Chapter 8. Muscle Tissue

8.4 Nervous System Control of Muscle Tension

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain concentric, isotonic, and eccentric contractions

- Define the following terms: muscle tension (force), twitch, muscle tone, and motor unit

- Describe how action potential frequency and the recruitment of different size motor units are used to progressively increase muscle tension

- Explain how changes in muscle length and sliding filament zone of overlap are associated with changes in muscle tension, as illustrated in a muscle length-tension graph

- Label the latent, contraction, and relaxation periods of a muscle twitch graph and describe the cellular and molecular events that occur in each period

- Define wave summation, tetanus, and treppe

- Interpret graphs of muscle tension versus stimulus frequency to explain the physiological basis of summation, unfused tetanus, and complete tetanus

Types of Muscle Contraction

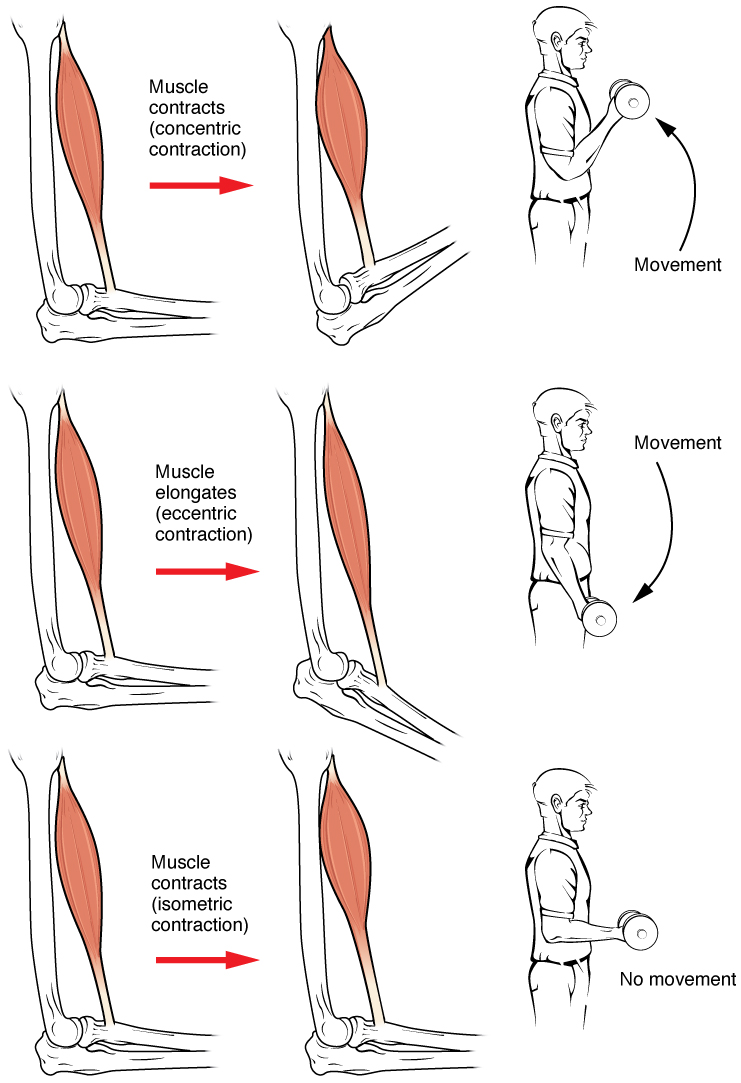

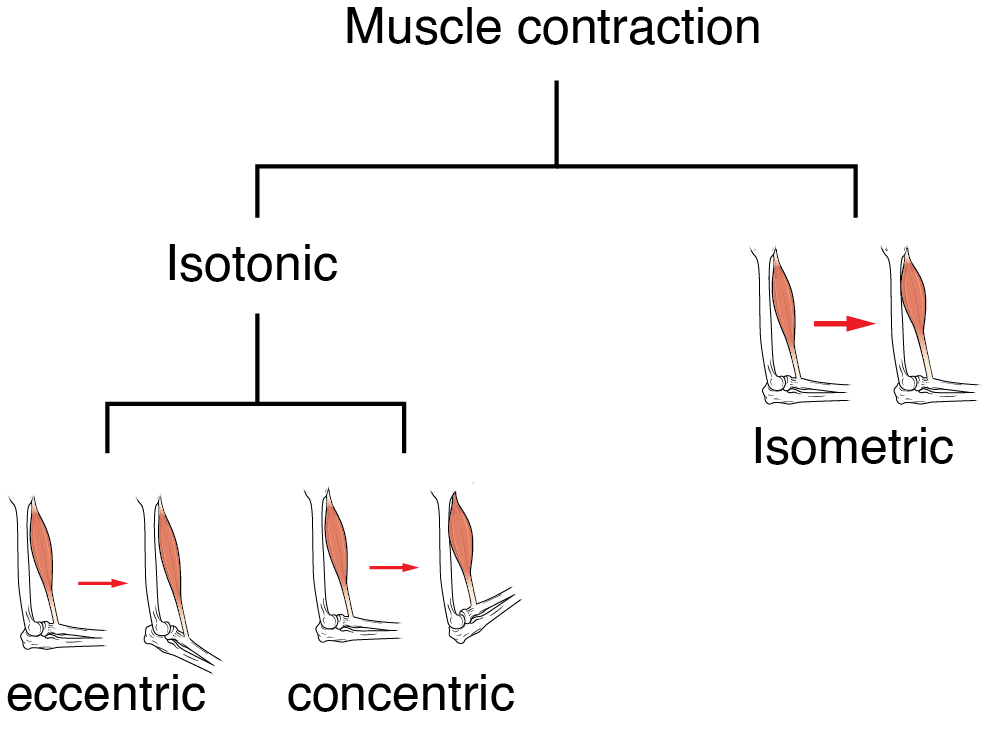

To move an object, referred to as a load, the muscle fibers of a skeletal muscle must shorten. The force generated by a contracting muscle is called muscle tension. Muscle tension can also be generated when the muscle is contracting against a load that does not move, resulting in two main types of skeletal muscle contractions: isotonic contractions and isometric contractions (Figure 8.4.1).

In isotonic contractions, where the tension in the muscle stays relatively constant, a load is moved as the length of the muscle changes. A concentric contraction involves the muscle producing tension and shortening to move a load. An example of this is the contraction of the biceps brachii muscle when a hand weight is brought upward toward the body. An eccentric contraction occurs when the muscle tension produced is less than the load and a muscle lengthens while under tension (Figure 8.4.2). This type of contraction is observed when the same hand weight is lowered in a slow and controlled manner by the biceps brachii. Both concentric and eccentric contractions involve force production by the muscle and crossbridge cycling with the myosin heads pulling toward the M-line. The only difference between the two is whether the muscle length is shortening or elongating during the contraction.

An isometric contraction occurs when a muscle produces tension without a change in muscle length (Figure 8.4.2). Isometric contractions involve sarcomere shortening and increasing muscle tension, but they do not move a load, as the force produced cannot overcome the resistance provided by the load. For example, if one attempts to lift a hand weight that is too heavy, there will be sarcomere activation and shortening to a point, along with ever-increasing muscle tension, but no change in the position of the hand weight. In everyday living, isometric contractions are active in maintaining posture and maintaining bone and joint stability.

Most actions of the body are the result of a combination of isotonic and isometric contractions working together to produce a wide range of outcomes. These muscle activities are under the control of the nervous system. A crucial aspect of nervous system control of skeletal muscles is the role of motor units.

Motor Units

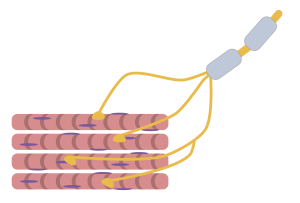

As previously discussed, the contraction of skeletal muscle fibers is triggered by signaling from a motor neuron. Each muscle fiber is innervated by only one motor neuron, but a single motor neuron can innervate multiple muscle fibers. A motor unit is defined a single motor neuron and all of the muscle fibers innervated by it (Figure 8.4.3).

The size of a motor unit dictates its function. A small motor unit, composed of a motor neuron and only a few muscle fibers, permits very fine motor control of a muscle. For example, the extraocular eye muscles have thousands of muscle fibers with every 5 to 10 fibers supplied by a single motor neuron; this allows for exquisite control of eye movements so that both eyes can quickly focus on an object. Small motor units are also involved in the many fine movements of the fingers and thumb of the hand for grasping, texting, and so on.

Large motor units have more muscle fibers per neuron than small motor units. Larger motor units are concerned with simple, or “gross,” movements, such as moving parts of the body against gravity. The large motor units of the thigh muscles or back muscles, where a single motor neuron will supply thousands of muscle fibers in a muscle, are representative of this type of activity.

Most muscles in the human body have a mixture of small and large motor units, which gives the nervous system a wide range of control over the muscle. The smaller motor units in a muscle have motor neurons that are more excitable. Initial activation of these smaller motor units results in a relatively small degree of tension generated in a muscle. As more strength is needed, larger motor units are enlisted to generate more tension. This process of bringing on additional motor units to produce more tension is known as recruitment. This process allows a muscle such as the biceps brachii to pick up a feather with minimal force generation versus picking up a heavy weight, which requires a much greater amount of force generation.

When necessary, the maximal number of motor units in a muscle can be recruited simultaneously, producing the maximum force of contraction for that muscle, but this cannot last for very long because of the energy requirements to sustain the contraction. To prevent complete muscle fatigue, motor units are generally not all simultaneously active, but instead some motor units rest while others are active, which allows for longer muscle contractions. The nervous system thus uses recruitment as a mechanism to efficiently utilize a skeletal muscle.

External Website

The Length-Tension Range of a Sarcomere

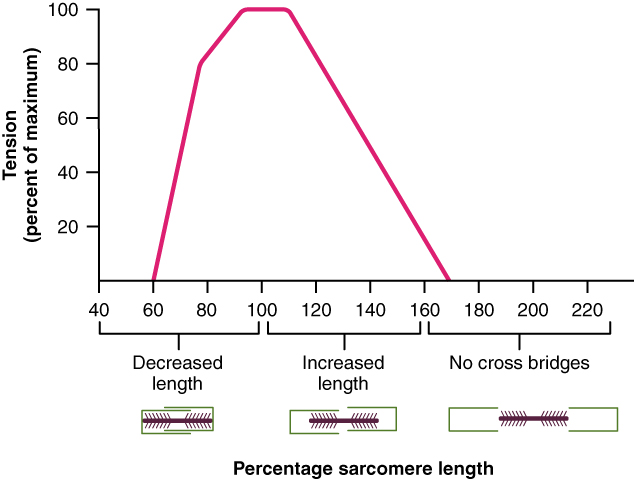

As discussed previously, when a skeletal muscle fiber contracts, myosin heads attach to actin to form cross-bridges followed by the thin filaments sliding over the thick filaments as the heads pull the actin, and this results in sarcomere shortening, creating the tension of the muscle contraction. The cross-bridges can only form where thin and thick filaments overlap; thus, the length of the sarcomere has a direct influence on the force generated when the sarcomere shortens. This is called the length-tension relationship.

The ideal length of a sarcomere to produce maximal tension occurs at 80% to 120% of its resting length, with 100% being the state where the medial edges of the thin filaments are just at the most-medial myosin heads of the thick filaments (Figure 8.4.4). This length maximizes the overlap of actin-binding sites and myosin heads.

If a sarcomere is stretched past the ideal length (beyond 120%), thick and thin filaments do not fully overlap, which results in less tension produced. If the muscle is stretched to the point where the thick and thin filaments do not overlap at all, no cross-bridges can be formed, and no tension can be generated. This amount of stretching does not usually occur as accessory proteins and connective tissue oppose extreme stretching.

If a sarcomere is shortened beyond 80%, the zone of overlap is reduced with the thin filaments jutting beyond the last of the myosin heads. Eventually, there is nowhere else for the thin filaments to go and the amount of tension is diminished.

The Frequency of Motor Neuron Stimulation

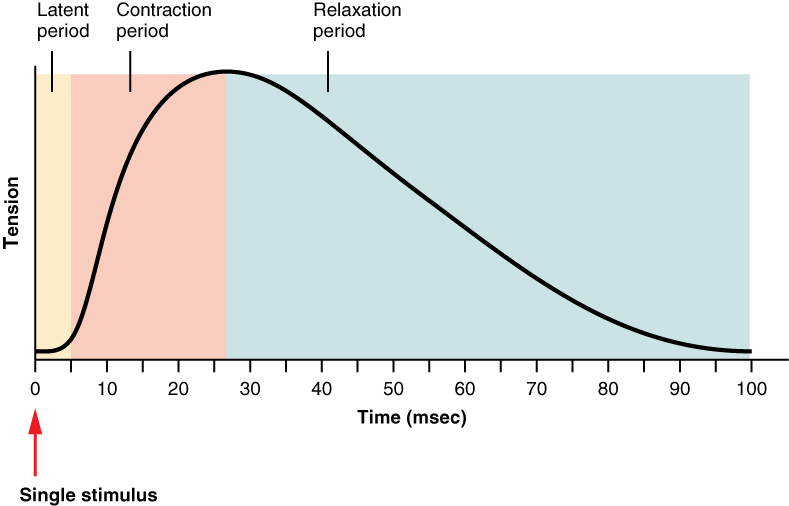

A single action potential from a motor neuron will produce a single contraction in the muscle fibers innervated by the motor neuron. This isolated contraction is called a twitch. A twitch can last anywhere from a few milliseconds to 100 milliseconds, depending on the muscle fiber type. The tension produced by a single twitch can be measured by a myogram, an instrument that measures the amount of tension produced over time (Figure 8.4.5).

Three phases are recognized for a muscle twitch. The first phase is the latent period, during which the action potential is being propagated along the sarcolemma and Ca++ ions are released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. This is the phase during which excitation and contraction are being coupled but contraction has yet to occur. The contraction phase occurs as the muscle generates increasing levels of tension; the Ca++ ions in the sarcoplasm have bound to troponin, tropomyosin has shifted away from actin-binding sites, cross-bridges have formed, and sarcomeres are actively shortening. The last phase is the relaxation phase, when tension decreases as Ca++ ions are pumped out of the sarcoplasm back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum, returning the muscle fibers to their resting state.

Although a person can experience a skeletal muscle “twitch,” a single twitch does not produce “useful” activity in a living body. Instead, a rapid series of action potentials sent to the muscle fibers is necessary for a muscle contraction that can produce work. By varying the rate at which a motor neuron fires action potentials, the amount of tension generated by the innervated muscle fibers can be modified; this is called a graded muscle response.

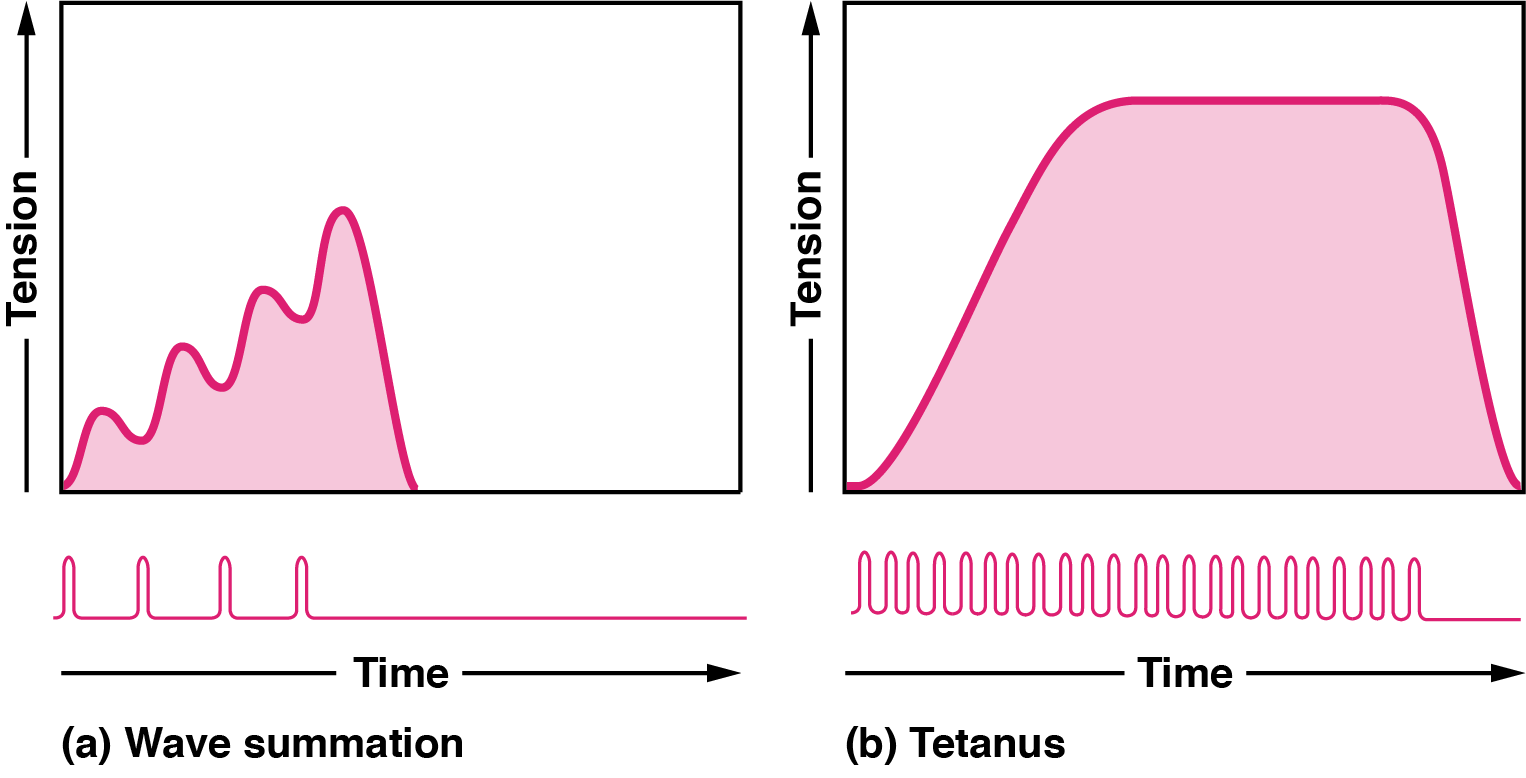

A graded muscle response works as follows: if the fibers are stimulated while a previous twitch is still occurring, the second twitch will be stronger. This response is called wave summation, because the excitation-contraction coupling effects of successive motor neuron signaling is summed, or added together (Figure 8.4.6a). At the molecular level, summation occurs because the second stimulus triggers the release of more Ca++ ions, which become available to activate more cross-bridging while the muscle is still contracting from the first stimulus. Summation results in greater contraction of the motor unit.

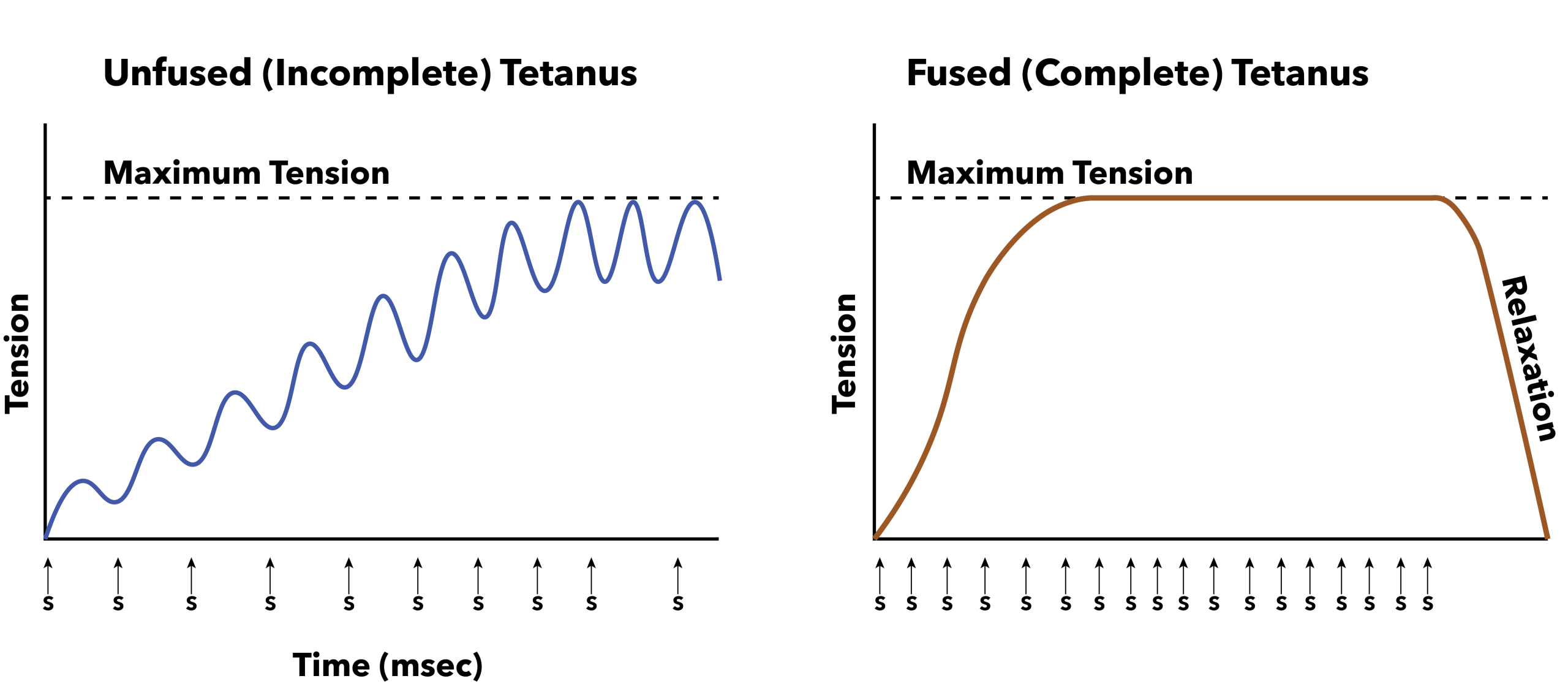

If the frequency of motor neuron signaling increases, summation and subsequent muscle tension in the motor unit continues to rise until it reaches a peak point. The tension at this point is about three to four times greater than the tension of a single twitch, a state referred to as incomplete tetanus. During incomplete tetanus, the muscle goes through quick cycles of contraction followed by a short relaxation phase (Figure 8.4.7). If the stimulus frequency is so high that the relaxation phase disappears completely, contractions become continuous in a process called complete tetanus (Figure 8.4.6b). During complete tetanus, the concentration of Ca++ ions in the sarcoplasm allows virtually all of the sarcomeres to form cross-bridges and shorten so that a contraction can continue uninterrupted (until the muscle fatigues and can no longer produce tension).

Treppe

When a skeletal muscle has been dormant for an extended period and then stimulated to contract, with all other things being equal, the initial contractions generate about half the force of later contractions. With successive stimulation (following relaxation), the muscle tension increases in a graded manner that to some looks like a set of stairs, eventually reaching a plateau at maximum tension. This type of tension increase is called treppe, a condition where muscle contractions become more efficient. It’s also known as the “staircase effect.” It is believed that treppe results from a higher concentration of Ca++ in the sarcoplasm resulting from the steady stream of signals from the motor neuron. It can only be maintained with adequate ATP.

The key difference between treppe and wave summation is that during treppe the muscle is allowed to relax before a subsequent stimulation, whereas in wave summation the muscle is stimulated multiple times in a short interval of time before the muscle has a chance to fully relax from the last stimuli.

External Website

Muscle Tone

Muscle tone is accomplished by a complex interaction between the nervous system and skeletal muscles that results in the activation of a few motor units at a time, most likely in a cyclical manner. In this manner, muscles never fatigue completely, as some motor units are in a state of recovery while others are actively generating tension.

Disorders of the Muscles: Hypotonia

The absence of the low-level contractions that lead to muscle tone is referred to as hypotonia, or atrophy, and can result from damage to parts of the central nervous system (CNS), such as the cerebellum, or from loss of innervations to a skeletal muscle, as in poliomyelitis. Hypotonic muscles have a flaccid appearance and display functional impairments, such as weak reflexes. Conversely, excessive muscle tone is referred to as hypertonia, accompanied by hyperreflexia (excessive reflex responses), which is often the result of damage to upper motor neurons in the CNS. Hypertonia can present with muscle rigidity (as seen in Parkinson’s disease) or spasticity, a phasic change in muscle tone, where a limb will “snap” back from passive stretching (as seen in some strokes).

Section Review

The force generated by a contracting muscle is called muscle tension. There are two main types of skeletal muscle contractions: isotonic and isometric. Isotonic contractions can be further distinguished as concentric (shortening) or eccentric (lengthening). Most actions of the body are the result of a combination of isotonic and isometric contractions.

A motor unit is formed by a motor neuron and all of the muscle fibers that are innervated by that same motor neuron. A small motor unit, composed of a motor neuron and only a few muscle fibers, permits very fine motor control of a muscle. Larger motor units, in which a single motor neuron may supply thousands of muscle fibers, are concerned with simple, or “gross,” movements, such as moving parts of the body against gravity. Increasing the number of motor neurons activated increases the amount of motor units activated in a muscle, which is called recruitment. Motor unit recruitment can be used to generate greater muscle tension.

The number of cross-bridges formed between actin and myosin determines the amount of tension produced by a muscle. The length of a sarcomere is optimal when its length maximizes the overlap of actin-binding sites and myosin heads. Muscles that are stretched or compressed too greatly do not produce maximal amounts of power.

A single contraction is called a twitch. A muscle twitch has a latent period, a contraction phase, and a relaxation phase. A graded muscle response allows variation in muscle tension. Summation occurs as successive stimuli are added together to produce a stronger muscle contraction. Tetanus is the fusion of contractions to produce a continuous contraction. Muscle tone is the constant low-level contractions that allow for posture and stability.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

Glossary

- concentric contraction

- muscle contraction that shortens the muscle to move a load

- contraction phase

- twitch contraction phase when tension increases

- eccentric contraction

- muscle contraction that lengthens the muscle as the tension is diminished

- graded muscle response

- modification of contraction strength

- hypertonia

- abnormally high muscle tone

- hypotonia

- abnormally low muscle tone caused by the absence of low-level contractions

- isometric contraction

- muscle contraction that occurs with no change in muscle length

- isotonic contraction

- muscle contraction that involves changes in muscle length

- latent period

- the time when a twitch does not produce contraction

- motor unit

- motor neuron and the group of muscle fibers it innervates

- muscle tension

- force generated by the contraction of the muscle; tension generated during isotonic contractions and isometric contractions

- muscle tone

- low levels of muscle contraction that occur when a muscle is not producing movement

- myogram

- instrument used to measure twitch tension

- recruitment

- increase in the number of motor units involved in contraction

- relaxation phase

- period after twitch contraction when tension decreases

- unfused (incomplete) tetanus

- a muscle is stimulated at such a rate that it does not fully relax before the next stimuli and reaches maximum tension

- fused (complete) tetanus

- a muscle is stimulated at such a rate that it does not relax at all before the next stimuli, reaching and staying at maximum tension

- treppe

- stepwise increase in contraction tension when a muscle is successively stimulated (with relaxation) after being dormant for a long period and its contractions become more efficient

- twitch

- single contraction produced by one action potential

- wave summation

- addition of successive neural stimuli to produce greater contraction

Glossary Flashcards

This work, Human Physiology, is adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, licensed under CC BY. This edition, with revised content and artwork, is licensed under CC BY-SA except where otherwise noted.

Images from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax are licensed under CC BY except where otherwise noted.

Access the original for free at OpenStax.

Image Descriptions

Figure 8.4.1. This diagram illustrates three distinct types of muscle contractions using the biceps muscle as an example, with each type shown in a row. The top row demonstrates concentric contraction, where the muscle shortens as it contracts. The left panel shows the arm extended with the biceps relaxed, and a red arrow points to the middle panel where the biceps muscle (shown in coral/pink color) bulges and shortens as the elbow joint flexes. The right panel depicts a person performing a bicep curl, lifting a dumbbell upward with an arrow indicating the upward movement. The middle row illustrates eccentric contraction, where the muscle lengthens while maintaining tension. The left panel shows the arm in a partially flexed position, and the red arrow points to the middle panel where the biceps elongates as the arm extends, though the muscle remains engaged. The right panel shows the person lowering the dumbbell in a controlled manner, with an arrow indicating the downward movement. The bottom row presents isometric contraction, where the muscle generates tension without changing length. The left panel shows the arm in a fixed position, and the red arrow points to the middle panel where the muscle remains contracted but neither shortens nor lengthens. The right panel depicts the person holding a dumbbell in a static position with no movement, demonstrating the muscle maintaining constant length while under load. [Return to Figure 8.4.1]

Figure 8.4.2. This organizational diagram presents a hierarchical classification of muscle contraction types. At the top, “Muscle contraction” serves as the main category, which branches into two primary divisions: “Isotonic” on the left and “Isometric” on the right. The isotonic branch further subdivides into two subcategories shown at the bottom: “eccentric” and “concentric.” Each contraction type is illustrated with anatomical drawings of the lower leg showing the calf muscle in coral/pink color. For eccentric contraction, the left image shows a shortened muscle, and a red arrow points to the right image showing the muscle lengthening as the ankle extends. For concentric contraction, the left image displays an extended muscle, and a red arrow points to the right image showing the muscle shortening as the ankle plantarflexes. For isometric contraction, positioned on the upper right, two side-by-side images connected by a red arrow show the muscle maintaining constant length and position despite being contracted, demonstrating no change in joint angle or muscle length. [Return to Figure 8.4.2]

Figure 8.4.3. This illustration depicts a motor unit, which consists of a single motor neuron and the muscle fibers it controls. The diagram shows a motor neuron with a gray myelin sheath that branches into multiple terminal endings colored in yellow-orange. These nerve terminals connect to four parallel muscle fibers, each illustrated as cylindrical structures in pink with darker striations indicating the characteristic banding pattern of skeletal muscle. The neuron branches extend from upper right, dividing to reach each muscle fiber at distinct points along their length, forming neuromuscular junctions where the nerve terminals interface with the muscle tissue. [Return to Figure 8.4.3]

Figure 8.4.4. This graph illustrates the length-tension relationship in skeletal muscle, plotting tension as a percentage of maximum on the vertical axis against percentage sarcomere length on the horizontal axis. The curve forms a characteristic plateau shape, rising steeply from approximately 60% sarcomere length to reach maximum tension (100%) between 80% and 110% of optimal length, then declining symmetrically back to zero tension at about 170% length. Below the graph, three sarcomere diagrams show the arrangement of thick and thin filaments at different lengths. The left diagram, labeled “Decreased length,” shows extensive overlap of filaments at shorter sarcomere lengths (60-80% range). The middle diagram, labeled “Increased length,” depicts optimal filament overlap at intermediate lengths (120-160% range) where maximum tension is generated. The right diagram, labeled “No cross bridges,” shows filaments pulled too far apart at extended lengths (180-220% range) where thick and thin filaments no longer overlap, preventing cross-bridge formation and force generation. The thick filaments are represented by purple/burgundy lines with cross-hatching in the center, while thin filaments extend from both ends in a lighter color. [Return to Figure 8.4.4]

Figure 8.4.5. This graph illustrates a single muscle twitch response to a stimulus over time, with tension plotted on the vertical axis and time in milliseconds on the horizontal axis from 0 to 100 msec. A red arrow at the bottom left marks the point of “Single stimulus” application at time zero. The graph displays three distinct temporal phases indicated by colored background regions. The “Latent period” (approximately 0-10 msec, shown with a yellow background) represents the brief delay between stimulus and visible contraction where tension remains at baseline. The “Contraction period” (approximately 10-30 msec, shown with a pink/salmon background) shows tension rising along a black curve from baseline to its peak. The “Relaxation period” (approximately 30-100 msec, shown with a light blue background) depicts tension gradually declining along the black curve back to baseline. The tension curve is smooth and bell-shaped, reaching maximum around 30 milliseconds before returning to baseline by 100 milliseconds. [Return to Figure 8.4.5]

Figure 8.4.6.This figure contains two graphs that illustrate different patterns of muscle contraction, both showing tension on the vertical axis and time on the horizontal axis. Graph (a), labeled “Wave summation,” displays a series of four individual muscle twitches occurring in relatively quick succession. The tension curve, shown in pink, rises and falls with each stimulus, creating a staircase-like pattern where each subsequent contraction begins before the previous one has fully relaxed. Below the tension curve, four individual stimulus spikes are shown as vertical lines, each corresponding to one contraction. The peaks increase progressively in height, demonstrating how tension accumulates when stimuli arrive before complete relaxation occurs. Graph (b), labeled “Tetanus,” shows the result of much more frequent stimulation. The tension curve rises rapidly and then maintains a sustained, elevated plateau for an extended period before declining. The area under the curve is filled with light pink, showing significantly greater total tension production compared to wave summation. Below this sustained contraction, approximately twenty closely-spaced stimulus spikes are shown, indicating rapid, repeated stimulation that prevents any relaxation between contractions. This high-frequency stimulation produces a smooth, fused contraction rather than the distinct individual twitches seen in wave summation. [Return to Figure 8.4.6]

Figure 8.4.7. This figure presents two side-by-side graphs illustrating different types of tetanic muscle contractions, both plotting tension on the vertical axis against time in milliseconds on the horizontal axis. The left graph, titled “Unfused (Incomplete) Tetanus,” shows a blue tension curve that exhibits a wavelike pattern with visible peaks and troughs. The curve progressively rises in a staircase fashion, with each successive peak reaching slightly higher than the previous one until approaching a horizontal dashed line labeled “Maximum Tension.” Small arrows marked “S” appear along the time axis at regular intervals, indicating the timing of each stimulus. The oscillating pattern demonstrates that the muscle experiences partial relaxation between stimuli, creating distinct though increasingly merged contractions. The right graph, titled “Fused (Complete) Tetanus,” displays a brown tension curve that rises steeply and then maintains a smooth, sustained plateau at the maximum tension level before dropping sharply during relaxation. Along the time axis, more frequent stimulus markers (S) are shown, approximately twice as many as in the unfused tetanus graph. The smooth plateau indicates that stimuli arrive so rapidly that individual twitches completely fuse together, eliminating any visible relaxation between contractions and producing maximal, sustained tension throughout the stimulation period. [Return to Figure 8.4.7]

Report an Error

Did you find an error, typo, broken link, or other problem in the text? Please follow this link to the error reporting form to submit an error report to the authors.