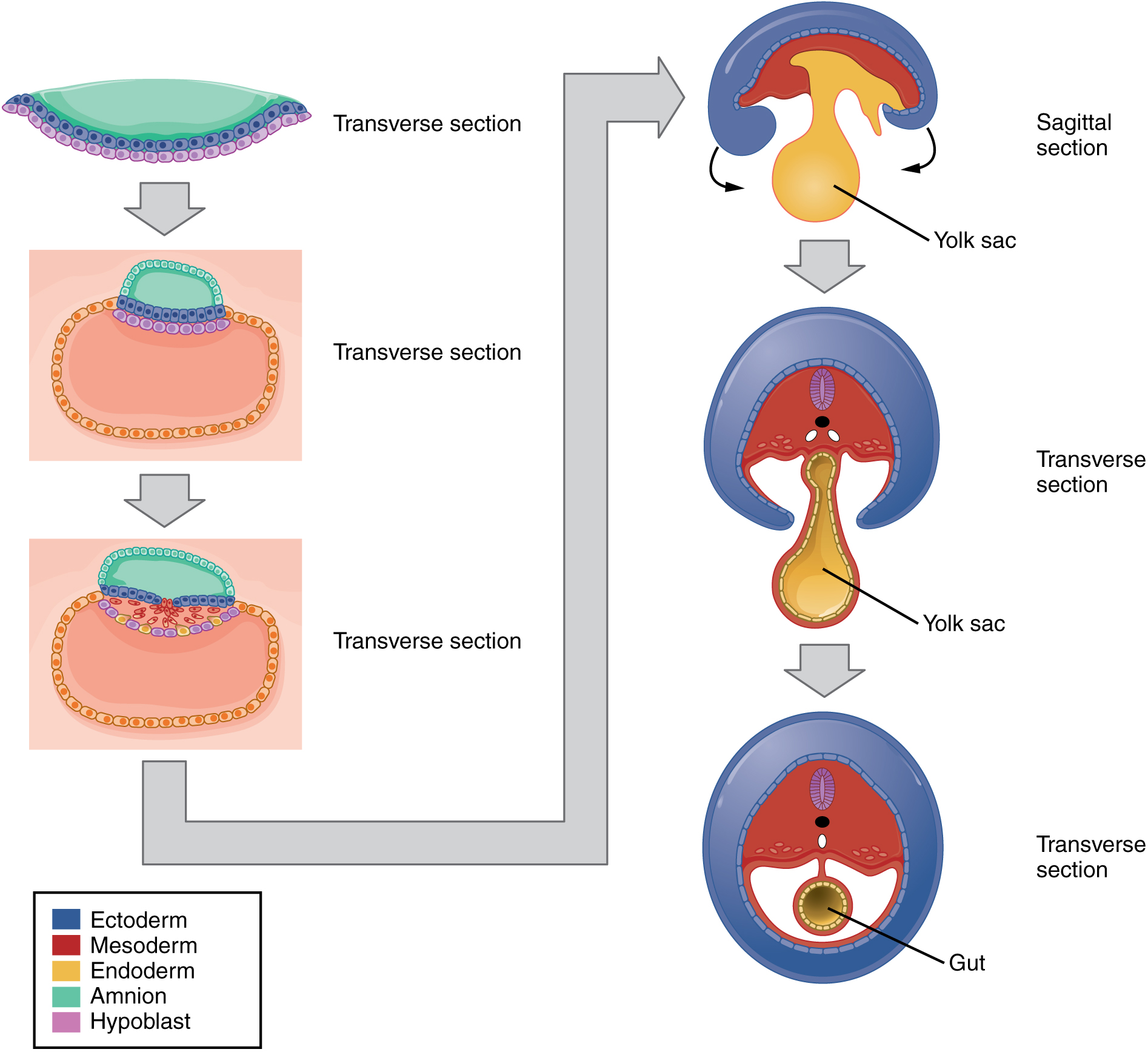

The embryo, which begins as a flat sheet of cells, begins to acquire a cylindrical shape through the process of embryonic folding (Figure 19.2.11). The embryo folds laterally and again at either end, forming a C-shape with distinct head and tail ends. The embryo envelops a portion of the yolk sac, which protrudes with the umbilical cord from what will become the abdomen. The folding essentially creates a tube, called the primitive gut, that is lined by the endoderm. The amniotic sac, which was sitting on top of the flat embryo, envelops the embryo as it folds.

Within the first 8 weeks of gestation, a developing embryo establishes the rudimentary structures of all of its organs and tissues from the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. This process is called organogenesis.

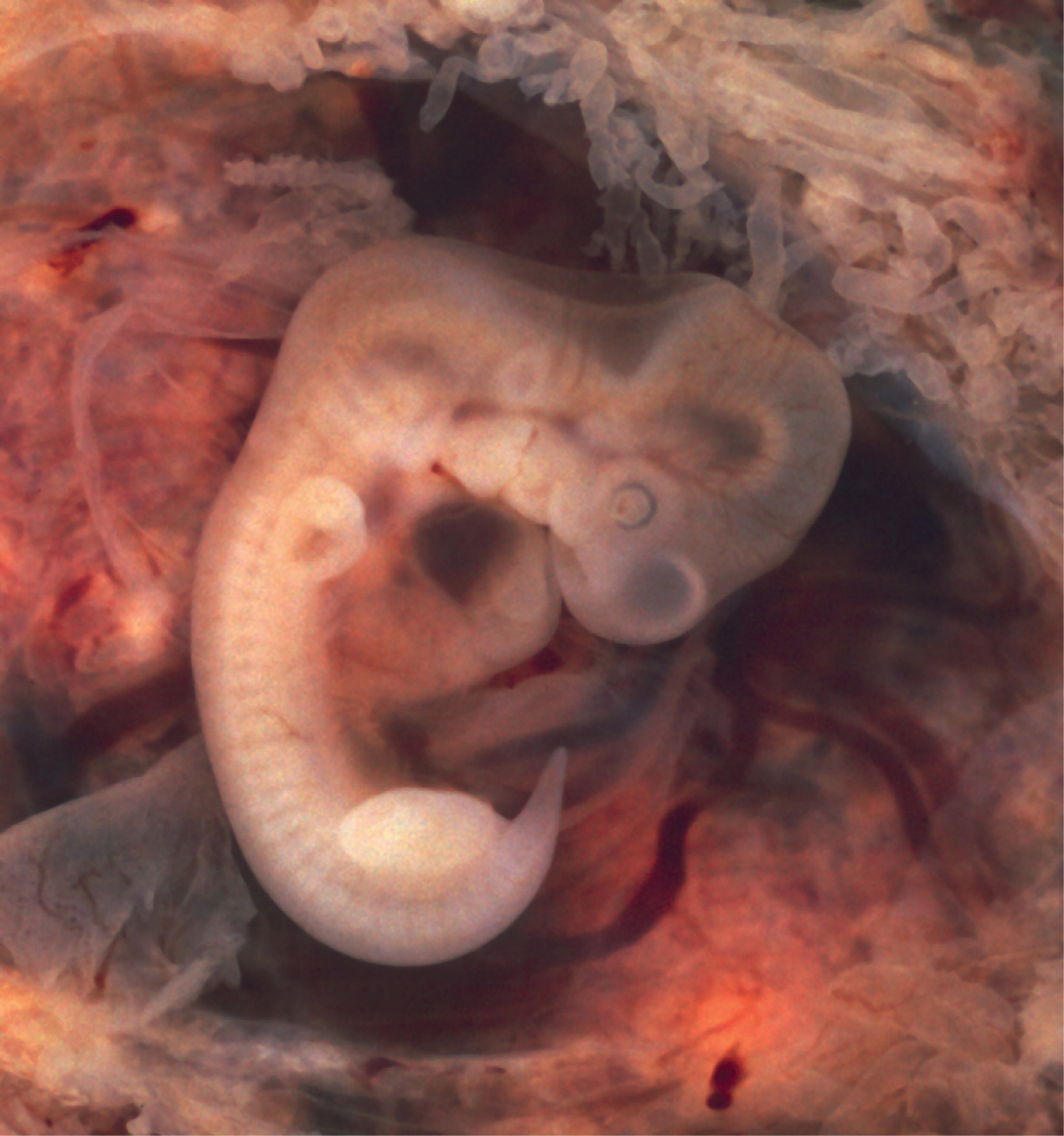

Like the central nervous system, the heart also begins its development in the embryo as a tube-like structure, connected via capillaries to the chorionic villi. Cells of the primitive tube-shaped heart are capable of electrical conduction and contraction. The heart begins beating in the beginning of the fourth week, although it does not actually pump embryonic blood until a week later, when the oversized liver has begun producing red blood cells. (This is a temporary responsibility of the embryonic liver that the bone marrow will assume during fetal development.) During weeks 4 to 5, the eye pits form, limb buds become apparent, and the rudiments of the pulmonary system are formed.

During the sixth week, uncontrolled fetal limb movements begin to occur. The gastrointestinal system develops too rapidly for the embryonic abdomen to accommodate it, and the intestines temporarily loop into the umbilical cord. Paddle-shaped hands and feet develop fingers and toes by the process of apoptosis (programmed cell death), which causes the tissues between the fingers to disintegrate. By week 7, the facial structure is more complex and includes nostrils, outer ears, and lenses (Figure 19.2.12). By week 8, the head is nearly as large as the rest of the embryo’s body, and all major brain structures are in place. The external genitalia are apparent, but at this point, male and female embryos are indistinguishable. Bone begins to replace cartilage in the embryonic skeleton through the process of ossification. By the end of the embryonic period, the embryo is approximately 3 centimeters (1.2 inches) from crown to rump and weighs approximately 8 grams (0.25 ounce).

Section Review

As the zygote travels toward the uterus, it undergoes numerous cleavages in which the number of cells doubles (blastomeres). Upon reaching the uterus, the conceptus has become a tightly packed sphere of cells called the morula, which then forms into a blastocyst consisting of an inner cell mass within a fluid-filled cavity surrounded by trophoblasts. The blastocyst implants in the uterine wall, the trophoblasts fuse to form a syncytiotrophoblast, and the conceptus is enveloped by the endometrium. Four embryonic membranes form to support the growing embryo: the amnion, the yolk sac, the allantois, and the chorion. The chorionic villi of the chorion extend into the endometrium to form the fetal portion of the placenta. The placenta supplies the growing embryo with oxygen and nutrients; it also removes carbon dioxide and other metabolic wastes.

Following implantation, embryonic cells undergo gastrulation, in which they differentiate and separate into an embryonic disc and establish three primary germ layers (the endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm). Through the process of embryonic folding, the fetus begins to take shape. Neurulation starts the process of the development of structures of the central nervous system and organogenesis establishes the basic plan for all organ systems.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

Glossary

- allantois

- finger-like outpocketing of yolk sac forms the primitive excretory duct of the embryo; precursor to the urinary bladder

- amnion

- transparent membranous sac that encloses the developing fetus and fills with amniotic fluid

- amniotic cavity

- cavity that opens up between the inner cell mass and the trophoblast; develops into amnion

- blastocoel

- fluid-filled cavity of the blastocyst

- blastocyst

- term for the conceptus at the developmental stage that consists of about 100 cells shaped into an inner cell mass that is fated to become the embryo and an outer trophoblast that is fated to become the associated fetal membranes and placenta

- blastomere

- daughter cell of a cleavage

- chorion

- membrane that develops from the syncytiotrophoblast, cytotrophoblast, and mesoderm; surrounds the embryo and forms the fetal portion of the placenta through the chorionic villi

- chorionic membrane

- precursor to the chorion; forms from extra-embryonic mesoderm cells

- chorionic villi

- projections of the chorionic membrane that burrow into the endometrium and develop into the placenta

- cleavage

- form of mitotic cell division in which the cell divides but the total volume remains unchanged; this process serves to produce smaller and smaller cells

- conceptus

- pre-implantation stage of a fertilized egg and its associated membranes

- ectoderm

- primary germ layer that develops into the central and peripheral nervous systems, sensory organs, epidermis, hair, and nails

- ectopic pregnancy

- implantation of an embryo outside of the uterus

- embryo

- developing human during weeks 3 to 8

- embryonic folding

- process by which an embryo develops from a flat disc of cells to a three-dimensional shape resembling a cylinder

- endoderm

- primary germ layer that goes on to form the gastrointestinal tract, liver, pancreas, and lungs

- epiblast

- upper layer of cells of the embryonic disc that forms from the inner cell mass; gives rise to all three germ layers

- fetus

- developing human during the time from the end of the embryonic period (week 9) to birth

- gastrulation

- process of cell migration and differentiation into three primary germ layers following cleavage and implantation

- gestation

- in human development, the period required for embryonic and fetal development in utero; pregnancy

- human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG)

- hormone that directs the corpus luteum to survive, enlarge, and continue producing progesterone and estrogen to suppress menses and secure an environment suitable for the developing embryo

- hypoblast

- lower layer of cells of the embryonic disc that extend into the blastocoel to form the yolk sac

- implantation

- process by which a blastocyst embeds itself in the uterine endometrium

- inner cell mass

- cluster of cells within the blastocyst that is fated to become the embryo

- mesoderm

- primary germ layer that becomes the skeleton, muscles, connective tissue, heart, blood vessels, and kidneys

- morula

- tightly packed sphere of blastomeres that has reached the uterus but has not yet implanted itself

- neural plate

- thickened layer of neuroepithelium that runs longitudinally along the dorsal surface of an embryo and gives rise to nervous system tissue

- neural fold

- elevated edge of the neural groove

- neural tube

- precursor to structures of the central nervous system, formed by the invagination and separation of neuroepithelium

- neurulation

- embryonic process that establishes the central nervous system

- notochord

- rod-shaped, mesoderm-derived structure that provides support for growing fetus

- organogenesis

- development of the rudimentary structures of all of an embryo’s organs from the germ layers

- placenta

- organ that forms during pregnancy to nourish the developing fetus; also regulates waste and gas exchange between mother and fetus

- placenta previa

- low placement of fetus within uterus causes placenta to partially or completely cover the opening of the cervix as it grows

- placentation

- formation of the placenta; complete by weeks 14 to 16 of pregnancy

- primitive streak

- indentation along the dorsal surface of the epiblast through which cells migrate to form the endoderm and mesoderm during gastrulation

- somite

- one of the paired, repeating blocks of tissue located on either side of the notochord in the early embryo

- syncytiotrophoblast

- superficial cells of the trophoblast that fuse to form a multinucleated body that digests endometrial cells to firmly secure the blastocyst to the uterine wall

- trophoblast

- fluid-filled shell of squamous cells destined to become the chorionic villi, placenta, and associated fetal membranes

- umbilical cord

- connection between the developing conceptus and the placenta; carries deoxygenated blood and wastes from the fetus and returns nutrients and oxygen from the mother

- yolk sac

- membrane associated with primitive circulation to the developing embryo; source of the first blood cells and germ cells and contributes to the umbilical cord structure

Glossary Flashcards

This work, Human Physiology, is adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, licensed under CC BY. This edition, with revised content and artwork, is licensed under CC BY-SA except where otherwise noted.

Images from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax are licensed under CC BY except where otherwise noted.

Access the original for free at OpenStax.

Image Descriptions

Figure 19.2.1. This diagram illustrates the progressive stages of early embryonic development, divided into two phases based on location. The top row (red background) shows stages occurring in the uterine tube: the two-cell stage displays two large cells with visible nuclei surrounded by the zona pellucida; the four-cell stage shows four cells tightly packed within the zona pellucida with one darker shaded cell; and the eight-cell stage depicts eight cells arranged in a compact cluster within the zona pellucida. The bottom row (blue background) presents stages occurring in the uterus: the morula (16 cells) appears as a solid ball of cells with a textured surface still enclosed by the zona pellucida; the blastocyst (70-100 cells) shows a hollow sphere with a fluid-filled cavity, where cells have differentiated into two distinct populations; and a detailed cross-section of the blastocyst identifies the outer layer of cells as the trophoblast (which will form placental structures) and a cluster of cells positioned to one side as the inner cell mass (which will develop into the embryo proper), with the central fluid-filled space labeled as the blastocoel. Each stage is depicted as a black and white illustration showing increasing cellular organization and differentiation as the embryo progresses from the initial cleavage divisions to the formation of the blastocyst structure ready for implantation. [Return to Figure 19.2.1]

Figure 19.2.2. This diagram illustrates the developmental stages from fertilization through implantation. Stage 1 shows an unfertilized oocyte (egg cell) with visible nucleus and cytoplasm surrounded by the zona pellucida. Stage 2 depicts the fertilized oocyte after sperm penetration, with sperm cells surrounding it. Stage 3 shows the two-cell stage following the first cleavage division, with two cells visible within the zona pellucida. Stage 4 presents the four-cell stage, showing four cells arranged within the zona pellucida. Stage 5 displays the eight-cell stage as a compact cluster of eight cells. Stage 5 (second panel) illustrates the morula containing 16 cells as a solid ball. Stage 6 shows the blastocyst (70-100 cells) with two distinct structures: the outer trophoblast layer (cells that will form the placenta) and the inner cell mass (cluster of cells that will develop into the embryo), surrounding a fluid-filled cavity called the blastocoel. The center of the image shows a cross-section of the uterus with gray arrows indicating the path of the developing embryo through the uterine tube and into the uterus. The uterine cavity contains the developing embryo, with the endometrium (uterine lining) shown in layers. Stage 7 describes embryo hatching, where the blastocyst sheds its zona pellucida. Stage 8 shows the blastocyst rotating and implanting into the endometrium of the uterus, with the trophoblast beginning to invade the uterine wall to establish pregnancy. [Return to Figure 19.2.2]

Figure 19.2.3. This diagram illustrates the process of blastocyst implantation in three sequential stages. In stage 1, the blastocyst (shown as a blue sphere with an outer ring of cells called trophoblast and inner cell mass) approaches the uterine mucosa cells (pink layer) lining the uterine cavity. The endometrium (tan/beige layered tissue) lies beneath the mucosa. The blastocyst begins digesting the uterine mucosa as it initially implants into the endometrium. Stage 2 shows the blastocyst now partially embedded, with the endometrium growing over and beginning to surround the embryo, fully securing it to the uterine lining. The trophoblast cells have invaded deeper into the endometrial tissue. Stage 3 presents a cross-sectional view of the uterus showing the implanted embryo (depicted at 7-8 weeks after conception) continuing to develop within the endometrium. An inset box displays two simplified uterus diagrams in anterior and lateral views, with the posterior uterine wall highlighted in purple, indicating the most common site of implantation. The uterine cavity is visible above the embedded embryo, and the muscular uterine wall surrounds the developing pregnancy. Gray arrows between stages indicate the progression of implantation from initial contact through complete embedding in the endometrial lining. [Return to Figure 19.2.3]

Figure 19.2.4. This diagram compares two placental positions during pregnancy through cross-sectional views of the uterus. The left panel shows normal placental location, where a fetus in the head-down position is surrounded by amniotic fluid (pink), with the placenta (dark red disc-shaped organ with striations) attached to the upper portion of the uterine wall. The cervix at the bottom of the uterus is not obstructed, allowing for normal vaginal delivery. The right panel illustrates placenta previa, a complication where the placenta is abnormally positioned in the lower uterine segment. In this condition, the placenta covers the internal os (opening of the cervix), preventing proper birth as the baby cannot pass through the birth canal. Both diagrams show the fetus as a white outline, the amniotic cavity in light pink, the uterine wall in darker pink layers, and the placenta as a red striated structure. The key anatomical difference is the placental attachment site: high on the uterine wall in the normal presentation versus low and covering the cervical opening in placenta previa. [Return to Figure 19.2.4]

Figure 19.2.5. This diagram illustrates early embryonic development following implantation in the uterine endometrium. At the center, the embryonic disc consists of two layers: the epiblast (light blue cells) and hypoblast (purple cells), which will develop into the embryo proper. Surrounding the embryonic disc are two fluid-filled cavities separated by the disc: the amniotic cavity (green space) above, bordered by the amnion (light blue cell layer), and the blastocyst cavity below (orange space with small vesicles), which will develop into the yolk sac. The outer trophoblast layer has differentiated into two distinct regions: the cytotrophoblast (inner layer of individual orange cells with visible nuclei) and the syncytiotrophoblast (outer multinucleated layer appearing as fused orange cells), which together facilitate implantation and placental development. The entire structure is embedded within the endometrium (pink vascularized tissue at top and bottom), which shows blood vessels (red lines) providing maternal blood supply. This cross-sectional view demonstrates how the developing embryo is completely surrounded by maternal tissue while maintaining distinct embryonic and extraembryonic compartments that will support further development. [Return to Figure 19.2.5]

Figure 19.2.6. This two-panel diagram illustrates the process of gastrulation during early embryonic development. The top panel shows the bilaminar embryonic disc stage, with the embryo consisting of two primary layers: the epiblast (blue cells surrounding the amniotic cavity) and the hypoblast (purple cells below). The structure is embedded in the endometrium (pink tissue) with the reestablished uterine mucosa forming the outer boundary. The trophoblast (orange outer cells) surrounds the entire embryo, and the amniotic cavity (green space) is visible in the center. The bottom panel depicts gastrulation, where the embryo transforms into a trilaminar structure with three germ layers. A primitive streak forms (shown in the magnified inset with various colored cells), and cells differentiate and migrate from this region. The three germ layers are now labeled: ectoderm (pink outer layer derived from epiblast), mesoderm (purple-pink middle layer formed by migrating cells), and endoderm (yellow inner layer formed by displaced hypoblast cells). The magnified inset on the right shows the cellular detail of the primitive streak, where cells are actively migrating to form the mesodermal layer while displacing most hypoblast cells to create the endodermal layer. A small diagram in the upper right shows the level of cross-section as a horizontal line through an oval representing the embryonic disc. The text explains that cells differentiate at the primitive streak and migrate to form the middle mesodermal layer, displace most hypoblast cells to form the endodermal layer, and the ectoderm forms from the remaining epiblast. [Return to Figure 19.2.6]

Figure 19.2.7. This diagram illustrates the embryo at approximately four weeks of development, showing the three primary germ layers and associated extraembryonic structures. The embryo appears as a curved, crescent-shaped structure embedded in the endometrium (pink uterine tissue). At the center, a curled embryo (shown in purple and red) is surrounded by the amniotic cavity containing amniotic fluid (light blue space). The amnion (thin membrane) lines the amniotic cavity. Below the embryo, the yolk sac (shown in yellow) is lined with endoderm. The entire structure is enveloped by the chorion, a thick, irregular orange-tan membrane derived from the blastocyst cavity membrane, which extends into the maternal blood pool (dark red space at top) where maternal-fetal exchange occurs. The allantois (small tubular structure) extends from the embryo toward the chorion. Three text boxes at the bottom explain the developmental fates of each germ layer. The endoderm layer (inner yellow layer) becomes the digestive system, liver, pancreas, and inner layers of lungs. The mesoderm layer (middle blue-purple layer) develops into the circulatory system, epithelial layers of lungs, skeletal system, and muscular system. The ectoderm layer (outer layer adjacent to amniotic cavity) forms hair, nails, skin, and the nervous system. This organization demonstrates how the three germ layers established during gastrulation will differentiate into all the major organ systems and tissues of the body. [Return to Figure 19.2.7]

Figure 19.2.8. This diagram illustrates the relationship between a developing fetus and the maternal circulation system through two connected views. The left panel shows a cross-sectional view of a fetus within the uterus, surrounded by amniotic fluid (light blue) and enclosed by the amnion membrane (thin yellow line). The fetus is positioned within the uterine cavity, with the placenta (pink disc-shaped organ) attached to the uterine wall. The yolk sac (yellow sac-like structure) is visible near the umbilical cord attachment site. The chorion (outer membrane layer) surrounds the entire gestational sac. The umbilical cord connects the fetus to the placenta, containing blood vessels for nutrient and waste exchange. The right panel provides a magnified view of the placental interface, showing the detailed structure where maternal and fetal circulations come into close contact without directly mixing. Chorionic villi (finger-like projections in pink) extend from the fetal side into the intervillus space (shown in light pink/purple), which is filled with maternal blood from the maternal blood supply in the intervillus space. The uterine artery and vein (red and blue vessels) deliver and remove maternal blood from this space. Within each villus, fetal blood vessels (umbilical artery in blue and umbilical vein in red) carry deoxygenated blood from the fetus and return oxygenated blood, respectively. The thin barrier between maternal blood in the intervillus space and fetal blood in the villous capillaries allows for efficient exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and waste products while keeping the two blood supplies separate. The uterine wall is shown in light blue on the left side of the magnified view. [Return to Figure 19.2.8]

Figure 19.2.10. This diagram illustrates the four-stage process of neural tube formation and neural crest development during embryogenesis. Stage 1 shows a cross-sectional view where the neural plate (purple flat sheet) lies centrally on the ectoderm (blue outer layer), with neural plate borders (yellow-green regions) separating it from surrounding ectoderm. Below are three spherical structures representing mesoderm (large red spheres on sides) and the notochord (smaller orange sphere with radial pattern in center). Step 1 explains that neuroectodermal tissues differentiate from the ectoderm and thicken into the neural plate, with the neural plate border separating the ectoderm from the neural plate. Stage 2 depicts convergence, where the neural plate bends dorsally (upward) and the edges begin to elevate. The neural plate borders (now labeled as neural crest in yellow-green) move toward the midline as the plate folds. Step 2 notes that the neural plate bends dorsally with the two ends eventually joining at the neural plate borders, now called the neural crest. Stage 3 shows the completed neural tube (purple tubular structure) now enclosed beneath the ectoderm (blue surface layer). Neural crest cells (green layer) separate from the neural tube and position themselves between the ectoderm and mesoderm. Step 3 explains that closure of the neural tube disconnects the neural crest from the epidermis, and neural crest cells differentiate to form most of the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Stage 4 presents the final configuration with the epidermis (blue wavy surface) on top, the fully formed neural tube (purple with internal cavity and striations) in the center, and bilateral structures derived from mesoderm including somites (large red-orange masses) and spinal ganglia (small green spheres). The notochord (orange structure below) is labeled as mesoderm-derived. Step 4 states that the notochord degenerates and only persists as the nucleus pulposus of intervertebral discs, while other mesoderm cells differentiate into somites and the precursors of the axial skeleton and skeletal muscle. Gray arrows between stages indicate the progressive developmental sequence from flat neural plate to closed neural tube. [Return to Figure 19.2.10]

Figure 19.2.11. This diagram illustrates the process of embryonic folding, showing how a flat trilaminar embryonic disc transforms into a three-dimensional embryo. The left side displays three transverse (cross-sectional) views showing lateral folding, while the right side shows three corresponding views including one sagittal (lengthwise) section and two transverse sections. A color key indicates five tissue layers: ectoderm (dark blue outer layer), mesoderm (red middle layer), endoderm (yellow/tan inner layer), amnion (light green), and hypoblast (pink/purple). The top left shows the initial flat disc with distinct layers arranged horizontally. As development proceeds downward through the left column, the embryo curves and folds laterally, with edges lifting upward and inward. The top right sagittal view shows the embryo curved with the yolk sac (yellow-tan structure) positioned ventrally. The middle right transverse section demonstrates how the yolk sac connects to the developing gut tube, surrounded by the folding mesoderm and ectoderm layers. The bottom view on both sides shows the nearly complete cylindrical embryo, with the endoderm forming an enclosed gut tube (labeled “Gut”), the mesoderm surrounding it, and the ectoderm forming the outer body wall. The yolk sac remains connected to the gut via a narrowing stalk. Gray arrows between stages indicate the progression of folding. This transformation converts the flat embryonic disc into a tubular body plan with distinct internal cavities and external body wall, establishing the basic vertebrate body organization. [Return to Figure 19.2.11]

Report an Error

Did you find an error, typo, broken link, or other problem in the text? Please follow this link to the error reporting form to submit an error report to the authors.