Chapter 6. The Central Nervous System

6.3 Brain Structure

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Differentiate between white and gray matter

- Differentiate between (1) a nucleus and a ganglion and (2) a nerve and a tract

- Label gyrus and sulcus on a diagram

As we start learning about the central nervous system, a few terms and concepts will be used frequently. We will explore them in this section.

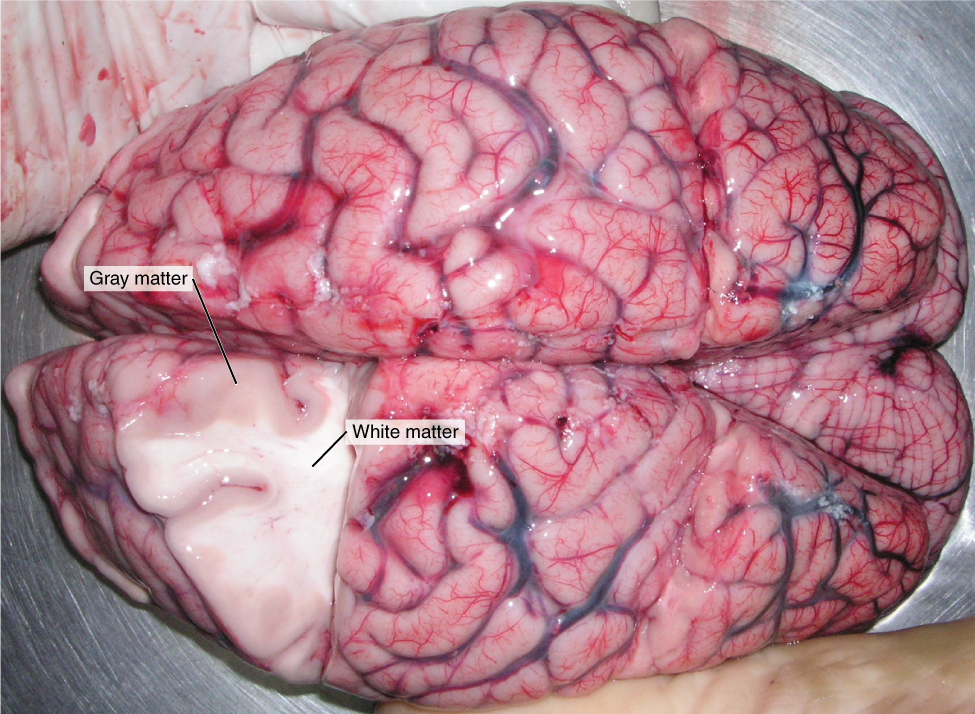

Gray and White Matter

Looking at nervous tissue, there are regions that predominantly contain cell bodies and regions that are largely composed of just axons. These two regions within nervous system structures are often referred to as gray matter (the regions with many cell bodies and dendrites) or white matter (the regions with many axons). Figure 6.3.1 demonstrates the appearance of these regions in the brain and spinal cord. The colors ascribed to these regions are what would be seen in “fresh,” or unstained, nervous tissue. Gray matter is not necessarily gray. It can be pinkish because of blood content, or even slightly tan, depending on how long the tissue has been preserved. But white matter is white because axons are insulated by a lipid-rich substance called myelin. Lipids can appear as white (“fatty”) material, much like the fat on a raw piece of chicken or beef. Actually, gray matter may have that color ascribed to it because next to the white matter, it is just darker—hence, gray.

Cell Bodies and Axons

Regardless of the appearance of stained or unstained tissue, the cell bodies of neurons or axons can be located in discrete anatomical structures that need to be named. Those names are specific to whether the structure is central or peripheral. A localized collection of neuron cell bodies in the central nervous system (CNS) is referred to as a nucleus. In the peripheral nervous system (PNS), a cluster of neuron cell bodies is referred to as a ganglion.

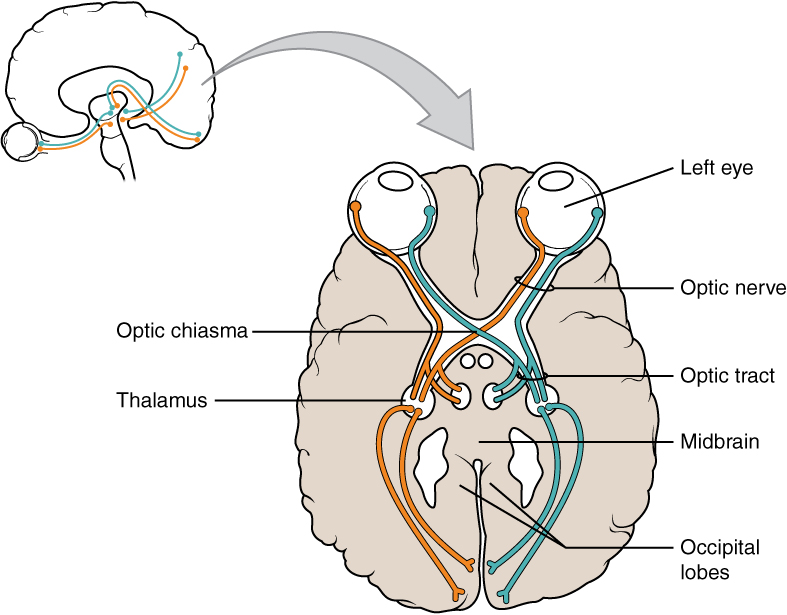

Terminology applied to bundles of axons also differs depending on location. A bundle of axons, or fibers, found in the CNS is called a tract, whereas the same thing in the PNS would be called a nerve. There is an important point to make about these terms, which is that they can both be used to refer to the same bundle of axons. The most obvious example of this is the axons that project from the retina into the brain. Those axons are called the optic nerve as they leave the eye, but when they are inside the cranium, they are referred to as the optic tract. There is a specific place where the name changes, which is the optic chiasm, but they are still the same axons (Figure 6.3.2). A similar situation outside of science can be described for some roads. Imagine a road called “Broad Street” in a town called “Anyville.” The road leaves Anyville and goes to the next town over, called “Hometown.” When the road crosses the line between the two towns and is in Hometown, its name changes to “Main Street.” That is the idea behind the naming of the retinal axons. In the PNS, they are called the optic nerve, and in the CNS, they are the optic tract. Table 6.1 helps to clarify which of these terms apply to the central or peripheral nervous systems.

| Category | CNS | PNS |

|---|---|---|

| Group of neuron cell bodies (i.e., gray matter) | Nucleus | Ganglion |

| Bundle of axons (i.e., white matter) | Tract | Nerve |

Gyrus and Sulcus

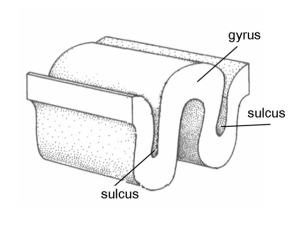

The surface human brain is not a smooth structure. It contains ridges and grooves. A gyrus (plural gyri) is the ridge of one of those wrinkles, and a sulcus (plural sulci) is the groove between two gyri. A fissure is a deeper sulcus. A good way to remember them is that sulcus is similar to the word sulking, which can mean being or feeling down.

Section Review

Considering the anatomical regions of the nervous system, there are specific names for the structures within each division. A localized collection of neuron cell bodies is referred to as a nucleus in the CNS and as a ganglion in the PNS. A bundle of axons is referred to as a tract in the CNS and as a nerve in the PNS. Whereas nuclei and ganglia are specifically in the central or peripheral divisions, axons can cross the boundary between the two. A single axon can be part of a nerve and a tract. The name for that specific structure depends on its location.

Nervous tissue can also be described as gray matter and white matter on the basis of its appearance in unstained tissue. These descriptions are more often used in the CNS. Gray matter is where nuclei are found, and white matter is where tracts are found. In the PNS, ganglia are basically gray matter and nerves are white matter.

Review Questions

Glossary

- ganglion

- localized collection of neuron cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system

- gray matter

- regions of the nervous system containing cell bodies of neurons with few or no myelinated axons; actually may be more pink or tan in color, but called gray in contrast to white matter

- gyrus

- ridge formed by convolutions on the surface of the cerebrum or cerebellum

- nerve

- cord-like bundle of axons located in the peripheral nervous system that transmits sensory input and response output to and from the central nervous system

- nucleus

- in the nervous system, a localized collection of neuron cell bodies that are functionally related; a “center” of neural function

- sulcus

- groove formed by convolutions in the surface of the cerebral cortex

- tract

- bundle of axons in the central nervous system having the same function and point of origin

- white matter

- regions of the nervous system containing mostly myelinated axons, making the tissue appear white because of the high lipid content of myelin

Glossary Flashcards

This work, Human Physiology, is adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, licensed under CC BY. This edition, with revised content and artwork, is licensed under CC BY-SA except where otherwise noted.

Images from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax are licensed under CC BY except where otherwise noted.

Access the original for free at OpenStax.

Image Descriptions

Figure 6.3.1. This photograph shows the dorsal (top) side of a human brain specimen resting in a stainless steel container. The brain displays its natural pink coloration with a network of red blood vessels visible across the folded surface of the cerebral cortex. The right side of the occipital lobe (back portion of the brain) has been shaved away to reveal the internal tissue architecture. In this exposed cross-section, two distinct tissue types are clearly visible and labeled: white matter, which appears pale cream-colored and branches through the center like tree limbs, and gray matter, which appears darker pink and forms branching, curved structures that create a buffer between the white matter core and the outer surface of the brain. The white matter consists of nerve fibers connecting different brain regions, while the gray matter contains nerve cell bodies. This dissection clearly demonstrates how gray matter forms the outer cortex and follows the contours of the brain’s folds, while white matter comprises the interior branching network [Return to Figure 6.3.1]

Figure 6.3.2 This illustration shows a superior (top-down) view of a cross-section of the brain with the anterior (front) side at the top, where both eyes are clearly visible. The diagram traces how visual information from each eye travels to the brain’s processing centers. Each eye contains two nerve tracts shown in different colors—orange representing one pathway and blue representing the other. In the left eye, the left nerve tract (orange) travels straight back to the left side of the thalamus and then enters the left occipital lobe at the back of the brain. However, the right nerve tract (blue) from the left eye crosses to the opposite side of the brain through the optic chiasma, an X-shaped structure where the optic nerves meet. This crossed pathway travels through the right side of the thalamus and enters the right occipital lobe. In the right eye, the pattern is reversed: the left nerve tract (orange) crosses over to the left side of the brain at the optic chiasma, traveling into the left thalamus and left occipital lobe, while the right nerve tract (blue) leads straight back to the right thalamus and right occipital lobe without crossing. This crossing pattern at the optic chiasma ensures that visual information from the left visual field of both eyes reaches the right side of the brain, and information from the right visual field reaches the left side of the brain. The midbrain is also labeled in the center of the diagram. A small inset in the upper left shows the same pathway in a side view for reference. [Return to Figure 6.3.2]

Figure 6.3.3 This three-dimensional diagram illustrates the basic topography of the brain’s surface, showing two adjacent sections of cerebral cortex. The image depicts the characteristic folded structure of the brain’s outer layer, with raised ridges called gyri (labeled on the top portion) and grooved indentations called sulci (labeled in two locations where the tissue dips inward). The gyri appear as rounded, elevated bumps of brain tissue, while the sulci are the valleys or furrows between them. This folding pattern dramatically increases the brain’s surface area, allowing more neurons to fit within the confined space of the skull. The diagram is rendered in a simple line-drawing style with stippled shading to show the three-dimensional contours. The tissue is shown as solid blocks to emphasize the physical structure, making it easy to understand how the brain’s surface creates these alternating peaks and valleys across its entire outer layer. [Return to Figure 6.3.3]

Report an Error

Did you find an error, typo, broken link, or other problem in the text? Please follow this link to the error reporting form to submit an error report to the authors.